Archive for December, 2010

Top Posts of 2010

| Peter Klein |

Our most popular post published in 2010:

Our most popular post published in 2010:

- Summary of Dodd-Frank Act

- Management Journal Impact Factors 2009

- Intellectual Steam

- How to Read an Academic Article

- The Era of Laissez-Faire?

- Does Behavioral Economics Offer Anything New and True?

- Pomo Periscope XX: Thomas Basbøll vs. Karl Weick

- Political and Methodological Individualism

- The Role of Assumptions in Management Research

- Ig Nobel Economics and Management Prizes

- Assessing the Critiques of the RBV

- PowerPoint Version of “I Have a Dream”

- Teaching Analytical Writing

- Ronald Coase’s New Book

- Isomorphism in Higher Education

Thanks to all our readers, commenters, linkers, lurkers, secret admirers, public admirers, etc. for a great 2010!

Google Tries Selective Intervention?

| Peter Klein |

Can a large firm do everything a collection of small firms can do, and more? If not, how do we understand the limits to organization? Arrow focused on the information structure inside firms. I favor Mises’s economic calculation argument. Williamson’s preferred explanation for the limits to the firm is the impossibility of selective intervention — the idea that higher-level managers cannot credibly commit to leave lower-level managers alone, except when such selective intervention would generate joint gains. Williamson’s argument is not, however, universally embraced (or even understood the same way — see the comments to Nicolai’s post).

Google apparently sees things Williamson’s way and has formulated an explicit policy on “autonomous units” designed to address the problem. Such units “have the freedom to run like independent startups with almost no approvals needed from HQ, ” reports TechCrunch. “For these divisions, Google is essentially a holding company that provides back end services like legal, providing office space and organizing travel, but everything else is up to the pseudo-startup.” Can it work? Insiders are doubtful. The TechCrunch reporter even frames Williamson’s thesis in this folksy way:

There’s a lie that companies and entrepreneurs tell themselves in order to commit to an acquisition.

Oh, we’re not going to change anything! We’re just going to give you more resources to do what you’ve been doing even better!

Yeah! They bought us for a reason, why would they ruin things?

It usually works for a little while, but big company bureaucracy– whether it’s HR, politics or just endless meetings– almost always creeps in. It’s a law of nature: Big companies just need certain processes to run and entrepreneurs hate those processes because they stifle nimble innovation.

Coordination Problems in the Theory of the Firm

| Nicolai Foss |

Many textbooks (e.g., this one or this one) begin by noting that there are two fundamental problems of economic organization, namely the coordination problem and the motivation problem — and then devote 95% of the space to the latter problem. (In a paper published in 1993 (but written in 1989), I proposed that extant theories of the firm could be understood as taking either a PD (-like) game or a coordination game as the fundamental underlying structure of interaction. In my reading, capabilities theories were about coordination problems, while mainstream organization economics fundamentally started from PD-like situations; this paper develops the argument a little bit).

Important work has been done on coordination problems in the context of the theory of the firm by Colin Camerer and Mark Knez (e.g., here), Phanish Puranam and Ranjay Gulati (here), Luis Garicano (e.g., here), Birger Wernerfelt (e.g., here), and, of course, co-blogger Dick Langlois (check his CV here on O&M — most of his stuff on economic organization is about coordination). One could also make the point that large parts of traditional organizational design theory (of the information processing/contingency variety, including Marschak & Radner’s team theory) are really about coordination problems rather than motivation problems. Dick Langlois has long argued that Coase (1937) is fundamentally about coordination rather than motivation.

This is definetely something; however, compared to the enormous outpouring of work on motivation problems, it is fair to say that coordination problems are neglected, although there are reasons to suppose that they are quite important: There are plenty of examples of highly motivated people utterly failing with respect to organizing and coordinating.

I just came across an excellent paper, “Coordination Neglect: How Lay Theories of Organizing Complicate Coordination in Organization,” that deals with a number of obstacles to coordination rooted in heuristics (“lay theories”) that individuals apply, for example, when setting up a division of labour in an organization. Notably, individuals systematically neglect task interdependencies. They also fail to communicate sufficiently because of knowledge bias and they are poor at translating problems for others. There are plenty of useful illustrations and anecdotes in the paper, making it excellent as a companion to a traditional motivation/incentive-focused textbook in a theory of the firm class. Highly recommended!

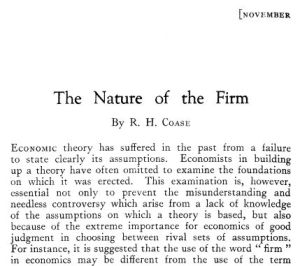

The Economist on Coase at 100

| Peter Klein |

The new Economist celebrates Ronald Coase’s 100th birthday (this coming Wednesday) with a short piece on “The Nature of the Firm” (1937), the founding document of modern organizational economics (16,379 Google Scholar cites). (Thanks to Avi for the pointer.) It’s nice to see the theory of the firm get its props, and the first few paragraphs do a good job summarizing the paper. But the (anonymous) author has misread the modern literature, first in setting up an artificial conflict between Coase’s transaction-cost approach and the resource-based approach to the firm and, second, by missing the depth and nuance of Coase’s own research program.

The new Economist celebrates Ronald Coase’s 100th birthday (this coming Wednesday) with a short piece on “The Nature of the Firm” (1937), the founding document of modern organizational economics (16,379 Google Scholar cites). (Thanks to Avi for the pointer.) It’s nice to see the theory of the firm get its props, and the first few paragraphs do a good job summarizing the paper. But the (anonymous) author has misread the modern literature, first in setting up an artificial conflict between Coase’s transaction-cost approach and the resource-based approach to the firm and, second, by missing the depth and nuance of Coase’s own research program.

On the first point: Much recent work tries to reconcile transaction cost economics (TCE) and the resource-based view (RBV) (e.g., Silverman, 1999; Foss and Langlois, 1999; Tsang, 2000; Madhok, 2002; Foss and Foss, 2005), pointing out that the two theories are, in important ways, complementary. Put simply: TCE and RBV start with different explananda. The RBV asks which resources will be combined in which ways to produce which outputs, while TCE asks how this activity will be organized (market, hierarchy, or hybrid). RBV offers a theory of competitive advantage, while TCE focuses on boundaries and governance. Second, the Economist writer confuses Coase with the (Coase-inspired) transaction cost approach of Williamson (1971, 1975, 1979) and Klein, Crawford, and Alchian (1978): (more…)

On the first point: Much recent work tries to reconcile transaction cost economics (TCE) and the resource-based view (RBV) (e.g., Silverman, 1999; Foss and Langlois, 1999; Tsang, 2000; Madhok, 2002; Foss and Foss, 2005), pointing out that the two theories are, in important ways, complementary. Put simply: TCE and RBV start with different explananda. The RBV asks which resources will be combined in which ways to produce which outputs, while TCE asks how this activity will be organized (market, hierarchy, or hybrid). RBV offers a theory of competitive advantage, while TCE focuses on boundaries and governance. Second, the Economist writer confuses Coase with the (Coase-inspired) transaction cost approach of Williamson (1971, 1975, 1979) and Klein, Crawford, and Alchian (1978): (more…)

Happy Holidays

| Peter Klein |

Warmest holiday wishes from the gang at O&M. We’re too lazy — I mean, too busy researching, writing, lecturing, etc. — to come up with a new holiday post, so we’ll just bask in the glories of past seasonal posts. To wit:

Democracy and Credible Commitment in Universities

| Nicolai Foss |

In 2003, Denmark enacted what is the easily the least democratic university legislation in the world (the North Korean one may be less democratic). Essentially, faculty voting rights are now limited to selecting members of an “academic council” which mainly serves as a quality check on candidates for evaluation committees and as a body that offers advice to the university president and the deans. A board of directors (with a majority of external members) appoints the president, the president appoints the dean, and the dean appoints department heads.

This truly major change was partly motivated by the various inefficiencies of the earlier, much more democratic conditions. However, as autocratic systems also have well-known inefficiencies, the question is whether Denmark let the governance pendulum swing too much toward the opposite end. My colleague Henrik Lando directed my attention to a truly excellent paper by O&M guest blogger Scott Masten that is directly relevant to the understanding of this issue. (more…)

Razors, Blades, and Bugattis

| Peter Klein |

I learn from Car and Driver that the tires for the new Bugatti Veyron 16.4 Super Sport run $42,000 a set, last only 10,000 miles, and require a $69,000 wheel replacement after the third tire change. Is Bugatti playing razors and blades? (The real strategy, not the apocryphal one.) Um, nope, this Veyron itself costs $2,426,904. That’s one damn fine razor!

I learn from Car and Driver that the tires for the new Bugatti Veyron 16.4 Super Sport run $42,000 a set, last only 10,000 miles, and require a $69,000 wheel replacement after the third tire change. Is Bugatti playing razors and blades? (The real strategy, not the apocryphal one.) Um, nope, this Veyron itself costs $2,426,904. That’s one damn fine razor!

Love, Marriage, and Money

| Peter Klein |

Most interesting passage I read today:

Contrary to prevailing interpretations that attribute the [historical] rise in voluntary, romantic unions to an increased sexual division of labor and the domestication of family life, Howell argues that true companionship between husband and wife was necessary to weather the challenges of commercial life. In her words, “love was by no means the antithesis of the market. It was the market’s helpmate” (p. 141).

It’s from Francesca Trivellato’s review of Martha C. Howell, Commerce before Capitalism in Europe, 1300-1600 (Cambridge, 2010). As Howell notes, “the commercialization of society was not just an economic history as we understand the term but a social, legal, and cultural story, and it is incomprehensible if told from the perspective of one of these modern conceptual categories alone.”

Short Course on Network Economics

| Peter Klein |

I’m teaching a five-week, online course starting in January called “Networks and the Digital Revolution: Economic Myths and Realities.” It’s offered through the Mises Academy, an innovative course-delivery platform that is becoming its own educational ecosystem. A description and course outline is here, signup information is here. I’d love to have you join me!

I’m teaching a five-week, online course starting in January called “Networks and the Digital Revolution: Economic Myths and Realities.” It’s offered through the Mises Academy, an innovative course-delivery platform that is becoming its own educational ecosystem. A description and course outline is here, signup information is here. I’d love to have you join me!

Friedman, 1953

| Lasse Lien |

Some things just cannot be ignored. A prime example is Friedman’s 1953 essay “The Methodology of Positive Economics.” As most O&M readers will know Friedman’s key claim is that a theory should be judged by its predictive accuracy, not the realism of its assumptions. On the contrary, a theory that makes dramatic (i.e., unrealistic) simplifying assumptions and still generates good predictive results is considered a better theory than a more complex (i.e., realistic) theory with the same predictive performance. Few texts, and surely no other text on economic methodology, is loved, hated, and cited by so many. In much of mainstream economics Friedman’s position — or some version thereof — is routinely relied upon. For example, imagine defending game theory on the realism of its assumptions.

In 2003, on the 50 year anniversary of its publication, a conference was held at the Erasmus University in Rotterdam where the legacy of this paper was discussed. In 2009 a book was published containing a collection of papers from this conference, edited by Uskali Mäki. A link to this book can be found here, and a recently published (harsh) review of the book can be found here. Note that the book review makes interesting reading even if you do not intend to read the book (but have read the original essay).

If this is your cup of tea, you might also like this remarkable paper.

Megachurches and Management Education

| Peter Klein |

This month’s Fast Company profiles Willow Creek, perhaps the world’s most famous megachurch. The article opens by describing a conversation between Willow Creek pastor Bill Hybels and management guru Peter Drucker:

Hybels decided that one of his unique contributions [to ministry] could be to create a resource for pastors who didn’t have firsthand access to thinkers like Drucker. The need was clear. A 1993 survey of evangelical pastors by seven seminaries found that while they said their education had prepped them well in church history and theology, they felt undertrained in administration, management, and strategic planning. “In the 1950s, a pastor preached on Sundays, did weddings and funerals, and visited the sick,” says Dennis Baril, senior pastor of the Community Covenant Church in Rehoboth, Massachusetts, which hosts a satellite summit site every year. “I have almost 50 ministries that need to be put together, scheduled, organized, and led. It’s a different skill set.”

Church conferences did little to address that need. “Most of them are pastors learning from pastors,” says Jim Mellado, who wrote a 1991 Harvard Business School case study on Willow Creek. “If you only hear preaching from the choir, you’re never stretched. You never see things from another perspective.”

Sounds a bit like university administrators, most of whom learn administration from, well, other university administrators. (Who may have been English professors in a previous life.)

Here’s the HBS case on Willow Creek, and here are Mike Porter’s PowerPoint slides from his 2007 presentation at Willow Creek’s leadership summit. Interesting factoid from the Economist via Wikipedia: in 2007, five of the world’s ten largest Protestant churches were in South Korea.

In Defense of English

| Peter Klein |

Co-bloggers Nicolai and Lasse probably speak better English than I do, despite the handicap of Scandinavian birth, but I sure like it. So does Rishidev Chaudhuri:

To me, the most striking thing about English is its diversity of vowels, something I only noticed after many years of speaking the language. English, in many dialects, has about 15 vowels (not counting diphtongs). Listen to the vowels through these words: a, kit, dress, trap, lot, strut, foot, bath, nurse, fleece, thought, goose, goat, north. There are languages that have more (Germanic ones tend to be vowel rich), but there aren’t many of them, and none that I know well enough to frame a sentence in. And compare this vowel list to the relative paucity of vowels in so many other languages. Hindi really has only about 9 or 10 vowels; Bengali, which has lost several long-short distinctions has slightly fewer (though lots of diphtongs). Some languages (including these two) do include extra vowels formed by nasalizing existing ones; these nasalized vowels often sound lovely, but feel very similar to their base vowels. It’s more a flourish than a genuinely new creation. Japanese and Spanish have about 4 or 5 apiece, and I’m told that Mandarin and Arabic have about 6.

English, then, is capable of exceptionally rich assonance and exuberant plays on vowel sound.

I mean, savor the delights of “methodological individualism” or “apodictic certainty” or “heteroskedasticity consistent standard errors” and tell me it isn’t sheer poetry!

“Robert S. McNamara and the Evolution of Modern Management”

| Peter Klein |

That’s the title of a new HBR article by Phil Rosenzweig (author of the excellent Halo Effect). I’ve been interested in McNamara and his role in business history since grad school, when I was researching “management by the numbers” and similar techniques that flourished during the conglomerate boom in the 1960s. (See previous O&M posts on McNamara here and here.) Rosenzweig provides a nice summary of some of strengths and weaknesses of McNamara’s dispassionate, “rational,” quantitative approach (see especially the sidebar, “What the Whiz Kids Missed”). Lots of information and ideas related to decision theory, organizational design, multitasking, performance evaluation, innovation, etc. Excerpt:

Whether at Ford or in the military, in business or pursuing humanitarian objectives, McNamara’s guiding logic remained the same: What are the goals? What constraints do we face, whether in manpower or material resources? What’s the most efficient way to allocate resources to achieve our objectives? In filmmaker Errol Morris’s Academy Award–winning documentary The Fog of War, McNamara summarized his approach with two principles: “Maximize efficiency” and “Get the data.”

Yet McNamara’s great strength had a dark side, which was exposed when the American involvement in Vietnam escalated. The single-minded emphasis on rational analysis based on quantifiable data led to grave errors. The problem was, data that were hard to quantify tended to be overlooked, and there was no way to measure intangibles like motivation, hope, resentment, or courage. . . .

Equally serious was a failure to insist that data be impartial. Much of the data about Vietnam were flawed from the start. This was no factory floor of an automobile plant, where inventory was housed under a single roof and could be counted with precision. The Pentagon depended on sources whose information could not be verified and was in fact biased. Many officers in the South Vietnamese army reported what they thought the Americans wanted to hear, and the Americans in turn engaged in wishful thinking, providing analyses that were overly optimistic.

Kiffin Goods

| Peter Klein |

US college football fans may appreciate this paper, written by three University of Tennessee economists:

Kiffin Goods

by Omer Bayar, William Neilson, and Stephen Ogden

February 2, 2010Abstract: In this paper, we investigate the possibility of a managerial input that experiences increasing compensation along with decreasing intensity. We call this type of input a “Kiffin Good” after the head football coach Lane Kiffin. We propose a novel production process that might lead to Kiffin behavior.

The Kiffin Good is described as the supply-side equivalent of the so-called Giffen Good — for the latter, the quantity demanded increases with price, while for the former, price rises as quantity falls. (Note that some of us have politically incorrect views on Mr. Giffen’s famous paradox.)

Ronald Coase’s New Book

| Peter Klein |

Yes, you read that correctly. Ronald Coase, who turns 100 later this month, has a new book coming out from Palgrave Macmillan and the Institute of Economic Affairs, How China Became Capitalist. It’s coauthored with Ning Wang, Coase’s former research assistant at Chicago and now an assistant professor at Arizona State, and scheduled for publication in June 2011.

Yes, you read that correctly. Ronald Coase, who turns 100 later this month, has a new book coming out from Palgrave Macmillan and the Institute of Economic Affairs, How China Became Capitalist. It’s coauthored with Ning Wang, Coase’s former research assistant at Chicago and now an assistant professor at Arizona State, and scheduled for publication in June 2011.

Examining the astonishing events that led to China’s transformation from a close socialist economy to an invincible manufacturing powerhouse of the global economy, How China Became Capitalist argues that the impact of events that led China to become capitalist could not have been predicted. From the death of Mao to China’s market reform and move to capitalism under the auspices of the Chinese Communist Party, How China Became Capitalist controversially argues that China’s growth potential will be inhibited in future without a vibrant market in ideas.

CFP: “Competition, Innovation and Rivalry”

| Peter Klein |

The European Society for the History of Economic Thought (ESHET) is having its 15th annual meeting 19-22 May 2011 at Bogazici University, Istanbul. A special themed section, headlined by keynoters (and O&M friends) Dick Nelson and Stavros Ioannides, is “Competition, Innovation and Rivalry”:

The way in which innovation has been described, categorised, contextualised and theorised by various figures as well as schools of thought in the discipline of economics warrants a thorough investigation from a history of economic thought perspective. Although it is a truism that some approaches in economics by focusing on the conditions of allocating resources efficiently within a static framework failed to consider innovation properly, other approaches by underscoring the evolutionary characteristics of the economy, and thus by paying attention to dynamic efficiency, aimed at shedding light on innovation in an explicit manner. Knowledge and entrepreneurship standing as natural ingredients of innovation, much debate has been devoted to the roles played by competition, rivalry and collaboration among economic actors. A corollary of this debate has been on the characterisation of different economic systems in boosting or hampering innovation. . . . We are interested in papers that expose the history of economic ideas concerning innovation, competition and rivalry as well as papers that provide a historical or methodological perspective concerning methodological, ideological and political debates which evolved around these concepts.

Abstracts are due 15 December; see the above link for details.

Henry Manne on Behavioral Economics

| Peter Klein |

Henry Manne’s contribution to the Truth on the Market symposium on behavioral economics brought to mind Lasse’s recent post (and the accompanying brilliant paper) on the survivor principle:

What I would like to point out . . . is the irrelevance of much of the substance of Behavioral Economics for “doing” economics. My principal (as a matter of fact my sole) authority for this proposition (though some of Gary Becker’s work also comes to mind) is the magnificent classic article by Armen Alchian, Uncertainty, Evolution, and Economic Theory, 58 JPE 211 (1950). In this work Alchian is himself taking on the “full information” assumption of the classical model, which is actually broader than the rationality assumption attacked by the Behavioralists. The basic conclusion of that work is that, even if individuals or firms make totally uniformed choices (to say nothing of merely somewhat irrational ones) the end result as far as the allocation of resources is concerned will be the same as in the traditional model. This is so because the theory of competition in the classical model is itself a survival theory, and the survival mechanism will operate to winnow out the less efficient uses to which resources will unknowingly or irrationally be put, even if the human actors don’t understand the process or their role in it. Of course, an economy based on this (again) purely heuristic assumption of perfect ignorance would not be as productive as one in which information and rationality play their usual assigned roles, but the difference may not be so great as would first appear and there is nothing peculiar or earth-shattering about finding that there are transactions costs in the world and that in equilibrium they will be accounted for. And, as one begins to add notions of imitation and improvement, as Alchian does, one gets very close to a highly descriptive model of the real economy, and one which has plenty of room in it for all sorts of irrational behavior but without throwing the received theory out with the bath water.

The point that behavioral economics neglects the role of market competition as a moderator between individual behavior and aggregate outcomes is a good one. (We’ve discussed other problems with behavioral approaches before.) Still, I side with Kirzner in his debate with Becker; an entrepreneurial view of the market requires some notion of purpose or intent — I prefer the term judgment — but one far removed from the neoclassical economics, straw-man notion of “rationality” attacked by the behaviorists.

My Proudest Academic Achievement

| Peter Klein |

I’ve produced so many seminal papers in my long and distinguished career that I can’t name them all. Um, I can’t name any, actually. But here’s one for the ages: “‘They Have the Internet on Computers Now?’ Entrepreneurship and Economics in the Simpsons.” It’s coauthored with talented Missouri PhD students Per L. Bylund and Christopher H. Holbrook and is forthcoming in Joshua Hall, ed., Homer Economicus: The Simpsons and Economics (Springer, 2011), which should be on every economics and management teacher’s bookshelf.

Palgrave Entry on Oliver Williamson

| Scott Masten |

If you have access to The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics, Online Edition, my entry on Oliver Williamson is now available: Oliver E. Williamson.

History of Agricultural Research to 1945

| Peter Klein |

The importance of agricultural research in the intellectual history of science should be self-evident. Justus Liebig (1803-1873) was a key figure in both the development of laboratory methodology and agricultural science. Gregor Mendel’s (1822-1884) famous experiments were in plant breeding. Louis Pasteur’s (1822-1895) most celebrated work was on the cattle disease, anthrax. William Bateson (1861-1926), who coined the term genetics, was the first director of the John Innes Horticultural Institution in London, 1910-1926. Statistician, geneticist, and eugenics proponent R. A. Fisher (1890-1962) was employed by the Rothamsted Experimental Station, 1919 to 1933 (and temporarily relocated there from 1939 to 1943). Interwar and postwar virologists and molecular biologists did a great deal of work on the economically destructive tobacco mosaic virus.

From a very informative post at the history-of-science blog Ether Wave Propaganda (via Randy). In economics and management we’d have to add large swathes of production economics and risk-management research, the early papers in agency and contract theory dealing with sharecropping and land tenure, Grilliches’s work on hybrid corn, and much more. What else would you put on the list?

Recent Comments