Posts filed under ‘Innovation’

The Wrong Way to Measure Returns to Public Science Funding

| Peter Klein |

A new Milken Institute report purports to show that “[t]he benefit from every dollar invested by National Institutes of Health (NIH) outweighs the cost by many times. When we consider the economic benefits realized as a result of decrease in mortality and morbidity of all other diseases, the direct and indirect effects (such as increases in work-related productivity) are phenomenal.” There are so many problems with the study I hardly know where to begin. For instance:

1. The authors measure long-term benefit to society as real GDP for the bioscience industries. This is a strange proxy. It is well-known that one of the major impact of public science funding is higher wages for science workers. It is hardly surprising that NIH funding results in higher wages and profits for those in the bioscience industry. Moreover, even if industry activity were the variable of interest, don’t we care about the composition of that activity, not the amount? Which projects were stimulated by NIH funding, and were they the right ones?

2. The results are based on a panel regression of the following equation:

Real GDP for the bioscience industries = f (employment in bioscience industry, labor skill, capital stock, real NIH funding, Industrial R&D in all industries) + state fixed effects + error term.

They interpret the coefficient on NIH funding as the causal effect of NIH funding on bioscience performance. E.g.: “Preliminary results show that the long-term effect of a $1.00 increase in NIH funding will increase the size (output) of the bioscience industry by at least $1.70.” But all the right-hand-side variables are potentially endogenous. For instance, the positive correlation between the dependent variable and NIH funding could reflect winner-picking: the NIH funds projects that are likely to be successful, with or without NIH funding. (The authors briefly mention endogeneity but dismiss it as unimportant.)

This is a version of the basic methodological flaw I attributed to the the political scientists lobbying for NSF money. The issue in question — even assuming the dependent variable is a reasonable measure of social benefit — is what bioscience industry output would have been in the absence of NIH funding. (And, even more important, what would have been the direction of that activity.) Public funding could crowd out private funding, and almost certainly changes the direction of research activity, for good or ill.

3. There are a host of econometric problems, aside from endogeneity — no year fixed effects, no interactions between federal and private funds, the imposition of linear relationships, etc.

If I’m being unfair to the authors, I hope readers will correct me. But this looks to me like another example of special pleading, not careful analysis.

More on Obsolete Technologies

| Peter Klein |

Following up an earlier post on the longevity of obsolete technologies, as specialty markets: Francesco Schiavone has a nice paper, “Vintage Innovation: How to Improve the Service Characteristics and Costumer Effectiveness of Products becoming Obsolete,” reviewing the core theory and discussing the case of the analog turntable (little did I know, not being a club DJ, that you can by a “vinyl emulator” to go wacka-wacka-wacka on your MP3s). Francesco’s Vintage Innovation website has more examples. Check it out!

Vertical (Dis)integration and Technological Change

| Dick Langlois |

One of my longest-running interests has been the relationship between economic change, including technological change, and the boundaries of the firm. In broad strokes, my story is this: when markets are thin and market-supporting institutions weak, technological change, especially systemic change, leads to increased vertical integration, since in such an environment centralized ownership and control may reduce “dynamic” transaction costs; but when markets are thick and market-supporting institutions well developed, technological change leads to vertical disintegration, since in that environment the benefits of specialization and the division of labor outweigh the (now relatively smaller) transaction costs of contracting. This latter scenario is what I called the Vanishing Hand. I recently ran across a new working paper by Ann Bartel, Saul Lach, and Nachum Sicherman, called “Technological Change and the Make-or-Buy Decision,” that supports the Vanishing Hand idea empirically. Here is the abstract.

A central decision faced by firms is whether to make intermediate components internally or to buy them from specialized producers. We argue that firms producing products for which rapid technological change is characteristic will benefit from outsourcing to avoid the risk of not recouping their sunk cost investments when new production technologies appear. This risk is exacerbated when firms produce for low volume internal use, and is mitigated for those firms which sell to larger markets. Hence, products characterized by higher rates of technological change will be more likely to be produced by mass specialized firms to which other firms outsource production. Using a 1990-2002 panel dataset on Spanish firms and an exogenous proxy for technological change, we provide causal evidence that technological change increases the likelihood of outsourcing.

The Spanish dataset is based on questionnaires about outsourcing activities in various mechanical industries. The exogenous proxy is number of patents granted in the U. S. in each industry. So, basically, Spanish firms in industries in which there are a lot of American patents tend to outsource more ceteris paribus than Spanish firms in industries with fewer American patents. Although I always like empirical evidence that supports my own arguments, I also like to play the devil’s advocate. The incomplete-contracts literature (which for me is Coase and Knight as much as Hart and Moore) reminds us that it is harder to write contracts when knowledge is tacit and inchoate. Could it thus be that number of patents is a proxy for the importance of explicit versus tacit knowledge in the industry, and it is the prevalence of the explicit, rather than technological change per se, that makes contracting less costly? My money is still on the Vanishing Hand story.

IT and Higher Ed

| Peter Klein |

Joshua Gans’s Forbes piece on Stanford’s online game theory course brought up a larger point about higher education. I’ve been involved in various online, distance, web-based educational activities for many years. When designing an online course, the typical professor imagines each element of a traditional course, then creates a virtual equivalent. I.e., paper syllabus = html syllabus; books, articles, handouts = pdf files; classroom lecture = webcast lecture; office hours = chat session; pen-and-paper exams = online exams; and so on. The elements are exactly the same as before; only the method of delivery has changed.

Joshua Gans’s Forbes piece on Stanford’s online game theory course brought up a larger point about higher education. I’ve been involved in various online, distance, web-based educational activities for many years. When designing an online course, the typical professor imagines each element of a traditional course, then creates a virtual equivalent. I.e., paper syllabus = html syllabus; books, articles, handouts = pdf files; classroom lecture = webcast lecture; office hours = chat session; pen-and-paper exams = online exams; and so on. The elements are exactly the same as before; only the method of delivery has changed.

This is almost certainly the wrong way to leverage the information technology revolution. The pedagogy is exactly the same. But isn’t this just what we would expect of entrenched incumbents? The record companies didn’t create iTunes. The online New York Times is pretty much like the paper New York Times; it took Google and Flipboard and other innovators to revolutionize the newsreading business.  As we’ve noted before, isomorphism and stasis is exactly what we would expect from a protected cartel — disruptive innovation, in the Christensen sense, will almost certainly come from outside. (Hopefully after Yours Truly is comfortably retired.)

As we’ve noted before, isomorphism and stasis is exactly what we would expect from a protected cartel — disruptive innovation, in the Christensen sense, will almost certainly come from outside. (Hopefully after Yours Truly is comfortably retired.)

Darden Entrepreneurship and Innovation Research Conference

| Peter Klein |

The Darden Entrepreneurship and Innovation Research Conference is now underway in Charlottesville, Virginia. Keynote and roundtable sessions will be streamed on the conference website.

Crowdsourcing in Academia

| Peter Klein |

It’s called “fractional scholarship.”

American universities produce far more Ph.D’s than there are faculty positions for them to fill, say the report’s authors, Samuel Arbesman, senior scholar at the Kauffman Foundation, and Jon Wilkins, founder of the Ronin Institute. Thus, the traditional academic path may not be an option for newly minted Ph.D.s. Other post-graduate scientists may eschew academia for careers in positions that don’t take direct advantage of the skills they acquired in graduate school.

Consequently, “America has a glut of talented, highly educated, underemployed individuals who wish to and are quite capable of effectively pursuing scholarship, but are unable to do so,” said Arbesman. “Ideally, groups of these individuals would come together to identify, define and tackle the questions that offer the greatest potential for important scientific results and economic growth.”

Given the level of relationship-specific investment many research projects require, this isn’t likely to work without some kinds of long-term commitments. But the model may be effective for other projects. And it beats the alternative.

No Best Practice for Best Practice

| Lasse Lien |

An important selling point for the consulting industry is that consultants can presumably help a firm identify and implement “best practice.” Surely the consulting industry is an important channel for disseminating knowledge of better ways of doing things, but identifying what constitutes best practice for a given firm in a given situation is no trivial task, and even if the best practice could be identified, transferring it will be a significant challenge.

This begs the question of whether there is a best practice for identification and transfer of best practices, and whether the consulting industry has identified and adopted such a practice. According to this paper Benjamin Wellstein and Alfred Kieser, the consulting industry in Germany is nowhere near a best practice for best practice. This goes for for both inter- and intra-industry transfer. I’ll bet my hat that this finding holds everywhere.

Well, I guess as long as the consulting industry keeps finding better practices for transferring better practices, we shouldn’t be too disappointed that there is no best practice for best practice. (HT: E.S. Knudsen)

Lazear and Spletzer on Creative Destruction

| Peter Klein |

What labor economists call “churn” is an important part of creative destruction, the combining and recombining of productive resources as business entities appear and disappear. New paper:

Hiring, Churn and the Business Cycle

Edward P. Lazear, James R. Spletzer

NBER Working Paper No. 17910

Issued in March 2012Churn, defined as replacing departing workers with new ones as workers move to more productive uses, is an important feature of labor dynamics. The majority of hiring and separation reflects churn rather than hiring for expansion or separation for contraction. Using the JOLTS data, we show that churn decreased significantly during the most recent recession with almost four-fifths of the decline in hiring reflecting decreases in churn. Reductions in churn have costs because they reflect a reduction in labor movement to higher valued uses. We estimate the cost of reduced churn to be $208 billion. On an annual basis, this amounts to about .4% of GDP for a period of 3 1/2 years.

Computers in Higher Education, 1960s Edition

| Peter Klein |

An illuminating passage from James Ridgeway’s 1968 book The Closed Corporation: American Universities in Crisis, a scathing critique of the university-military-industrial complex. Note the cameo by Jim March:

[University of California officials Ralph W.] Gerard and [R. Dan] Tschirgi are computer fetishists who insist information is knowledge, and that the function of a university is to provide information.

In 1963 and 1964 Chancellor David G. Aldrich, Jr., at Irvine, and Gerard got IBM interested in setting up programs there. The company agreed to install a 1400 system and to supply staff and engineers. An IBM employee, Dr. J. A. Kearns, came along to head the project and was given a part-time appointment at the Graduate School of Administration. The idea was to see whether the computer could be used as a library, for various administrative functions and for teaching.

Gerard paints a glowing picture. He says that one half of the students on the Irvine campus spend at least one hour a week on the computer, and that computers are used in teaching biology, mathematics, economics, sociology and psychology.

After speaking with Gerard, I went along to see the computer in action, and ran into a senior staff man who told me in a jaundiced manner that it wasn’t operating because they couldn’t make the new IBM 360 system work right. This gentleman was exceedingly glum about the possibilities of very many students learning much of anything on the Irvine computers. So was the dean of Social Sciences, James G. March. When I asked him about the use of the machine to teach sociology, he replied grimly that all the computer did was to print out some basic definitions in an introductory course, which, as he pointed out, one could get just as well from reading a book. He went on to say that a minute portion of any introductory course was on a computer, that students spent little time on them, and that most of the time was taken up programming them. March said the difficulty was to devise a system which could answer questions rather than ask them. The most one could really expect was to have a machine pose a problem to the student, who could then go ahead an answer it on his own.

The tech described here is dated but the book itself still packs a punch. In the late 1906s concerns about the close relationships between the federal government (particularly the Pentagon), public research universities, and industry (particularly defense contractors) were new. Now we take for granted that a primary task of the research university is to produce “applied” research in close cooperation with government and industry sponsors, to commercialize its scientific discoveries, to train students for industry, and so on. But this is a fairly recent — mid-20th century — development, and not an obviously desirable one.

Against Brainstorming

| Peter Klein |

Brainstorming appears in many strategy, entrepreneurship, and leadership texts, often mentioned in passing with the implication that it’s a great tool for group decision-making. But the research literature suggests a more circumspect attitude. Indeed, this week’s New Yorker features an interesting and informative essay on some of the latest results:

Brainstorming appears in many strategy, entrepreneurship, and leadership texts, often mentioned in passing with the implication that it’s a great tool for group decision-making. But the research literature suggests a more circumspect attitude. Indeed, this week’s New Yorker features an interesting and informative essay on some of the latest results:

The underlying assumption of brainstorming is that if people are scared of saying the wrong thing, they’ll end up saying nothing at all. The appeal of this idea is obvious: it’s always nice to be saturated in positive feedback. Typically, participants leave a brainstorming session proud of their contribution. The whiteboard has been filled with free associations. Brainstorming seems like an ideal technique, a feel-good way to boost productivity. But there is a problem with brainstorming. It doesn’t work.

Writer Jonah Lehrer goes on to quote Keith Sawyer: “Decades of research have consistently shown that brainstorming groups think of far fewer ideas than the same number of people who work alone and later pool their ideas.” Lots more at the source.

Charles Dickens, Capitalist

| Peter Klein |

Did you know 2012 is the centenary of Charles Dickens’s birth? Dickens is often lumped with Carlyle, Shaw, Ruskin, etc. as a Romantic, Victorian, literary anti-capitalist. (Carlyle indeed disliked capitalism, but not for the usual reasons.) But Dickens, as I originally learned from Paul Cantor, was a wildly successful capitalist and entrepreneur, a driving force behind the great nineteenth-century innovation of the serialized, commercial novel. Consider the following from one Dickens scholar:

Stephen Marcus has called Dickens “the first capitalist of literature” in the sense that he worked within apparently adverse conditions to take advantage of new technologies and markets, creating, in effect, an entirely new role for fiction. In Charles Dickens and His Publishers, Robert Patten quotes Oscar Dystel (president and chief executive of Bantam Paperbacks) on the three “key factors” in his development of a successful paperback line: availability of new material, introduction of the rubber plate rotary press, and development of magazine wholesalers as a distribution arm. As Patten points out, parallel factors operated in the Victorian era: a plethora of writers, new technologies, and expanded distribution. And as methods of papermaking, printing, and platemaking increased in efficiency, so did means of transportation. By 1836, a crucial network of wholesale book outlets in the Strand, peddlers, provincial shops, and the royal mailmade possible by the development of paved roads, fast coaches, and eventually the national railway systemhad been consolidated. The final task facing early publishers was, then, to develop the newly accessible market for their commodity. By lowering prices, emphasizing illustrations and sensational elements, and increasing variety of both form and content, publishers created readers within the largest demographic groups: the rising middle and working classes, where readers had essentially not existed before. . . . (more…)

CFP: DRUID 2012

| Peter Klein |

This year’s DRUID conference, “Innovation and Competitiveness: Dynamics of Organizations, Industries, Systems and Regions,” is 19-21 June 2012 in Copenhagen. See the call for papers below the fold. Submission deadline is 29 February. (more…)

A Formal Model of Experimentation in Firms

| Peter Klein |

Following Knight, Mises, and Lachmann, we have often characterized entrepreneurship on this blog (and the McQuinn blog, which should be on your reading list) as experimentation with combinations of heterogeneous capital resources. Experimentation itself is relatively understudied in the entrepreneurship and strategy literature — we have general theories about the nature and effects of experimentation, indirect empirical evidence on competition as experimentation (e.g., my relatedness stuff with Lasse), case-study evidence about experimentation and innovation within firms, but don’t fully understand the exact mechanisms.

Here’s a new paper that will not be to everyone’s taste, but tries to get at these issues in a formal model of interaction between experimenting firms:

The Role of Information in Competitive Experimentation

Ufuk Akcigit, Qingmin Liu

NBER Working Paper No. 17602, November 2011Technological progress is typically a result of trial-and-error research by competing firms. While some research paths lead to the innovation sought, others result in dead ends. Because firms benefit from their competitors working in the wrong direction, they do not reveal their dead-end findings. Time and resources are wasted on projects that other firms have already found to be dead ends. Consequently, technological progress is slowed down, and the society benefits from innovations with delay, if ever. To study this prevalent problem, we build a tractable two-arm bandit model with two competing firms. The risky arm could potentially lead to a dead end and the safe arm introduces further competition to make firms keep their dead-end findings private. We characterize the equilibrium in this decentralized environment and show that the equilibrium necessarily entails significant efficiency losses due to wasteful dead-end replication and a flight to safety — an early abandonment of the risky project. Finally, we design a dynamic mechanism where firms are incentivized to disclose their actions and share their private information in a timely manner. This mechanism restores efficiency and suggests a direction for welfare improvement.

Strategic Entrepreneurship Conference Starts Today!

| Peter Klein |

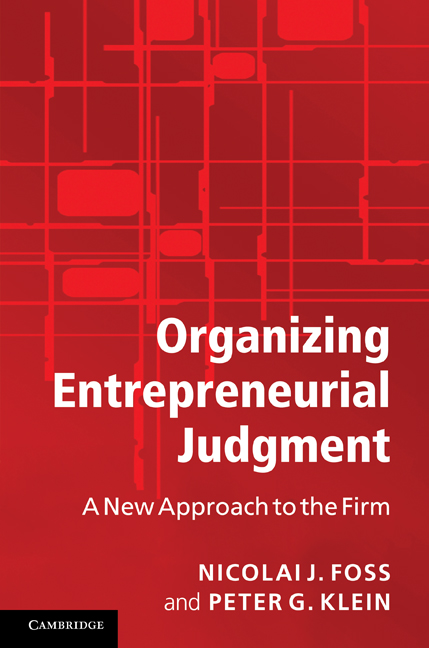

The SMG-McQuinn conference, “Multi- and Micro-Level Issues in Strategic Entrepreneurship,” starts today. Not sure if live-blogging will be feasible (“Nicolai Foss has stepped to the podium. Blue tie, white shirt. Scans the crowd….”) but we’ll post information when we can. The program is here. Some reflections on last year’s conference are here. Naturally Nicolai and I will be in book-promotion mode, hopefully not obnoxiously so.

The SMG-McQuinn conference, “Multi- and Micro-Level Issues in Strategic Entrepreneurship,” starts today. Not sure if live-blogging will be feasible (“Nicolai Foss has stepped to the podium. Blue tie, white shirt. Scans the crowd….”) but we’ll post information when we can. The program is here. Some reflections on last year’s conference are here. Naturally Nicolai and I will be in book-promotion mode, hopefully not obnoxiously so.

Update: Per Bylund is doing some live blogging at the McQuinn blog.

Now Ready for Pre-Order!

| Peter Klein |

This is a placeholder page without much detail, but you can pre-order today! The best news is the price: just £55.00 for the hardback and a mere £19.99 for the paperback — less than a family outing to the cinema, and far more rewarding!

Dissing Apple, Loving Steve

Like so many others, I was deeply saddened to learn today about the passing of Steve Jobs. Jobs was a great entrepreneur, a visionary, a social benefactor. Business leaders like Steve Jobs do more good for humanity than most of the do-gooders put together.

In memory of Steve, Apple fans are sharing their memories of Apple products, listing how many Macs they’ve owned, reminiscing about their first Apple II the way they talk about their first kiss. I’m not one of those. Indeed, I don’t much care for Apple products. I used an Apple II as a teenager, and currently own an iPad, the only Apple product I’ve ever bought. Steve Jobs made a particular kind of device — beautiful, specialized, simple to operate, but expensive, impossible to customize, frustrating to use if you want to use it in a different way than Steve intended. That’s fine — à chacun son goût. Isn’t that the beauty of capitalism? Markets aren’t winner-take all. Neither Steve Jobs nor Bill Gates nor Linus Torvalds nor anyone else decided what products we all should use and made us use them. We didn’t vote for our favorite computer or music player or phone, then all get the one that 51% of the voters preferred. No, we can all have the goods and services we like.

I don’t like Apple products, but I love the fact that other people like them, and that people like Steve Jobs provided them. R.I.P.

Addendum: Steve Horwitz makes the same point.

Schumptoberfest

| Peter Klein |

Kudos to former guest blogger David Gerard for helping organize and host the conference with the über-cool name, Schumptoberfest, 21-23 October at Lawrence University in Appleton, Wisconsin. David Hounshell is giving the keynote address, and the rest looks good too.

Digitopoly

| Peter Klein |

A new group blog by Erik Brynjolfsson, Joshua Gans, and Shane Greenstein. Should be interesting and informative. The authors

noticed that there were many blogs devoted to digital developments and consumer products but the selection focussing on economic and business aspects of the digital world was very limited. Digitopoly’s mission is to provide an economic and strategic management perspective on digital opportunities, trends, limits, trade-offs and platforms; expanding commentary in this important space.

The blog’s name — Digitopoly — reflects our broad interests in the impact of digital technology on competition. While, in some cases, our concern is the preservation of competition in the face of pressures toward monopoly, in others we see opportunities for greater competition and welfare benefits.

Our logo is deliberately iconic. The heavy set line in the graph could represent Moore’s Law (for processing power as time progresses) or Metcalfe’s Law (for the value of networks as more join). It overtakes the simple linear trend represented by thin, broken line. This reflects the idea that linear ways of thinking rarely serve us well in the digital economy.

EGOS 2012, “Self-reinforcing Processes in Organizations, Networks and Professions”

| Peter Klein |

The European Group of Organizational Studies (EGOS) is having the 2012 annual conference in Helsinki, July 2-7. The overall theme is design, and one of the subthemes is “Self-reinforcing Processes in Organizations, Networks and Professions,” a subject sure to interest many O&Mers. See the links above for details. Blurb after the fold: (more…)

Recent Comments