Posts filed under ‘Business/Economic History’

The Legacy and Work of Douglass North

| Peter Klein |

Washington University, St. Louis is hosting a major international conference, 4-6 November, on the Legacy and Work of Douglass North. The all-star panel includes Lee Alston, Robert Bates, Joel Mokyr, Elinor Ostrom, Ken Shepsle, Barry Weingast, and many others. The conference is organized by Wash U’s Center for New Institutional Social Science.

In other conference news, the CFP for next year’s Atlanta Competitive Advantage Conference, 17-19 May 2011, has been posted. Featured presenters include Jay Barney, Joel Baum, and Rebecca Henderson.

Two New Books on Economic Growth

| Dick Langlois |

In addition to the review of Doug Puffert’s book that Peter discusses in his most recent post, EH.net has also just issued reviews of two books on economic growth that should be of interest to O&M readers. One is of Michael Heller’s Capitalism, Institutions, and Economic Development. I hope this one gets wide circulation despite being an expensive Routledge title. The other is of Matt Ridley’s The Rational Optimist: How Prosperity Evolves. That one should get a lot of attention.

Lock-In, Path Dependence, and Efficiency: Railway Gauge Edition

| Peter Klein |

Doug Puffert’s new book on the history of railway gauge standardization apparently takes a middle position between the “lock-in always” position of Paul David and the “lock-in rarely” position of Liebowitz and Margolis. Writes reviewer Dan Bogart:

Doug Puffert’s new book on the history of railway gauge standardization apparently takes a middle position between the “lock-in always” position of Paul David and the “lock-in rarely” position of Liebowitz and Margolis. Writes reviewer Dan Bogart:

Puffert’s narrative convincingly dispels the extreme version of the Liebowitz and Margolis critique which argues that market participants had perfect foresight. On the other hand, it does suggest historical actors understood the role of positive feedbacks and tried to manipulate gauge adoption in an effort to lock-in their preferred standard. The degree to which gauge selection was efficient is a lingering question throughout the book. Puffert does not take a stand on the relative efficiency of different gauges, but an argument is made that diversity entailed large costs.

I’m not sure what Bogart means by the “extreme version” of the Liebowitz-Margolis critique; L&M have certainly never used the concept of perfect foresight in their analysis of alleged QWERTY effects. Indeed, their critique of Paul David is based mostly on comparative institutional analysis. As Peter Lewin puts it in his excellent summary of the QWERTY debate:

Somewhat paradoxically both Liebowitz and Margolis and their critics (in varying degrees) are critical of mainstream neoclassical (textbook) economics and its standards of welfare. That is to say, they are both highly critical of the kind of neoclassical economics that assumes perfect knowledge, perfect foresight, many traders, etc., the kind that derives perfect competition as a Pareto optimal efficient standard against which to judge real world outcomes. Both focus (to a greater or lesser extent) on the importance of ignorance and uncertainty (and the importance of institutions) in rendering such a standard problematic. Where they differ decisively, however, is in the policy lessons that they take away from this.

The critics argue that the ideal of perfect competition is an ideal that, for one reason or another, the free market is incapable of attaining, and that, therefore, one should look to the government to obtain by collective action or regulation, what the market, with decentralized actors, cannot. Liebowitz and Margolis have explained clearly why the endorsement of government intervention does not follow from a valid critique of neoclassical welfare economics (and, for that matter, why a defense of neoclassical welfare economics, in itself, is insufficient to establish an argument against intervention).

See here for a previous discussion on path dependence and Williamson’s “remediableness” criterion.

The (Very) Early Adoption of Modern HRM Practices

| Peter Klein |

Bruce Kaufman’s book Hired Hands or Human Resources? Case Studies of HRM Programs and Practices in Early American Industry (Cornell U. P., 2010) shows that US firms started adopting “modern” HRM practices around World War I, not during the New Deal, and they did so primarily to increase productivity, not in response to union or government pressure. Writes reviewer Chad Pearson:

Kaufman illustrates the ways in which several companies created professional human resource management (HRM) models after World War I. This is the most valuable part of the book principally because he used the records of the Industrial Relations Councilors (IRC), a consulting firm that began assisting employers in the 1910s. The IRC offered consulting services, provided research, and ran courses on industrial relations topics throughout the nation. Kaufman, the first scholar to examine these records, believes that “no other [industrial relations consulting firm] before World War II had IRC’s reach and influence” (p. 108). . . .

In most cases, these firms, in consultation with the IRC, began to, in Kaufman’s words, treat labor not as “a short-term commodity,” as was common in previous decades, but rather as “a longer-term human capital asset (the ‘human resource’ approach)” (p. 219). Why? Pressure from unions and the law were factors, but “they were less than half the story in the time period we are examining” (p. 228). In his view, employers’ desires to improve “management and productivity” better explain why companies improved workplace conditions (p. 227).

Labor historians and specialists in business regulation used to focus on the Progressive Era as a watershed period — e.g., Wiebe (1962), Weinstein (1981), and of course Kolko (1977) — but interest seems to have waned.

Elgar Companion to TCE

The Elgar Companion to Transaction Cost Economics, edited by Mike Sykuta and me, has just been published. Twenty-nine chapters cover the basic structure of TCE, its precursors and influences, fundamental concepts, applications and evidence, along with alternatives and critiques. Oliver Williamson was kind enough to contribute an introduction and overview. Co-blogger Foss is in there as well.

O&M readers can get it here 10 percent off the list price! (Actually, anybody can get the deal.) Mike beat me to the punch with an announcement and description, so I’ll just add that we’re really pleased with the final product and grateful to all the distinguished contributors and the production staff.

Here are previous O&M posts on transaction cost economics.

The Myth of the Razors-and-Blades Strategy

| Peter Klein |

| Peter Klein |

Not quite as exciting as the GM-Fisher contretemps, but in the same revisionist vein: Randy Picker’s new paper, “The Razors-and-Blades Myth(s).”

From 1904-1921, Gillette could have played razors-and-blades — low-price or free handles and expensive blades — but it did not do so. Gillette set a high price for its handle — high as measured by the price of competing razors and the prices of other contemporaneous goods — and fought to maintain those high prices during the life of the patents. For whatever it is worth, the firm understood to have invented razors-and-blades as a business strategy did not play that strategy at the point that it was best situated to do so.

Here’s a PPT version.

Well, as Bogey might have said to Bergman: “We’ll always have printer ink.”

An Industry Study for the Beautiful People

| Peter Klein |

It’s Beauty Imagined: A History of the Global Beauty Industry by Geoffrey Jones (Oxford University Press, 2010). From the blurb:

This book provides the first authoritative history of the global beauty industry from its emergence in the nineteenth century to the present day, exploring how today’s global giants grew. It shows how successive generations of entrepreneurs built brands which shaped perceptions of beauty, and the business organizations needed to market them. They democratized access to beauty products, once the privilege of elites, but they also defined the gender and ethnic borders of beauty, and its association with a handful of cities, notably Paris and later New York. The result was a homogenization of beauty ideals throughout the world.

Sounds like a great study of entrepreneurship, industry dynamics, clustering and network effects, and the relationship between business and culture. Reviewer Ingrid Giertz-Mårtenson says it’s “one of the more fascinating stories in modern business history,” the journey of an industry once seen as “fickle, superficial, and feminine” to a “brand-driven global power house.” The book should make a beautiful addition to your collection!

Texting Victorians

| Peter Klein |

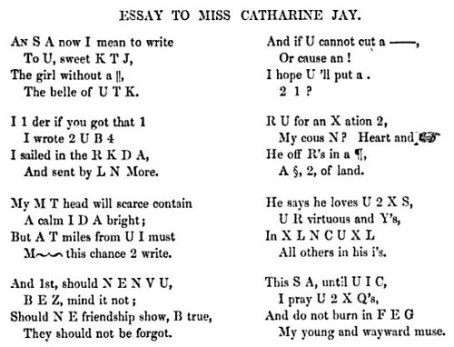

I knew that the Victorians had their own Internet, that information goods and open innovation are old hat, and that S-curves go back a hundred years. But apparently the Victorians used texting language too! We instruct our students to avoid it, but apparently Victorian poets thought writing I “love U 2 X S” or “U R virtuous and Y’s” was exceedingly clever. LOL! (Discovery! via Gizmodo.)

The (Very) Early History of Financial Economics

| Peter Klein |

The latest issue of the History of Economics Review contains Geoffrey Poitras and Jovanovic’s interesting paper, “Pioneers of Financial Economics: Das Adam Smith Irrelevanzproblem?” (published version not available online; working-paper version here, presentation slides here). Despite the subtitle the paper isn’t about Adam Smith, but the (very) early history of financial economics. Here’s an excerpt:

In the case of financial economics, the roots of this field stretch back to antiquity, involving the valuation of financial transactions, such as determining payment on a loan or distributing profits from a partnership. Poitras (2000) uses the late fifteenth century as a starting point for the early or pre-classical history of financial economics, more than three centuries prior to the publication of the [Wealth of Nations]. As early as Fibonacci (1170?-1250?), elements of financial economics were being disseminated among the merchant classes in the commercial arithmetics that, by the fifteenth century, formed the core of the reckoning school curriculum, e.g., Swetz (1987). A fundamental historical demarcation point appears with Christian Huygens’s (1629-1695) seminal introduction of the modern theory of expectations.

From this point, until the appearance of the WN, the founding work of classical political economy, financial economics underwent a dramatic transformation. By the time the Theory of Moral Sentiments appeared, sophisticated methods for pricing contingent claims, such as the life annuities sold by various individuals, municipalities and national governments in western Europe, had been developed and were being applied to the establishment of actuarially sound life insurance plans and pension funds. Hald (1990), Poitras (2006), Lewin (2003) and Rubinstein (2003) among others identify the earliest pioneers of modern financial economics, the beginning of classical financial economics, from the contributors that developed these pricing methods. As such, there is a close connection between the classical histories of financial economics, statistics, and actuarial science.

In other words, this is a field in which theory and practice appear to have co-evolved quite closely, which raises interesting questions for the performativity crowd. Modern financial economics is in many ways similar: theories of market efficiency were both shaped by, and helped to shape (e.g., through options-pricing formulas) actual market behavior.

Add to: Facebook | Digg | Del.icio.us | Stumbleupon | Reddit | Blinklist | Twitter | Technorati

The Noir Institutional Economics

| Dick Langlois |

The Visible Hand

By Raymond Chandler

It was eight o’clock in the morning, sharp, with the sun not shining and a look of hard wet rain on the Manhattan pavement. I was wearing my heavy gray flannel suit, with rounded collar, display handkerchief, and gold tie with streamlined mechanical shapes on it. As always, I was neat, clean, shaved and sober, and I didn’t care who knew it. I was everything the well-dressed professional manager ought to be. I was calling on the head of General Motors.

From two blocks away I stared at the GM building at 57th and Broadway, its terra cotta façade now etched gray as the pavement, as it wrapped itself around the gothic fantasy of the Broadway Tabernacle at 56th Street. I knew which one was really the cathedral. I didn’t get to inspect the building’s interior for as long as I had the outside. The minute I walked through the front door I was met by a tall, striking female, platinum blonde in finger waves. She wore a cardigan jacket over a skirt and sweater. Her eyes were slate-gray, and had almost no expression when they looked at me.

“Mr. Sloan?”

I admitted as much.

“Follow me, please.”

Following her was easy. She led me into a black-and-gilt elevator. Like all New York elevator men, the operator was small and pinched but looked as though he knew something we didn’t. He brought us up to the top floor, where the cast iron grille of the elevator opened onto an anteroom of the inner-sanctum. When I glanced back, the blonde had already disappeared. I walked in. (more…)

Rothbard Quote of the Day: Theory and History

| Peter Klein |

I stumbled recently upon this passage from Murray Rothbard’s review of Unemployment in History by the distinguished historian John A. Garraty. Rothbard’s review, published in 1978, raised an issue that has come up in previous discussions of the Freakonomics phenomenon (1, 2, 3, 4): Can a little theory, without accompanying real-world knowledge, be a dangerous thing?

I stumbled recently upon this passage from Murray Rothbard’s review of Unemployment in History by the distinguished historian John A. Garraty. Rothbard’s review, published in 1978, raised an issue that has come up in previous discussions of the Freakonomics phenomenon (1, 2, 3, 4): Can a little theory, without accompanying real-world knowledge, be a dangerous thing?

After chiding Garraty for writing about unemployment without knowing the basics of business-cycle theory, Rothbard adds:

My strictures against history which lacks any sound theoretical base are not meant to be an act of intellectual imperialism on behalf of economics and against history or other disciplines. Quite the contrary; the economist who ventures into the historical arena armed only with a few equations and mathematical razzle-dazzle has wreaked far more damage than the uninspired and slightly bumbling historian. For the economist, particularly the latter-day “cliometrician,” aims to flaunt his arrogant “scientific” pretensions of encompassing and explaining all of world history by means of a few mathematical symbols. The economist who knows no history understands far less than his opposite number in the historical profession; but his claims are far greater. Therefore, he is much wider off the mark.

Add to: Facebook | Digg | Del.icio.us | Stumbleupon | Reddit | Blinklist | Twitter | Technorati

Incentives Matter, Soviet Edition

| Dick Langlois |

As economists like Benito Arruñada and Eric Hilt have shown, fishing and whaling have always used an incentive system in which crew members are paid a share of the profits of the voyage. Recall that Ishmael in Moby Dick contracted for a 300th lay, a 300th “part of the clear nett proceeds of the voyage, whatever that might eventually amount to.” This provides relatively high-powered incentives, in that it is a reward based on results, though it works only when team members can monitor each other easily and when the market for workers is competitive. (This contrasts with the reward system in, say, professional sports, where one is rewarded on the basis of one’s own performance rather than on that of the team. But that may be changing.)

As economists like Benito Arruñada and Eric Hilt have shown, fishing and whaling have always used an incentive system in which crew members are paid a share of the profits of the voyage. Recall that Ishmael in Moby Dick contracted for a 300th lay, a 300th “part of the clear nett proceeds of the voyage, whatever that might eventually amount to.” This provides relatively high-powered incentives, in that it is a reward based on results, though it works only when team members can monitor each other easily and when the market for workers is competitive. (This contrasts with the reward system in, say, professional sports, where one is rewarded on the basis of one’s own performance rather than on that of the team. But that may be changing.)

I was surprised to discover that even Soviet factory ships used a similar system, as described in the Martin Cruz Smith novel Polar Star — a work of fiction but clearly well researched and probably accurate. “The Polar Star’s pay was shared on a coefficient from 2.55 shares for the captain to 0.8 share for a secondclass seaman. Then there was a polar coefficient of 1.5 for fishing in Arctic seas, a 10 percent bonus for one year’s service, a 10 percent bonus for meeting the ship’s quota, and a bonus as high as 40 percent for overfulfilling the plan. The quota was everything. It could be raised or lowered after the ship left dock, but was usually raised because the fleet manager drew his bonus from saving on seamen’s wages. Transit time to the fishing grounds was set at so many days, and the whole crew lost money when the captain ran into a storm, which was why Soviet ships sometimes went full steam ahead through fog and heavy seas.”

Presumably, however, the share was not of profit but of some fixed amount. The incentive came from the quota bonuses, which, as the novel details, were subject to political manipulation. Interesting nonetheless that the system used incentives of the broadly traditional kind, and that it explicitly rewarded workers differently for different skill level and status.

Add to: Facebook | Digg | Del.icio.us | Stumbleupon | Reddit | Blinklist | Twitter | Technorati

The History of Nikola Tesla

| Peter Klein |

Saturday was Nikola Tesla’s birthday. Here’s Jeremiah Warren’s video in Tesla’s honor:

Tesla was, of course, the great inventor whose technical achievements outshone those of his great rival, Thomas Edison, but who was unable to commercialize any of his discoveries. Tesla, unfortunately, put his faith in intellectual property-rights protection, while Edison emphasized management and marketing. As Danny Quah puts it, “Public relations and entrepreneurial savvy trump the raw intellectual idea.”

Add to: Facebook | Digg | Del.icio.us | Stumbleupon | Reddit | Blinklist | Twitter | Technorati

More on Managerial Coordination and the Vanishing Hand

| Dick Langlois |

Many many thanks to Mari Sako and Susan Helper for taking the time to comment on my post about their paper in ICC. To give the discussion more visibility, I am elevating my response to a new post.

My Vanishing Hand argument is an attempt to explain theoretically the demise of the large multi-unit Chandlerian enterprise, the essence of which was managerial coordination across vertically integrated stages of production. That is to say, my argument was about vertical disintegration. To assert that a more-disintegrated system still uses managerial coordination across firm boundaries is not to resurrect Chandler’s vision; it is to back away from Chandler’s vision. (I document Chandler’s vision, and its intellectual roots, with more care in the book than in the original “Vanishing Hand” paper.) My argument is fundamentally about vertical integration, and I have no problem with the idea that managerial coordination is often exercised across the boundaries of firms. I’ll return to this point in a second.

Sako and Helper argue that, if minimum efficient scale is falling, the size of firms should be falling. And Giovanni Dosi and his coauthors claim that firm size isn’t falling. Well, first of all, MES determines plant size not firm size. It sets a lower bound on firm size; it doesn’t guarantee a smaller firm size. But the real point here is: what does “size” mean? As I pointed out in my response to Dosi et al., their evidence is at best about firm size in the sense of price theory: number of widgets per unit time. My argument is about firm size in the sense of Coase: number of activities undertaken within the boundaries of the firm. Vertical disintegration is perfectly consistent with larger firm size in the sense of price theory; in fact, we might expect it. (more…)

Bailouts in Historical Perspective

| Peter Klein |

O&M has been consistently anti-bailout, whether recipients are banks, manufacturing firms, or homeowners. Besides encouraging moral hazard, bailouts also stymie the fundamental market process of moving productive assets from lower- to higher-valued uses. A market economy, after all, is a profit-and-loss system. Without losses, what’s the point?

A new edited volume, Bailouts: Public Money, Private Profit (Columbia University Press, 2010), explores bailouts in historical perspective, going back as far as the US financial crisis of 1792. Editor Robert Wright and his contributors try to steer a middle course, with Wright endorsing Hamilton’s Rule (formerly Bagehot’s Rule) of providing public loans to failing firms only if they have good collateral, and at “penalty” interest rates. Still, as Wright notes in his introduction, “There is no statistical evidence, however, that bailouts [of any kind] can speed economic recovery. In fact, bailouts can slow recovery by creating policy uncertainty, distorting market incentives, and in extreme cases fomenting sociopolitical unrest.”

Add to: Facebook | Digg | Del.icio.us | Stumbleupon | Reddit | Blinklist | Twitter | Technorati

In the Pink

| Dick Langlois |

A propos Peter’s recent post about behavioral economics, I discovered this interesting video illustrating Daniel Pink’s book Drive (thanks, Steve). I don’t think there is anything about it that is particularly inconsistent with what we know about the economics of organization, but others may disagree.

I once heard Pink speak, at the 2002 Business History Conference meeting, just after his book Free Agent Nation (about the rise of self-employment) appeared. He was one third of a panel on the New Economy, the rest of which consisted of two extremely far-left twits. It was amusing to hear Pink, a former speechwriter for Al Gore, gamely hold up a sensible position, though I remember thinking what greater fun it would have been if they had invited Virginia Postrel.

Add to: Facebook | Digg | Del.icio.us | Stumbleupon | Reddit | Blinklist | Twitter | Technorati

The “Knowledge Filter” and the New Economy

| Dick Langlois |

| Dick Langlois |

I recently ran across a paper by Bo Carlsson, Zoltan Acs, David Audretsch, and Pontus Braunerhjelm called “The Knowledge Filter, Entrepreneurship, and Economic Growth.” It’s actually a 2007 paper, part of a series these authors in various combination have been writing about the idea of a “knowledge filter.” The standard story about knowledge (in the new growth theory, but long before that as well) is what I think of as the R&D sausage-machine: one pours inputs like capital and labor into the meat grinder of R&D and out comes knowledge, which shifts the production function. In a series of papers, Carlsson et al. have argued that there is a “filter” somewhere within the meat grinder that determines how effectively the inputs get turned into useful knowledge. Although I’m sympathetic to criticism of the sausage machine story, you can imagine why I don’t think the knowledge-filter idea helps much: it’s just another black box that can be sized to fit whichever facts (stylized or real) one has at hand. Why not do away with the model altogether and instead think hard about the structure of knowledge and how it has interacted with institutions and organizational forms?

In fact, of course, that is what the authors actually do to some extent in this paper: one can read it without having to buy into the “filter” part. What caught my attention, in fact, is that this paper is ultimately an argument about the causes of the New Economy, and I am a collector of such arguments. The authors seem completely innocent of the large Post-Chandlerian literature on this topic, and they try to explain the transition from the large Chandlerian firm to more specialized entrepreneurial units strictly in terms of trends in R&D and knowledge creation.

[T]he industrial revolution was based in part on turning knowledge into economically useful knowledge and … university education and research in the United States became practically and vocationally oriented (in comparison with European universities), partly through the land-grant universities established in the mid- to late 19th century. In the early part of the 20th century, corporate research and development labs began to emerge as major vehicles of basic industrial research. Virtually all of the funded research prior to World War II was conducted in corporate or federal labs. In conjunction with a rapidly increasing share of the population with a college education, this made for high absorptive capacity on the part of industry and, as a result, a “thin” knowledge filter. In subsequent sections we discuss the emergence of the research university, the dramatic increase in research and development spending, and the shift of basic research toward the universities, especially during and following World War II. During the 1960s and 1970s, this led to a thickening of the knowledge filter in the form of an increasing need to “translate” basic (academic) research into economic activity. New firms have increasingly become the vehicle to translate research into growth; this can be seen in the greater role of small business and entrepreneurship from the 1970s onward.

Interesting. But I see two serious problems with this. First off, it misunderstands and vastly oversells the research labs of the mid-twentieth century. In most cases these were not drivers of innovation but absorbers of ideas invented outside the company by networks of smaller inventors — much like today. And when they did perform genuinely basic research, as in the case of Bell Labs, they were not at all tightly coupled to application. These labs were good at systemic development, that is, developing technologies that required a lot of disparate pieces to be created and put together. Color TV at RCA is an example. But they were not good at generating genuinely new useful knowledge or at more modular kinds of innovation — or, at least, weren’t as good as diffuse networks of inventors. In fact, as I mentioned in my previous post, the concentration of research (and patents) in the labs of RCA arguably slowed innovation in radio and consumer electronics generally. This leads to my second point: it’s not clear that one can explain everything just by looking at knowledge and R&D. There is actually a lot similarity between the regime of government funding of research through Land Grant institutions and the post-War grant system of Vannevar Bush: it was always channeled through the universities. Changes in government funding thus can’t really explain why there were large R&D labs at one time and small entrepreneurial firms at another. For that one has to think about issues of organization that go beyond the R&D function.

Intellectual Steam

| Dick Langlois |

There’s nothing like a rousing academic argument, especially when it deals with an intriguing historical case. “The Fable of the Keys” by Liebowitz and Margolis is the paradigm here. I recently stumbled upon another example, the (apparently ongoing) dispute that pits George Selgin and John Turner against Michele Boldrin and David Levine on the question of to what extent James Watt’s steam-engine patents retarded innovation in steam technology and slowed the British industrial revolution.

There’s nothing like a rousing academic argument, especially when it deals with an intriguing historical case. “The Fable of the Keys” by Liebowitz and Margolis is the paradigm here. I recently stumbled upon another example, the (apparently ongoing) dispute that pits George Selgin and John Turner against Michele Boldrin and David Levine on the question of to what extent James Watt’s steam-engine patents retarded innovation in steam technology and slowed the British industrial revolution.

The Newcomen steam engine was a low-pressure device that, by using steam to create a vacuum, actually used air pressure to drive the engine. Watt invented and patented an improvement to the vacuum engine that involved a separate condenser to cool the steam, thus increasing efficiency. On the strength of his patent, Watt was bankrolled by the industrialist Matthew Boulton, and together they licensed the technology to others and did their best to block competing technology. Boldrin and Levine claim that the Watt patent constituted a wide-scope blocking patent, of the kind described by Merges and Nelson, which slowed development of rival technologies, including the high-pressure steam engine that was to be crucial in textiles and elsewhere. As a result, the Boulton-Watt patents and legal stratagems “delayed the industrial revolution by a couple of decades.” Selgin and Turner take issue with both facts and conclusions, arguing that patent law at the time, which derived from the 1625 Statute of Monopolies, actually forbade the patenting of a general idea and insisted that an innovation be instantiated in specific technology, in this case in the form of the condenser. In other words, they argue that patent scope was kept sensibly low in eighteenth-century Britain, something of which Merges and Nelson would approve. Thus Boulton and Watt could not, and in fact did not, slow the development of high-pressure steam through intellectual property, though they may have had an effect on the culture of contemporary inventors, who doubted the economies and feared the dangers of high-pressure steam at a time when complementary metallurgical technology was not yet up to the task. (Note to Selgin and Turner: here is a better reference on the dangers of high-pressure boilers in American steamboats.) (more…)

The Invention of Enterprise: Reviews

| Peter Klein |

If you haven’t yet had a chance to read Landes, Mokyr, and Baumol’s 600-page baby, The Invention of Enterprise: Entrepreneurship from Ancient Mesopotamia to Modern Times, here are reviews by Mansel Blackford and Reuven Brenner. Blackford is impressed; Brenner, not so much. Brenner is worth quoting at length:

[L]arge chunks of the book are more about the topic of inhibitions to enterprise and both the variety of ideas people came up with to rationalize them and the institutions rulers and governments put in place to enforce these ideologies. . . .

Unfortunately most of the chapters dealing with the topic of inhibitions miss the forest from the trees, as not one addresses what is to me the basic issue when examining “the invention of enterprise.” There is nothing more threatening to an established order — any order — than opening up, deepening, democratizing capital markets — accountably, allowing people to leverage their inventive, enterprising spirit. True, this would also disperse power — political power in particular. The deeper capital markets would also threaten established industries and commerce. Entrepreneurs, brilliant and ambitious as they might be, are not a threat. They can be sent to Siberia, forced into complacency by the Maos of this world, and the opportunistic ones will channel their ambition through the established powers.

But entrepreneurs with access to different, independent sources of risk capital — now that’s threatening, be they Brin and Page, Jobs or Milken at the time (quickly taking away much of the banks’ bread and butter of providing loans). Understanding this, even if not wanting to articulate it, provides enough incentives for those in power to subsidize, spread, and promote ideas and institutions inhibiting the deepening of capital markets under a wide variety of jargons, and thus inhibiting the invention and reinvention of enterprises. With time, people get accustomed to these institutions, their origins lost in the mist of time, inhibiting entrepreneurship and business for centuries. Today this may be happening a bit before our eyes. Suddenly, everything becomes a “bubble” — Internet, oil, houses, gold, bonds. Guess what: if everything is — why have capital markets to start with? If pricing no longer offers guidance to allocate capital; if stock and bond markets are not there to help correct mistakes faster — why should they continue to exist? And if they do not exist, who else remains but politicians, bureaucrats and the academics surrounding them — none of whom ever worked in a business even one day in their lives — who would then tax and borrow and subsequently allocate capital and “invent enterprises” based on — well — whatever.

Add to: Facebook | Digg | Del.icio.us | Stumbleupon | Reddit | Blinklist | Twitter | Technorati

Greenstein on Innovation

| Peter Klein |

One of my regular lectures at the Mises University deals with the economics of networks and information technology, with a particular focus on the history of the internet. A few years ago I wrote up my notes for a Mises.org daily article, which appeared as “Government Did Invent the Internet, But the Market Made It Glorious.” Shane Greensteinn’s new NBER paper could used the same title, though he chose something meatier: “Nurturing the Accumulation of Innovations: Lessons from the Internet.” Okay, the paper is a bit meatier too. Check it out:

The innovations that became the foundation for the Internet originate from two eras that illustrate two distinct models for accumulating innovations over the long haul. The pre-commercial era illustrates the operation of several useful non-market institutional arrangements. It also illustrates a potential drawback to government sponsorship — in this instance, truncation of exploratory activity. The commercial era illustrates a rather different set of lessons. It highlights the extraordinary power of market-oriented and widely distributed investment and adoption, which illustrates the power of market experimentation to foster innovative activity. It also illustrates a few of the conditions necessary to unleash value creation from such accumulated lessons, such as standards development and competition, and nurturing legal and regulatory policies.

Add to: Facebook | Digg | Del.icio.us | Stumbleupon | Reddit | Blinklist | Twitter | Technorati

Recent Comments