Posts filed under ‘Business/Economic History’

Symposium on Allen’s Institutional Revolution

| Peter Klein |

Here is a symposium on Doug Allen’s very important book The Institutional Revolution (Chicago, 2011). The symposium features essays by Deirdre McCloskey, Joel Mokyr and José-Antonio Espín-Sánchez, and our own Dick Langlois, along with a reply by Doug. The issue revolves around the role of measurement, and Doug’s thesis that reductions in measurement costs are central to improved economic performance.

My favorite line, from Doug’s reply:

I have read “The Problem of Social Cost” more times than I can recall, and study as I may, I have never found a logical error in it. But here is the point: if the author, both at the time and 30 years later, still failed to fully grasp his own perfect work, then it is an understatement to note that the ideas are subtle.

David Landes

| Dick Langlois |

As some readers may already have heard, David Landes passed away on August 17. The New York Times has not seen fit to publish an obituary, but here is one by Landes’s son Richard.

I only met Landes once, at the International Economic History Association meeting in Milan in 1994. I attended a session he chaired on the Industrial Revolution. Rondo Cameron, a real character, sat himself down in the front row near the podium. Cameron was one of the most vocal proponents of the idea that there was actually no such thing as the Industrial Revolution, based largely on the argument that income per capita did not rise dramatically during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century (even though both the numerator and denominator were rising dramatically). Landes opened the session, and some hapless economic historian began presenting a paper on something or other during the Industrial Revolution. Cameron immediately put up his hand and announced that the presenter’s premise was mistaken – because there had been no Industrial Revolution! Landes then sprang back to the podium and delivered a wonderful extemporaneous speech on why it was indeed appropriate to talk about an Industrial Revolution, including an analysis of the word “revolution” and its first use in French. This session also sticks in memory because half-way through an audience member suffered and epileptic fit and had to be carted out to an ambulance.

I must say that, in the great debates in which Landes engaged, I most often found myself coming down on his side.

Addendum September 8, 2103: The New York Times now has an obituary here.

David Landes

| Dick Langlois |

As some readers may already have heard, David Landes passed away on August 17. The New York Times has not seen fit to publish an obituary, but here is one by Landes’s son Richard.

I only met Landes once, at the International Economic History Association meeting in Milan in 1994. I attended a session he chaired on the Industrial Revolution. Rondo Cameron, a real character, sat himself down in the front row near the podium. Cameron was one of the most vocal proponents of the idea that there was actually no such thing as the Industrial Revolution, based largely on the argument that income per capita did not rise dramatically during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century (even though both the numerator and denominator were rising dramatically). Landes opened the session, and some hapless economic historian began presenting a paper on something or other during the Industrial Revolution. Cameron immediately put up his hand and announced that the presenter’s premise was mistaken – because there had been no Industrial Revolution! Landes then sprang back to the podium and delivered a wonderful extemporaneous speech on why it was indeed appropriate to talk about an Industrial Revolution, including an analysis of the word “revolution” and its first use in French. This session also sticks in memory because half-way through an audience member suffered and epileptic fit and had to be carted out to an ambulance.

I must say that, in the great debates in which Landes engaged, I most often found myself coming down on his side.

Organizational Learning without Markets

| Peter Klein |

A really interesting NBER paper from Thomas Triebs and Justin Tumlinson confirms what you may suspect, that firms operating outside the market system — in this case, in the former East Germany — do not learn the capabilities for judging market signals. Triebs and Tumlinson compare East and West German firms after unification and find that East German firms did not anticipate, or respond to, market information as well as their West German counterparts, other things equal, suggesting that during the Communist period, firms lost (or failed to acquire) the ability to work within a market setting. The paper is based on a formal learning model but the empirical results seem to square with a variety of approaches, including resource-based and managerial capabilities theories.

Learning Capitalism the Hard Way—Evidence from Germany’s Reunification

Thomas P. Triebs, Justin Tumlinson

NBER Working Paper No. 19209, July 2013Communism in East Germany sought to dampen the effect of market forces on firm productivity for nearly 40 years. How did East German firms respond to the free market after being thrust into it in 1990? We use a formal learning model and German business survey data to analyze the lasting impact of this far-reaching treatment on the way firms in former East Germany predicted their own productivity relative to firms in former West Germany during the two decades since Reunification. We find in confirmation of our formal model’s predictions, that Eastern firms forecast productivity less accurately, particularly in dynamic and uncertain markets, but that the gap gradually closed over 12 to 13 years. Second, by analyzing the direction of firm level errors in conjunction with contemporaneous market signals we find that, in the years immediately following Reunification, Eastern firms estimate the market’s role as generally less potent than Western firm do, an observation consistent with overweighting experiences from the communist era; however, over roughly 14 years both converge to the same (incorrect) overestimate of the market’s role on their productivity.

I’m reminded of Mises’s remark that entrepreneurs, in a socialist economy, learn to excel at “diplomacy and bribery.” I suspect a study like Triebs and Tumlinson’s on political capabilities or skill at political entrepreneurship might yield the opposite result.

Mokyr on Cultural Entrepreneurship

| Peter Klein |

I am wary of adding yet another conceptual margin for entrepreneurial action but I highly recommend a new (and for the moment, ungated) paper in the Scandinavian Economic History Review by the distinguished economic historian Joel Mokyr on “cultural entrepreneurship.” Starting from a broadly Schumpeterian perspective, Mokyr focuses on individuals who introduce and disseminate novel ideas:

[E]ach individual makes cultural choices taking as given what others believe. It is not a priori obvious how that affects one’s choices. It may affect them positively because conformism implies that there is some social cost associated with deviancy, or because people may reason that if the majority believes a certain thing, there may be wisdom in it (thus saving on information costs). But there can be a reverse reaction as well, with non-conformists perversely rebelling against existing beliefs. What matters for my purposes is that for a small number of individuals, the beliefs of others are not given but can be changed. I shall refer to those people as cultural entrepreneurs. Their function is much like entrepreneurs in the realm of production: individuals who refuse to take the existing technology or market structure as given and try to change it and, of course, benefit personally in the process. Much like other entrepreneurs, the vast bulk of them make fairly marginal changes in our cultural menus, but a few stand out as having affected them in substantial and palpable ways.

Succinctly expressed: “cultural entrepreneurs are the creators of epistemic focal points that people can coordinate their beliefs on.”

Mokyr’s focus, like Schumpeter’s, is not entrepreneurship per se, but its effects, particularly on long-run economic growth, and his entrepreneurship construct is somewhat undertheorized. But he provides fascinating examples, ranging from Mohammed and Luther to Francis Bacon, Isaac Newton, and Adam Smith. He focuses in particular on Bacon and Newton, describing Bacon’s work as “the coordination device which served as the point of departure for thinkers and experimentalists for two centuries to come. The economic effects of these changes remained latent and subterranean for many decades, but eventually they erupted in the Industrial Revolution and the subsequent processes of technological change.” Newton and the Royal Society “raise[d] the social standing of scientists and researchers as people who should be respected and supported and [provided] them with a comfortable material existence.” (Mostly good.)

I’m not an expert on cultural theory or history and am not sure how much the “cultural entrepreneur” construct ads to our understanding of cultural change (other than relabeling, a frequent worry in entrepreneurship studies). But the paper is a great read, highly provocative and informative, and addresses big questions. Check it out.

Keynes in the Spotlight

| Peter Klein |

As the Niall Ferguson kerfuffle begins fading from memory it’s worth revisiting the underlying issue: What kind of person was John Maynard Keynes, and (how) did his social, cultural, moral, and aesthetic views affect his scientific work?

As the Niall Ferguson kerfuffle begins fading from memory it’s worth revisiting the underlying issue: What kind of person was John Maynard Keynes, and (how) did his social, cultural, moral, and aesthetic views affect his scientific work?

Here are a few recommended readings:

- Ralph Raico, “Was Keynes a Liberal?” (Independent Review, 2008)

- Schumpeter’s obituary of Keynes (AER, 1946)

- Murray Rothbard, “Keynes the Man” (in Dissent on Keynes, 1992)

These works are not kind to ole’ John Maynard (I’m posting them, what did you expect?). Rothbard, for example, emphasizes Keynes’s “overweening egotism, which assured him that he could handle all intellectual problems quickly and accurately and led him to scorn any general principles that might curb his unbridled ego,” also referring to Keynes’s “deep hatred and contempt for the values and virtues of the bourgeoisie,” including savings and thrift. It’s hard to imagine that Keynes’s personal views on thrift could be unrelated to the now-ubiquitous, über-Keynesian idea that spending, not savings and capital accumulation, is the driver of economic growth.

On time preference, and its social and cultural causes and consequences, I recommend Time and Public Policy by T. Alexander Smith (University of Tennessee Press, 1988), which unfortunately appears to be out of print. Here is a brief review by Israel Kirzner.

AMP Symposium on Private Equity

| Peter Klein |

The new issue of the Academy of Management Perspectives features a symposium, edited by Mike Wright, on “Private Equity: Managerial and Policy Implications.” The symposium includes “Private Equity, HRM, and Employment” by Mike with Nick Bacon, Rod Ball, and Miguel Meuleman; “The Evolution and Strategic Positioning of Private Equity Firms” by Robert E. Hoskisson, Wei Shi, Xiwei Yi, and Jing Jin; and “Private Equity and Entrepreneurial Governance: Time for a Balanced View” by John L. Chapman, Mario P. Mondelli, and me. The symposium came out very nicely, if I may say so, covering a variety of strategic, entrepreneurial, and organizational issues related to private equity firms and companies receiving private equity finance.

In his introduction Mike highlights five main contributions:

First, the papers address the need to consider the systematic evidence on the managerial and strategic aspects of PE, in relation to both portfolio firms and PE firms, which has been largely fragmented if not nonexistent. Second, the papers analyze the impact of PE during economic downturns and demonstrate the underlying resilience of PE-backed portfolio firms. Third, the symposium provides an opportunity to develop insights that compare the managerial impact of PE with different forms of ownership and governance. Fourth, the articles in this symposium highlight the heterogeneity of the private equity phenomenon. Finally, in the context of continuing public attention to PE, which has been heightened by the U.S. presidential race and the global recession, the evidence presented in this symposium paints a rather more positive view than the hyperbole of some of the industry’s critics would suggest. Taken together, these contributions indicate a need for caution in attempts to tighten the regulation of PE lest the economic, financial, and social benefits be lost.

Blanchard on Fed Independence

| Peter Klein |

I’ve argued before (1, 2) that the usual arguments for central bank independence aren’t very strong, particularly in the current environment where Bernanke has interpreted the “unusual and exigent circumstances” provision to mean “I will do whatever I want.” (This was a major point in my Congressional testimony about the Fed.) So it was nice to see Olivier Blanchard express similar reservations in an interview published in today’s WSJ (I assume it’s not an April Fool’s Day prank):

One of the major achievements of the last 20 years is that most central banks have become independent of elected governments. Independence was given because the mandate and the tools were very clear. The mandate was primarily inflation, which can be observed over time. The tool was some short-term interest rate that could be used by the central bank to try to achieve the inflation target. In this case, you can give some independence to the institution in charge of this because the objective is perfectly well defined, and everybody can basically observe how well the central bank does..

If you think now of central banks as having a much larger set of responsibilities and a much larger set of tools, then the issue of central bank independence becomes much more difficult. Do you actually want to give the central bank the independence to choose loan-to-value ratios without any supervision from the political process. Isn’t this going to lead to a democratic deficit in a way in which the central bank becomes too powerful? I’m sure there are ways out. Perhaps there could be independence with respect to some dimensions of monetary policy - the traditional ones — and some supervision for the rest or some interaction with a political process.

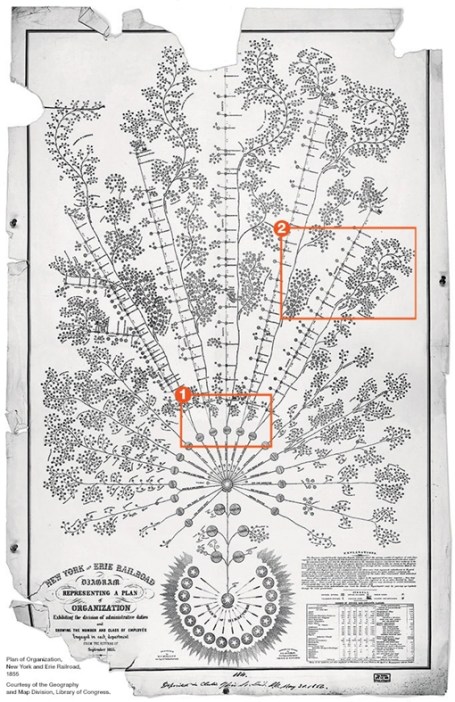

The First Modern Organizational Chart

| Peter Klein |

It was designed in 1854 for the New York and Erie Railroad and reflects a highly decentralized structure, with operational decisions concentrated at the local level. McKinsey’s Caitlin Rosenthal describes it as an early attempt to grapple with “big data,” one of today’s favored buzzwords. See her article, “Big Data in the Age of the Telegraph,” for a fascinating discussion. And remember, there’s little new under the sun (1, 2, 3).

The Myth of the Flattening Hierarchy

| Peter Klein |

We’ve written many posts on the popular belief that information technology, globalization, deregulation, and the like have rendered the corporate hierarchy obsolete, or at least led to a substantial “flattening” of the modern corporation (see the links here). The theory is all wrong — these environmental changes affect the costs of both internal and external governance, and the net effect on firm size and structure are ambiguous — and the data don’t support a general trend toward smaller and flatter firms.

Julie Wulf has a paper in the Fall 2012 California Management Review summarizing her careful and detailed empirical work on the shape of corporate hierarchies. (The published version is paywalled, but here is a free version.) Writes Julie:

I set out to investigate the flattening phenomenon using a variety of methods, including quantitative analysis of large datasets and more qualitative research in the field involving executive interviews and a survey on executive time use. . . .

We discovered that flattening has occurred, but it is not what it is widely assumed to be. In line with the conventional view of flattening, we find that CEOs eliminated layers in the management ranks, broadened their spans of control, and changed pay structures in ways suggesting some decisions were in fact delegated to lower levels. But, using multiple methods of analysis, we find other evidence sharply at odds with the prevailing view of flattening. In fact, flattened firms exhibited more control and decision-making at the top. Not only did CEOs centralize more functions, such that a greater number of functional managers (e.g., CFO, Chief Human Resource Officer, CIO) reported directly to them; firms also paid lower-level division managers less when functional managers joined the top team, suggesting more decisions at the top. Furthermore, CEOs report in interviews that they flattened to “get closer to the businesses” and become more involved, not less, in internal operations. Finally, our analysis of CEO time use indicates that CEOs of flattened firms allocate more time to internal interactions. Taken together, the evidence suggests that flattening transferred some decision rights from lower-level division managers to functional managers at the top. And flattening is associated with increased CEO involvement with direct reports —the second level of top management—suggesting a more hands-on CEO at the pinnacle of the hierarchy.

As they say, read the whole thing.

Creative Destruction Chart of the Day

| Peter Klein |

Via John Hagel, a chart from Mary Meeker showing the percent of personal computing devices (including, today, phones and tablets) accessing the web from various operating systems. Joseph Schumpeter, call your office!

More Genghis Revisionism

| Peter Klein |

You’ve probably heard the expression, “X is so extreme, he’s to the Right of Genghis Khan.” This basically means, “I don’t like X but have nothing intelligent to say about X or his ideas.” Mostly because we don’t know much about Genghis Khan, and what we do know presents a pretty complex picture. I mentioned before Jack Weatherford’s revisionist portrayal of the Great Khan as a somewhat progressive ruler, by the standards of his time. Now I learn, from Joe Salerno, about a paper by Andrius Valevicius “arguing that Genghis Khan’s successful empire building lay in his introduction of low taxes, stamping out of torture, and promotion of religious toleration and diversity and free scholarly inquiry in the conquered territories. The Great Khan also restricted his plundering to the wealth and property of the vanquished ruling elites while leaving their subjects generally unmolested in their persons and property and even distributing some of the plunder among them.”

You’ve probably heard the expression, “X is so extreme, he’s to the Right of Genghis Khan.” This basically means, “I don’t like X but have nothing intelligent to say about X or his ideas.” Mostly because we don’t know much about Genghis Khan, and what we do know presents a pretty complex picture. I mentioned before Jack Weatherford’s revisionist portrayal of the Great Khan as a somewhat progressive ruler, by the standards of his time. Now I learn, from Joe Salerno, about a paper by Andrius Valevicius “arguing that Genghis Khan’s successful empire building lay in his introduction of low taxes, stamping out of torture, and promotion of religious toleration and diversity and free scholarly inquiry in the conquered territories. The Great Khan also restricted his plundering to the wealth and property of the vanquished ruling elites while leaving their subjects generally unmolested in their persons and property and even distributing some of the plunder among them.”

Don’t Fear the Reaper

| Peter Klein |

An important contribution to the history of technology and the relationship between technology, organization, and strategy:

Gordon Winder’s The American Reaper is a solid and significant contribution to the history of American grain harvesting implements. Winder offers several revisionist challenges to standard accounts, both those that have treated Cyrus McCormick as a heroic inventor, as well as those that have touted the International Harvester Corporation (IHC, formed in 1902) as a path-breaking model of a vertically integrated and internationally dominant firm. . . . Reaper manufacturers forged licensing agreements, subcontracted with suppliers and branch factories, shared expert personnel and innovations, hired widely dispersed sales agents, and formed alliances to protect patent advantages in order to remain competitive.

Read the rest of the EH.Net review here.

Tom McCraw

| Dick Langlois |

I was saddened to hear today of the passing of Tom McCraw at the young age of 72. I didn’t always agree with him: he was a strong admirer of the Progressives, and even tried implausibly to suggest in Prophet of Innovation, his great biography of Schumpeter, that Schumpeter would have agreed with Progressive policies had he been alive today. But McCraw was a gentleman, a fine writer, and an important figure in business history. Prophet of Innovation is a terrific book. I wish I had written it.

Henry Manne at Missouri, on the Crisis in Higher Education

| Peter Klein |

Missouri friends, please join us next Tuesday for a lecture by Henry Manne on the governance and organization of US higher education institutions:

The Crisis in Higher Education:

Origins and Problems of University Governance

Henry G. Manne

Dean Emeritus, George Mason University Law School

Tuesday, October 23, 2012, 3:30-4:45pm

MU Student Center, Room 2206

University of Missouri

Sponsored by the Liberty and Justice Colloquium, University of Missouri

Free and Open to the Public

Henry G. Manne is Dean Emeritus of the George Mason School of Law and an expert on insider trading, legal education, university governance, and law and economics. He has also taught at St. Louis University, the University of Wisconsin, George Washington University, the University of Rochester, Stanford University, the University of Miami, Emory University, the University of Chicago, and Northwestern University.

Dean Manne is an Honorary Life Member of the American Law and Economics Association, which honored him as one of the four founders of the field of Law and Economics. He launched the Law and Economics Center at Emory University and the University of Miami before bringing it to George Mason University. His monograph, An Intellectual History of the School of Law, George Mason University, traces the development of the law and economics.

Dean Manne’s other writings include such seminal works as Insider Trading and the Stock Market, Wall Street in Transition (with E. Solomon), and “Mergers and the Market for Corporate Control” Journal of Political Economy, 1965). He is also a frequent contributor to the Wall Street Journal. In 1999, the Case Western Reserve Law Review published the papers from a symposium honoring the many contributions of Dean Manne to the law and economics movement as The Legacy of Henry G. Manne. The Liberty Fund recently published The Collected Works of Henry G. Manne in three volumes.

Dean Manne holds a B.A. from Vanderbilt University (1950), J.D. from the University of Chicago (1952), J.S.D. from Yale University (1966), LL.D. from Seattle University (1987), and LL.D. from the Universidad Francesco Marroquin in Guatemala (1987).

Obama on Small Business

| Peter Klein |

President Obama’s gaffe about business creation — “If you’ve got a business, you didn’t build that. Somebody else made that happen” — has been met with the usual reactions. Defenders claim he simply used infelicitous language to describe the vital role of government in providing essential goods, while critics point out, for instance, that he didn’t even get it right on the Golden Gate Bridge (which received no federal money). I actually feel sorry for the guy. It was an pretty dumb thing to say, politically, and may end up hurting him more than Romney’s role in “exporting American jobs” (gag) hurts the challenger.

President Obama’s gaffe about business creation — “If you’ve got a business, you didn’t build that. Somebody else made that happen” — has been met with the usual reactions. Defenders claim he simply used infelicitous language to describe the vital role of government in providing essential goods, while critics point out, for instance, that he didn’t even get it right on the Golden Gate Bridge (which received no federal money). I actually feel sorry for the guy. It was an pretty dumb thing to say, politically, and may end up hurting him more than Romney’s role in “exporting American jobs” (gag) hurts the challenger.

The idea that no one builds a business on his own, without help from other people, is in once sense trivially true, as Leonard Read never tired of explaining. No one person knows how to make a pencil, let alone a microprocessor. As a defense of government spending on infrastructure (not only roads and bridges, but things like the internet), it falls completely flat. Of course some entrepreneurs profit from government spending on infrastructure — not just directly (e.g., road contractors, engineering companies hired by ARPA, etc.) but indirectly (from lower transportation or transmission cost, net of tax payments). But such anecdotes do not at all “justify” the expenditures. As I once wrote about the internet:

[E]nthusiasts tend to forget the fallacy of the broken window. We see the internet. We see its uses. We see the benefits it brings. We surf the web and check our email and download our music. But we will never see the technologies that weren’t developed because the resources that would have been used to develop them were confiscated by the Defense Department and given to Stanford engineers. Likewise, I may admire the majesty and grandeur of an Egyptian pyramid, a TVA dam, or a Saturn V rocket, but it doesn’t follow that I think they should have been created, let alone at taxpayer expense.

A gross benefit to particular entrepreneurs from a government program does not, by itself, demonstrate net benefits to the taxpaying community. Vague references to spillovers and multipliers may sound good in a press conference, but are no substitute for serious analysis.

Entrepreneurship and the Auteur Theory

| Peter Klein |

I’ve been reading Jack Mathews’ The Battle of Brazil: Terry Gilliam v. Universal Pictures in the Fight to the Final Cut, a fascinating — if absurdly one-sided — look at director Terry Gilliam’s struggle to get his 1985 film Brazil distributed in the US. Mathews tells the story as a noble crusade by a brilliant, iconoclastic, visionary filmmaker against the evil studio system, run by corporate toadies who care only about making money, even if it means destroying the artistic unity of the filmmaker’s creative vision. Gilliam had “final cut” rights for a version released in Europe, but his US distributor, Universal, demanded substantial edits, which Gilliam refused to make. Universal, led by Sid Sheinberg (who comes across heroically in documentaries about Steven Spielberg’s Jaws), was completely within its contractual rights to insist on these changes, but the result was a very different film that has been lampooned by critics. (The Sheinberg version was canned and an alternate Gilliam version eventually shown in the US after a long, ugly, public battle between Gilliam and the studio.)

I’ve been reading Jack Mathews’ The Battle of Brazil: Terry Gilliam v. Universal Pictures in the Fight to the Final Cut, a fascinating — if absurdly one-sided — look at director Terry Gilliam’s struggle to get his 1985 film Brazil distributed in the US. Mathews tells the story as a noble crusade by a brilliant, iconoclastic, visionary filmmaker against the evil studio system, run by corporate toadies who care only about making money, even if it means destroying the artistic unity of the filmmaker’s creative vision. Gilliam had “final cut” rights for a version released in Europe, but his US distributor, Universal, demanded substantial edits, which Gilliam refused to make. Universal, led by Sid Sheinberg (who comes across heroically in documentaries about Steven Spielberg’s Jaws), was completely within its contractual rights to insist on these changes, but the result was a very different film that has been lampooned by critics. (The Sheinberg version was canned and an alternate Gilliam version eventually shown in the US after a long, ugly, public battle between Gilliam and the studio.)

It’s great reading for those interested in movies and the business of making movies. But there’s an interesting entrepreneurship angle as well. Most film critics, including author Mathews, accept the auteur theory of cinema, which sees movies as the highly personal products of a director’s creative vision. The studio approach, which treats moviemaking as a collaborative enterprise designed to make money, is anathema to the auteurs. The case is usually made with familiar anecdotes: 24-year-old Orson Welles had final control over Citizen Kane and created one of the medium’s great masterpieces, while RKO destroyed the follow-up Magnificent Ambersons (and all Welles’s subsequent films). The studios thought Star Wars would flop, and after George Lucas made his zillions he decided to finance and produce his subsequent films on his own, without studio interference — the dream of every auteur. American art-house darlings like Robert Altman, Peter Bogdonavich, Quentin Tarantino, Jim Jarmusch, etc. are always portrayed as fighting to keep Hollywood from turning their edgy, original films into bland, corporate drivel pitched at suburban soccer moms.

As Paul Cantor and others have explained, however, the auteur theory is bunk. Moviemaking is, in fact, a collaborative venture, and many of the best films are studio pictures created by large teams — the best example being Casablanca, which was essentially written by committee. Or, as Cantor puts it: “Just three words: Francis Ford Coppola.” (The Godfather films were studio pictures; virtually everything Coppola did since, with the partial exception of Apocalypse Now, has been a disaster.) And take George Lucas: Does anybody think the problem with the prequel trilogy was too many people standing around saying, “George, you can’t do that”?

Consider the parallels with entrepreneurship. (more…)

Lewin on Austrian Capital Theory

| Peter Klein |

A very nice overview of “Austrian” capital theory and its relevance for the current economic crisis from former guest blogger Peter Lewin.

With the resurgence of Keynesian economic policy as a response to the current crisis, echoes of past debates are being heard — in particular the debate from the 1930s between John Maynard Keynes and Friedrich Hayek. . . . Hayek pointed out that capital investment does not simply add to production in a general way but rather is embodied in concrete capital items. That is, the productive capital of the economy is not simply an amorphous “stock” of generalized production power; it is an intricate structure of specific interrelated complementary components. Stimulating spending and investment, then, amounts to stimulating specific sections and components of this intricate structure.

See also the recent SO!APbox essay by Rajshree Agarwal, Jay Barney, Nicolai, and me, “Heterogeneous Resources and the Financial Crisis: Implications of Strategic Management Theory.”

The Socialist Car

| Peter Klein |

| Peter Klein |

I blogged previously about Lewis Siegelbaum’s 2008 book Cars for Comrades: The Life of the Soviet Automobile (or, more precisely, Perry Patterson’s EH.Net review). So I need to say something about the follow up, The Socialist Car: Automobility in the Eastern Bloc (Cornell University Press, 2011), an essay collection edited by Siegelbaum. Once again, here’s Patterson:

As was true for Cars for Comrades, this book takes the modern upper-middle-class Western reader far from the contemporary world where drivers need not know what’s “under the hood,” where synthetic oil might not need attention for 15,000 miles or more, and where long-standing institutions for finance, distribution and service of vehicles are seemingly ubiquitous. Rather, this is a world where two-stroke engines are designed for easy (and frequent) self-service, new car owners are required to install windshield wipers, and new automobiles are provided with extensive repair kits and instructions for disassembly. This world is also one where private automobiles – and even socially-owned trucks – represent potential threats to the Soviet-style socialist undertaking by providing opportunities for generating illegal incomes and diverting resources toward consumption. At the core of the rich set of stories contained here are the compromises that everyday citizens, urban planners, and Party officials routinely made as the powerful forces associated with the automobile became more and more apparent throughout the socialist bloc. In addition, the examples presented in this eleven-chapter volume say much about the increasingly complex information flows required and implied by automobiles that became more and more technically complex over time.

Speaking of EH.net, the performativity crowd may get a kick out of another recent review, Bruce Carruthers’s discussion of Carl Wennerlind, Casualties of Credit: The English Financial Revolution, 1620-1720 (Harvard University Press, 2011). Notes Carruthers: “It was not simply that early modern capital markets evolved, that financial systems developed, or that English economic institutions changed. These critical transformations were accompanied and even shaped by the analyses offered by people who witnessed the events of the time.”

Computers in Higher Education, 1960s Edition

| Peter Klein |

An illuminating passage from James Ridgeway’s 1968 book The Closed Corporation: American Universities in Crisis, a scathing critique of the university-military-industrial complex. Note the cameo by Jim March:

[University of California officials Ralph W.] Gerard and [R. Dan] Tschirgi are computer fetishists who insist information is knowledge, and that the function of a university is to provide information.

In 1963 and 1964 Chancellor David G. Aldrich, Jr., at Irvine, and Gerard got IBM interested in setting up programs there. The company agreed to install a 1400 system and to supply staff and engineers. An IBM employee, Dr. J. A. Kearns, came along to head the project and was given a part-time appointment at the Graduate School of Administration. The idea was to see whether the computer could be used as a library, for various administrative functions and for teaching.

Gerard paints a glowing picture. He says that one half of the students on the Irvine campus spend at least one hour a week on the computer, and that computers are used in teaching biology, mathematics, economics, sociology and psychology.

After speaking with Gerard, I went along to see the computer in action, and ran into a senior staff man who told me in a jaundiced manner that it wasn’t operating because they couldn’t make the new IBM 360 system work right. This gentleman was exceedingly glum about the possibilities of very many students learning much of anything on the Irvine computers. So was the dean of Social Sciences, James G. March. When I asked him about the use of the machine to teach sociology, he replied grimly that all the computer did was to print out some basic definitions in an introductory course, which, as he pointed out, one could get just as well from reading a book. He went on to say that a minute portion of any introductory course was on a computer, that students spent little time on them, and that most of the time was taken up programming them. March said the difficulty was to devise a system which could answer questions rather than ask them. The most one could really expect was to have a machine pose a problem to the student, who could then go ahead an answer it on his own.

The tech described here is dated but the book itself still packs a punch. In the late 1906s concerns about the close relationships between the federal government (particularly the Pentagon), public research universities, and industry (particularly defense contractors) were new. Now we take for granted that a primary task of the research university is to produce “applied” research in close cooperation with government and industry sponsors, to commercialize its scientific discoveries, to train students for industry, and so on. But this is a fairly recent — mid-20th century — development, and not an obviously desirable one.

Recent Comments