Posts filed under ‘Classical Liberalism’

Preaching from the Choir

| Dick Langlois |

It’s hard to top Bruce Kogut on the Daily Show. But by sheer coincidence I happened upon a video that offers a quite different perspective on corporate social responsibility.

Attack of the Public Finance Utility Monsters

| Dick Langlois |

I just saw this amusing abstract from Greg Mankiw. I think it will be far too subtle for most people.

The Optimal Taxation of Height: A Case Study of Utilitarian Income Redistribution

Should the income tax include a credit for short taxpayers and a surcharge for tall ones? The standard Utilitarian framework for tax analysis answers this question in the affirmative. Moreover, a plausible parameterization using data on height and wages implies a substantial height tax: a tall person earning $50,000 should pay $4,500 more in tax than a short person. One interpretation is that personal attributes correlated with wages should be considered more widely for determining taxes. Alternatively, if policies such as a height tax are rejected, then the standard Utilitarian framework must fail to capture intuitive notions of distributive justice.

Extra credit: how would such a tax affect NBA salaries — like that of UConn’s seven-foot-three Hasheem Thabeet, who was taken number two in the recent draft?

Why “Doing Business” Leads to Bad Policy

| Benito Arruñada |

In a post at the PSD blog, David Kaplan sees little difference between the “Doing Business” position and my own. He writes:

Part of Professor Arruñada’s argument is that the Doing Business indicators do not capture all the relevant components of the business environment. The writers of the Doing Business 2009 report agree. . . .

I believe that the debate is not mainly about what Doing Business measures. Really, the debate is about how these measures are used in shaping public policy. Critics of Doing Business are concerned that countries will ignore the above warnings and only reform in areas that are measured in Doing Business.

I doubt that one can separate what DB measures and how it does it from how DB measures are used in the field. My main complaint, however, is different, namely that the DB method has often led to bad policy. (more…)

Does Capitalism Suffer Cycles of Statism?

| Benito Arruñada |

Does the current expansion of the State reverse a previous reduction, to be reduced once again in the future? Or, alternatively, is there a sort of ratchet effect, with a trend towards greater statism disguised by cycles along such increasing trend?

I am inclined to think that cycling has not taken place around a stationary average but around an increasing tendency (see the figures). But perhaps a better way of facing these questions would be to disaggregate in different dimensions. For instance, in several papers with Veneta Andonova we argue that freedom

I am inclined to think that cycling has not taken place around a stationary average but around an increasing tendency (see the figures). But perhaps a better way of facing these questions would be to disaggregate in different dimensions. For instance, in several papers with Veneta Andonova we argue that freedom  of contract has been in decline for more than a century in Western Law, both in civil- and common-law countries. Something similar could probably be said about trade, but in the opposite direction. However, in both freedom of contract and trade, it might be the case that exchange opportunities have expanded mainly as a result of technological change (e.g., cheaper transportation and communications), whatever the legal constraints. In terms of research, how could these trends be measured?

of contract has been in decline for more than a century in Western Law, both in civil- and common-law countries. Something similar could probably be said about trade, but in the opposite direction. However, in both freedom of contract and trade, it might be the case that exchange opportunities have expanded mainly as a result of technological change (e.g., cheaper transportation and communications), whatever the legal constraints. In terms of research, how could these trends be measured?

These thoughts were triggered by a timely and extremely suggestive paper by Witold J. Henisz presented at the Workshop on “Manufacturing Markets” organized last week in Villa Finaly, Florence, by Eric Brousseau and Jean-Michel Glachant. My next few blogs will address other aspects of Henisz’s views on the broader challenges facing capitalism.

Mises and Hayek in Progress in Human Geography

| Nicolai Foss |

It is surprising, even bizarre, to see Mises and Hayek, as well as other luminaries of 20th-century classical liberalism, being extensively cited, quoted, and discussed in one of the leading geography journals, Progress in Human Geography (here is the wiki on the field of “human geography”), specifically in the form of the printed version of an invited lecture by Jamie Peck. (more…)

You Go, Gordon Gekko!

| Peter Klein |

Several folks in my part of the blogosphere have noted John Hasnas’s terrific op-ed in yesterday’s WSJ, “The ‘Unseen’ Deserve Empathy, Too.” Hasnas invokes the great Bastiat to counter President Obama’s call for judges who have compassion, empathy, and understanding of “people’s hopes and struggles.” As Hasnas points out, judges should consider the effects of legal rulings not only on the parties before the bar, but also on the “unseen” whose lives will be affected:

One can have compassion for workers who lose their jobs when a plant closes. They can be seen. One cannot have compassion for unknown persons in other industries who do not receive job offers when a compassionate government subsidizes an unprofitable plant. The potential employees not hired are unseen. . . .

The law consists of abstract rules because we know that, as human beings, judges are unable to foresee all of the long-term consequences of their decisions and may be unduly influenced by the immediate, visible effects of these decisions. The rules of law are designed in part to strike the proper balance between the interests of those who are seen and those who are not seen. The purpose of the rules is to enable judges to resist the emotionally engaging temptation to relieve the plight of those they can see and empathize with, even when doing so would be unfair to those they cannot see.

This was on my mind when, channel surfing last night, I came across Oliver Stone’s 1987 classic “Wall Street,” which I haven’t seen in its entirety in years. To my surprise (perhaps not yours), I found myself rooting for Michael Douglas’s Gordon Gekko, the corporate raider who serves as the movie’s arch-villain. The main sub-plot revolves around Gekko’s attempted buyout of Blue Star Airlines. Bud thinks the buyout can save the struggling airline, where his father still works, and helps convince the pilots’ and flight attendants’ unions to Gekko’s move. Later, Bud discovers Gekko is really planning to break up the company and sell off the pieces and Bud feels betrayed, leading to a climactic confrontation. (The film feels remarkably fresh, despite the glowing green CRT screens and brick-sized cellular phones, and Douglas’s performance is dazzling.) (more…)

This was on my mind when, channel surfing last night, I came across Oliver Stone’s 1987 classic “Wall Street,” which I haven’t seen in its entirety in years. To my surprise (perhaps not yours), I found myself rooting for Michael Douglas’s Gordon Gekko, the corporate raider who serves as the movie’s arch-villain. The main sub-plot revolves around Gekko’s attempted buyout of Blue Star Airlines. Bud thinks the buyout can save the struggling airline, where his father still works, and helps convince the pilots’ and flight attendants’ unions to Gekko’s move. Later, Bud discovers Gekko is really planning to break up the company and sell off the pieces and Bud feels betrayed, leading to a climactic confrontation. (The film feels remarkably fresh, despite the glowing green CRT screens and brick-sized cellular phones, and Douglas’s performance is dazzling.) (more…)

Deregulation and the Financial Crisis

| Peter Klein |

Niall Ferguson joins Charles Calomiris, Jerry O’Driscoll, Arnold Kling, and many others in questioning the supposed link between “deregulation” and the financial crisis. As Ferguson emphasizes, the timing is all wrong; there is no time-series correlation between specific patterns of regulation and deregulation and particular financial or economic outcomes. The relaxation of Glass-Steagall restrictions on universal banking is an oft-cited example, but, as these writers point out, no one has offered any specific mechanism by which universal banking contributed to the problem (indeed, the opposite is likely to be true). The “laissez-faire caused the crisis” meme may be pithy, but is there any systematic theoretical or empirical evidence for it?

Ferguson has the best line (suggested by Luke): “It is indeed impressive how rapidly the economists who failed to predict this crisis . . . have been able to produce such a satisfying story about its origins.”

More on Adam Smith’s Metaphor

| Peter Klein |

If you enjoyed our earlier discussion of social science’s most famous metaphor — come on, guys, is “iron cage” even in the same ballpark? — see the current issue of EconJournalWatch, which features essays on the invisible hand by Gavin Kennedy and Dan Klein.

If you enjoyed our earlier discussion of social science’s most famous metaphor — come on, guys, is “iron cage” even in the same ballpark? — see the current issue of EconJournalWatch, which features essays on the invisible hand by Gavin Kennedy and Dan Klein.

Cheer Up With the Depression Bundle

| Peter Klein |

Sorry, couldn’t resist the headline. But check it out: Murray Rothbard’s America’s Great Depression, Bob Murphy’s Politically Incorrect Guide to the Great Depression and the New Deal, Dave Beito’s Taxpayers in Revolt, and John T. Flynn’s Roosevelt Myth, all for $49! That’s quite an uplifting deal.

Sorry, couldn’t resist the headline. But check it out: Murray Rothbard’s America’s Great Depression, Bob Murphy’s Politically Incorrect Guide to the Great Depression and the New Deal, Dave Beito’s Taxpayers in Revolt, and John T. Flynn’s Roosevelt Myth, all for $49! That’s quite an uplifting deal.

More great news: Contra Keynes and Cambridge, vol. 9 of Hayek’s Collected Works, is now out in paperback from Liberty Fund, and just $14.50.

Macroeconomic Policy Quote of the Day

| Peter Klein |

Mike Rozeff makes the Hayekian point that is probably obvious to the O&M community, but virtually absent from public debate:

Bernanke is just a man. He is fallible. We learned this week that he pressured Bank of America into absorbing Merrill Lynch. In doing this, he pressured the leader of Bank of America into withholding critical information from his shareholders about Merrill Lynch losses. Technically, he can be charged with conspiracy to defraud. The loans he had the FED make to AIG look far from wise. A number of his other actions are highly questionable in making various kinds of loans to questionable borrowers.

I am saying that Bernanke doesn’t actually know what he’s doing. But I am using him only as an example. He’s not special. The more important point is that no one knows how to do fiscal and monetary policy, and they never have and never will. No one. For that reason alone, which is a narrowly practical one, no one should have those powers.

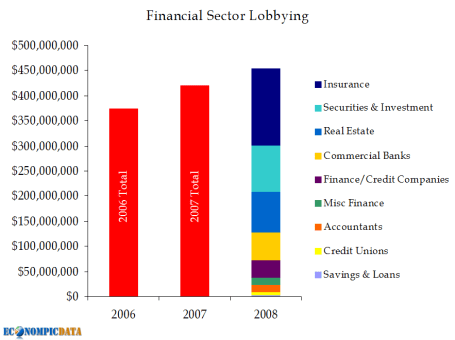

One Part of the Financial Sector Is Still Growing

| Peter Klein |

Courtesy of EconomPicData:

It takes money to make money, you know.

Keynesian Economics in a Nutshell

| Peter Klein |

An earlier post on Keynesian economics in four paragraphs has proven extremely popular. Here’s Keynesian economics in just one-and-a-half paragraphs, courtesy of Mario Rizzo:

Clearly, DeLong is a rigid aggregate demand theorist. He talks about output and employment as if it were some homogeneous thing. In his mind, macroeconomics is just about spending to increase the production of stuff. Yes, there is lip service to the idea that the stuff should have economic value. But that is easy when you assume that the only alternative is value-less idleness. . . .

The sectoral problems generated, not only by exogenous shocks but by the low interest rate policy of the Fed, are of critical importance. The aggregate demanders are blind to this.

Here at O&M we take the opposite perspective, namely that heterogeneity matters. Actually, as Mario has pointed out in a series of posts (1, 2, 3), Keynes himself was much better than his latter-day followers. Keynes may have been wrong — deeply, deeply wrong, in my view — but he was no fool. As for today’s Keynesians. . . .

Update (14 April): See also Mario’s fine essay in the April Freeman, “A Microeconomist’s Protest.”

Adam Smith’s Famous Metaphor

| Peter Klein |

The indefatigable Gavin Kennedy explains, for the umpteenth time, that Adam Smith was ambivalent about market capitalism and that the famous metaphor of the “invisible hand” was not meant as a generalized defense of the market. As Gavin points out, Smith’s detailed analysis of the market economy appears in Books I and II of the Wealth of Nations, while the invisible hand metaphor appears only once, in Book IV, where Smith defends British merchants who, despite mercantilist export subsidies, preferred to keep their capital invested at home, to the benefit of the British economy. Notes Gavin:

So inconsequential was [Smith’s] use of The Metaphor that neither he, nor anybody else until the late 19th century, commented upon it. . . .

Moreover, it was only in Chicago in the 1930s that The Metaphor was generalised into Smith’s so-called “law” of markets. Paul Samuelson (1948, 1st edition), in his famous textbook, Economics (16 editions), publicised this invention with the inevitable affect on modern economics, as tens of thousands of his readers took it on trust as true.

To be sure, the relevant passage in Smith also includes the famous lines, “By pursuing his own interest he frequently promotes that of the society more effectually than when he really intends to promote it. I have never known much good done by those who affected to trade for the public good,” and the remark that “What is prudence in the conduct of every private family can scarce be folly in that of a great kingdom.” But Smith’s statements need to be understood in context; he is discussing the specific problem of trade monopoly, arguing against trade and industrial policies that subsidize particular markets or industries.

New Friedman Book

| Nicolai Foss |

K. Puttaswamaiah has edited Milton Friedman, Nobel Monetary Economist: A Review of his Theories and Policies (Isle Publishing Co., 2009). I only know the names of a few of the contributors, but I do recognize a certain Samuelson, who recently “remembered” Friedrich Hayek in a scandalously superficial and misleading note published in the pages of the Journal of Economic Organization and Behavior. Ones hopes that Friedman isn’t up for a similar treatment, but perhaps he is: One of the chapters in the volume is titled, “Milton Friedman: A Late and Overestimated Master of Sophistry.”

Why They Heart Keynes

| Peter Klein |

Luigi Zingales offers Straight Talk on Keynes (via Casey Mulligan):

Keynesianism has conquered the hearts and minds of politicians and ordinary people alike because it provides a theoretical justification for irresponsible behavior. Medical science has established that one or two glasses of wine per day are good for your long-term health, but no doctor would recommend a recovering alcoholic to follow this prescription. Unfortunately, Keynesian economists do exactly this. They tell politicians, who are addicted to spending our money, that government expenditures are good. And they tell consumers, who are affected by severe spending problems, that consuming is good, while saving is bad. In medicine, such behaviour would get you expelled from the medical profession; in economics, it gives you a job in Washington.

Three comments: First, the “hangover” metaphor, while not exactly accurate, is an effective way to communicate the basics of the Mises-Hayek malinvestment theory of the business cycle. Use it! Second, Zingales’s description applies equally well to the 1930s and 1940s, when the Keynesian consensus emerged. It’s important to remember that massive deficit spending to “cure” the Depression began with Hoover and Roosevelt in the early 1930s, long before the General Theory appeared. Keynes’s book did not propose a new direction for economic policy; it provided an allegedly scientific rationale for policies already in place, policies government officials were eager to defend and protect. (The use of expansionary fiscal and monetary policy to increase output had long been derided by serious economists as nonsense, as the domain of “monetary cranks” and other snake-oil salesmen).

Third, the Keynesian delusion afflicts not only policymakers, but professional economists as well. I’ve long suspected that the appeal of Keynes to people like Krugman and DeLong is ultimately based on aesthetic, not scientific, grounds. Deep in their hearts, they just don’t like private property, markets, and individual choice. They don’t think ordinary people are capable of making wise decisions and think they, the elites, should be in charge. They resent the fact that most people don’t want their lives controlled by liberal intellectuals. Technical arguments about the effectiveness of monetary and fiscal policy, the relationship between aggregate demand and output, the experience of the 1930s, and the like are really beside the point. For Keynesian economists, the belief that markets are naturally unstable in the absence of government planning is a matter of faith.

Ah, Democracy!

| Peter Klein |

I learned this week from Doug French that Dissident Books has published a new edition of H. L. Mencken’s classic and extremely politically incorrect Notes on Democracy. Who but Mencken could write that the common man “is not actually happy when free; he is uncomfortable, a bit alarmed, and intolerably lonely. He longs for the warm, reassuring smell of the herd, and is willing to take the herdsman with it.” As for democratically elected politicians, Mencken reminds us how quickly all those sappy paeans to the people’s will evaporate when a “crisis,” real or imagined, is on the horizon. “All the great tribunes of democracy, on such occasions, convert themselves, by a process as simple as taking a deep breath, into despots of an almost fabulous ferocity. Lincoln, Roosevelt and Wilson come instantly to mind.”

This was on my mind when I read (via Kathryn Muratore) about a new study appearing in Science finding that children looking at pictures of political candidates correctly pick the eventual winner 64% of the time. Apparently we are hard-wired to prefer pretty faces, even when supposedly choosing based on policy views, ideology, “the issues,” etc . So much for the rational voter.

What Does a Trillion Dollars Look Like?

| Peter Klein |

As they say, trillion is the new billion, where bailouts and government debt are concerned (1, 2). Just how much is a trillion dollars anyway? Here it is in pictures (via MGK).

Viral Marketing

| Peter Klein |

My friend Tom Woods has written a new book, Meltdown, that explains the economic crisis from an “Austrian” perspective. Tom is a historian by training but has an excellent grasp of economic theory and policy (disclaimer: I consulted on the book). The book is aimed at the intelligent lay reader and was produced very quickly (Tom writes faster than I read) to take advantage of today’s unique educational moment. The book went on sale today.

Tom is promoting the book via the usual means (scholarly and popular websites and blogs, email lists, some TV and radio appearances) and some of his admirers have launched a viral marketing campaign, based at GetTomonTV.com. Can viral marketing work to promote a quasi-academic book? Will policy wonks, economic journalists, and concerned citizens blog, text, and twitter like Blair Witch groupies or Christian Bale fans? How does one promote books (and, for that matter, journal articles) in the Web 2.0 world? Most important, how do I use this knowledge to promote myself?

Hayek on the Austrians

Those of you longing for a copy of my favorite volume in Hayek’s Collected Works, but unwilling to pay the hefty University of Chicago Press or Routledge price, can now get a handsome paperback edition for only $12, thanks to Liberty Press. The brilliant introduction and copious editor’s footnotes alone are worth the price!

Stimulus Haiku

| Peter Klein |

| Peter Klein |

From the great Bob Higgs:

Billions come bursting

From huge hydrants of money

I am stimulatedCredit freeze thaws now

Fed heats pipes until they steam

Winter is lovelyConsumers feel fine

Ready to mortgage their souls

John Maynard Keynes smilesSaving’s so passe

Capital stock may be assumed

Let K be capitalGiant debt you bet

Chinese will serve fine dinner

Children cannot voteLike rose in springtime

Welfare state blossoms anew

Laughter heard in hell

Feel free to try your hand in the comments section below. See also Bob’s reflections on the Inauguration.

Update: See also Morgan Reynolds’s bailout version of “I Fought the Law.”

Recent Comments