Posts filed under ‘Financial Markets’

The Chris Dodd Strangle Entrepreneurship Act, or, Where’s Creative Destruction When You Need It?

| Craig Pirrong |

Back in January, Tool Time star Tom Friedman lamented that Mr. Cool had turned his back on the “amazing, young, Internet-enabled, grass-roots movement he mobilized to get elected.” Friedman all but begged Obama to spur entrepreneurship and innovation:

Obama should launch his own moon shot. What the country needs most now is not more government stimulus, but more stimulation. We need to get millions of American kids, not just the geniuses, excited about innovation and entrepreneurship again. We need to make 2010 what Obama should have made 2009: the year of innovation, the year of making our pie bigger, the year of “Start-Up America.”

How’s that working out for you, Tom? With all the taxes on capital in the health care law, and the implicit tax on business expansion in the law (e.g., insurance mandates on companies with more than 50 employees), and all the taxes to come (there are murmurs of a VAT), it is becoming the year of Shut-Down America. The whole Obama program is poison to entrepreneurship.

And that’s just the start. Dodd’s banking bill explicitly targets startups:

Dodd’s bill would require startups raising funding to register with the Securities and Exchange Commission, and then wait 120 days for the S.E.C. to review their filing. A second provision raises the wealth requirements for an “accredited investor” who can invest in startups — if the bill passes, investors would need assets of more than $2.3 million (up from $1 million) or income of more than $450,000 (up from $250,000). The third restriction removes the federal pre-emption allowing angel and venture financing in the United States to follow federal regulations, rather than face different rules between states.

And just what are the apparatchiks in the SEC going to do in that 120 days? Just what knowledge and expertise can they bring to bear in evaluating the funding plans? The question answers itself; this adds costs and delay, for no perceivable benefit. And what reason is there to restrict the free flow of capital from consenting adults with over $1mm to startups? (more…)

Are Index Funds Immoral?

| Lasse Lien |

If I had money to invest, which I don’t, I would probably invest via an index fund. I know just enough empirical finance to realize that beating an index fund is very difficult (impossible according to some) unless you are either very lucky or an inside trader. The reason is of course the efficient markets hypothesis. The stock market factors in all relevant information at lightning speed and without bias. However, this can only be so because there are enough investors that do not invest via index funds. If everyone did, the pricing would not be informative at all. One might argue that index fund investors are free riders on those that do fundamental analysis, and a sinister threat to the very market efficiency that they thrive on.

I guess in equilibrium one would expect index investing to increase until market pricing is so inefficient that the expected returns from it is driven down to around the levels of the best alternative.

Financial Constraints and Innovation

| Peter Klein |

Why are firms in poor countries less productive than firms in rich countries? Is it lack of technical know-how? Poor infrastructure? Insufficient human capital? Weak intellectual-property protection? Actually, the evidence suggests a more prosaic explanation: financial constraints.

One stylized fact that appears from emerging markets and transition economies . . . is that foreign owned fi rms tend to be more productive than domestically owned firms. . . . To the extent that foreign owned fi rms embody the technological frontier, one can interpret this fact as suggesting that some forces prevent domestically owned firms from emulating the best practices and techniques. . . .

We show that a fi rm’s decision to invest into innovative and exporting activities is sensitive to fi nancial frictions which can prevent fi rms from developing and adopting better technologies. Furthermore, we demonstrate that in a world without financial frictions, innovation and exporting goods are complementary activities. Thus, easing financial frictions can have an ampli ed eff ect on firms’ innovation eff ort and consequently the level of productivity. However, as financial frictions become increasingly severe, these activities become eff ectively substitutes since both exporting and innovation rely on internal funds of fi rms.

That’s from “Financial Constraints and Innovation: Why Poor Countries Don’t Catch Up” by Yuriy Gorodnichenko and Monika Schnitzer. One implication is that diversified firms, whose operating units have access to the firm’s internal capital market, have particular advantages in developing countries, an argument explored in several papers by Khanna and Palepu (e.g., here). In the US, these advantages may not outweigh other drawbacks of unrelated diversification.

Mannepalooza at Austrian Scholars Conference

| Peter Klein |

Tune in here at 3:45 EST today for a live broadcast of the ASC session, “The Contributions of Henry G. Manne,” organized by yours truly. Panelists include me, Alexandre Padilla, Richard Vedder, Thomas DiLorenzo, and Henry Manne. And buy your copy of the Collected Works.

Update: audio files are now available: Klein, Padilla, Vedder, DiLorenzo, Manne.

Org. Structure and Diversification

| Peter Klein |

The March 2010 issue of the Journal of Industrial Economics has just come out, and it features my paper with Marc Saidenberg, “Organizational Structure and the Diversification Discount: Evidence from Commercial Banking.” I’m quite happy with the paper, which went through many rounds of revision and consumed a great deal of time and energy. I blogged the details earlier. The published version is behind a firewall; if you can’t get through I’d be happy to mail you a copy.

Gene Fama’s Autobiography

| Peter Klein |

Here’s an autobiographical essay by Gene Fama written for the Annual Review of Financial Economics. Fama’s work on agency theory (with Mike Jensen) and on corporate finance (with Ken French) should be of particular interest to O&Mers, though some may disagree with his introductory claim that “[f]inance is the most successful branch of economics in terms of theory and empirical work, the interplay between the two, and the penetration of financial research into other areas of economics and real-world applications.”

Here’s an autobiographical essay by Gene Fama written for the Annual Review of Financial Economics. Fama’s work on agency theory (with Mike Jensen) and on corporate finance (with Ken French) should be of particular interest to O&Mers, though some may disagree with his introductory claim that “[f]inance is the most successful branch of economics in terms of theory and empirical work, the interplay between the two, and the penetration of financial research into other areas of economics and real-world applications.”

Fama’s Chicago-Booth colleagues add the following note about Fama’s institutional leadership, presumably directed at today’s Fama-bashers:

Rather than rest on his laurels or impose his own views on the group, Gene has always sought the truth, even when it appeared at odds with his own views. . . . The current finance group at Chicago includes a diverse set of people who specialize in all areas of modern finance including, behavioral economics, pure theory, and emerging, non-traditional areas such as entrepreneurship and development that were unheard of when Gene arrived at Chicago. Contrary to the caricatured descriptions, there is no single Chicago view of finance, except that the path to truth comes from the rigorous development and confrontation of theories with data.

Price Level Shocks, uhm, Screwed Up Relative Prices, and Organization

| Craig Pirrong |

Peter’s post on the relation between inflation, vertical integration, and markets brings a couple of other thoughts to mind.

First, and most importantly, the number and characteristics of markets are endogenous too, and respond to changes in the amount of uncertainty in the environment, including the amount of uncertainty resulting from monetary shocks that (in Sherwin Rosen’s unforgettable in-class phrase) “f*ck up relative prices.” In particular, the number and variety of futures markets depends on the amount of uncertainty. The big boom in the creation of futures markets in the 1970s corresponds with, and was arguably caused by, the coincident inflation of that period, and the associated volatility in relative prices.

Second, although Peter’s point, and previous research, focuses on the implications of inflation on organizational choices and market vs. firm choices, in the current environment it is worthwhile pondering the implications of deflation. Certainly we have more research on the effect of inflation on the variability of relative prices due to our more recent inflationary experiences, and this was a major source of concern about inflation among Austrians, but the current situation makes it worthwhile to consider the effects of deflation on the pricing system, and firms’ responses to that.

Perhaps an examination of Japanese experience since 1990 would be worth some in-depth analysis.

Personally I am torn as to whether inflation or deflation is the greater risk in the near to medium term. The huge monetary overhang in the US and around the world (resulting from quantitative easing and other extraordinary monetary policies), and the inability of the Fed to commit credibly to drain reserves from the system when money demand picks up make me believe that it will be hard to avoid a burst of inflation. But all current indicators point to flat or declining prices.

It is hard to see things ending in a Goldilocks moment — just right. Thus, it is likely that that there will be a shock to prices generally, arguably a large one, and that this will disrupt relative prices for a variety of reasons. (Including, notably, the very likely case where these price level shocks lead to government policy interventions that distort relative prices.)

Thus, Peter’s research program may be rejuvenated, courtesy of the Fed, ECB, the Chinese Central Bank, etc. It is indeed an ill wind that blows nobody any good.

Josh Lerner on Public Policy Toward Entrepreneurship

| Peter Klein |

Speaking of public entrepreneurship, here’s an interview with Josh Lerner about his new book Boulevard of Broken Dreams: Why Public Efforts to Boost Entrepreneurship and Venture Capital Have Failed — and What to Do About It (Princeton, 2009). Excerpt:

There are two well-documented problems that can derail government programs to boost new venture activity. First, they can simply get it wrong: allocating funds and support in an inept or, even worse, a counterproductive manner. Decisions that seem plausible within the halls of a legislative body or a government bureaucracy can be wildly at odds with what entrepreneurs and their backers really need. . . .

Economists have also focused on a second problem, delineated in the theory of regulatory capture. These writings suggest that private and public sector entities will organize to capture direct and indirect subsidies that the public sector hands out. For instance, programs geared toward boosting nascent entrepreneurs may instead end up boosting cronies of the nation’s rulers or legislators. The annals of government venturing programs abound with examples of efforts that have been hijacked in such a manner.

Thanks to Ross Emmett for the tip.

Socialist Calculation Meets the OTC Markets

| Craig Pirrong |

A new Federal Reserve Bank of NY staff report by Darrell Duffie, Ada Li, and Theo Lubke, “Policy Perspectives on OTC Derivatives Market Infrastructure” has received a lot of attention in the press.

There are some good things in the paper. Notably, it is suitably cautionary about the potential systemic risks posed by central counterparties, and the consequent need for prudential regulation thereof. It also makes a good case for data repositories, and for the role of the Fed and other government agencies in reducing the costs that intermediaries incur to coordinate risk-reducing actions, such as portfolio compression and improvements in the process of confirming deals.

But overall the paper is extremely disappointing. Its tone is Olympian and prescriptive. The word “should” is used 61 times 21 pages of text (that includes several space-eating tables and charts).

This is extremely dangerous because these prescriptions and dictates are not based on a a rigorous analysis of costs and benefits. Most disturbingly, there is virtually no discussion whatsoever of the informational demands inherent in the prescriptions. We’re told that regulators should set the right capital and collateral requirements on non-cleared deals, and that CCPs should maintain “high collateral standards.” (more…)

A Tale of Two Papers, or, Humpty Dumpty Writes About Exchanges

| Craig Pirrong |

The American Economic Association/American Finance Association Meetings are just about over. I made a quick trip there to comment on a paper. Upon returning home, I downloaded a couple of the papers presented that seemed of interest. Good call on one, bad call on the other.

The bad one is “Centralized versus Over The Counter Markets” by Viral Acharya of LBS and NYU, and Alberto Bisin of NYU. Although the motivation of the paper is admirable, the execution is execrable, and is representative of a lot of what is wrong in the profession.

The motivation is to compare the efficiencies of alternative ways of organizing derivatives trades: centralized exchanges and over-the-counter (OTC) markets. Great. Big question. I’ve written a lot about it, and would be very interested in seeing other takes thoughtful on the subject.

The paper concludes that organized exchanges are (constrained) first best efficient, and more efficient than OTC markets. A quick review of the paper makes it clear, however, that they’ve rigged the game to produce that result. (more…)

The Collected Works of Henry Manne

Via Geoff Manne, a description and ordering information for the new Collected Works of Henry Manne, produced by Liberty Fund. A great collection of scholarly articles, reviews, and shorter popular pieces divided into three volumes, “The Economics of Corporations and Corporate Law,” “Insider Trading,” and “Liberty and Freedom in the Economic Ordering of Society.” Order your copy today!

A Piece on Financial Derivatives Regulation in FT Alphaville

| Craig Pirrong |

FT Alphaville, one of the Financial Times’ blogs, kindly asked me to contribute a guest post on the financial-markets regulation legislation currently working it’s way through Congress. (Thanks, Stacy-Marie.) Here’s what I wrote:

Lawmakers in DC are due to resume debate on major financial-reform legislation currently working its way through the US House of Representatives. One closely watched aspect of that debate is sweeping overhaul of over-the-counter derivatives markets. Lawmakers are pushing to mandate that most derivatives be centrally cleared and traded either on exchanges or swap execution facilities. Professor Craig Pirrong of the University of Houston discusses some of the proposals.

In attempting to impose standardization on the ways that derivatives are traded, and derivatives counterparty risks are managed and shared, the legislation reflects a one-size-fits-all mentality (not to say fetish) that is sadly typical of most legislative attempts to construct markets. These standardization directives fail to recognize that market participants are diverse, with diverse needs and preferences, and that as a consequence, it is desirable to have diverse trading mechanisms to accommodate them. (more…)

Boeing and the Higgs Effect

| Peter Klein |

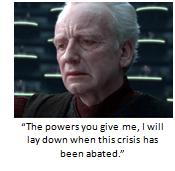

In their calls for greatly expanding the Federal Reserve System’s and Treasury Department’s roles in the economy, Chairman Bernanke, Secretaries Paulson and Geithner, and their academic enablers have repeatedly emphasized the temporary nature of these “emergency” measures. “History is full of examples in which the policy responses to financial crises have been slow and inadequate, often resulting ultimately in greater economic damage and increased fiscal costs. In this episode, by contrast, policymakers in the United States and around the globe responded with speed and force to arrest a rapidly deteriorating and dangerous situation,” said Bernanke in September. Yeah, no kidding. But, we are assured, the basic structure of our “free-enterprise” system remains soundly in place.

However, as Bob Higgs has taught us, “temporary,” “emergency” government measures are never that. Indeed, virtually all the major, permanent expansions of US government in the twentieth-century resulted from supposedly temporary measures adapted during war, recession, or some other “crisis,” real or imaginary. Cousin Naomi’s “disaster capitalism” thesis is exactly backward: it is socialism, or interventionism, that thrives during the crisis, and Washington, DC never looks back. I mean, does anyone seriously believe that the Fed will deny, or give back, the authority to purchase whatever financial assets it wishes at some future date when it deems the crisis officially “over”? Will the Treasury credibly commit never again to purchase equity or guarantee debt or otherwise protect some major industrial or financial firm after the economy returns to “normal”? Not a chance. Everything the authorities have done in the last two years to deal with this “emergency” will become part of the federal government’s permanent tool kit.

However, as Bob Higgs has taught us, “temporary,” “emergency” government measures are never that. Indeed, virtually all the major, permanent expansions of US government in the twentieth-century resulted from supposedly temporary measures adapted during war, recession, or some other “crisis,” real or imaginary. Cousin Naomi’s “disaster capitalism” thesis is exactly backward: it is socialism, or interventionism, that thrives during the crisis, and Washington, DC never looks back. I mean, does anyone seriously believe that the Fed will deny, or give back, the authority to purchase whatever financial assets it wishes at some future date when it deems the crisis officially “over”? Will the Treasury credibly commit never again to purchase equity or guarantee debt or otherwise protect some major industrial or financial firm after the economy returns to “normal”? Not a chance. Everything the authorities have done in the last two years to deal with this “emergency” will become part of the federal government’s permanent tool kit.

Today’s WSJ has a good example of Higgs’s ratchet effect, a front-pager on Boeing’s dependence on export loan guarantees from the Export-Import Bank, a federal government agency created in — you guessed it — 1934, as a temporary agency to deal with the Great Depression. “No company has deeper relations with Ex-Im Bank than Chicago-based Boeing. Without Ex-Im, aviation officials say, Boeing this year could have been forced to slash production, endangering hundreds of U.S. suppliers, thousands of skilled American jobs and billions of dollars in export contracts.” Bank official Bob Morin is described as “Ex-Im Bank’s rainmaker. His Boeing deals accounted for almost 40% of the bank’s $21 billion in business last year. To help Boeing through the credit crunch, his team has spent the past year developing government-backed bonds that promise to raise billions.” So, a massive industrial-planning apparatus, supposedly born during a temporary crisis, lives on as the lifeblood of a huge, politically connected US company.

Thank goodness all that money flowing to Goldman Sachs is only temporary!

Update: Here’s a short Higgs piece from 2000 on the Ex-Im Bank, appropriately titled “Unmitigated Mercantilism.”

Lynch ‘Em

| Craig Pirrong |

I’ve had several calls from reporters asking my opinion on the Lynch Amendment to Barney Frank’s derivatives-regulation bill. For some reason, Forrest Gump pops into my head every time that question is asked. You know, the part where he says “stupid is as stupid does.”

As I am sure you all know, the amendment, introduced by New Jersey representative Stephen Lynch, imposes restrictions on the ownership and control of the clearinghouses that the Frank bill will require the vast bulk of derivatives to be traded through. The amendment imposes similar restrictions on ownership of exchanges and swap execution facilities.

Specifically, the amendment defines a class of “restricted owners” that includes swap dealers and major swap participants, and limits the amount of a clearinghouse (or execution facility or exchange) that these restricted owners can own or control collectively to 20 percent. The justification for this limitation is to reduce conflicts of interest, the specific nature of which are not identified.

This represents yet another example of Congressional micromanagement of the organization and governance of financial institutions. In my view, it is incredibly wrong-headed. (more…)

Financing Constraints and Entrepreneurship

| Peter Klein |

Speaking of banks, here’s a very good survey of the entrepreneurship literature on financing constraints by William Kerr and Ramana Nanda, just out from NBER. From the introduction:

The first research stream considers the impact of financial market development on entrepreneurship. These papers usually employ variations across regions to examine how differences in observable characteristics of financial sectors (e.g., the level of competition among banks, the depth of credit markets) relate to entrepreneurs’ access to finance and realized rates of firm formation. The second stream employs variations across individuals to examine how propensities to start new businesses relate to personal wealth or recent changes therein. The notion behind this second line of research is that an association of individual wealth and propensity for self-employment or firm creation should be observed only if financial constraints for entrepreneurship exist.

These two streams of research have remained mostly separate literatures within economics, driven in large part by the different levels of analysis. Historically their general results have been mostly complementary. More recently, however, empirical research using individual-level variation has questioned the extent to which financing constraints are important for entrepreneurship in advanced economies. This new work argues that the strong associations between the financial resources of individuals and entrepreneurship observed in previous studies are driven to large extents by unobserved heterogeneity rather than substantive financing constraints. These contrarian studies have led to renewed interest and debate in how financing environments impact entrepreneurship in product markets.

Further My Last

| Craig Pirrong |

My previous post on the Acharya et al (AEFLS) assertion of the purported externality in bilateral OTC markets focused on whether there was actually an unpriced “bad.” I judged otherwise based on the fact that credit and counterparty risks are repriced repeatedly (and ruthlessly).

There is another reason to reject their analysis. It should be incumbent on one who justifies the existence of an externality to justify a particular policy to (a) identify the transactions costs that preclude internalization of this externality, and (b) demonstrate that their policy would create a net benefit, by, for instance, reducing transactions costs. AEFLS don’t even try to do this (another symptom of the Nirvana fallacy). And when one examines the particulars, it is highly doubtful that the costs of the purported externality are as large as AEFLS insinuate that they are.

The AEFLS story is that contracts between two counterparties to an OTC derivatives deal impose costs on other market participants, notably, the firms’ other counterparties to earlier derivatives deals, and the counterparties’ counterparties, and on and on. OTC market participants don’t take these costs into account, trade too much, and create too much risk.

Which raises the Coase Question: if these costs are so large, why don’t the affected parties craft a solution that mitigates them? If, as AEFLS argue, a central counterparty would reduce these costs, why don’t the affected parties create one to internalize the externality and enhance their welfare? (more…)

Nirvana Is Just a Band

| Craig Pirrong |

Last week I wrote about one justification for exchange trading and clearing mandates in derivatives markets — the market power argument. This week I’ll examine another argument, and render a similarly skeptical verdict.

In a chapter of Restoring Financial Stability, Viral Acharya, Rob Engle, Steve Figlewski, Anthony Lynch and Marti Subrahmanyam argue that bilateral transactions in OTC derivatives markets involve an externality. Their argument is not stated that clearly, but FWIW here it is verbatim:

[A]ll OTC contracts . . . feature collateral or margin requirements, wherein counterparties post a deposit whose aim is to minimize counterparty risk. The deposit is marked to market daily, based on fluctuations in the value of the underlying contract and the creditworthiness of the counterparties . . . . The difficulty, however, is that such collateral arrangements are negotiated on a bilateral basis. Parties in each contract do not take full account of the fact that counterparty risk they are prepared to undertake in a contract also affects other players; indeed, they often cannot take account of this counterparty risk externality in an OTC setting, due to inadequate transparency about the counterparty’s positions and its interconnections with the rest of the market. While bilateral collateral arrangements do respond to worsening credit risk of a counterparty, such response is often tied to agency ratings, which are sluggish in capturing credit risk information and potentially inaccurate.

An externality means that some cost or benefit is not priced. By invoking the concept of externality Acharya et al (“AEFLS”) are asserting that something — a bad in this instance — isn’t priced. They are a very vague on just what this is, but here’s my interpretation of what they mean.

A firm that has already entered into financial contracts affects the risk exposure of its existing counterparties when it enters into new deals. A firm that has a large number of commitments outstanding can enter into additional contracts that substantially increase its riskiness, thereby harming the incumbent counterparties. The cost imposed on these incumbent counterparties isn’t, in this telling, priced. (more…)

Fed Independence and Comparative Institutional Analysis

| Peter Klein |

I’ve written before on Fed “independence” and why I don’t support it. The vast majority of economists, especially the more prominent ones, are strongly in favor of independence and against Congressional attempts to limit the Fed’s discretion in monetary and regulatory policy. The standard argument is that a “politicized” — i.e., accountable — central bank will be more expansionary than an unaccountable central bank, assuming that credit expansion affects output first and prices (inflation) second. Last week’s piece by Kashyap and Mishkin follows this script. On the face of it, this seems absurd, as — to take only the most obvious example — the Greenspan-Bernanke “independent” Fed has been the most expansionist in modern history, with a ballooning money supply throughout the 2000s and near-zero interest rates and injections of giggledysquillions of dollars into the banking sector in the last 18 months. The independence crowd cites cross-country studies finding a negative correlation between central-bank independence and inflation, but these studies are controversial (many problems with reverse causation, omitted variables, sample size, etc.).

My question today is different: Where, in those arguments, is the comparative institutional analysis? After all, in policy analysis, we are always comparing imperfect alternatives. We try to avoid the Nirvana fallacy. Craig does this in his post below, asking if a centralized financial regulator would be less bad than the competing regulatory bodies we have today.

But the macroeconomists entirely ignore this problem. Consider Mark Thoma’s defense of independence:

The hope is that an independent Fed can overcome the temptation to use monetary policy to influence elections, and also overcome the temptation to monetize the debt, and that it will do what’s best for the economy in the long-run rather than adopting the policy that maximizes the chances of politicians being reelected.

This naive wish is simply that, a hope. Where is the argument or evidence that a wholly unaccountable Fed would, in fact, “do what’s best for the economy in the long-run”? What are the Fed officials’ incentives to do that? What monitoring and governance mechanisms assure that Fed officials will pursue the public interest? What if they have private interests? Maybe they’re motivated by ideology. Suppose they make systematic errors. Maybe they’ve been captured by special-interest groups like, oh, I don’t know, the banking industry (duh). To make a case for independence, it is not enough to demonstrate the potential hazards of political oversight. You have to show that these hazards exceed the hazards of an unaccountable, unrestricted, ungoverned central bank. The mainstream economists totally ignore this question, choosing to put a naive faith in the wisdom of central bankers to do what’s right. Guys, have you never heard of public-choice theory?

Just So Stories: Financial Regulation Edition

| Craig Pirrong |

All of the legislative proposals relating to over-the-counter derivatives would impose seismic changes on the way that these instruments are traded, and the performance risks related to them are managed. Indeed, it is fair to say that these proposals, if implemented would dramatically shrink the OTC market, and perhaps destroy it altogether. Under either the House (Frank) or Senate (Dodd) bills, most derivatives would have to be traded on exchanges, and be cleared. (Clearing is a way of mutualizing default risks. At present, default risks in a particular contract are directly limited to the buyer and seller.) (BTW, when you hear “Frank and Dodd” do you think Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac? I do. Does this inspire confidence? Self-answering question.) These efforts are strongly supported by Treasury Secretary Timothy Geithner, CFTC head Gary Gensler, and SEC head Mary Shapiro.

These legislative proposals are clearly predicated on a very strong belief: participants in the derivatives markets routinely chose the wrong institutional arrangements. That this immense market is and was in fact arguably the largest market failure in financial history. (more…)

On the Border*

| Craig Pirrong |

This is my inaugural post as guest blogger here at O&M. I am grateful for the opportunity.

In his very gracious introduction, Peter Klein noted that my research is at the border of finance and industrial organization. Quite true (and indeed, “borderer” is a good description of me overall.)

That border is very, very busy today. Indeed, so much is happening there that it is difficult to keep up. In the aftermath of the financial crisis, Congress and regulators are beavering away on laws and regulations that will completely reshape the organization and regulation of financial markets, and especially of the area of particular interest to me — derivatives.

I anticipate that many of my O&M blog posts will explore these issues, but I’ll start with something very topical. Senator Chris Dodd just yesterday heaved up a 1,136-page proposed financial regulation bill, and one proposal that is attracting considerable attention is his plan to consolidate banking regulators. Dodd is not alone in thinking along these lines. Even before the financial crisis, there were myriad proposals to consolidate various regulators, such as the Securities and Exchange Commission and the Commodity Futures Trading Commission. These have only gained in popularity in light of the crisis.

In the modern financial markets, firms are big and complex, and operate in many markets (defined geographically, or by product). It is difficult to fit a big financial firm into any box. A Goldman Sachs deals in the securities markets and the derivatives markets. So it doesn’t fit comfortably in a securities box, or a derivatives box, so in the current system for regulatory purposes the firm is split into pieces, some of which are put into the securities box and others into the derivatives box (and there are many other boxes too for a big firm like Goldman).

This leads to potential for conflicting regulations, jurisdictional disputes, regulatory arbitrage, and other problems. So, the Dodd proposal — and most of the other consolidation proposals — advocate creating really big boxes, and in the extreme, one big box that regulates everything a financial firm does.

The problems of the seen are well known (though arguably exaggerated). What concerns me are the largely unexamined problems of the as-yet-unseen big-box alternative. (more…)

Recent Comments