Posts filed under ‘– Foss –’

Norway Workshop on Org Econ and Org Capabilities

| Nicolai Foss |

With Nick Argyres, Teppo Felin, and Todd Zenger, I am editing a special issue of Organization Science on “Organizational Capabilities and Organizational Economics: From Opposition and Complementarity to Real Integration.” We received 84 submissions and invited a fair amount of R&Rs. To help improve those R&Rs and to stimulate discussed, we organized, with the (practical) help of Professor Sven Haugland and (financial help) the Norwegian School of Economics and Business Administration, a small workshop that took place this Friday and Saturday (28-29 May) at the magnificent Hotel Solstrand, outside of Bergen. The discussions were informative, high-level, and friendly; the weather behaved (Bergen is the most rainy city in Europe); the food was excellent; etc. A model workshop, in short.

A few key points (I will refrain from commenting on the R&R papers):

- Out of 11 papers, 1 was theoretical, 2 were simulation papers, and the rest were empirical. All creatively brought both capabilities and OE ideas to bear on issues of economic organization (including internal organization).

- I argued that virtually all debate on capabilities and economic organization had been dominated by a “capabilities first” heuristic, in which capabilities are primary and transaction costs were, as it were, second-order (e.g., transaction costs moderate the relation between capabilities and vertical scope). It is time to reverse causality and examine how capabilities emerge from “transacting.”

- Nick Argyres and Todd Zenger presented a paper that followed up on this by showing how capabilities can be understood as reflecting specific investments.

- Nevertheless, there was some skepticism regarding whether it is useful to talk about a debate, not just because of the dominance of the capabilities view in that debate, but also because it was better to consider problems “agnostically” and choose flexibly among the available tools, whether drawn from the capabilities or the TCE toolbox. Michael Jacobides argued this point with so much passion that everyone cracked up when Teppo Felin observed that Michael was more of a high-priest than an agnostic.

- “OE” was generally interpreted as “transaction cost economics”; not a single paper brought agency and property rights issues to bear on these issues.

Add to: Facebook | Digg | Del.icio.us | Stumbleupon | Reddit | Blinklist | Twitter | Technorati

The Unbearable Lightness of Economics (?)

| Nicolai Foss |

The always-helpful Peter suggested “a quick-and-easy Foss blog post,” specifically a post on what sounds like an interesting conference on “Economics Made Fun in the Face of the Economic Crisis,” organized by Jack Vromen and N.E. Aydinonat, at the Erasmus University Rotterdam, 10-11 December 2010. The Call builds up a tension between the emerging econ-made-fun genre (Levitt, Cowen et al.) with its implied view of econ as a universal tool for understanding behaviors and their implications, and the claimed inability of econ to come to grips with the current crisis. You may think what you like of this claimed tension, but Jack Vromen always represents quality, and with keynote speakers like Diana Coyle, Robert Frank, and Ariel Rubinstein, this conference will be fun.

Add to: Facebook | Digg | Del.icio.us | Stumbleupon | Reddit | Blinklist | Twitter | Technorati

The Role of Assumptions in Management Research

| Nicolai Foss |

A striking difference between economics and (most) management research is that while economists are obsessed with the role of assumptions in theorizing, management scholars as a rule don’t seem to spend much time on assumptions, at best tucking them away under “boundary conditions,” and, in general, having rather little patience with “assumptions discussions.” In particular, the eyes of management scholars of the more descriptive (“phenomenological”) stripe glaze over from boredom or inattention when the issue is raised.

Major economists (Samuelson and Friedman come immediately to mind) have written famous methodological papers on assumptions. A significant portion of what passes as “economic methodology” is taken up with the nature and status of assumptions. Prominent philosophers have written on the role of assumptions in economics (e.g., Alan Musgrave, Daniel Hausman). However, I know of not a single paper in management research dedicated to the issue. (more…)

Strategic Entrepreneurship Conference at CBS

| Nicolai Foss |

As many O&M readers will know, “strategic entrepreneurship” has emerged as an exciting new research field in the intersection of, well, strategic management and entrepreneurship. In a very broad (perhaps too broad) reading, the field is taken up with explaining the emergence of essentially entrepreneurial acts of those competitive advantages that are so central to the strategic management field. In recognition of the very close links between the strategic entrepreneurship field and the strategic management field, the Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal was established in 2007 as a sister journal to the Strategic Management Journal.

However, like many other macro management fields, strategic entrepreneurship pays rather little attention to the micro-foundations of the explanation of its macro explanandum, firm-level entrepreneurship. Moreover, the influence of formal structure and organizational control on the discovery, evaluation and implementation of opportunities at the firm level has been remarkably under-researched.

To meet these challenges, I have arranged, assisted by my two highly able PhD students, Stefan Linder and Jacob Lyngsie, a conference, “Strategic Entrepreneurship: Bringing Organization Design and Micro-foundations Into the Field,” to take place at the Copenhagen Business School, 11-12 November 11-12 2010. Keynote speakers include such luminaries as Jeff Hornsby, Bill Schulze, Mike Wright and Shaker Zahra. Peter Klein fans will be pleased to be informed that it is quite likely that he will participate!

Here is the — still quite preliminary — conference site. Submit a paper!

Add to: Facebook | Digg | Del.icio.us | Stumbleupon | Reddit | Blinklist | Twitter | Technorati

Strategy Making and PowerPoint

| Nicolai Foss |

We have blogged more than two dozen times on PowerPoint (here) and at least as many times on pomo (here), never realizing that the two themes are connected. In a recent paper, “Strategy and PowerPoint: An Inquiry into the Epistemic Culture and Machinery of Strategy Making” (forthcoming in Organization Science), the ever-interesting Sarah Kaplan poses the question, “How is PowerPoint engaged in the discursive practices that make up the epistemic culture of strategy making?”

Yes, this does smack of hardcore pomo, and would prima facie seem to be up for hard lashing under the O&M rubric of “Pomo Periscope.” However, upon reading, it turns out that this is highly reasonable, well executed, and meaningful pomo. In a nutshell, Sarah argues that PP is a privileged strategy-making support tool, and that it may usefully be analyzed as a genre. And it matters to strategy making, as suggested in this key passage in the paper:

I show how the affordances of PowerPoint enabled the difficult task of collaborating to negotiate meaning in a highly uncertain environment, creating a space for discussion, making combinations and recombinations possible, allowing for rapid adjustments as ideas evolved and providing access to a wide range of actors, no matter how dispersed over space or time. Yet, I found, these affordances also supported cartographic efforts to draw boundaries around the scope of a strategy, certifying certain ideas and not others, and allowing document owners to include or exclude certain slides or participants and control access to information. Cartography in the world of ideas is similar to cartography of the physical landscape: drawing maps and defining boundaries help people navigate otherwise uncertain terrain. These collaborative and cartographic practices shaped the strategic choices and actions taken in the organization.

Why Are the Dutch So Clean?

| Nicolai Foss |

Folk wisdom holds that people stopped bathing after the fall of the Roman Empire. Thus, it is commonly held that all of Europe was, until recently, quite smelly indeed. Some hold the view that this is still the case.

There were serious exceptions, of course. I cannot resist mentioning a particularly well taken example, reported by the prior of St. Fridswides, John of Wallingford, “who complained bitterly that the Danes bathed once a week, combed their hair regularly, and changed their clothes regularly. The result was that English women were easily seduced by the nice-smelling Danes” (here).

A perhaps better-known example of European cleanliness is that of the Dutch. It is also the most seriously researched example. In the 17th and 18th century, visitors to Holland wondered about Dutch cleanliness, indeed, obsession with hygiene. Some have argued that this, somehow, reflected Dutch Calvinism. No, argue Bas van Bavel and Oscar Gelderblom in “The Economic Origins of Cleanliness in the Dutch Golden Age,” the reason is . . . butter! And here is the explanation (Abstract):

This paper explores why early modern Holland, and particularly its women, had an international reputation for cleanliness. We argue that economic factors were crucially important in shaping this habit. Between 1500 and 1800 numerous travellers reported on the habit housewives and maids had of meticulously cleaning the interior and exterior of their houses. We argue that it was the commercialization of dairy farming that led to improvements in household hygiene. In the fourteenth century peasants as well as urban dwellers began to produce large quantities of butter and cheese for the market. In their small production units women, and their daughters, worked to secure a clean environment for proper curdling and churning. We estimate that, at the turn of the sixteenth century, half of all rural households and up to one third of urban households in Holland produced butter and cheese. These numbers declined in the sixteenth century as peasants sold their land and larger farms were set up. Initially the migration of entire peasant families to towns, the hiring of farmers’ daughters as housemaids, and the exceptionally high consumption of dairy products continued to encourage the habit of regular cleaning in urban households. However, by the mid-seventeenth century the direct link between dairy farming and cleanliness was, for the most part, lost.

Assessing the Critiques of the RBV

| Nicolai Foss |

There is little doubt that the resource-based view, in its various guises and manifestations (e.g., see Gavetti & Levinthal’s distinction between “high church” and “low church” approaches to the RBV), is the dominant perspective in strategic management research. Naturally, all dominant approaches attract critique like flies. This is amplified by the fact that the RBV is still evolving; many things have been unclear (e.g., what exactly is assumed about managerial rationality, the game forms that describe strategic factor markets, the interaction (if any) between factor market and product market behaviors, etc.), and those things that have been reasonably clear (e.g., the RBV’s reliance on competitive equilibrium models) have been controversial. Some of the critiques of the RBV are fairly well-known, for example, the Priem and Butler tautology charge, while other critiques are less generally known.

Given that many of the critiques have basically been around for two decades or more, it is surprising that the first comprehensive treatment of the many critiques of the RBV has just been published — namely Kraaijenbrink, Spender, and Groen’s “The Resource-based View: A Review and Assessment of Its Critiques.” (more…)

Why Academic Freedom?

| Nicolai Foss |

At least in Europe, academic freedom is under siege. Politicians justify their meddling with the fact that universities are (largely) financed by taxpayers’ money, and they are assisted in their meddling by a growing class of bureaucrats in ministries, the EU and increasingly in universities themselves. All this derives legitimacy from a questionable ideology of Mode II research that broadly asserts that most important scientific advance (now) happens in the intersection of disciplines and as a result of collaborative relations between universities and business (here is the Wiki on Mode II).

Given this, it seems necessary to rethink the defense of academia and academic freedom. There is, of course, Polanyi’s application of Hayek’s unplanned order idea in the context of the “republic of science.” However, that argument lacks concreteness and cutting power against those bureaucrats/politicians who wants to intervene just a tiny bit but doesn’t want centrally planned science.

In a recent paper, “Academic Freedom, Private-sector Focus, and the Process of Innovation,” Aghion, Dewatripont, and Stein provide a rationale — derived from property rights economics rather than from considerations of appropriability — for academia. Academia is defined as an organizational form which “represents a precommitment to leave control over the choice of research strategy in the hands of individual scientists” (p. 621) (note that this does not necessarily entail public funding). (more…)

Call for Papers: 4th Int. Workshop on Org. Design

| Nicolai Foss |

The 1960s and 1970s were the heydays of organizational design theory. Since then it has fallen out of favor in organization theory (see this nice paper), mainly surviving in organizational economics. However, solid and important work has been done on organizational design all along by the likes of Lex Donaldsson and Richard Burton (e.g., here). These two gentlemen have, together with George Huber, Dorte Døjbak Håkonsson, and Charles Snow, organized the “4th International Workshop on Organizational Design,” to take place at Aarhus University’s School of Business, 29-31 May 2010. Here is the Call for Papers.

Product and Factor Markets in the RBV

| Nicolai Foss |

It is often argued that firm strategy is fundamentally rooted in various imperfections. Strategic management has long been characterized by an intellectual division of labor in which the resource-based view handled (strategic) factor market imperfections and various positioning approaches took care of product market imperfections. This dichotomy is beginning to break down. Two recent papers, one a theory of science-based piece, the other a theory piece, discuss the product/factor market dichotomy and show why it is problematic.

In “Theoretical Isolation and the Resource-based View: Symmetry Requirements and the Separation Between Product and Factor Markets,” Niklas Hallberg and yours truly argue that the RBV treats factor markets as imperfect and product markets as perfect (an approach that we argue is adopted from mainstream economics and its tendency to work with on-off assumptions). We argue that this asymmetry is problematic, as there is a general case to be made for symmetrical assumptions and as it borders on logical inconsistency to assume — within the same model — that one set of markets is perfect and another set is imperfect. The paper isn’t online, but you can email me at njf.smg@cbs.dk for a copy. (Abstract below).

In “Chicken, Stag, or Rabbit? Strategic Factor Markets and the Moderating Role of Downstream Competition,” my CBS (Center for Strategic Management and Globalization) colleague, Dr. Christian Geisler Asmussen, models various deviations from perfect(ly competitive) product markets and shows how these impacts firms’ factor market behaviors and whether they can derive rents from resources purchased on these markets. I believe this is the first systematic study of its kind in the literature (and there are some seriously counter-intuitive findings in it). Very highly recommended! (more…)

Forget Knightian Uncertainty

| Peter Klein |

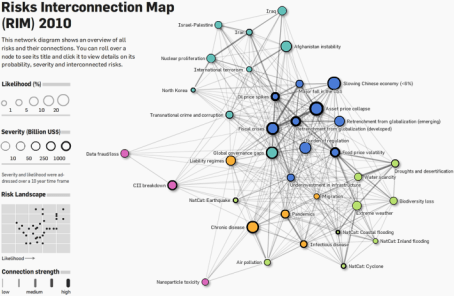

And characterize the world’s uncertain future by listing all possible future events, assigning each a magnitude and probability, linking each event to (causally?) connected events, and sticking them all in a cool interactive graph. I doubt this tells us anything meaningful about the world but it sure is an interesting data visualization exercise! (Datavisualization.ch via Cliff Kuang.)

Cooperation and the Team Problem

| Nicolai Foss |

Alchian and Demsetz’s famous 1972 paper on the team problem and how resolving that problem may call for the “classical capitalist firm” is one of my teaching favorites. Students like the stark, stylized reasoning in the paper, and the team problem is a great way to introduce agency theory, among other things, because it so directly links to what is usually the only piece of game theory they know, namely the PD game.

However, I often experience that some students (particularly those who are following an OB or HRM class) are worried about the reasoning in Alchian and Demsetz, and are not convinced by the argument that it is basically counterfactual (provided they understand this point). I usually also explain that experimental evidence from the public goods literature suggests that cooperativeness declines over time (e.g., here) unless cooperation is backed up by various flanking arrangements (a recent Nobel can now be invoked in support of this).

A recent experimental paper, “Not just hot air: normative codes of conduct induce cooperative behavior,” — written by a German team (Thomas Lauer, Bettina Rockenbach, and Peter Walgenbach), and published in the newly founded Review of Managerial Science — suggests that the verbal framing of a work environment with cooperative connotations may go a long way towards inducing cooperativeness in team settings. In their experiments, the authors implement five “treatments” that differ only in terms of the framing, specifically in the extent to which reference is made to a cooperative firm context.

The basic experimental setup is team production with teams of four members that each have to make decisions on whether to invest or not in a team project. Each unit invested generates a benefit of 1.6 units for the team — but those benefits are divided equally among all team members. In this setting, changes in framing dramatically influence outcomes. I recommend the paper as a fascinating example of the emerging intersection of the economics of the firm, OB, and experimental methods.

Top Scholar Presidents and University Performance

| Nicolai Foss |

Last Friday my unit at CBS, the Center for Strategic Management and Globalization, sponsored a seminar with Dr. Amanda Goodall, the author of Socrates in the Boardroom: Why Research Universities Should be Led by Top Scholars. (For an earlier O&M post on Goodall, see here). Not only did the upper CBS echolons show up (the Research Dean and the President — both highly cited scholars, BTW), but we also had a long and lively discussion. A highly undull seminar!

Goodall’s findings are mainly based on UK data. Roughly, they are that university rankings correlate rather closely with how well-cited the presidents of the relevant universities are, and that there is strong evidence of the research standing of presidents driving university performance. It is hard to understand why this finding (or the book in general) was dissed by Tyler as a “radical attack on economic reasoning” (here).

Anyway, Goodall’s findings made me wonder whether the finding of causality from president/vice-chancellor/BSchool dean generalizes to other university bureaucrats, notably department heads (and deans in general, not just BSchool deans). Many of the things that are being said in the book of the top scholar-president (an example, somebody who defines the standard, an expert etc.) are things that can be said of department heads in well-functioning research universities. Perhaps one of the ways in which university presidents/VCs/deans matter to research performance is by picking good department heads. Also,Goodall claims that top scholars will not have positive performance consequences if they assume the presidency of bad or mediocre universities. She doesn’t really present evidence for this claim, although it does sound intuitive that a Nobel Prize winner is not best placed at the helm of University of Crapville. However, it may be interesting to look at less extreme cases. I do think there are cases of highly regarded scientists helping rather mediocre universities to improve.

Ennen and Richter on Complementarity

| Nicolai Foss |

The notion of complementarity unites a number of the key concerns of this blog: It has been central in Austrian capital theory since Menger, it is key both in (sociological) organization theory (e.g., here) and in organizational economics (e.g., here), and it is of considerable relevance to the explanation of (sustained) performance difference (e.g., here). (In organizational economics and strategic management, complementarity is usually given the specific interpretation of “Edgeworth complementarity“). Complementarity has also helped to link some of these areas (e.g., here and here).

In a paper, “The Whole is More Than the Sum of Its Parts, Or Is It? A Review of the Empirical Literature on Complementarities in Organizations,” in the most recent issue of the Journal of Management, Edgar Ennen and Ansgar Richter of the European Business perform what is probably the first stocktaking of the complementarity literature. It is very well done and in many ways an eye-opener. Of particular interest is their separation of the literature in those that take an “interaction approach,” focusing on specific interaction effects among specific (typically few) elements (e.g., of organization structure) and those that take a “systems approach” and consider the performance outcomes of entire sets of multiple elements. (My own work with Keld Laursen on complementarity falls in the latter category). Here is the abstract:

The concept of complementarity denotes the beneficial interplay of the elements of a system where the presence of one element increases the value of others. However, the conceptual work on complementarities to date has not progressed sufficiently to constitute a theory that would offer specific predictions regarding the nature of the elements that form complementary relationships or the conditions for their emergence. To advance our understanding of complementarities, the authors provide a synoptic review of the empirical studies on this concept in leading journals in management, economics, and related disciplines over the period 1988-2008. The authors find that whether a study provides evidence of complementarities in organizations is at least partially driven by its investigative approach. On the basis of the findings, the authors argue that complementarities are most likely to materialize among multiple, heterogeneous factors in complex systems. Therefore, the absence of complementary relationships between a limited set of individual factors may not negate the possibility of complementarities, but rather point to the need for including further systems-specific factors in the analysis. The authors conclude by providing directions for future theoretical and empirical research and outlining managerial implications of the work.

Designing Internal Organization for External Knowledge Sourcing

| Nicolai Foss |

The heading to this post is the title of an upcoming special issue of the European Management Review, edited by my colleague at the Center for Strategic Management and Globalization at CBS, Dr. Larissa Rabbiosi, in collaboration with Dr. Toke Reichstein (also at CBS) and Prof. Massimo Colombo of the Politecnico di Milano. Two previous workshops organized by Larissa and Toke have dealt with similar issues (here and here). The theme of the workshop may be seen as concerning the organizational dimensions of “absorptive capacity,” a somewhat elusive concept. It has the potential of integrating key aspects of organizational economics with key ideas of the capabilities view. Submit a paper!

Robert Sugden

| Nicolai Foss |

I have become a huge fan of Robert Sugden, an economics Professor at the University of East Anglia and one of the most cited UK economists. Readers of this blog may know Sugden’s work from, for example, his excellent 1986 book, The Economics of Rights, Co-operation, and Welfare, as well as his papers on spontaneous order (e.g., here or here). Much of Sugden’s research lies in the zone of overlap between game theory (mainly experimental game theory and coordination games) and moral and political philosophy, and he is engaged in a constant dialogue with scholars in, or associated with, the classical-liberal tradition, such as Hume, Mill, and Hayek. He is the rare economist who, like Frank Knight, manages to publish in American Economic Review as well as in Ethics.

I am reading through Sugden’s recent publications and recommend the following as being of particular interest to the O&M readership:

- “Can Economics Be Founded on “Indisputable Facts of Experience”? Lionel Robbins and the Pioneers of Neoclassical Economics” — An attack on Robbins’ Essay that may also challenge followers of praxeology.

- “Fraternity: Why the Market Need Not Be a Morally Free Zone“(with Luigino Bruni) — Drawing on the work of a contemporary of Adam Smith, Antonio Genovesi, Sugden and Bruni criticize the idea (reflected in, e.g., Williamson’s distinction between “trust as calculative risk” and “trust proper”) that one can make a distinction between market relationships and genuinely social relationships. Market relationships also have elements of joint intentions for mutual assistance.

- The basis for the latter point can be found in “The Logic of Team Reasoning” which is a case for placing agency at the level of teams, specifically those teams that make use of team reasoning. The basic idea is that when team members reason in this way, they consider which combinations of actions will best promote the team objectives, and choose actions accordingly.

- If the above sounds at variance with classical liberalism (which I don’t think it necessarily is), check out Sugden’s criticism of Thaler and Sunstein (here) or his various critical discussions of the notion of “opportunity” in welfare economics (Sen, Cohen, Roemer) (e.g., here) which are all in the mainstream of classical-liberal thought.

Cultural Economics Conference in Copenhagen

| Nicolai Foss |

My colleague Dr. Trine Bille is the organizer of next year’s “International Conference of the Association of Cultural Economics International” in Copenhagen (CBS). Here is the Call. Submit a paper!

Pomo Periscope XIX: Leiter on Foucault

| Nicolai Foss |

Here is a nice discussion of Foucault by UChicago Law School professor Brian Leiter. It is not a smashing per se, but rather a critical discussion that indicates a central flaw in Foucault’s philosophy. Leiter points to Foucault’s well known discussion of the “pretence” of the “human sciences,” something Foucault seems to explain on the basis of the “influence of economic, political, and moral considerations on their development” (Leiter, p. 16). As Leiter points out, however,

[I]t is now surely a familiar point in post-Kuhnian philosophy of science that the influence of social and historical factors might be compatible with the epistemically special standing of the sciences as long as we can show that epistemically reliable factors are still central to explaining the claims of those sciences. And that possibility is potentially fatal to Foucault‟s critique. For recall that central to Foucault‟s critique is the role that the epistemic pretensions of the sciences play in a structure of practical reasoning which leads agents concerned with their flourishing to become the agents of their own oppression. And the crucial bit of “pretense” is, as we noted earlier, that the human sciences illuminate the truth about how (normal) human beings flourish in virtue of adhering to the epistemic strictures and methodologies of the natural sciences. Recall also that Foucault, unlike Nietzsche, does not contest the practical authority of truth (i.e., the claim of the truth to determine what ought to be done); he rather denies that the claims in question are true or have the epistemic warrant that we would expect true claims to have. So the entire Foucauldian project of liberation turns on the epistemic status of the claims of the human sciences. And on this central point, Foucault has, surprisingly, almost nothing to say beyond raising “suspicion.”

Tracking a Moving Arrow Core

| Nicolai Foss |

As argued by Nelson and Winter in their 1982 book, An Evolutionary Theory of Economic Change, and more explicitly by Winter and Gabriel Szulanski in their 2001 paper, “Replication as Strategy,” many firms leverage their competitive advantages by means of replication. Franchise chains come immediately to mind (the “McDonalds Approach”) but also firms like The Body Shop. In the Winter and Szulanski approach, replication is essentially a two-stage process: In the first stage, the replicator defines a template that approximates the “Arrow Core,” that is, essentially the full and correct specification of the fundamental replicable features of a business model as well as its ideal target applications. Unfortunately, no one can determine in advance the exact contents of the Arrow Core, and knowledge about it must be acquired through experiential learning. Learning about the Arrow Core may lead to one outlet being identified as a concrete “template” for further replication, or the template may be understood more abstractly in terms of a specification of preferred location choices, standard operating procedures, the products that shall be offered, etc., that is, a “formula.” In the second phase, the replicator replicates the template, trying to “copy exactly.” In this phase, the template or formula for replication is “frozen.”

In a recent paper, “Tracking a Moving Arrow Core: Replication-as-Strategy in IKEA,” Anna Jonsson, a Lund University expert on IKEA, and I argue that IKEA has not followed the rigid two-phase replication strategy described (and recommended) in Winter and Szulanski and other contributions to the replication literature, but has adopted and organized an approach that may be characterized as an ambidextrous one: Exploration and exploitation in IKEA are more like simultaneously ongoing processes than sequential ones. We also describe the organizational mechanisms that IKEA has implemented to steer this process, such as internal units that are responsible for intra-firm knowledge sharing, and we discuss how it is supported by organizational principles, such as corporate values that stress the importance of employees questioning proven solutions while continuously engaging in knowledge sharing. In other words, IKEA organization is geared towards the tracking of a constantly changing Arrow Core. Drop me a mail at njf.smg@cbs.dk if you want a copy of the paper.

Terence Hutchison Special Issue

| Nicolai Foss |

It is a sad fact that I spent a considerable part of my early 20s browsing the pages of the major economics journals of the interwar period. I was particularly interested in what was then called the “monetary theory of the trade cycle” and the role of expectations in the business cycle (Myrdal, Lindahl, Hawtrey, Robertson — and of course Hayek and his many followers and conversants, such as Lachman, Kaldor, and various UK Labour Party economists who until the advent of Keynes’ GT were surprisingly bent on Hayekian business cycle theory. (Here is one of the results of that work). My forays led to the “discovery” of Terence Hutchison’s 1937 paper, “Expectation and Rational Conduct,” in Zeitschrift für Nationalökonomie, a paper that, while over the top in a number of ways, is also an early anticipation of rational expectations and the problems of RE.

Hutchison (1912-2007) is nowadays best known as an economic methodologist, perhaps the first explicit proponent of logical positivism and later Popper’s falsificationism. His 1938 book, The Significance and Basic Postulates of Economic Theory, is often taken as a response to Lionel Robbins’ strongly Austrian-influenced Essay on the Nature and Significance of Economic Science(1932/1935). Hutchison later engaged in a debate with Fritz Machlup, and Hayek buffs will know that Hutchison coined the notion of “Hayek I” and “Hayek II” (based on Hayek’s acceptance of Misesian praxeology).

The latest issue of the always-interesting Journal of Economic Methodology features a special issue symposium on Hutchison. Among the highlights is the publication of a hitherto unpublished, semi-autobiographical essay by Hutchison, and the reproduction by Bruce Caldwell of some revealing letters by Hayek and Hutchison (Hayek did not agree with Hutchison’s interpretation of his changes in the 1930s).

Recent Comments