Posts filed under ‘Business/Economic History’

Is Economic History Dead?

| Peter Klein |

An interesting piece in The Economist: “Economic history is dead; long live economic history?”

Last weekend, Britain’s Economic History Society hosted its annual three-day conference in Telford, attempting to show the subject was still alive and kicking. The economic historians present at the gathering were bullish about the future. Although the subject’s woes at MIT have been echoed across research universities in both America and Europe, since the financial crisis there has been something of a minor revival. One reason for this may be that, as we pointed out in 2013, it is widely believed amongst scholars, policy makers and the public that a better understanding of economic history would have helped to avoid the worst of the recent crisis.

However, renewed vigour can be most clearly seen in the debates economists are now having with each other.

These debates are those about the long-run relationship between debt and growth initiated by Reinhart and Rogoff, about the historic effectiveness of Keynesian monetary and fiscal policy, and about the role of global organizations like the IMF and World Bank in promoting international coordination.

I guess my view is closer to Andrew Smith’s, that while history should play a stronger role in economics (and management) research and teaching, it probably won’t, for a variety of professional and institutional reasons. Of course, there is a difference between, say, research in economic or business history and “papers published in journals specializing in economic or business history.” In the first half of the twentieth century, quantitative economics was treated as a specialized subfield; now virtually all mainstream economics is quantitative. (The same may happen to empirical sociology, to theorizing in strategic management, and in other areas.)

Microeconomics of War

| Peter Klein |

The old Keynesian idea that war is good for the economy is not taken seriously by anyone outside the New York Times op-ed page. But much of the discussion still focuses on macroeconomic effects (on aggregate demand, labor-force mobilization, etc.). The more important effects, as we’ve often discussed on these pages, are microeconomic — namely, resources are reallocated from higher-valued, civilian and commercial uses, to lower-valued, military and governmental uses. There are huge distortions to capital, labor, and product markets, and even technological innovation — often seen as a benefit of wars, hot and cold — is hampered.

A new NBER paper by Zorina Khan looks carefully at the microeconomic effects of the US Civil War and finds substantial resource misallocation. Perhaps the most significant finding relates to entrepreneurial opportunity — individuals who would otherwise create significant economic value through establishing and running firms, developing new products and services, and otherwise improving the quality of life are instead motivated to pursue government military contracts (a point emphasized in the materials linked above). Here is the abstract (I don’t see an ungated version, but please share in the comments if you find one):

The Impact of War on Resource Allocation: ‘Creative Destruction’ and the American Civil War

B. Zorina Khan

NBER Working Paper No. 20944, February 2015What is the effect of wars on industrialization, technology and commercial activity? In economic terms, such events as wars comprise a large exogenous shock to labor and capital markets, aggregate demand, the distribution of expenditures, and the rate and direction of technological innovation. In addition, if private individuals are extremely responsive to changes in incentives, wars can effect substantial changes in the allocation of resources, even within a decentralized structure with little federal control and a low rate of labor participation in the military. This paper examines war-time resource reallocation in terms of occupation, geographical mobility, and the commercialization of inventions during the American Civil War. The empirical evidence shows the war resulted in a significant temporary misallocation of resources, by reducing geographical mobility, and by creating incentives for individuals with high opportunity cost to switch into the market for military technologies, while decreasing financial returns to inventors. However, the end of armed conflict led to a rapid period of catching up, suggesting that the war did not lead to a permanent misallocation of inputs, and did not long inhibit the capacity for future technological progress.

Upcoming Workshops, Seminars, and Events

| Peter Klein |

Some upcoming events of interest to O&M readers:

- “Research and Policy Change Inspired by Ronald Coase,” 27-28 March 2015, Washington DC

- Berkeley-Paris Organizational Economics Workshop, 10-11 April 2015, Paris

- BHC/EBHA Workshop Historical Approaches to Entrepreneurship Theory & Research, 24 June 2015, Miami FL

- TILEC Economic Governance Workshop, “Economic Governance and Social Preferences,” 3-4 September 2015, Tilburg

Team Science and the Creative Genius

| Peter Klein |

We’ve addressed the widely held, but largely mistaken, view of creative artists and entrepreneurs as auteurs, isolated and misunderstood, fighting the establishment and bucking the conventional wisdom. In the more typical case, the creative genius is part of a collaborative team and takes full advantage of the division of labor. After all, is our ability to cooperate through voluntary exchange, in line with comparative advantage, that distinguishes us from the animals.

We’ve addressed the widely held, but largely mistaken, view of creative artists and entrepreneurs as auteurs, isolated and misunderstood, fighting the establishment and bucking the conventional wisdom. In the more typical case, the creative genius is part of a collaborative team and takes full advantage of the division of labor. After all, is our ability to cooperate through voluntary exchange, in line with comparative advantage, that distinguishes us from the animals.

Christian Caryl’s New Yorker review of The Imitation Game makes a similar point about Alan Turing. The film’s portrayal of Turing (played by Benedict Cumberbatch) “conforms to the familiar stereotype of the otherworldly nerd: he’s the kind of guy who doesn’t even understand an invitation to lunch. This places him at odds not only with the other codebreakers in his unit, but also, equally predictably, positions him as a natural rebel.” In fact, Turing was funny and could be quite charming, and got along well with his colleagues and supervisors.

As Caryl points out, these distortions

point to a much broader and deeply regrettable pattern. [Director] Tyldum and [writer] Moore are determined to suggest maximum dramatic tension between their tragic outsider and a blinkered society. (“You will never understand the importance of what I am creating here,” [Turing] wails when Denniston’s minions try to destroy his machine.) But this not only fatally miscasts Turing as a character—it also completely destroys any coherent telling of what he and his colleagues were trying to do.

In reality, Turing was an entirely willing participant in a collective enterprise that featured a host of other outstanding intellects who happily coexisted to extraordinary effect. The actual Denniston, for example, was an experienced cryptanalyst and was among those who, in 1939, debriefed the three Polish experts who had already spent years figuring out how to attack the Enigma, the state-of-the-art cipher machine the German military used for virtually all of their communications. It was their work that provided the template for the machines Turing would later create to revolutionize the British signals intelligence effort. So Turing and his colleagues were encouraged in their work by a military leadership that actually had a pretty sound understanding of cryptological principles and operational security. . . .

The movie version, in short, represents a bizarre departure from the historical record. In fact, Bletchley Park—and not only Turing’s legendary Hut 8—was doing productive work from the very beginning of the war. Within a few years its motley assortment of codebreakers, linguists, stenographers, and communications experts were operating on a near-industrial scale. By the end of the war there were some 9,000 people working on the project, processing thousands of intercepts per day.

The rebel outsider makes for good storytelling, but in most human endeavors, including science, art, and entrepreneurship, it is well-organized groups, not auteurs, who make the biggest breakthroughs.

The Medieval Enlightenment in Economic Thought

| Dick Langlois |

Attending academic presentations as a spectator – a pure consumer – can be great fun. On November 20, I drove up to Boston for one day of a wonderful conference, put together by the Business History program at Harvard Business School, on the History of Law and Business Enterprise (which probably merited its own separate blog post). This is an area that I am starting to get interested in. The conference was in many ways a showcase for the GHLR perspective on the history of corporate organization – the acronym referring to the work of Timothy Guinnane, Naomi Lamoreaux, Ron Harris, and Jean-Laurent Rosenthal, all of whom were there. The conference took place across the street from Harvard Stadium on the weekend of the Harvard-Yale game. Harvard won the football game (alas), but the conference was a Yale rout.

And last week I attended a presentation here at UConn that was even more vicarious fun. Our Humanities Institute invited Joel Kaye from Barnard to talk about his new book, A History of Balance, 1250-1375: The Emergence of a New Model of Equilibrium and Its Impact on Thought, which has just appeared from Cambridge. I was the token economist in the audience, even though two of his chapters are about economics. His argument is that medieval scholastic thought changed radically over this period, and produced by its end a different and arguably more sophisticated model of how the economic world works. This “new” model is not the standard Aristotelian version we are normally told about but was in fact something far closer to the views of the Scottish Enlightenment. (Needless to say, his telling of this was far more nuanced.) In addition to Nicole Oresme, whom I had heard of, he relies heavily on the work of Peter John Olivi, an earlier Franciscan theologian, whom I had never heard of. In Kaye’s telling, Olivi came close to something like the idea of the invisible hand. I took a quick look at standard history-of-thought texts, and nobody mentions Olivi at all – except Murray Rothbard, who credits him with discovering the subjective theory of value.

This is really a story about the Enlightenment of the High Middle Ages, which took place among academic clerics in an age of population growth, (extensive) economic growth, and urbanization. As Kaye apparently argues in an earlier book, these academics were constantly confronted with the market – especially in the thriving city of Paris – and were well versed in market practice; indeed, this knowledge of the market and money contributed to advances in physical and biological as well as social sciences. The medieval academic Enlightenment went into decline after the Black Death in the early fourteenth century. The resulting dislocations and the swing in relative prices – in favor of peasants and against landholders, including importantly the Church – reduced the centrality and authority of academic thought, even as they spurred institutional changes that would set the stage for growth in the early modern period. Population in Europe did not return to its pre-plague levels until the sixteenth or seventeenth century, and economic thought took just as long to recover. (I know this is whiggish, but I can’t help it.)

There was perhaps one connection between the two events. At HBS, Ron Harris talked about his ongoing research on the earliest history of the corporate form in the East and the West. Here the commenda contract is the centerpiece. That is presumably what schoolmen like Olivi called by the Latin term societas, which was not, however, the same institution as the societas publicanus of ancient Rome.

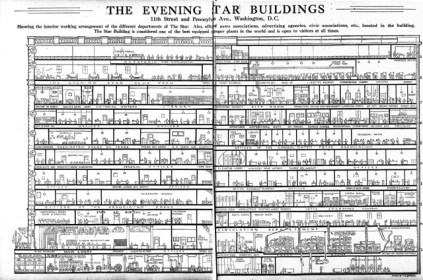

An Information Flow Diagram from 1922

| Peter Klein |

We’ve featured some cool vintage diagrams before, such as the New York and Erie Railroad organizational chart and the diagrams of the Mundaneum. Here’s an information flow diagram from 1922, represented as a cutaway view of the Washington Star newspaper offices. As Jason Kottke notes, it provides “a fascinating view of how information flowed through a newspaper company in the 1920s. Raw materials in the form of electricity, water, telegraph messages, paper, and employees enter the building and finished newspapers leave out the back.”

Bottom-up Approaches to Economic Development

| Peter Klein |

Via Michael Strong, a thoughtful review and critique of Western-style economic development programs and their focus on one-size-fits-all, “big idea” approaches. Writing in the New Republic, Michael Hobbs takes on not only Bono and Jeff Sachs and USAID and the usual suspects, but even the randomized-controlled-trials crowd, or “randomistas,” like Duflo and Banerjee. Instead of searching for the big idea, thinking that “once we identify the correct one, we can simply unfurl it on the entire developing world like a picnic blanket,” we should support local, incremental, experimental, attempts to improve social and economic well being — a Hayekian bottom-up approach.

We all understand that every ecosystem, each forest floor or coral reef, is the result of millions of interactions between its constituent parts, a balance of all the aggregated adaptations of plants and animals to their climate and each other. Adding a non-native species, or removing one that has always been there, changes these relationships in ways that are too intertwined and complicated to predict. . . .

[I]nternational development is just such an invasive species. Why Dertu doesn’t have a vaccination clinic, why Kenyan schoolkids can’t read, it’s a combination of culture, politics, history, laws, infrastructure, individuals—all of a society’s component parts, their harmony and their discord, working as one organism. Introducing something foreign into that system—millions in donor cash, dozens of trained personnel and equipment, U.N. Land Rovers—causes it to adapt in ways you can’t predict.

Microeconomics of Central Banking

| Peter Klein |

I have a chapter in a new book edited by David Howden and Joseph Salerno, The Fed at One Hundred: A Critical View on the Federal Reserve System (New York: Springer, 2014). My chapter is called “Information, Incentives, and Organization: The Microeconomics of Central Banking,” and builds upon themes discussed many times on this blog, such as Fed independence. Here is a SSRN version of the chapter. The book comes out next month but you can pre-order at the Amazon link above.

The Use of History in Management Research and Education

| Peter Klein |

Another book recommendation, also courtesy of EH.Net. The book is Organizations in Time: History, Theory, Methods (Oxford University Press, 2014), edited by Marcelo Bucheli and R. Daniel Wadhwani. (Bucheli is author of an excellent book on the United Fruit Company.) Organizations in Time is about of the use of history in management research and education. Perhaps surprisingly, the field of business history is not usually part of the business school curriculum. In the US at least, business historians are typically affiliated with history or economics departments, not management departments or other parts of the business school. EH.Net reviewer Andrew Smith notes the following:

Until the 1960s, economic history and business history had an important place in business school teaching and research. Many management scholars then decided to emulate research models developed in the hard sciences, which led to history becoming marginal in most business schools. History lost respect among positivistic management academics because historians made few broad theoretical claims, rarely discussed their research methodologies, and did not explicitly identify their independent and dependent variables. Historians in management schools became, effectively, disciplinary guests in their institutions.

The period from 2008 to the present has witnessed a revival of interest in history on the part of consumers of economic knowledge in a variety of academic disciplines, not to mention society as a whole. . . . It is now widely recognized that there needs to be more history in business school research and teaching. However, as Marcelo Bucheli and Dan Wadhwani note in the introductory essay, this apparent consensus obscures a lack of clarity about what a “historic turn” would, in practice, involve (p. 5).

This volume argues that the historic turn cannot simply be about going to the historical record to gather data points for the testing of various social-scientific theories, which is what scholars such as Reinhart and Rogoff do. Rather than being yet another device for allowing the quantitative social sciences to colonize the past, the historic turn should involve the adoption of historical methods by other management school academics. At the very least, people in the field of organization studies should borrow more tools from the historian’s toolkit.

Read the book (or at least the review) to learn more about these tools and approaches, which involve psychology, embeddedness, path dependence, and other concepts familiar to O&M readers.

Competition in Early Telephone Networks

| Peter Klein |

As with other technologies involving network effects, the early telephone industry featured competing, geographically overlapping networks. Robert MacDougall provides a fascinating history of this period in The People’s Network: The Political Economy of the Telephone in the Gilded Age (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2013). From the book blurb:

As with other technologies involving network effects, the early telephone industry featured competing, geographically overlapping networks. Robert MacDougall provides a fascinating history of this period in The People’s Network: The Political Economy of the Telephone in the Gilded Age (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2013). From the book blurb:

In the decades around 1900, ordinary citizens—farmers, doctors, small-town entrepreneurs—established tens of thousands of independent telephone systems, stringing their own wires to bring this new technology to the people. Managed by opportunists and idealists alike, these small businesses were motivated not only by profit but also by the promise of open communication as a weapon against monopoly capital and for protection of regional autonomy. As the Bell empire grew, independents fought fiercely to retain control of their local networks and companies—a struggle with an emerging corporate giant that has been almost entirely forgotten.

David Hochfelder wrote a thoughtful review which appeared today on EH.Net. As Hochfelder points out, the history of the telephone is not just about technology and market structure, but broader social themes as well:

At one level, this is a story about industrial competition. At a deeper level, it reveals competing visions of an important technology, the social role that it ought to play. MacDougall shows that the Bell System and the Independents envisioned the telephone in far different ways. Bell, especially under Theodore Vail, president of AT&T between 1907 and 1919, sought to build a unified telecommunications network that spanned the United States. Bell Canada espoused a different vision, that the telephone ought to remain an expensive urban medium primarily used for business purposes. Both Bell systems shared the ideology that the telephone industry ought to be controlled by centralized, national corporations. On the other hand, the Independents described the Bell System as a grasping octopus that wanted a stranglehold over the nation’s communications. The Independents offered instead a vision of the telephone as a people’s network that enhanced local ties and preserved community autonomy. In the United States, MacDougall claims that the Independents’ vision for the telephone “descended from a civic understanding of communication that went back to the American Revolution,” that “free and open communications were a basic ingredient of democracy” (p. 5). On a more mundane level, the Independents encouraged social uses of the telephone — like gossiping and banjo-playing — that the Bell System actively discouraged at the time.

Knowledge Elites, Inequality, and Economic Growth

| Peter Klein |

An interesting paper from Mara P. Squicciarini and Nico Voigtländer examines the role of “knowledge elites” — individuals at the upper tail of the human capital distribution* — in French economic growth around the time of the Industrial Revolution. Key passage:

To measure the historical presence of knowledge elites, we use city-level subscriptions to the famous Encyclopédie in mid-18th century France. We show that subscriber density is a strong predictor of city growth after 1750, but not before the onset of French industrialization. Alternative measures of development confirm this pattern: soldier height and industrial activity are strongly associated with subscriber density after, but not before, 1750. Literacy, on the other hand, does not predict growth. Finally, by joining data on British patents with a large French firm survey from 1837, we provide evidence for the mechanism: upper tail knowledge raised the productivity in innovative industrial technology.

In other words, growth is driven by the knowledge (and, presumably, skills, preferences, and beliefs) of the elites, not the population at large.

Squicciarini and Voigtländer don’t deal directly with the distribution of income and wealth (they do show that regions with higher Encyclopédie subscriber density had higher per-capita incomes), presumably those individuals in the upper tail of the knowledge distribution were also one-percenters in income or wealth. This brings to mind one of Bertrand de Jouvenel’s arguments about inequality, namely that it spurs technological innovation:

[I]t is a commonplace that things which are now provided inexpensively to the many, say spices or the newspaper, were originally luxuries which could be offered only because some few were willing and able to buy them at high prices. It is difficult to say what the economic development of the West would have been . . . if the productive effort had been aimed at providing more of the things needed by all, to the exclusion of a greater variety of things desired by minorities [i.e., elites]. . . . History shows us that each successive enlargement of the opportunities to consume was linked with unequal distribution of the means to consume.

I suspect Squicciarini and Voigtländer’s knowledge elites were largely the same as de Jouvenel’s “minorities” (in a robustness check for reverse causation, Squicciarini and Voightländer use membership in scientific societies as a proxy for knowledge elites, and these scientific societies were the primary producers and consumers of scientific instruments, for example). What would Monsieur Piketty say about this, I wonder?

The Paradox of the New Economic History

| Peter Klein |

MIT’s Peter Temin on the “paradox of the New Economic History,” from his keynote speech to the BETA-Workshop in Historical Economics (published as an NBER working paper):

New economic historians have turned their back on traditional historians and sought their place among economists. This has provided good jobs for many scholars, but the acceptance by economists is still incomplete. We therefore have two challenges ahead of ourselves. The first is to argue that economic development can only be fully understood if we understand the divergent histories of high-wage and low-wage economies. And the other big challenge is to translate our economic findings into historical lessons that historians will want to read. These challenges come from our place between economics and history, and both are important for the future of the New Economic History.

His broader claim is that the disciplines of economic history and economic development should be more closely integrated. “Both subfields study economic development; the difference is that economic history focuses on high-wage countries while economic development focuses on low-wage economies.”

Corporate Governance in the 19th Century

| Peter Klein |

A new NBER paper on 19th-century manufacturing firms in Massachusetts finds that incorporation rates, ownership concentration, and and managerial ownership varied systematically with technology (factory versus artisanal production, use of unskilled labor, etc.). In other words, governance forms were not determined primarily by the legal or regulatory environment, social and cultural issues, the desire for legitimacy, or other noneconomic factors, but by standard agency considerations.

Corporate Governance and the Development of Manufacturing Enterprises in Nineteenth-Century Massachusetts

Eric Hilt

NBER Working Paper No. 20096, May 2014This paper analyzes the use of the corporate form among nineteenth-century manufacturing firms in Massachusetts, from newly collected data from 1875. An analysis of incorporation rates across industries reveals that corporations were formed at higher rates among industries in which firm size was larger. But conditional on firm size, the industries in which production was conducted in factories, rather than artisanal shops, saw more frequent use of the corporate form. On average, the ownership of the corporations was quite concentrated, with the directors holding 45 percent of the shares. However, the corporations whose shares were quoted on the Boston Stock Exchange were ‘widely held’ at rates comparable to modern American public companies. The production methods utilized in in different industries also influenced firms’ ownership structures. In many early factories, steam power was combined with unskilled labor, and managers likely performed a complex supervisory role that was critical to the success of the firm. Consistent with the notion that monitoring management was especially important among such firms, corporations in industries that made greater use of steam power and unskilled labor had more concentrated ownership, higher levels of managerial ownership, and smaller boards of directors.

Contracts as Technology

| Peter Klein |

That’s the title of an interesting new law review article by Kevin Davis (New York University Law Review, April 2013). Just as we can treat organizational structure as as sort of technology, and study the introduction and diffusion of new organizational forms with the same theories and methods used to study technological innovation and diffusion, we can think of contracts as structures or institutions that emerge, are subject to experimentation and competition, and evolve and diffuse. Here’s the abstract:

If technology means, “useful knowledge about how to produce things at low cost”, then contracts should qualify. Just as mechanical technologies are embodied in blueprints, technologies of contracting are embodied in contractual documents that serve as, “blueprints for collaboration”. This Article analyzes innovations in contractual documents using the same kind of framework that is used to analyze other kinds of technological innovation. The analysis begins by laying out an informal model of the demand for and supply of innovative contractual documents. The discussion of demand emphasizes the impact of innovations upon not only each party’s incentives to collaborate efficiently, but also upon reading costs and litigation costs. The analysis of supply considers both the generation and dissemination of innovations and emphasizes the importance of cumulative innovation, learning by-doing, economies of scale and scope, and trustworthiness. Recent literature has raised concerns about the extent to which law firms produce contractual innovations. In fact, a wide range of actors other than law firms supply contractual documents; including end users of contracts, specialized providers of legal documents, legal database firms, trade associations, and academic institutions. This article discusses the incentives and capabilities of each of these potential sources of innovation. It concludes by discussing potential interventions such as: (1) enhancing intellectual property rights, (2) relaxing rules concerning the unauthorized practice of law and, (3) creating or expanding publicly sponsored clearinghouses for contracts.

See also Lisa Berstein’s comment. (HT: Geoff Manne)

Creativity and Age

| Peter Klein |

| Peter Klein |

A common myth is that successful technology companies are founded by people in their 20s (Scott Shane reports a median age of 39). Entrepreneurial creativity, in this particular sense, may peak at middle age.

We’ve previously noted interesting links between the literatures on artistic, scientific, and entrepreneurial creativity, organization, and success, with particular reference to recent work by David Galenson. A new survey paper by Benjamin Jones, E.J. Reedy, and Bruce Weinberg on age and scientific creativity is also relevant to this discussion. They discuss the widely accepted empirical finding that scientific creativity — measured by high-profile scientific contributions such as Nobel Prizes — tends to peak in middle age. They also review more recent research on variation in creativity life cycles across fields and over time. Jones, for example, has observed that the median age of Nobel laureates has increased over the 20th century, which he attributes to the rapid growth in the body of accumulated knowledge one must master before making a breakthrough scientific contribution (the “burden of knowledge” thesis). Could the same hold through for founders of technology companies?

Focused Firms and Conglomerates: Let a Thousand Flowers Bloom

| Peter Klein |

A renewed interest in conglomerates has brought forth a HBR blog post from Herman Vantrappen and Daniel Deneffe, “Don’t Write Off the (Western) Focused Firm Yet.” As they rightly point out, the choice between a focus and diversity “depends on the context in which the business operates. Specifically, focused firms fare better in countries where society expects and gets public accountability of both firms and governments, while conglomerates succeed in nations with high public accountability deficits.” I would put it slightly differently: the choice between focused, single-business firms and diversified, multi-business enterprises depends on the relative performance of internal and external capital and labor markets. The institutional environment — the legal system, regulatory practices, accounting rules — plays a huge rule here, but social norms, technology, and the competitive environment also affect the efficient margin between between intra-firm and inter-firm resource allocation.

The point is that all forms of organization have costs and benefits. There is no uniquely “optimal” degree of diversification or hierarchy or vertical integration or any other aspect of firm structure; the choice depends on the circumstances. Instead of favoring one particular organizational form we should be promoting an environment in which entrepreneurs can experiment with different approaches, with competition determining the right choice in each context. Let a thousand flowers bloom!

Update: From Joe Mahoney I learn that not only was Chairman Mao’s actual exhortation “Let a hundred flowers blossom,” but also he may have meant it sarcastically: “It is sometimes suggested that the initiative was a deliberate attempt to flush out dissidents by encouraging them to show themselves as critical of the regime.” My usage was of course sincere. :)

The Modular Kimono

| Dick Langlois |

I recently ran across this interesting paper on vertical integration and subcontracting in the Japanese kimono industry of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. By this period, most of the Japanese silk (and cotton) industries had adopted the factory system. But there remained a few industrial districts that relied on the putting-out system. This paper is most interested in presenting a risk-aversion model that explains why “premier subcontractors” got relational contracts in the putting-out system. I’m not sure I buy it, but in any case what caught my eye was something else — a modularity story:

In the weaving industry of Kiryu, the factory system equipped with hand looms had been chosen to weave the luxury fabrics, while the putting-out system had been used for most other fabrics, until the factory system equipped with power looms became dominant for most kinds of fabrics in the 1910s and later. Instead of being replaced, the putting-out system developed and dispersed within Kiryu, especially from the 1860s to the 1900s, when the main products of Kiryu were yarn-dyed silk fabrics. “Yarn dying” means material yarn is dyed before weaving. For the luxury fabrics that were dyed after weaving, the cleaning and finishing processes undertaken after weaving were important, and those processes were conducted inside the manufacturers’ workshops. In contrast, in the production of the yarn-dyed fabrics, dying, arranging warps, cleaning yarn, throwing, re-reeling, and other preparation processes were essential. Because those processes needed special skills, the craftsmen who specialized in each process were organized as subcontractors by manufacturers. … With the moving weight from production of traditional piece-dyed (dyed-after-weaving) fabrics to production of yarn-dyed (dyed-before-weaving) silk fabrics, the throwing process, the finishing process, and the designing process, as well as the weaving process, came to be put-out. Manufacturers decreased the production inside of their workshops and established subcontracting relations with independent artisans. This case suggests that the technological change induced by the change of products from piece-dyed fabrics to the yarn-dyed fabrics affected production organization.

This has a bit of a Christensen flavor to it. When “performance” needs were high — high-end kimonos — the industry used a non-modular technology (dyed-after-weaving) and an integrated organization. When performance needs were lower — lower-quality kimonos — it used a modular technology (dyed-before-weaving) and a vertically disintegrated structure.

Top Posts of 2013

| Peter Klein |

It’s been another fine year at O&M. 2013 witnessed 129 new posts, 197,531 page views, and 114,921 unique visitors. Here are the most popular posts published in 2013. Read them again for entertainment and enlightenment!

- Rise of the Three-Essays Dissertation

- Ronald Coase (1910-2013)

- Sequestration and the Death of Mainstream Journalism

- Post AoM: Are Management Types Too Spoiled?

- Nobel Miscellany

- The Myth of the Flattening Hierarchy

- Climate Science and the Scientific Method

- Bulletin: Brian Arthur Has Just Invented Austrian Economics

- Solution to the Economic Crisis? More Keynes and Marx

- Armen Alchian (1914-2013)

- My Response to Shane (2012)

- Your Favorite Books, in One Sentence

- Does Boeing Have an Outsourcing Problem?

- Doug Allen on Alchian

- New Paper on Austrian Capital Theory

- Hard and Soft Obscurantism

- Mokyr on Cultural Entrepreneurship

- Microfoundations Conference in Copenhagen, June 13-15, 2014

- On Academic Writing

- Steven Klepper

- Entrepreneurship and Knowledge

- Easy Money and Asset Bubbles

- Blind Review Blindly Reviewing Itself

- Reflections on the Explanation of Heterogeneous Firm Capability

- Do Markets “React” to Economic News?

Thanks to all of you for your patronage, commentary, and support!

Business Groups in the US

| Peter Klein |

Diversification continues to be a central issue for strategic management, industrial organization, and corporate finance. There are huge research and practitioner literatures on why firms diversify, how diversification affects financial, operating, and innovative performance, what underlies inter-industry relatedness, how diversification ties into other aspects of firm strategy and organization, whether diversification is driven by regulation or other policy choices, and so on. There are many surveys of these literatures (Lasse and I contributed this one).

Some of the most interesting research deals with the institutional environment. For example, many US corporations were widely diversified in the 1960s and 1970s when the brokerage industry was small and protected by tough legal restrictions on entry, antitrust policy frowned on vertical and horizontal growth (maybe), and a volatile macroeconomic environment encouraged internalization of inter-firm transactions (also maybe). After the brokerage industry was deregulated in 1975, the antitrust environment became more relaxed, and the market for corporate control heated up, many conglomerates were restructured into more efficient, specialized firms. To quote myself:

The investment community in the 1960s has been described as a small, close-knit group wherein competition was minimal and peer influence strong (Bernstein, 1992). As Bhide (1990, p. 76) puts it, “internal capital markets … may well have possessed a significant edge because the external markets were not highly developed. In those days, one’s success on Wall Street reportedly depended far more on personal connections than analytical prowess.” When capital markets became more competitive in the 1970s, the relative importance of internal capital markets fell. “This competitive process has resulted in a significant increase in the ability of our external capital markets to monitor corporate performance and allocate resources” (Bhide, 1990, p. 77). As the cost of external finance has fallen, firms have tended to rely less on internal finance, and thus the value added from internal-capital-market allocation has fallen. . . .

Similarly, corporate refocusing can be explained as a consequence of the rise of takeover by tender offer rather than proxy contest, the emergence of new financial techniques and instruments like leveraged buyouts and high-yield bonds, and the appearance of takeover and breakup specialists like Kohlberg Kravis Roberts, which themselves performed many functions of the conglomerate headquarters (Williamson, 1992). A related literature looks at the relative importance of internal capital markets in developing economies, where external capital markets are limited (Khanna and Palepu 1999, 2000).

The key reference is to Amar Bhide’s 1990 article “Reversing Corporate Diversification,” which deserves to be better known. But note also the pointer to Khanna and Palepu’s important work on diversified business groups in emerging markets, which has also led to a vibrant empirical literature. The idea there is that weak institutions lead to poorly performing capital and labor markets, leading firms to internalize functions that would otherwise be performed between firms. More generally, firm strategy and organization varies systematically with the institutional environment, both over time and across countries and regions.

Surprisingly, diversified business groups were also common in the US, in the early 20th century, which brings me (finally) to the point of this post. A new NBER paper by Eugene Kandel, Konstantin Kosenko, Randall Morck, and Yishay Yafeh studies these groups and reaches some interesting and provocative conclusions. Check it out:

Eugene Kandel, Konstantin Kosenko, Randall Morck, Yishay Yafeh

NBER Working Paper No. 19691, December 2013The extent to which business groups ever existed in the United States and, if they did exist, the reasons for their disappearance are poorly understood. In this paper we use hitherto unexplored historical sources to construct a comprehensive data set to address this issue. We find that (1) business groups, often organized as pyramids, existed at least as early as the turn of the twentieth century and became a common corporate form in the 1930s and 1940s, mostly in public utilities (e.g., electricity, gas and transportation) but also in manufacturing; (2) In contrast with modern business groups in emerging markets that are typically diversified and tightly controlled, many US groups were focused in a single sector and controlled by apex firms with dispersed ownership; (3) The disappearance of US business groups was largely complete only in 1950, about 15 years after the major anti-group policy measures of the mid-1930s; (4) Chronologically, the demise of business groups preceded the emergence of conglomerates in the United States by about two decades and the sharp increase in stock market valuation by about a decade, so that a causal link between these events is hard to establish, although there may well be a connection between them. We conclude that the prevalence of business groups is not inconsistent with high levels of investor protection; that US corporate ownership as we know it today evolved gradually over several decades; and that policy makers should not expect policies that restrict business groups to have an immediate effect on corporate ownership.

Easy Money and Asset Bubbles

| Peter Klein |

Central to the “Austrian” understanding of business cycles is the idea that monetary expansion — in Wicksellian terms, money printing that pushes interest rates below their “natural” levels — leads to overinvestment in long-term, capital-intensive projects and long-lived, durable assets (and underinvestment in other types of projects, hence the more general term “malinvestment”). As one example, Austrians interpret asset price bubbles — such as the US housing price bubble of the 1990s and 2000s, the tech bubble of the 1990s, the farmland bubble that may now be going on — as the result, at least partly, of loose monetary policy coming from the central bank. In contrast, some financial economists, such as Laureate Fama, deny that bubbles exist (or can even be defined), while others, such as Laureate Shiller, see bubbles as endemic but unrelated to government policy, resulting simply from irrationality on the part of market participants.

Michael Bordo and John Landon-Lane have released two new working papers on monetary policy and asset price bubbles, “Does Expansionary Monetary Policy Cause Asset Price Booms; Some Historical and Empirical Evidence,” and “What Explains House Price Booms?: History and Empirical Evidence.” (Both are gated by NBER, unfortunately, but there may be ungated copies floating around.) These are technical, time-series econometrics papers, but in both cases, the conclusions are straightforward: easy money is a main cause of asset price bubbles. Other factors are also important, particularly regarding the recent US housing bubble (I suspect that housing regulation shows up in their residual terms), but the link between monetary policy and bubbles is very clear. To be sure, Bordo and Landon-Lane don’t define easy money in exactly the Austrian-Wicksellian way, which references natural rates (the rates that reflect the time preferences of borrowers and savers), but as interest rates below (or money growth rates above) the targets set by policymakers. Still, the general recognition that bubbles are not random, or endogenous to financial markets, but connected to specific government policies designed to stimulate the economy, is a very important result that will hopefully influence current economic policy debates.

Recent Comments