Posts filed under ‘Management Theory’

Measuring Tacit Knowledge

| Peter Klein |

| Peter Klein |

The concept of tacit knowledge — knowledge that is difficult or impossible to parameterize, or to express in words or numbers — is central to organization theory, as well as philosophy (Polanyi) and social theory more generally (Hayek). Most of the research literature on tacit knowledge is conceptual and theoretical, such as Hayek’s famous “Use of Knowledge in Society” (1945) or more recent pieces like Jensen and Meckling’s “Specific and General Knowledge, and Organizational Structure” (1992). Empirical studies of tacit knowledge are rare, which is not surprising given the idiosyncratic, personal, subjective, and often ephemeral nature of such knowledge.

An interesting new NBER paper by David Chan estimates the effects of tacit knowledge using matched pairs of physician trainees with similar levels of explicit knowledge but different levels of experience and hence accumulated know-how. The hospital setting allows for some clever tricks, e.g., exogenous sorting into occupational roles by experience, rather than ability. Measuring outcomes via spending is problematic to me, though standard in the medical economics and management literatures. Check it out:

Uncertainty, Tacit Knowledge, and Practice Variation: Evidence from Physicians in Training

David C. Chan, Jr

NBER Working Paper No. 21855, January 2016Studying physicians in training, I investigate how uncertainty and tacit knowledge may give rise to significant practice variation. Consistent with tacit knowledge accruing only with experience, and empirically exploiting a discontinuity in the formation of teams, experience relative to a peer substantially increases the size of variation attributable to the physician trainees. Among the same physician trainees, convergence occurs for patients on services driven by specialists, where there is arguably more explicit knowledge, but not on the general medicine service. This difference is unexplained by formally coded patient information. In contrast, rich physician characteristics correlated with preferences and ability, and quasi-random assignments to high- or low-spending supervising physicians explain little if any variation.

SMACK-down of Evidence-Based Medicine

| Peter Klein |

As a skeptic of the evidence-based management movement (championed by Pfeffer, Sutton, et al.) I was amused by a recent spoof article in the Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, “Maternal Kisses Are Not Effective in Alleviating Minor Childhood Injuries (Boo-Boos): A Randomized, Controlled, and Blinded Study,” authored by the Study of Maternal and Child Kissing (SMACK) Working Group. Maternal kisses were associated with a positive and statistically significant increase in the Toddler Discomfort Index (TDI):

As a skeptic of the evidence-based management movement (championed by Pfeffer, Sutton, et al.) I was amused by a recent spoof article in the Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, “Maternal Kisses Are Not Effective in Alleviating Minor Childhood Injuries (Boo-Boos): A Randomized, Controlled, and Blinded Study,” authored by the Study of Maternal and Child Kissing (SMACK) Working Group. Maternal kisses were associated with a positive and statistically significant increase in the Toddler Discomfort Index (TDI):

Maternal kissing of boo-boos confers no benefit on children with minor traumatic injuries compared to both no intervention and sham kissing. In fact, children in the maternal kissing group were significantly more distressed at 5 minutes than were children in the no intervention group. The practice of maternal kissing of boo-boos is not supported by the evidence and we recommend a moratorium on the practice.

The actual author, Mark Tonelli, is a prominent critic of evidence-based medicine, described by the journal’s editor as a “collapsing” movement and in a recent British Journal of Medicine editorial as a “movement in crisis.” Most of the criticisms of evidence-based medicine will sound familiar to Austrian economists: overreliance on statistically significant, but clinically irrelevant, findings in large samples; failure to appreciate context and interpretation; lack of attention to underlying mechanisms rather than unexplained correlations; and a general disdain for tacit knowledge and understanding.

My guess is that evidence-based management, which is modeled after evidence-based medicine, is in for a similarly rocky ride. Teppo had some interesting orgtheory posts on this a few years ago (e.g., here and here). Evidence-based management has been criticized, as you might expect, by critical theorists and other postmodernists who don’t like the concept of “evidence” per se but the real problems are more mundane: what counts as evidence, and what conclusions can legitimately be drawn from this evidence, are far from obvious in most cases. Particularly in entrepreneurial settings, as we’ve written often on these pages, intuition, Verstehen, or judgment may be more reliable guides than quantitative, analytical reasoning.

Update: Thanks to Ivan Zupic for pointing me to a review and critique of EBM in the current issue of AMLE.

I Agree with Larry Summers

| Peter Klein |

Justin Fox reports on a recent high-powered behavioral economics conference featuring Raj Chetty, David Laibson, Antoinette Schoar, Maya Shankar, and other important contributors to this growing research stream. But he refers also to the “Summers critique,” the idea that key findings in behavioral economics research sound like recycled wisdom from business practitioners.

Summers [in 2012] told a story about a college acquaintance who as a cruel prank signed up another classmate for 60 different subscriptions of the Book-of-the-Month-Club ilk. The way these clubs worked is that once you signed up, you got a book in the mail every month and were charged for it unless you (a) sent the book back within a certain period of time or (b) went through the hassle of extricating yourself from the club altogether. Customers had to opt out in order to not keep buying books, so they bought more books than they otherwise would have. Book marketers, Summers said, had figured out the power of defaults long before economists had.

More generally, Fox asks, “Have behavioral economists really discovered anything new, or have they simply replaced some wrong-headed notions of post-World War II economics with insights that people in business have understood for decades and maybe even centuries?”

I took exactly the Summers line in a 2010 post, observing that behavioral economics “often seems to restate common, obvious, well-known ideas as if they are really novel insights (e.g., that preferences aren’t stable and predictable over time). More novel propositions are questionable at best.” I used a Dan Ariely column on compensation policy as an example:

He claims as a unique insight of behavioral economics that when people are evaluated according to quantitative measures of performance, they tend to focus on the measures, not the underlying behavior being measured. Well, duh. This is pretty much a staple of introductory lectures on agency theory (and features prominently in Steve Kerr’s classic 1975 article). Ariely goes on to suggest that CEOs should be rewarded not on the basis of a single measure of performance, but multiple measures. Double-duh. Holmström (1979) called this the “informativeness principle” and it’s in all the standard textbooks on contract design and compensation structure (e.g., Milgrom and Roberts, Brickley et al., etc.) (Of course, agency theory also recognizes that gathering information is costly, and that additional metrics are valuable, on the margin, only if the benefits exceed the costs, a point unmentioned by Ariely.)

Maybe Larry and I should hang out.

Foss Wins Best Article Award

| Peter Klein |

Nicolai is far too modest to mention it (and no, he did not make me do this), but he has won Sloan Management Review’s best article prize:

The editors of MIT Sloan Management Review are pleased to announce the winners of this year’s Richard Beckhard Memorial Prize, awarded to the authors of the most outstanding MIT SMR article on planned change and organizational development published between fall 2013 and summer 2014.

This year’s Richard Beckhard Memorial Prize goes to the spring 2014 MIT SMR article by Julian Birkinshaw, Nicolai J. Foss, and Siegwart Lindenberg, entitled “Combining Purpose With Profits.”

In this article, the authors examine a familiar and important question for managers: How can the tension between purpose and profits be best managed? The authors explore the kinds of structures companies need to put in place to provide clarity and direction for employees while also serving to both motivate individuals and draw people together in a common pursuit.

As the judges for the prize pointed out, the tension between purpose and profit is well-known, and many companies claiming to have “pro-social goals” have difficulty backing up their claims. However, the judges were impressed with the examples the authors presented of companies that have actually been able to balance purpose and profit. Some were familiar (such as Whole Foods Market and Tata Group), but others were less so (such as the Swedish bank Svenska Handelsbanken and HCL Technologies, an India-based IT-services company).

The pro-social goals the companies emphasize — for example, putting employees first or investing in local communities — are hardly elaborate or surprising. What is important is that companies put systems in place to meet these goals. For instance, at Tata, where the pro-social goal is “to improve the quality of life in the communities we serve,” the supporting systems include charitable trusts that own the majority of the equity capital of the Tata Sons holding company. Pro-social goals require what the authors call a “counterweight,” such as an employee council or a measuring system, to ensure that the pro-social goals continue to have influence.

The judges thought the article was well aligned with the beliefs of Richard Beckhard, who insisted that what truly motivates employees is the sense that what they do matters and serves a purpose that goes beyond organizational profitability or personal gain. As the judges observed, “What engages people is the broader, value-centered question of why we do what we do — precisely what the three authors of this year’s winning article make evident.”

This year’s panel of judges consisted of distinguished members of the MIT Sloan School faculty: Schussel Family Professor and chairman of the MIT Sloan Management Review managing board Erik Brynjolfsson, retired senior lecturer Cyrus Gibson, and Erwin H. Schell Professor of Management John Van Maanen.

Nicolai, you can do great things, when you pick the right coauthors….

Piece Rates and Multitasking

| Peter Klein |

A canonical result of multitask agency theory is that, when agents are assigned to multiple activities and some are more easily measured than others, piece-rate incentive schemes encourage agents to focus on the measurable activities while shirking the others. Professors at research universities, for example tend to focus on research at the expense of teaching — not because they don’t care about teaching, but because research output is easy to measure, while teaching quality isn’t, so administrators wishing to reward good performance tend to base their evaluations on research productivity. Or so I’ve heard (ahem). The implication is that, to encourage balanced effort and performance across activities, supervisors should rely at least partly on subjective, holistic evaluation criteria, and not just objective, quantitative measures of employee performance, or even do away with incentive compensation altogether.

A canonical result of multitask agency theory is that, when agents are assigned to multiple activities and some are more easily measured than others, piece-rate incentive schemes encourage agents to focus on the measurable activities while shirking the others. Professors at research universities, for example tend to focus on research at the expense of teaching — not because they don’t care about teaching, but because research output is easy to measure, while teaching quality isn’t, so administrators wishing to reward good performance tend to base their evaluations on research productivity. Or so I’ve heard (ahem). The implication is that, to encourage balanced effort and performance across activities, supervisors should rely at least partly on subjective, holistic evaluation criteria, and not just objective, quantitative measures of employee performance, or even do away with incentive compensation altogether.

An interesting paper in the January 2015 Southern Economic Journal offers a different theory, and some experimental evidence to back it up, suggesting that piece rates may actually be better than other schemes under multitasking. The idea is that agents may be uncertain about the principal’s monitoring ability, and the choice of a piece-rate scheme signals that the principal is a good monitor. This signaling effect can, under certain conditions, overcome the standard distortionary effect described above. Put differently, relying on subjective, holistic evaluation criteria, or abandoning performance measurement altogether (Alfie Kohn cheers!), may signal a sophisticated, experienced principal, but may also signal a principal who is too lazy to pay attention to employee behavior at all.

The paper is by Omar Al-Ubaydli, Steffen Andersen, Uri Gneezy, and John List and is cleverly titled “Carrots That Look Like Sticks: Toward an Understanding of Multitasking Incentive Schemes.” (Yes, it is part of the List Project on which we have mixed opinions.) Here is more on multitasking.

Casson on Methodological Individualism

| Peter Klein |

Thanks to Andrew for the pointer to this weekend’s Reading-UNCTAD International Business Conference featuring Mark Casson, Tim Devinney, Marcus Larsen, and many others. Mark’s talk (not yet online) focused on the need for methodological individualism in international business research. “Firms don’t take decisions, individuals do. When you say that a firm pursued an international strategy, you really mean that that the CEO persuaded the individuals on the board to go along with his or her strategy.” As Andrew summarizes:

Thanks to Andrew for the pointer to this weekend’s Reading-UNCTAD International Business Conference featuring Mark Casson, Tim Devinney, Marcus Larsen, and many others. Mark’s talk (not yet online) focused on the need for methodological individualism in international business research. “Firms don’t take decisions, individuals do. When you say that a firm pursued an international strategy, you really mean that that the CEO persuaded the individuals on the board to go along with his or her strategy.” As Andrew summarizes:

Casson spoke at great length about the need for research that focuses on named individuals, is based on the extensive study of primary sources in archives, takes social and political context into account, and which looks at case studies of entrepreneurs in different time periods. In effect, he was calling for the re-integration of Business History into International Business research.

And a renewed emphasis on entrepreneurship, not as a standalone subject dealing with startups or self-employment, but as central to the study of organizations — a theme heartily endorsed on this blog.

Review of Organizing Entrepreneurial Judgment

| Peter Klein |

David Howden’s generous review of Organizing Entrepreneurial Judgment appears in the March 2015 issue of the International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal. Excerpt:

David Howden’s generous review of Organizing Entrepreneurial Judgment appears in the March 2015 issue of the International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal. Excerpt:

This ambitious book has a three-fold purpose. First, it seeks to clarify “entrepreneurship” in a manner amenable to both modern management and economics literature. Second, it redefines the theory of the firm in order to integrate the role of the entrepreneur more fully and give a comprehensive view on why firms exist. Finally, and most successfully, it sheds light on the internal organization of the firm, and how entrepreneurship theory can augment our understanding of why firms adopt the hierarchies they do. . . .

Organizing Entrepreneurial Judgment is a massive undertaking, and one that ambitiously spans the unnecessary divide between management studies and economics literature. For the scholar seriously contemplating exploiting this gap further, the book is highly recommended. Having thoroughly enjoyed reading this rendition of their entrepreneurial theory of the firm, it is this reviewer’s hope that Foss and Klein continue to carve out this growing niche straddling the two disciplines. Following up with a more direct and focused primer on their firm would be a welcome contribution to further the growing field.

Also, at last November’s SDAE conference, the book received the 2014 FEE Prize for best book in Austrian economics.

We have several new papers coming out that develop, extend, and defend the judgment-based perspective. Details to follow.

Two Large-Sample Empirical Papers on Strategy and Organization

| Peter Klein |

Bryan Hong, Lorenz Kueng, and Mu-Jeung Yang have two new NBER papers on strategy and organization using a seven-year panel of about 5,500 Canadian firms. The papers exploit the Workplace and Employee Survey administered annually by Statistics Canada. The data, the authors’ approach, and the results should be very interesting to O&M readers. Here are the links to the NBER versions; there may be ungated versions as well.

Business Strategy and the Management of Firms

NBER Working Paper No. 20846, January 2015Business strategy can be defined as a firm’s plan to generate economic profits based on lower cost, better quality, or new products. The analysis of business strategy is thus at the intersection of market competition and a firm’s efforts to secure persistently superior performance via investments in better management and organization. We empirically analyze the interaction of firms’ business strategies and their managerial practices using a unique, detailed dataset on business strategy, internal firm organization, performance and innovation, which is representative of the entire Canadian economy. Our empirical results show that measures of business strategy are strongly correlated with firm performance, both in the cross-section and over time, and even after controlling for unobserved profit shocks exploiting intermediates utilization. Results are particularly striking for innovation, as firms with some priority in business strategies are significantly more likely to innovate than firms without any strategic priority. Furthermore, our analysis highlights that the relationship between strategy and management is driven by two key organizational trade-offs: employee initiative vs. coordination as well as exploration of novel business opportunities vs. exploitation of existing profit sources.

Estimating Management Practice Complementarity between Decentralization and Performance Pay

NBER Working Paper No. 20845, January 2015The existence of complementarity across management practices has been proposed as one potential explanation for the persistence of firm-level productivity differences. However, thus far no conclusive population-level tests of the complementary joint adoption of management practices have been conducted. Using unique detailed data on internal organization, occupational composition, and firm performance for a nationally representative sample of firms in the Canadian economy, we exploit regional variation in income tax progression as an instrument for the adoption of performance pay. We find systematic evidence for the complementarity of performance pay and decentralization of decision-making from principals to employees. Furthermore, in response to the adoption of performance pay, we find a concentration of decision-making at the level of managerial employees, as opposed to a general movement towards more decentralization throughout the organization. Finally, we find that adoption of performance pay is related to other types of organizational restructuring, such as greater use of outsourcing, Total Quality Management, re-engineering, and a reduction in the number of layers in the hierarchy.

More on Strategy and Game Theory

| Peter Klein |

Recent posts on strategy and game theory (here and here) generated quite a lot of discussion here and on social media. Avinash Dixit offers more grist for the mill in his December 2014 Journal of Economic Literature essay on Lawrence Freedman’s Strategy: A History (Oxford, 2013). (An ungated version is here.) Dixit’s essay contrasts the economist’s and the historian’s view of strategy — “strategy” being game theory for the former, a broader, interpretive, interdisciplinary exercise for the latter — but the discussion is highly relevant for strategic management. The management literature has traditionally taken a wide, flexible view of “strategy,” closer to the historian’s sense than the economist’s, though that is rapidly changing as game theory becomes more widespread in strategic management research and teaching.

Recent posts on strategy and game theory (here and here) generated quite a lot of discussion here and on social media. Avinash Dixit offers more grist for the mill in his December 2014 Journal of Economic Literature essay on Lawrence Freedman’s Strategy: A History (Oxford, 2013). (An ungated version is here.) Dixit’s essay contrasts the economist’s and the historian’s view of strategy — “strategy” being game theory for the former, a broader, interpretive, interdisciplinary exercise for the latter — but the discussion is highly relevant for strategic management. The management literature has traditionally taken a wide, flexible view of “strategy,” closer to the historian’s sense than the economist’s, though that is rapidly changing as game theory becomes more widespread in strategic management research and teaching.

Here’s an excerpt from Dixit’s opening, which gives you the flavor:

[Freedman] heads the preface with a memorable quote from Mike Tyson: “Everyone has a plan till they get punched in the mouth.” Later he quotes another fighter, the legendary German Field Marshal Helmuth Karl Bernhard Graf von Moltke: “no plan survived contact with the enemy” (p. 104). The game theorist will respond: “Those plans are not strategies. They are incomplete. They fail to specify any action at the node of the game tree where you get punched in the mouth or meet the enemy army, or in the ensuing subgame.” It would be extreme stupidity, or arrogance tantamount to stupidity, for a boxer not to recognize the possibility of getting punched in the mouth. And although avoiding battle may be an important aspect of military strategy in many situations (see pp. 47–9), every plan should include a provision for action if or when battle commences. Tyson, or Freedman, will probably counter that even if the boxer starts with a complete plan that specifies the action for this contingency, the punch will make him forget the plan and react hot-headedly. Modern game theorists exposed to behavioral ideas will admit some truth in this, and agree that the boxer’s System 2 calculations are likely to fly out of the ring when the punch lands and System 1 instincts will take over. But they will add that that makes it all the more important for the boxer to strategize better in advance—to take actions before getting punched, either to reduce the risk, or to arrange matters in such a way that the anger and instinct (or the prospects of such reactions) are put to more effective use, as with the strategy of brinkmanship. More generally, “the art of creating power” often entails strategic moves like commitments, threats and promises that game theorists have analyzed following Thomas Schelling (1960). And Freedman’s picture of “strategy as a System 2 process engaged in a tussle with System 1 thinking” (p. 605) looks remarkably like Schelling’s (1984, ch. 3) “intimate contest for self-command.”

I have a twofold purpose in constructing the above exchange. One is to highlight the difference between the perspectives of economists and historians in thinking about the same situation. The second is to argue that each has something to learn from the other, and a fuller understanding can result from their dialog. The two perspectives share a lot of middle ground, and have useful complementarities.

The thoughtful essay is well worth reading in its entirety.

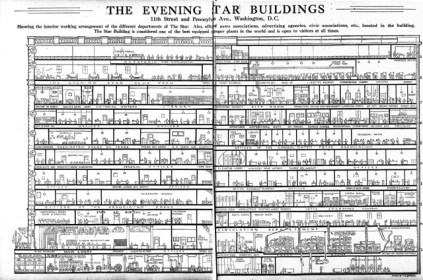

An Information Flow Diagram from 1922

| Peter Klein |

We’ve featured some cool vintage diagrams before, such as the New York and Erie Railroad organizational chart and the diagrams of the Mundaneum. Here’s an information flow diagram from 1922, represented as a cutaway view of the Washington Star newspaper offices. As Jason Kottke notes, it provides “a fascinating view of how information flowed through a newspaper company in the 1920s. Raw materials in the form of electricity, water, telegraph messages, paper, and employees enter the building and finished newspapers leave out the back.”

PhD Strategy Syllabi

| Peter Klein |

Russ Coff has assembled an impressive list of syllabi and reading lists for PhD courses in strategy, innovation, research methods, and related subjects. Feel free to send him additional suggestions. Many useful references here for faculty and students teaching or taking these courses, and for anybody wishing to learn more about classic and contemporary literature in strategic management research.

Two Interesting NBER Papers

| Peter Klein |

A couple of recent NBER papers of interest to O&Mers, one from Doug Irwin, another from Luis Garicano and Esteban Rossi-Hansberg:

Adam Smith’s “Tolerable Administration of Justice” and the Wealth of Nations

Douglas A. Irwin

NBER Working Paper No. 20636, October 2014In the Wealth of Nations, Adam Smith argues that a country’s national income depends on its labor productivity, which in turn hinges on the division of labor. But why are some countries able to take advantage of the division of labor and become rich, while others fail to do so and remain poor? Smith’s answer, in an important but neglected theme of his work, is the security of property rights that enable individuals to “secure the fruits of their own labor” and allow the division of labor to occur. Countries that can establish a “tolerable administration of justice” to secure property rights and allow investment and exchange to take place will see economic progress take place. Smith’s emphasis on a country’s “institutions” in determining its relative income has been supported by recent empirical work on economic development.

Knowledge-based Hierarchies: Using Organizations to Understand the Economy

Luis Garicano, Esteban Rossi-Hansberg

NBER Working Paper No. 20607, October 2014We argue that incorporating the decision of how to organize the acquisition, use, and communication of knowledge into economic models is essential to understand a wide variety of economic phenomena. We survey the literature that has used knowledge-based hierarchies to study issues like the evolution of wage inequality, the growth and productivity of firms, economic development, the gains from international trade, as well as offshoring and the formation of international production teams, among many others. We also review the nascent empirical literature that has, so far, confirmed the importance of organizational decisions and many of its more salient implications.

Update: See also Irwin’s article in Monday’s WSJ: “The Ultimate Global Antipoverty Program.”

“Why Managers Still Matter”

| Nicolai Foss |

Here is a recent MIT Sloan Management Review piece by Peter and me, “Why Managers Still Matter.” We pick up on a number of themes of our 2012 book Organizing Entrepreneurial Judgment. A brief excerpt:

Here is a recent MIT Sloan Management Review piece by Peter and me, “Why Managers Still Matter.” We pick up on a number of themes of our 2012 book Organizing Entrepreneurial Judgment. A brief excerpt:

“Wikifying” the modern business has become a call to arms for some management scholars and pundits. As Tim Kastelle, a leading scholar on innovation management at the University of Queensland Business School in Australia, wrote: “It’s time to start reimagining management. Making everyone a chief is a good place to start.”

Companies, some of which operate in very traditional market sectors, have been crowing for years about their systems for “managing without managers” and how market forces and well-designed incentives can help decentralize management and motivate employees to take the initiative. . . .

From our perspective, the view that executive authority is increasingly passé is wrong. Indeed, we have found that it is essential in situations where (1) decisions are time-sensitive; (2) key knowledge is concentrated within the management team; and (3) there is need for internal coordination. . . . Such conditions are hallmarks of our networked, knowledge-intensive and hypercompetitive economy.

SMS Teaching Workshop: Impact of New Technologies on Teaching and Higher Education

| Peter Klein |

Along with  Gonçalo Pacheco de Almeida I am chairing the Competitive Strategy Interest Group Teaching Workshop at the upcoming Strategic Management Society conference in Madrid. The workshop is Saturday, 20 September 2014, 1:00-4:00pm at the main conference venue, the NH Eurobuilding, Paris Room. Our theme is “The Impact of New Technologies on Teaching and Higher Education” and we have an all-star lineup featuring Bharat Anand (Harvard), Peter Zemsky (INSEAD), Michael Leiblein (Ohio State), Michael Lenox (University of Virginia), Frank Rothaermel (Georgia Tech), Vivek Goel (Chief Academic Strategist at Coursera), and Andrea Martin (President of IBM Academy of Technology).

Gonçalo Pacheco de Almeida I am chairing the Competitive Strategy Interest Group Teaching Workshop at the upcoming Strategic Management Society conference in Madrid. The workshop is Saturday, 20 September 2014, 1:00-4:00pm at the main conference venue, the NH Eurobuilding, Paris Room. Our theme is “The Impact of New Technologies on Teaching and Higher Education” and we have an all-star lineup featuring Bharat Anand (Harvard), Peter Zemsky (INSEAD), Michael Leiblein (Ohio State), Michael Lenox (University of Virginia), Frank Rothaermel (Georgia Tech), Vivek Goel (Chief Academic Strategist at Coursera), and Andrea Martin (President of IBM Academy of Technology).

Background: The higher-education industry is abuzz with talk about MOOCs, distance learning, computer-based instruction, and other pedagogical innovations. Many of you are already using online exercises and assessments, simulations, and other activities in the classroom. How are these innovations best incorporated into the business curriculum, at the BBA, MBA, EMBA, and PhD levels? What can business scholars, say about the impact of these technologies on higher education more generally? Are they sustaining or disruptive innovations, and what do they imply for the structure of the business school, and the university itself?

The plan for this session is to discuss how leading companies and business schools are (a) driving innovation in the Higher Education teaching space, (b) thinking about the business model of virtual education (MOOCs, social learning, etc.), and (c) testing some of the assumptions behind globalization in the education industry.

The full schedule is below the fold. Additional information about the workshop, and the SMS itself, is available at the conference website.

If you’re coming to SMS this year, please plan to join us for the workshop. Pre-registration is encouraged but not required. If you’re planning to attend, please let us know by sending an email to csig.teaching2014@gmail.com. Feel free to email Gonçalo or myself at the same address with questions or comments. (more…)

Debating Microfoundations, Euro-style

| Nicolai Foss |

As readers of this blog will know, probably to a nauseating extent, microfoundations have been central in much (macro) management theory over the last decade. Several articles, special issues, and conferences have been dedicated to microfoundations, most recently a Strategic Management Society Special Conference at the Copenhagen Business School. Some, uhm, highlyspirited exchanges have taken place (e.g., AoM 2013), with proponents of those foundations being accused of economics imperalism and whatnot, and critics of microfoundations receiving push-back for endorsing defunct Durkheimian collectivism (an obviously justified criticism). Here is recent civilized exchange on the subject between Professor Rodolphe Durand, HEC Paris, and myself. Complete with heavy Euro accents of different origins.

History Lesson: 200 Years of Management, uhm, Thought

| Nicolai Foss |

OK, surely you have come across those timelines featuring the great economists, á la Aristotle-the Spanish Scholastics–William Petty-Cantillon-Smith-Ricardo-Say-Menger-Wicksteed-Marshall-Mises-Hayek-Boettke-Langlois-Klein-etc. Here is a similar timeline with the Greats of management theory, 1800-2000 (Lien seems to be missing, however). Many of the names of those management types are clickable, taking you to e.g. their wikis. Fun brush-up, and may be good for students.

Making Money from Behavioral Social Science?

| Peter Klein |

Longtime readers of this blog expect skepticism about behavioral social science. One of my issues is the assumed, but unexplored, assumption that private actors and market institutions cannot deal with behavioral anomalies, and therefore government intervention is necessary to make people act “rationally.” But if we can really improve health outcomes by putting the chocolate cake behind the carrot sticks in the display case, why wouldn’t profit-seeking entrepreneurs exploit this fact? Consumers pay substantial price premiums for organic produce, grass-fed meats, and other healthy products, even when the purported health benefits are long-term and uncertain. Wouldn’t some patronize the behavioral-economics-influenced grocer? “Our shelves are arranged to encourage healthy food choices.” Add earth tones, hipster music, an onsite juice bar, and the place will make as much money as your local Whole Foods.

To be a little less flippant: consider adverse selection theory. Many people misread Akerlof’s famous paper as a call for government regulation of used-car markets (or, worse, as a demonstration that used-car markets can’t exist). In fact, as Akerlof states plainly in the original piece, his theory explains the existence of private assurance mechanisms such as warranties, third-party certification, quality signalling, and the like.

A recent Forbes piece puts it this way: How do you make money by helping mitigate behavioral anomalies? Cognitive biases “have been accepted into the mainstream of economics and pop culture, particularly since the recent publication of popular books such as Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein’s Nudge, Dan Ariely’s Predictably Irrational, and Daniel Kahneman’s Thinking, Fast and Slow. Even so, relatively few companies have attempted to use behavioral economics to try to change people’s behavior around overeating, smoking, or other bad habits many are desperate to break.” The focus is on the diet company StickK, which takes advantage of loss aversion (pun intended) to help people achieve weight and other goals.

StickK is a cool site, and I hope it is successful. But, if behavioral theory is so powerful and general, why aren’t more entrepreneurs taking advantage of it?

Louise Mors on Ambidexterity

| Nicolai Foss |

Margarethe Wiersema interviews my colleague Louise Mors about her forthcoming article in Organization Science on Ambidexterity.

The New Empirical Economics of Management

| Peter Klein |

That’s the title of a new review paper by Nicholas Bloom, Renata Lemos, Raffaella Sadun, Daniela Scur, and John Van Reenen, summarizing the recent large-sample empirical literature on management practices using the World Management Survey (modeled on the older World Values Survey). Here’s the NBER version and here’s an ungated version from the LSE’s Centre for Economic Performance.

This literature has been rightly criticized for its somewhat coarse, survey-based measures of management practices, but its measures are probably the most precise that can be reliably extracted from a large sample of firms across many countries. In that sense it is on par with the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor, the Economic Freedom Index, and other databases that attempt to capture subtle and ultimately subjective characteristics across a broad sample.

Here’s the abstract of the Bloom et al. paper:

Over the last decade the World Management Survey (WMS) has collected firm-level management practices data across multiple sectors and countries. We developed the survey to try to explain the large and persistent TFP differences across firms and countries. This review paper discusses what has been learned empirically and theoretically from the WMS and other recent work on management practices. Our preliminary results suggest that about a quarter of cross-country and within-country TFP gaps can be accounted for by management practices. Management seems to matter both qualitatively and quantitatively. Competition, governance, human capital and informational frictions help account for the variation in management.

It provides a nice overview for those new to this literature. An earlier review paper by Bloom, Genakos, Sadun, and Van Reenen, “Management Practices Across Firms and Countries,” appeared in the Academy of Management Perspectives in 2011, along with some critical comments by David Waldman, Mary Sully de Luque, and Danni Wang.

Is Human Capital Theory Compatible with the Strategy Literature?

[Another Becker-themed guest post, this one from former guest blogger Russ Coff, a leader in the emerging field of Strategic Human Capital.]

| Russ Coff |

Human capital theory (HCT) has brought a lot to the strategy literature. It has also held it back as scholars import logic that is inconsistent with core assumptions of the literature.

Before I launch into my heretical rant, let me acknowledge, as others have said so eloquently, Gary Becker was a truly innovative thinker. The most unique part was that, while he was firmly grounded in economic logic, he did not hesitate to venture into new terrain. Though he is most known for his work in HCT, his thoughtful explorations of marriage, discrimination, crime, and many other topics demonstrate the breadth and depth of his intellect.

However, strategy represents new terrain that is often inconsistent with the logic of HCT. In this sense, I think Becker would have relished the opportunity to examine this context as a new problem. Human capital challenges the strategy literature in the most fundamental ways possible – if we go beyond a cursory integration with Becker’s world. Here are some examples:

How much does firm-specific human capital (FSHC) matter? Drawing on HCT, scholars often assume firm specificity is important since it hinders mobility and allows the firm to capture rent. However, recent work suggests that this effect may be overstated. It requires strong information about human capital as opposed to the coarse signals that employers often rely upon. Thus, a worker moving from a successful firm may have ample opportunities as the firm’s success serves as a signal of the worker’s capabilities – FSHC investments are ignored. Even with strong information, individuals who invest in FSHC may be in demand by firms seeking employees who are willing and able to make such investments. When we consider such market imperfections (at the core of strategy theory), some of the classical HCT logic breaks down.

General human capital as a source of competitive advantage? Recent work in economics (Lazear’s skill-weights model) and the literature on stars focuses on workers who have skills that are valuable across firms. Both literatures point out how valuable and rare such skills can be (at very high levels). The scarcity and imperfect markets suggest that general human capital can be a source of advantage. Such people may be much more scarce and much less mobile than is assumed in classical HCT. Practitioners focus extensively on this type of knowledge. Can it lead to an advantage?

What is competitive advantage? From this, we might ask some more fundamental questions about competitive advantage, firms, and ownership. Most scholars implicitly adopt an agency theoretic view where shareholders are the only residual claimant and competitive advantage is therefore rent that flows to shareholders. Any value that flows to employees is considered not to have been captured by the firm. Joe Mahoney points out that shareholders would be the sole residual claimants if all factors are traded in perfectly competitive markets (e.g., wage = MRP). For this to be true, firms would have to be homogeneous and human capital would need to be a commodity. As such, this logic assumes away the possibility of competitive advantage altogether. If firms are heterogeneous and there are factor market failures, shareholders would not generally be sole residual claimants. What, then, is competitive advantage? (more…)

Recent Comments