Posts filed under ‘Classical Liberalism’

Public Choice and Austrian Economics

| Peter Klein |

The Austrian school and the Public Choice or Virginia school of economics are often tightly linked, both among the lay public and within academic circles. The connection isn’t obvious, however. While members of both schools tend to have classical-liberal views on political economy, the Virginia school emerged from the Chicago public finance tradition (Buchanan, after all, was a student and disciple of Knight) and is thoroughly “neoclassical” in orientation. Public choice economists tend to look to Chicago, not Vienna, for inspiration.

Anamaria Berea, Art Carden, and Jeremy Horpedahl take a different tack, drawing out common threads in Buchanan’s and Hayek’s subjectivist approach to cost.

Cost and Choice and The Sensory Order represent tangents from the basic research programs of their respective authors, James M. Buchanan and F.A. Hayek. These seeming diversions into methodology by two political-economic philosophers help to shed light on their underlying assumptions about cost and rationality. We argue that Buchanan and Hayek, and consequently Public Choice and Austrian Economics, have very similar underlying assumptions about the nature of cost. This can help to explain other similarities between the two schools, especially regarding the role of the state. These contributions are synthesized and applied to debates over the “new paternalism” and military conscription.

Tom DiLorenzo’s 1990 paper “The Subjectivist Roots of James Buchanan’s Economics” is also worth consulting on this connection. The question, though, is whether Cost and Choice (and the later Buchanan and Thirlby-edited volume, LSE Essays on Cost) is a consistent with the rest of the public choice tradition (including Buchanan’s own work).

NB: In graduate school I was exposed to the “positive political theory” (PPT) literature associated with Riker, Shepsle, Weingast, etc. and was surprised that the Virginia school was never mentiond in the discussion. A prominent PPT scholar told me once that PPT is “scientific,” while public choice is merely “ideological” and “low-tech.” Fair or not, I think this view is widespread among younger scholars. Has anyone written a good comparison of PPT and the public-choice approach?

Rothbard on Big Business

| Peter Klein |

We at O&M are sometimes described as “pro-business.” But this is not correct. We strongly support the economic function of commerce, and we think private ownership of capital, the profit-seeking activities of entrepreneurs and managers, and unfettered markets for consumer goods, factors of production, and financial assets are essential to a strong economy. But that doesn’t mean we admire the behavior and character of every capitalist, entrepreneur, and manager. Indeed, plenty are scoundrels. Empirically, the businesspeople who rise to the top in today’s mixed economy, with its peculiar blend of free markets and state controls, are likely to be those who excel in political entrepreneurship, in “working the system” to their advantage.

Murray Rothbard summarizes this view in a private letter written in 1966:

For some time I have come to the conclusion that the grave deficiency in the current output and thinking of our libertarians and “classical liberals” is an enormous blind spot when it comes to big business. There is a tendency to worship Big Business per se. . . and a corollary tendency to fail to realize that while big business would indeed merit praise if they won that bigness on the purely free market, that in the contemporary world of total neo-mercantilism and what is essentially a neo-fascist “corporate state,” bigness is a priori highly suspect, because Big Business most likely got that way through an intricate and decisive network of subsidies, privileges, and direct and indirect grants of monopoly protection.

Rothbard refers his correspondent to Gabriel Kolko, William Appleman Williams, James Weinstein, C. Wright Mills, and other New Left critics of the corporate state for details. For more on Rothbard’s own views see “Left and Right: The Prospects for Liberty” (1965) and “Confessions of a Right-Wing Liberal” (1968), as well as related essays by Joseph Stromberg and Roy Childs.

Call For an Annual Adam Smith Festival

| Peter Klein |

In 1990 I was privileged to attend a conference on “Adam Smith and his Legacy” commemorating the 200th anniversary of Smith’s death. The speakers included eight of the twenty Economics Nobel Laureates then living along with Smith scholars such as Andrew Skinner, general editor of the 1976 Glasgow edition of Smith’s Works and Correspondence. The papers were published in this book; you can read my conference report here. Listening to and visiting with the Laureates was fun, though I didn’t learn much about Adam Smith at the conference (most economists — Nobel Laureates included — know and care little about the history of economic thought). There was also an event at Smith’s grave in Canongate Kirk. (Somewhere I have a picture of myself at the site of Smith’s birthplace in Kirkcaldy; it’s basically me standing next to this).

In 1990 I was privileged to attend a conference on “Adam Smith and his Legacy” commemorating the 200th anniversary of Smith’s death. The speakers included eight of the twenty Economics Nobel Laureates then living along with Smith scholars such as Andrew Skinner, general editor of the 1976 Glasgow edition of Smith’s Works and Correspondence. The papers were published in this book; you can read my conference report here. Listening to and visiting with the Laureates was fun, though I didn’t learn much about Adam Smith at the conference (most economists — Nobel Laureates included — know and care little about the history of economic thought). There was also an event at Smith’s grave in Canongate Kirk. (Somewhere I have a picture of myself at the site of Smith’s birthplace in Kirkcaldy; it’s basically me standing next to this).

From Gavin Kennedy I learn that Eamonn Butler has called for an annual Adam Smith Festival, to be held each summer in Edinburgh. The city already holds an internationally recognized and highly successful arts festival so it knows how to do this sort of thing. Butler proposes several activities that could be part of a Smith festival then adds, wryly:

[O]ther people will have their own ideas. After all, it would not do for an Adam Smith Festival to be too rigidly planned. How much more appropriate it would be if different people’s initiatives came together — as if led, indeed, by an invisible hand.

Moral Hazard, For Real

| Peter Klein |

I suppose I posted a whimsical item about moral hazard because I was too angry to write anything about the Financial Irresponsiblity Bailout and Reward Act of 2008, the moral-hazard story of the decade. Buy more house than you can afford? Sign a mortgage contract you can’t understand? Invest in risky mortgage-backed securities that lose money? Run your financial institution into the ground? Don’t worry, the hapless US taxpayer will pick up the tab!

I have nothing but contempt in my heart for all who asked for, drafted, and voted for this odious piece of legislation. If there were any doubt that the US is, in many ways, a socialist economy, this massive socialization of financial-market risk should put such doubts to rest. Capitalism, requiescat in pace.

New Edition of Hayek’s Early Works

| Peter Klein |

The Mises Institute has just released a new edition of Hayek’s early works on economic theory, Prices and Production and Other Works: F. A. Hayek on Money, the Business Cycle, and the Gold Standard, edited and introduced by Joe Salerno. It collects the monographs Prices and Production, Monetary Theory and the Trade Cycle, and Monetary Nationalism and International Stability, along with the important essays “The Paradox of Saving,” “Reflections on the Pure Theory of Money of Mr. J.M. Keynes,” “The Mythology of Capital,” and “Investment That Raises the Demand for Capital.” These works, written between 1929 and 1937, established Hayek’s reputation as one of the great technical economists of his day, and the leading opponent of Keynes in monetary and business-cycle theory. Ironically, Hayek is mostly known today for his popular writings, particularly The Road to Serfdom, and for his later work on knowledge, evolution, and social theory. It is often forgotten that he was first and foremost an economic theorist.

The Mises Institute has just released a new edition of Hayek’s early works on economic theory, Prices and Production and Other Works: F. A. Hayek on Money, the Business Cycle, and the Gold Standard, edited and introduced by Joe Salerno. It collects the monographs Prices and Production, Monetary Theory and the Trade Cycle, and Monetary Nationalism and International Stability, along with the important essays “The Paradox of Saving,” “Reflections on the Pure Theory of Money of Mr. J.M. Keynes,” “The Mythology of Capital,” and “Investment That Raises the Demand for Capital.” These works, written between 1929 and 1937, established Hayek’s reputation as one of the great technical economists of his day, and the leading opponent of Keynes in monetary and business-cycle theory. Ironically, Hayek is mostly known today for his popular writings, particularly The Road to Serfdom, and for his later work on knowledge, evolution, and social theory. It is often forgotten that he was first and foremost an economic theorist.

Here is a detailed Hayek bibliography (through 1982) compiled by Leonard Liggio. Here’s a biographical essay written by yours truly. Here is the home page of the Collected Works of F. A. Hayek (and a pointer to my favorite volume). And it’s never too early to begin preparations for this important holiday.

Update: By coincidence, Collected Works editor Bruce Caldwell was interviewed in today’s Carolina Journal about his new edition of The Road to Serfdom.

V for von Mises

| Dick Langlois |

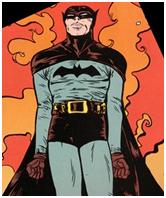

My Father’s Day present this year was something unusual: issue number 11 (Winter 1998) of something called The Batman Chronicles. (My sons are both into comics and graphic novels, though it was apparently my wife who stumbled onto this on the web.) The issue is a slim comic book featuring “The Berlin Batman,” wherein the story of Batman is reimagined as having taken place in pre-war Nazi Germany. The hero is Baruch Wane, wealthy Jewish socialite and decadent cubist painter, who becomes Batman by night after his parents are killed not by a robber but by anti-Semitic violence. His mission, of course, is to fight the tyranny of Nazism, which in this issue involves — and here’s the punch line — trying (in the end without success) to save the papers of Ludwig von Mises, which have been confiscated by the Nazis. The episode goes into great detail about why the work of von Mises was a threat to the Nazis and to authoritarians of all stripe.

My Father’s Day present this year was something unusual: issue number 11 (Winter 1998) of something called The Batman Chronicles. (My sons are both into comics and graphic novels, though it was apparently my wife who stumbled onto this on the web.) The issue is a slim comic book featuring “The Berlin Batman,” wherein the story of Batman is reimagined as having taken place in pre-war Nazi Germany. The hero is Baruch Wane, wealthy Jewish socialite and decadent cubist painter, who becomes Batman by night after his parents are killed not by a robber but by anti-Semitic violence. His mission, of course, is to fight the tyranny of Nazism, which in this issue involves — and here’s the punch line — trying (in the end without success) to save the papers of Ludwig von Mises, which have been confiscated by the Nazis. The episode goes into great detail about why the work of von Mises was a threat to the Nazis and to authoritarians of all stripe.

This comic may be old news to many readers, but I found it amusing. The author, Paul Pope, is apparently well respected in comics/graphic novel circles for, among other things, a more elaborate reimagining of Batman in a totalitarian future.

Sudha R. Shenoy (1943-2008)

| Peter Klein |

I’m saddened to report the death yesterday of Sudha Shenoy, the distinguished Australian economic historian and important contributor to the “Austrian revival” of the 1970s. Her father, the eminent Indian economist B. R. Shenoy, was a student at the London School of Economics in the 1930s when Hayek gave his famous “Prices and Production” lectures and both father and daughter were deeply influenced by Hayek. Sudha too studied at the LSE and eventually took a position at the University of Newcastle, where she taught until her retirement in 2004. Sudha was writing a book on Hayek and would have given a week-long lecture series on Hayek at the Mises Institute this fall. Here is a 2003 interview, here are some audios and videos, and here are some materials collected by Google Scholar. Some obituaries and personal remembrances are here, here, and here.

Suhda was a regular reader and occasional commentator here at O&M. You can get a sense of her erudition from this blog post, one of our most popular, which was basically a cut-and-paste job from one of her emails.

Suhda was a quiet, kind, and gentle person. This may be hard for our younger American readers to comprehend but she didn’t know how to drive. I once had the pleasure of chauffeuring her around Auburn, Alabama at an Austrian Scholars Conference. Spending time with her was a real treat.

Mike and Me on Externalities

| Peter Klein |

Mike Moffatt responds to my post on externalities. I questioned the Pigouvian approach of using taxes as efficient remedies for negative externalities. I said if, say, carbon taxes are a good idea, then Pigouvian taxes on a range of activities that generate negative externalities should be even better. And what about Pigouvian subsidies? I rarely see members of the Pigou club explain what activities they would subsidize, at what rates, and with what resources.

Mike Moffatt responds to my post on externalities. I questioned the Pigouvian approach of using taxes as efficient remedies for negative externalities. I said if, say, carbon taxes are a good idea, then Pigouvian taxes on a range of activities that generate negative externalities should be even better. And what about Pigouvian subsidies? I rarely see members of the Pigou club explain what activities they would subsidize, at what rates, and with what resources.

Mike’s response, based on more detailed comments here, is interesting, but to my mind misses the main point. Pigouvian taxes aren’t perfect, Mike says, but neither are income taxes or excise taxes or any other taxes. Fine, I say, but the relevant comparison isn’t between Pigouvian taxes and other taxes, but between Pigouvian taxes and alternative institutions for dealing with externalities such as cap-and-trade, common-law tort remedies, etc. (more…)

The Klein Doctrine

| Peter Klein |

That’s the title of Johan Norberg’s new report ripping Cousin Naomi’s The Shock Doctrine: The Rise of Disaster Capitalism. Great subtitle: “The Rise of Disaster Polemics.” Here’s Norberg: “Klein’s analysis is hopelessly flawed at virtually every level. . . . Klein’s historical examples also fall apart under scrutiny. . . . Klein’s broader empirical claims fare no better.” Indeed, an embarrassment for Kleins everywhere. (HT: Steve Horwitz)

Update from Per Bylund: “This guy will publish a whole book on Naomi Klein later this year, published by Timbro (in Swedish only), called Naomi Klein’s Nudity Shock: Exclusive Exposure: Everything on the Empress’ New Clothes (my [quick] translation).”

Bonus libertarian material: Former guest blogger David Gordon has a nice takedown of Thaler and Sunstein’s Nudge, their defense of “libertarian paternalism.” See also this exchange between Thaler and Mario Rizzo.

Me on Benkler

| Peter Klein |

Here is my review of Yochai Benkler’s The Wealth of Networks: How Social Production Transforms Markets and Freedom (Yale University Press, 2006). It will appear in the Fall 2008 issue of The Independent Review. Benkler has written a fine book, though I have some reservations, as explained in the review.

Edinburgh Business School to Buy Adam Smith’s House

| Peter Klein |

How would you like to take economics classes in Adam Smith’s house? Edinburgh Business School students will have the pleasure after the school completes its purchase of Panmure House, Adam Smith’s home from 1788 to 1790. Smith was born in nearby Kirkaldy and spent much of his academic career in Glasgow, but lived in Edinburgh on several occasions and was a prominent member of Edinburgh society.

Some commentators find it ironic that the house’s current owner, Edinburgh’s City Council, is selling to the university rather than accept a higher, competing bid from a private citizen. So much for the free market! But, as a careful reading of Smith reveals, Smith was hardly an advocate for unrestricted laissez-faire, supporting substantial public expenditures on infrastructure and education as well as the legal system and national defense (see David Gordon and Gavin Kennedy).

Manne on Ideology and the Law-and-Economics Movement

| Peter Klein |

Josh Wright has written a thoughtful and informative series on the future of law and economics (1, 2, 3, 4). Key issues include the increasing formalism of L&E scholarship, the place of L&E within law schools (as opposed to economics departments), and the influence of L&E on legal practice and public policy.

The latest entry focuses on a response to Josh by Henry Manne, the founder of the modern law-and-economics movement (and, I might add, a regular reader of O&M). Manne argues that ideology, more than genuine scientific disagreement, explains the often-hostile reaction to L&E within the legal establishment, a theme we’ve explored in several posts (1, 2, 3, 4, 5).

I think that the major issues are now, as they were fifty years ago, mainly ideological, and I believe that the causes forcing L&E out of the law schools today are the very same ones that operated to prevent my getting better jobs in the 1960s and for most senior law professors to think that what I was advocating was sheer nonsense, “to the right of Genghis Kahn,” as they used to be so stupidly amused at repeating ad nauseum. They were protecting their intellectual investment in skills and ideology against the threat of a new paradigm in which they could not share the rents, and I do believe that that is exactly what is still happening. While you and I see enormous social benefits from a legal system based on the idea of property rights and their protection, all they see is less role for the government and themselves. Perhaps this acts at an unconscious level, but it unmistakably is at work whatever the source of the peculiar leftist ideology of most academics.

What I am saying is that it is impossible to separate completely a discussion of the role of L&E in legal education from the ideological aspects of the subject. I honestly believe that at some level the turn of L&E to econometrics and empirical work is a flight from the implications of a thoroughgoing Alchianesque kind of economics. Perhaps that is even more clear with the current popularity of Behavioral Economics, and of late I even notice in the literature a somewhat open attack on the very idea of freedom of contract. I do not think these developments are accidental or random; I believe that they are inherent in the very structure of modern universities and law schools.

Turgot and What Might Have Been

| Peter Klein |

As a Francophile and Turgot enthusiast I direct you to Frédéric Sautet’s remarks on today’s anniversary of Turgot’s dismissal by the French crown:

May 12, 1776 was one of the saddest days for France. It was the day Louis XVI removed A.R.J. Turgot from office. Turgot was the Minister of Finance of France, the greatest French economist of the 18th century, and a key figure of the French enlightenment (he was a close friend of Condorcet, and Voltaire came to his rescue). He had a great sense of duty, freedom, and civilization. Turgot was too successful, so to speak, in his economic reforms and in the fiscal discipline he imposed on the finances of the French Crown. He fell because he wanted to go too far in the removal of confiscatory taxes (la taille and la corvée), the deregulation of commerce and industry, and the abolition of privileges many guilds and others possessed at the time (e.g. les droits féodaux). Turgot is perhaps the greatest reformer the world has ever seen. If Louis XVI had trusted his Minister of Finance to the end, it is likely that the French Revolution would not have taken place.

Note that Turgot even had his own castle. Ricardo was almost certainly wealthier, though. Böhm-Bawerk was also a fine Minister of Finance.

A Question for the Pigou Club

| Peter Klein |

A few years ago Greg Mankiw coined the term Pigou Club, a label for those (like himself) who advocate higher Pigouvian taxes on gasoline consumption and other high-carbon-footprint activities. Personally, I don’t find the Pigouvian analysis very convincing, in this or the more general case. First, the idea of efficient Pigouvian taxes and subsidies ignores subjective value and the Hayekian knowledge problem. How can government officials possibly choose tax or subsidy amounts that compensate for the actual harm suffered by, or benefit enjoyed by, all possible third parties for all activities generating externalities? The problem is several orders of magnitude more complex than what is typically described in the the textbooks. As a mechanism design problem, it is as difficult as the general socialist calculation problem itself (and you know how I feel about that). Second, the Pigouvian approach ignores comparative institutional analysis altogether. What are the efficiency consequences of establishing, empowering, and funding a government agency to compute and implement Pigouvian taxes and subsidies? Where will the tax revenues go? How will the subsidies be financed? What are the effects of these distortions?

My preference is to treat “negative externalities” as torts, with property titles assigned by the homesteading principle rather than Coasean wealth maximization criteria. (Essentially the Rothbardian view.)

But my main beef with today’s Pigouvians is that they cherry-pick a case here and there — taxes on gasoline, primarily — without fully pursuing the implications of the analysis. If increasing gasoline taxes is efficient, why stop there? What other market failures should the state be empowered to remedy? Here’s my question, specifically:

Please name the activities you believe deserve Pigouvian subsidies. For each activity provide the efficient subsidy amount, explain how this was calculated, and say how the revenues should be raised.

I don’t recall Mankiw discussing Pigouvian subsidies on his blog. Greg, help us out!

Are Brand Names a Modern Phenomenon?

| Peter Klein |

Not at all, says Gary Richardson, in a new NBER paper, “Brand Names Before the Industrial Revolution.” Branding has long been the target of largely uncomprehending critique from the likes of Veblen, Galbraith and sociologists such as Daniel Bell but its role in maintaining quality and reliability and securing contractual performance is now generally understood. Importantly, shows Gary (my former grad-school classmate), the use of seller-specific markers was widespread even before the Industrial Revolution and played an important role in facilitating the emergence of long-distance trade:

In medieval Europe, manufacturers sold durable goods to anonymous consumers in distant markets, this essay argues, by making products with conspicuous characteristics. Examples of these unique, observable traits included cloth of distinctive colors, fabric with unmistakable weaves, and pewter that resonated at a particular pitch. These attributes identified merchandise because consumers could observe them readily, but counterfeiters could copy them only at great cost, if at all. Conspicuous characteristics fulfilled many of the functions that patents, trademarks, and brand names do today. The words that referred to products with conspicuous characteristics served as brand names in the Middle Ages. Data drawn from an array of industries corroborates this conjecture. The abundance of evidence suggests that conspicuous characteristics played a key role in the expansion of manufacturing before the Industrial Revolution.

See also Gary’s EH.Net Encyclopedia entry on guilds.

Defending the Undefendable, Online

| Peter Klein |

I forgot to mention that Defending the Undefendable is also available in a free online edition. Text and pictures!

Table of contents below the fold: (more…)

Defending the Undefendable

| Peter Klein |

One of the greatest influences on my intellectual development (such as it is) was Walter Block’s Defending the Undefendable: The Pimp, Prostitute, Scab, Slumlord, Libeler, Moneylender and Other Scapegoats in the Rogue’s Gallery of American Society. Yes, you read that right. It’s a brilliant polemic on the benefits of peaceful, voluntary exchange, using the most outrageous and provocative examples to illustrate the gains from trade. And oh, the cartoons! My favorite, appearing in the chapter on saving, shows a half-crazed, miserly sort running his fingers through a large pile of gold coins, shouting to his wife, “Lip up, will ya’, Edith? You knew I wasn’t a Keynesian when you married me!”

First published in 1976, the book has just been reissued by the Mises Institute. Get one today and give yourself the same experience as Hayek:

Looking through Defending the Undefendable made me feel that I was once more exposed to the shock therapy by which, more than fifty years ago, the late Ludwig von Mises converted me to a consistent free market position. . . . Some may find it too strong a medicine, but it will still do them good even if they hate it. A real understanding of economics demands that one disabuses oneself of many dear prejudices and illusions. Popular fallacies in economic frequently express themselves in unfounded prejudices against other occupations, and showing the falsity of these stereotypes you are doing a real services, although you will not make yourself more popular with the majority.

See also Block’s 1994 article, “Libertarianism and Libertinism,” which clarifies some misconceptions about the argument. It appeared in the Journal of Libertarian Studies back when yours truly was assistant editor.

Economics and the Rule of Law

| Peter Klein |

This week’s Economist features a summary of recent economic controversies about the rule of law (thanks to Fabio Chaddad for the pointer). There is near-universal consensus among specialists in economic history and economic growth that the legal rules — and institutions more generally — “matter,” though the precise mechanisms are in dispute, and aspects of the institutional environment such as the quality of legal rules are difficult to measure consistently across societies and over time. We’ve touched on the closely related “legal origins” debate before. As with that controversy, the arguments in this one have become more subtle and complex in the last decade. As the Economist notes:

[A]s an economic concept the rule of law has had a turbulent history. It emerged almost abruptly during the 1990s from the dual collapses of Asian currencies and former Soviet economies. For a short time, it seemed to provide the answer to problems of development from Azerbaijan to Zimbabwe, until some well-directed criticism dimmed its star. Since then it has re-established itself as a central concept in understanding how countries grow rich — but not as the panacea it once looked like.

The Economist piece focuses on the distinction between “thick” and “thin” understandings of the rule of law. (more…)

State-Enforced Cartels

| Peter Klein |

Theory and evidence suggest that firms cannot form effective cartels on the free market. So, when producers wish to cartelize, they naturally turn to the state for help. Pennsylvania’s recent decision to forbid dairies from advertising hormone-free milk provides a vivid example. “It’s kind of like a nuclear arms race,” said State Agriculture Secretary Dennis C. Wolff in November. “One dairy does it and the next tries to outdo them. It’s absolutely crazy.” Right, next thing you know firms will be lowering prices, increasing output, improving quality — who knows what else! If only they could agree not to compete. . . . (Andrew Samwick helpfully declared Wolff’s office a “Microeconomics Free Zone.”)

The classic example of state-enforced cartelization is, of course, the National Industrial Recovery Act of 1933. The Depression, argued President Roosevelt, was exacerbated by excessive competition among firms, so firms must be compelled to form cartels to keep nominal prices and wages high (exactly the opposite, unfortunately, of what was needed to reduce unemployment). Despite a massive propaganda campaign to enforce participation the NIRA cartels largely fell apart by early 1934. Jason Taylor and I have a new paper exploring the role of expectations and enforcement in the collapse of the NIRA. Abstract below the fold: (more…)

Essay Contest on Property Rights

| Peter Klein |

My co-blogger, an enthusiast for the Coase-Alchian-Demsetz-Cheung-Barzel property-rights approach, will appreciate the topic for this year’s Sir John M. Templeton Fellowships Essay Contest, sponsored by the Independent Institute:

For decades social critics in the United States and throughout the Western world have complained that “property” rights too often take precedence over “human” rights, with the result that people are treated unequally and have unequal opportunities. Inequality exists in any society. But the purported conflict between property rights and human rights is a mirage — property rights are human rights.

— Armen Alchian, “Property Rights,” in The Concise Encyclopedia of Economics

Are property rights human rights? How are they related? What are their similarities and differences? If property rights are human rights, why have they enjoyed fewer legal protections and intellectual champions than other human rights?

The contest is for college students and “young” college professors (sorry Nicolai).

Recent Comments