Archive for July, 2010

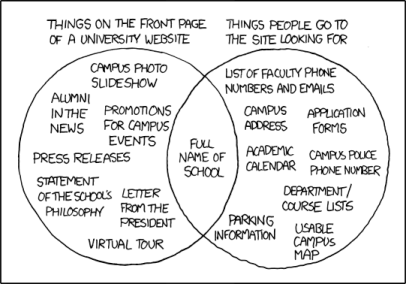

University Websites

| Peter Klein |

Add to: Facebook | Digg | Del.icio.us | Stumbleupon | Reddit | Blinklist | Twitter | Technorati

Rothbard Quote of the Day: Theory and History

| Peter Klein |

I stumbled recently upon this passage from Murray Rothbard’s review of Unemployment in History by the distinguished historian John A. Garraty. Rothbard’s review, published in 1978, raised an issue that has come up in previous discussions of the Freakonomics phenomenon (1, 2, 3, 4): Can a little theory, without accompanying real-world knowledge, be a dangerous thing?

I stumbled recently upon this passage from Murray Rothbard’s review of Unemployment in History by the distinguished historian John A. Garraty. Rothbard’s review, published in 1978, raised an issue that has come up in previous discussions of the Freakonomics phenomenon (1, 2, 3, 4): Can a little theory, without accompanying real-world knowledge, be a dangerous thing?

After chiding Garraty for writing about unemployment without knowing the basics of business-cycle theory, Rothbard adds:

My strictures against history which lacks any sound theoretical base are not meant to be an act of intellectual imperialism on behalf of economics and against history or other disciplines. Quite the contrary; the economist who ventures into the historical arena armed only with a few equations and mathematical razzle-dazzle has wreaked far more damage than the uninspired and slightly bumbling historian. For the economist, particularly the latter-day “cliometrician,” aims to flaunt his arrogant “scientific” pretensions of encompassing and explaining all of world history by means of a few mathematical symbols. The economist who knows no history understands far less than his opposite number in the historical profession; but his claims are far greater. Therefore, he is much wider off the mark.

Add to: Facebook | Digg | Del.icio.us | Stumbleupon | Reddit | Blinklist | Twitter | Technorati

Regulatory Capture

| Dick Langlois |

I seem to be on the “communitarianism” mailing list of Amitai Etzioni, missives from which are usually good for a cold frisson of annoyance. The most recent one seemed promising, however, as it touted a paper revisiting the capture theory of regulation. Many people have rightly criticized the Dodd-Frank Act for piling on unnecessary administrative regulation despite the fact that (A) regulation was already extensive and provided all the powers that would have been needed to avert the crisis and (B) much of the new regulation is aimed at activities that have nothing to do with the financial crisis. Etzioni points out that the potential for regulatory capture is an additional reason for concern. Quite so. Dependably, however, Etzioni comes to the wrong conclusion about the nature of the problem and how to fix it. To Etzioni, the problem is not the inherent liabilities of administrative regulation but the specter of private money corrupting the system. (Notably, his examples do not include the money of labor unions, which have captured, at the very least, vast swaths of the Labor and Education Departments.) As political speech is a topic on which I have already fulminated at some length, I will just add that, even in a world in which regulators were somehow insulated from financial temptation, there would still be capture: the operation of regulatory agencies depends on the possession of large amounts of specialized knowledge in whose generation the subjects of regulation have considerable, and oftentimes overwhelming, advantage.

Add to: Facebook | Digg | Del.icio.us | Stumbleupon | Reddit | Blinklist | Twitter | Technorati

Foss and Klein Critique of Kirzner

| Peter Klein |

The Spring 2010 issue of the Journal of Private Enterprise contains a Kirzner symposium, including a paper by Nicolai and me, “Alertness, Action, and the Antecedents of Entrepreneurship.” We critique Kirzner’s concept of the “pure entrepreneur,” arguing that alertness is a historically contingent attribute of real-world business people — what Mises calls “promoters” — but not essential to the entrepreneurial function itself. We also suggest that Kirzner is inconsistent on the issue of antecedents, simultaneously holding that the entrepreneur-as-discoverer exists outside any particular institutional environment, and that certain public policies inhibit entrepreneurial discovery by blocking profit opportunities. Some of the material in the paper is familiar to readers of our other works, but our critique of the Kirznerian pure entrepreneur, in the context of ideal types, goes beyond previous arguments.

Oh, some of you may be more interested in the rest of the special issue, which leads with Dan Klein and Jason Briggeman’s broadside, “Israel Kirzner on Coordination and Discovery,” followed by a lengthy response from Kirzner himself. (Our paper is really an addendum.) Pete Boettke and Dan D’Amico, Steve Horwitz, Gene Callahan, Bob Murphy, and Martin Ricketts round out the Kirzner symposium.

Add to: Facebook | Digg | Del.icio.us | Stumbleupon | Reddit | Blinklist | Twitter | Technorati

The Wikileaks Data Dump

| Peter Klein |

I’ve been fascinated by the reaction to the Wikileaks release of 90,000+ classified documents related Afghanistan war. US and British (and Pakistani) authorities are predictably outraged, while critics of the war are encouraged that the disclosures could help turn the tide, as did the Pentagon Papers three decades prior. What interests me the most, however, is the massive size of the Wikileaks archive. As the Guardian’s Roy Greenslade remarked, this is “data journalism.” Wikileaks doesn’t analyze, synthesize, attempt to corroborate, seek alternative points of view, write up the inverted-pyramid lead, or do the other things respectable journalists are supposed to do; it just dumps the data and lets others sort it out.

Some find this approach distasteful. A Pakistani official said “these reports betray a lack of understanding of the complexities of the nations involved.” Well, sure. They’re raw data, nothing more. But isn’t sharing data, and not just analysis, a quintessential New Economy phenomenon? Don’t we have search and analysis tools, data-mining algorithms, page rankings, and other means to sift through the huge piles of stuff that constitute the long tail? Shouldn’t expert commentary and analysis be replicable? Many journals now mandate data-sharing. E.g.: “It is the policy of the American Economic Review to publish papers only if the data used in the analysis are clearly and precisely documented and are readily available to any researcher for purposes of replication. Authors of accepted papers that contain empirical work, simulations, or experimental work must provide to the Review, prior to publication, the data, programs, and other details of the computations sufficient to permit replication. These will be posted on the AER Web site.” Why should foreign-affairs reporting be different?

Add to: Facebook | Digg | Del.icio.us | Stumbleupon | Reddit | Blinklist | Twitter | Technorati

Overconfidence

| Peter Klein |

Busenitz and Barney (1997) famously argued that entrepreneurs (founders) are particularly susceptible to overconfidence and representativeness biases. Compared to professional managers, entrepreneurs systematically overestimate the probability that a new venture will succeed and tend to draw unwarranted generalizations about the future from small samples. Overconfidence is now one of the major themes in the contemporary entrepreneurship literature (Bernardo and Welch, 2001; Forbes, 2005; Koellinger, Minniti, and Schade, 2007).

Busenitz and Barney (1997) famously argued that entrepreneurs (founders) are particularly susceptible to overconfidence and representativeness biases. Compared to professional managers, entrepreneurs systematically overestimate the probability that a new venture will succeed and tend to draw unwarranted generalizations about the future from small samples. Overconfidence is now one of the major themes in the contemporary entrepreneurship literature (Bernardo and Welch, 2001; Forbes, 2005; Koellinger, Minniti, and Schade, 2007).

A new NBER paper by Itzhak Ben-David, John Graham, and Campbell Harvey finds evidence for a particular kind of overconfidence, “miscalibration,” among corporate executives. Miscalibration occurs when the agent’s forecast probability distribution is too narrow, meaning that the likelihood of extremely positive or negative events is unrealistically discounted. The idea is that agents with miscalibrated expectations are overconfident, not in the success of their activities (what the authors label “optimism”), but in their ability to predict the success of their activities. Survey evidence from a sample of CFOs reveals a number of interesting regularities about the relationship between miscalibration and past financial performance, corporate investment, and other observables. Here’s the abstract:

Miscalibration is a form of overconfidence examined in both psychology and economics. Although it is often analyzed in lab experiments, there is scant evidence about the effects of miscalibration in practice. We test whether top corporate executives are miscalibrated, and study the determinants of their miscalibration. We study a unique panel of over 11,600 probability distributions provided by top financial executives and spanning nearly a decade of stock market expectations. Our results show that financial executives are severely miscalibrated: realized market returns are within the executives’ 80% confidence intervals only 33% of the time. We show that miscalibration improves following poor market performance periods because forecasters extrapolate past returns when forming their lower forecast bound (“worst case scenario”), while they do not update the upper bound (“best case scenario”) as much. Finally, we link stock market miscalibration to miscalibration about own-firm project forecasts and increased corporate investment.

I’m not aware of any entrepreneurship studies that distinguish miscalibration from optimism, in the sense those terms are used here. Am I missing something?

Add to: Facebook | Digg | Del.icio.us | Stumbleupon | Reddit | Blinklist | Twitter | Technorati>

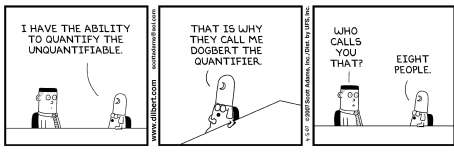

Performance Evaluation Links

| Peter Klein |

Performance evaluation is a favorite topic here at O&M; readers may enjoy these miscellaneous items on measurement:

- “Is Impact Measurement a Dead End?” by Alanna Shaikh, guest blogging at AidWatch.

- Moneyball’s Michael Lewis on basketball player statistics (HT: PB).

- The Urban Institute’s Outcome Indicators Project for nonprofits.

- Relevant Demotivators: Flattery, Ineptitude, and Mediocrity.

Add to: Facebook | Digg | Del.icio.us | Stumbleupon | Reddit | Blinklist | Twitter | Technorati

Summary of Dodd-Frank Act

| Peter Klein |

The Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act — I’ll refrain from snarks about the title — was signed into law today by President Obama. Here is a very useful summary by William Sweet of the Act’s contents and likely consequences. In a nutshell: “The Dodd-Frank Act effects a profound increase in regulation of the financial services industry. The Act gives U.S. governmental authorities more funding, more information and more power. In broad and significant areas, the Act endows regulators with wholly discretionary authority to write and interpret new rules.” Aren’t you shocked that it passed?

Update: Larry Ribstein is not happy. Weil Gotshal provides further details.

Add to: Facebook | Digg | Del.icio.us | Stumbleupon | Reddit | Blinklist | Twitter | Technorati

The Organizational Economics of the BP Oil Spill

Now that passions are cooling regarding the BP disaster, it’s time to bring organizational issues into the discussion.

1. Everyone knows about the liability caps and the role they may have played in encouraging moral hazard. Just as bank deposits are guaranteed by government deposit insurance, and large banks themselves are probably Too Big to Fail, liability for property damage from oil spills off US waters is limited to $75 million (plus cleanup costs), based on a 1990 law passed after the Exxon Valdiz spill. This presumably mitigates drillers’ incentives to manage environmental risk. Indeed, oil companies enjoy a very cozy relationship with their ostensible guardians; as the NY Times noted, “[d]ecades of law and custom have joined government and the oil industry in the pursuit of petroleum and profit.” The federal agency that oversees drilling, the Minerals Management Service, rakes $13 billion a year in fees in what amounts to a public-private partnership. And does anyone really think the British government would “stand idly by” if BP’s status as an ongoing concern were threatened by criminal or civil penalties?

2. As Bill Shughart points out, BP did not own the Deepwater Horizon platform, but leased it from a company called Transocean. To Bill this suggests “a classic principal-agent problem in which the duties and responsibilities of lessor and lessee undoubtedly were not spelled out fully, especially with respect to maintenance and testing of the rig’s blowout preventer as well as to the advisability of installing a second ‘blind sheer ram,’ which may have been able to plug the well after the first (and only one then in service) failed to do so.” Would BP have paid more attention to safety if it owned, rather than leased, the platform? (more…)

Misc Academic Links

| Peter Klein |

- Academia’s love-hate relationship with wikis.

- Deathbed witticisms from Voltaire, Hegel, and other interesting persons.

- Should research universities exploit the internal division of labor?

- Tips on academic job talks from Fabio’s valuable series.

Add to: Facebook | Digg | Del.icio.us | Stumbleupon | Reddit | Blinklist | Twitter | Technorati

Political and Methodological Individualism

| Peter Klein |

Further to Nicolai’s post, it is also widely believed that methodological individualism — the chief explanatory principle of economics and rational-choice sociology and political science — implies or justifies political individualism or, even worse, some kind of metaphysical or ontological individualism. “But people are social beings!” cry the critics. Well, sure. Methodological individualism is simply the view that social phenomena should be explained, or understood, in terms of the values, beliefs, plans, and actions of the individual that make up the social whole. It makes no claims about the ultimate source of these values and beliefs, the degree to which people are influenced by society, etc. It is a principle of explanation, nothing more.

Further to Nicolai’s post, it is also widely believed that methodological individualism — the chief explanatory principle of economics and rational-choice sociology and political science — implies or justifies political individualism or, even worse, some kind of metaphysical or ontological individualism. “But people are social beings!” cry the critics. Well, sure. Methodological individualism is simply the view that social phenomena should be explained, or understood, in terms of the values, beliefs, plans, and actions of the individual that make up the social whole. It makes no claims about the ultimate source of these values and beliefs, the degree to which people are influenced by society, etc. It is a principle of explanation, nothing more.

Here’s a plain statement from Schumpeter, the guy who coined the term “methodological individualism” (okay, he used methodische Individualismus, and borrowed the concept from Weber), writing in 1908:

[W]e must strictly differentiate between political and methodological individualism, as the two have virtually nothing in common. the former starts form the general assumption that freedom, more than anything, contributes to the development of the individual and the well-being of society as a whole and puts forward a number of practical propositions in support of this. The latter is quite different. It has no specific propositions and no prerequisites, it just means that it bases certain economic processes on the actions of individuals. Therefore the question really is: is it practical to use the individual as a basis and would there be enough scope in doing so, or would it be better, in view of specific problems and the national economy as a whole, to use society as a basis. This question is purely methodological and involves no important principle. The socialists can answer it in terms of methodological individualism and the political individualists in terms of their social concept of things, without getting into conflict with their convictions.

See also the Mises quotes discussed here.

Add to: Facebook | Digg | Del.icio.us | Stumbleupon | Reddit | Blinklist | Twitter | Technorati

“De Gustibus Non Est Disputandum”?

| Nicolai Foss |

History of econ nerds (wonks?) will know that John Stuart Mill was trained by his father (James Mill) from the age of three in the Greek and Latin languages. Since Mill, economists’ Latin capabilities have deteriorated rather badly (a result of the dominance of Greek notation? ;-)). In fact, most economists only know two Latin sentences (or rather, dicta) that, however, they love to blurt out, often with a smug smile. One is a sound analytical principle, namely the ceteris paribus principle. The other is a much more problematic (if applied outside of economics) claim, made famous to economists by George Stigler and Gary Becker, namely “de gustibus non est disputandum.”

I have always been surprised by the readiness of many economists to endorse this claim as a general claim that goes beyond the simple implication that in economics we take preferences as given and applies on the aesthetic domain (perhaps this simply reflects the fact that many people nowadays subscribe to total or near-total relativism in aesthetics). However, understood as an aesthetic claim, “de gustibus non est disputandum” lies entirely outside of the orbit of economics (and economists-as-economists should shut up), and is emphatically not implied by subjective value theory, or any related branch of subjectivism in economics. (more…)

Miscellaneous Organizational Links

| Peter Klein |

- The much-anticipated KKR IPO turned out to be a snoozer. But what the heck is a publicly traded private-equity firm anyway?

- Is the flattening hierarchy an illusion, driven by job-title inflation?

- How call centers use behavioral economics.

- Belén Villalonga’s new paper on ownership concentration and internal-capital-market efficiency — highly recommended.

Add to: Facebook | Digg | Del.icio.us | Stumbleupon | Reddit | Blinklist | Twitter | Technorati

Mises Quote of the Day

| Peter Klein |

From Human Action, chapter 15, section 11 (via JGL):

In order to succeed in business a man does not need a degree from a school of business administration. These schools train the subalterns for routine jobs. They certainly do not train entrepreneurs. An entrepreneur cannot be trained. A man becomes an entrepreneur in seizing an opportunity and filling the gap. No special education is required for such a display of keen judgment, foresight, and energy. The most successful businessmen were often uneducated when measured by the scholastic standards of the teaching profession. But they were equal to their social function of adjusting production to the most urgent demand. Because of these merits the consumers chose them for business leadership.

Add to: Facebook | Digg | Del.icio.us | Stumbleupon | Reddit | Blinklist | Twitter | Technorati

Incentives Matter, Soviet Edition

| Dick Langlois |

As economists like Benito Arruñada and Eric Hilt have shown, fishing and whaling have always used an incentive system in which crew members are paid a share of the profits of the voyage. Recall that Ishmael in Moby Dick contracted for a 300th lay, a 300th “part of the clear nett proceeds of the voyage, whatever that might eventually amount to.” This provides relatively high-powered incentives, in that it is a reward based on results, though it works only when team members can monitor each other easily and when the market for workers is competitive. (This contrasts with the reward system in, say, professional sports, where one is rewarded on the basis of one’s own performance rather than on that of the team. But that may be changing.)

As economists like Benito Arruñada and Eric Hilt have shown, fishing and whaling have always used an incentive system in which crew members are paid a share of the profits of the voyage. Recall that Ishmael in Moby Dick contracted for a 300th lay, a 300th “part of the clear nett proceeds of the voyage, whatever that might eventually amount to.” This provides relatively high-powered incentives, in that it is a reward based on results, though it works only when team members can monitor each other easily and when the market for workers is competitive. (This contrasts with the reward system in, say, professional sports, where one is rewarded on the basis of one’s own performance rather than on that of the team. But that may be changing.)

I was surprised to discover that even Soviet factory ships used a similar system, as described in the Martin Cruz Smith novel Polar Star — a work of fiction but clearly well researched and probably accurate. “The Polar Star’s pay was shared on a coefficient from 2.55 shares for the captain to 0.8 share for a secondclass seaman. Then there was a polar coefficient of 1.5 for fishing in Arctic seas, a 10 percent bonus for one year’s service, a 10 percent bonus for meeting the ship’s quota, and a bonus as high as 40 percent for overfulfilling the plan. The quota was everything. It could be raised or lowered after the ship left dock, but was usually raised because the fleet manager drew his bonus from saving on seamen’s wages. Transit time to the fishing grounds was set at so many days, and the whole crew lost money when the captain ran into a storm, which was why Soviet ships sometimes went full steam ahead through fog and heavy seas.”

Presumably, however, the share was not of profit but of some fixed amount. The incentive came from the quota bonuses, which, as the novel details, were subject to political manipulation. Interesting nonetheless that the system used incentives of the broadly traditional kind, and that it explicitly rewarded workers differently for different skill level and status.

Add to: Facebook | Digg | Del.icio.us | Stumbleupon | Reddit | Blinklist | Twitter | Technorati

Hayek Interviews

| Peter Klein |

In 1983 the Earhart Foundation sponsored a lengthy set of interviews with F. A. Hayek in Los Angeles. The transcripts have long been available (and form the basis of the interview parts of Hayek on Hayek), but the complete set of videos has just now been put online, courtesy of the Universidad Francisco Marroquín. The interviewers are an impressive lot as well: James Buchanan, Armen Alchian, Axel Leijonhufvud, Robert Bork, Tom Hazlett, Jack High, Bob Chitester, Leo Rosten, and Earlene Craver. (I hardly recognized the youthful Hazlett!) You can also get the transcripts, if you prefer plain text.

In 1983 the Earhart Foundation sponsored a lengthy set of interviews with F. A. Hayek in Los Angeles. The transcripts have long been available (and form the basis of the interview parts of Hayek on Hayek), but the complete set of videos has just now been put online, courtesy of the Universidad Francisco Marroquín. The interviewers are an impressive lot as well: James Buchanan, Armen Alchian, Axel Leijonhufvud, Robert Bork, Tom Hazlett, Jack High, Bob Chitester, Leo Rosten, and Earlene Craver. (I hardly recognized the youthful Hazlett!) You can also get the transcripts, if you prefer plain text.

Add to: Facebook | Digg | Del.icio.us | Stumbleupon | Reddit | Blinklist | Twitter | Technorati

Incentives Matter, Little Big Horn Edition

| Peter Klein |

Thanks to Norman Van Cott for this tidbit, which I hadn’t known before:

The crux of Roger McGrath’s review of Nathaniel Philbrick’s “The Last Stand” (Bookshelf, June 18) is that George Custer’s “undoing was the wildly inaccurate information he [Custer] received about the number of Indian warriors he might face.” Left unnoted by Mr. McGrath is the role perverse public-sector economic incentives played in generating this information.

To wit, Indian reservation agents’ salaries varied directly with reservation populations. More Indians, more money. This provided agents an incentive to inflate reservation population counts, which led in turn to underestimates of the number of Indians on the warpath. For the economist, the Little Bighorn debacle is an excellent example of public choice economics in action.

Details about how these incentives affected the population counts appear in a previous decade’s classic study of Custer, Evan Connell’s 1984 “Son of the Morning Star.” For example, prior to the battle, agents reported 37,391 Indians on the reservations. A U.S. Army count after the battle turned up 11,660. That Custer’s soldiers ended up facing perhaps twice as many Indians as they had been told to expect is not surprising. Incentives matter.

Add to: Facebook | Digg | Del.icio.us | Stumbleupon | Reddit | Blinklist | Twitter | Technorati

Tesla (the Car)

| Dick Langlois |

Speaking of Tesla: as I was waiting to cross Page Mill Road in Palo Alto the other day, I saw a real live Tesla drive by — the car, not the long-dead inventor. There are several dealerships along El Camino.

Speaking of Tesla: as I was waiting to cross Page Mill Road in Palo Alto the other day, I saw a real live Tesla drive by — the car, not the long-dead inventor. There are several dealerships along El Camino.

In their recent comment, Mari Sako and Susan Helper suggested that electric vehicles might be an example in which, because of the systemic nature of innovation, we might see considerable vertical integration à la Chandler. They talked about the complementary network of charging stations, etc. But it seems to me that what vertical integration the electric vehicle will bring about is more likely to be in the design and production of the car itself. For example, the Tesla website notes that the “Roadster is controlled by state-of-the-art vehicle software. Rooted in Silicon Valley tradition, the code is developed in-house with an intense focus on agile and constant innovation.” Presumably they mean that the code itself, not the vertical integration, is rooted in Silicon Valley tradition.

Apparently, Tesla (along with Toyota) is going to reopen the famed NUMMI plant in Fremont to make its new passenger-car model.

Add to: Facebook | Digg | Del.icio.us | Stumbleupon | Reddit | Blinklist | Twitter | Technorati

The History of Nikola Tesla

| Peter Klein |

Saturday was Nikola Tesla’s birthday. Here’s Jeremiah Warren’s video in Tesla’s honor:

Tesla was, of course, the great inventor whose technical achievements outshone those of his great rival, Thomas Edison, but who was unable to commercialize any of his discoveries. Tesla, unfortunately, put his faith in intellectual property-rights protection, while Edison emphasized management and marketing. As Danny Quah puts it, “Public relations and entrepreneurial savvy trump the raw intellectual idea.”

Add to: Facebook | Digg | Del.icio.us | Stumbleupon | Reddit | Blinklist | Twitter | Technorati

Stanford Conference on the Asian Firm

| Dick Langlois |

I’m in Palo Alto, having just participated in an extremely interesting conference at Stanford called “The Future of Industry and Innovation in Asia: Firms, Alliances and Networks.” (Papers are not on the website, but you can email the authors.) The conference was organized by Mark Fruin and Raffiq Dossani, and featured people like Martin Kenney, Masao Nakamura, Tim Sturgeon, and Eleanor Westney.

Add to: Facebook | Digg | Del.icio.us | Stumbleupon | Reddit | Blinklist | Twitter | Technorati

Recent Comments