Posts filed under ‘Management Theory’

Two New Papers …

| Nicolai Foss |

… by Yours Truly. The Academy of Management Review just published my paper with Siegwart Lindenberg, “Managing Joint Production Motivation: The Role of Goal Framing and Governance Mechanisms,” and Organization Science just published “Linking Customer Interaction and Innovation: The Mediating Role of New Organizational Practices,” by me, Keld Laursen and Torben Pedersen. Here are the abstracts: (more…)

Is the Internet “Transforming” Business?

| Peter Klein |

In the 1990s and early 2000s there was a huge debate about the impact of information technology on productivity. Robert Solow famously quipped, “You can see the computer age everywhere but in the productivity statistics.” Robert Gordon, Erik Brynjolfsson, Jack Triplett, and many others participated in this debate, with issues revolving around productivity measurement, workplace incentives, organizational complementarities, and more. (I did some work on this too.) The end result was a rough consensus that IT did increase productivity, but that the effects were modest.

The buzz over “wikified” organizations — open-source communities, highly disaggregated firms, crowdsourced production, and the like — gives me a strong sense of déjà vu. Indeed, we have not been kind to the wikinomics view in these pages. Now Don Tapscott, a leader of this movement, seems to be having second thoughts:

In our 2006 book Wikinomics, Anthony D. Williams and I looked at dozens of companies that have used the Internet to transform their business models and achieve tremendous success.

However, in the five years since the book’s publication, we’ve noticed something striking: the rate of business model innovation has not accelerated. Yes, some individual companies have achieved competitive advantage by exploiting the web and networked business models. But overall the gains have been modest.

The reason, says Tapscott, is that “it’s becoming difficult or even impossible for companies to achieve breakthrough success without changing their entire industry’s modus operandi.” This reminds me of the conclusion from the earlier literature that IT has the biggest effect when combined with complementary organizational practices (e.g., Milgrom and Roberts, 1995), which suggests that change doesn’t occur until all elements of the complementary bundle are in place — maybe a long time after the initial innovation.

AoM PDW on Austrian Economics

| Peter Klein |

Four years ago I helped organize an Academy of Management pre-conference workshop on Austrian economics featuring Nicolai, me, Joe Mahoney, Yasemin Kor, Dick Langlois, and Elaine Mosakowski. It was well attended and very well received and we are doing something similar this year. Henrik Berglund, Todd Chiles, Steffen Korsgaard, and I have put together a Professional Development Workshop (PDW) on “Austrian Economics and Entrepreneurship Research.” Full details below. The conference home page is here. Hope to see many O&Mers at the workshop!

Four years ago I helped organize an Academy of Management pre-conference workshop on Austrian economics featuring Nicolai, me, Joe Mahoney, Yasemin Kor, Dick Langlois, and Elaine Mosakowski. It was well attended and very well received and we are doing something similar this year. Henrik Berglund, Todd Chiles, Steffen Korsgaard, and I have put together a Professional Development Workshop (PDW) on “Austrian Economics and Entrepreneurship Research.” Full details below. The conference home page is here. Hope to see many O&Mers at the workshop!

Austrian Economics and Entrepreneurship Research

Please join us Saturday, August 13, from 12:30 to 2:30pm in the San Antonio Convention Center, Room 212A, for a PDW on the Austrian school of economics and its implications for entrepreneurship studies (Program Session #281).

The Austrian school is increasingly well-known in the entrepreneurship field and is typically associated with Joseph Schumpeter’s idea of “creative destruction” and Israel Kirzner’s concept of “entrepreneurial alertness.” But Austrian economics features a number of additional themes, constructs, and emphases — resource heterogeneity, subjectivity of beliefs and expectations, processes of organizational emergence under complexity, and more — that are particularly relevant to research in entrepreneurship, organization, and strategy. Austrian economics is also receiving increasing attention in the broader economics and policy communities, as witnessed by the revival of interest in Austrian business cycle theory as an explanation for the financial crisis and subsequent economic downturn.

This PDW features a panel discussion and interactive table discussions designed to explore Austrian themes in greater detail and examine their applications to research in entrepreneurship and related areas of management studies. The organizers also hope to encourage and help develop the growing community of management scholars interested in the Austrian school.

The program begins with an introduction and overview by session organizers Henrik Berglund (Chalmers University of Technology), Todd Chiles (University of Missouri), Peter Klein (University of Missouri), and Steffen Korsgaard (Aarhus University), followed by breakout sessions organized around particular themes such as alertness and opportunity discovery, heterogeneity of the entrepreneurial imagination, resource heterogeneity and Austrian capital theory, entrepreneurship and equilibration, entrepreneurship and punctuated disequilibrium. Other distinctively Austrian (e.g., opportunities and action, the role of individuals, the individual-opportunity nexus, the market process, methodological individualism) and related (e.g., effectuation and bricolage) ideas will also figure prominently in the discussions.

The groups will then reassemble to share findings and results with the larger group. Ample time will be allowed for informal discussion and networking.

Please contact Henrik Berglund (henrik.berglund@chalmers.se) with any questions.

Decentralization and the Walmart Decision

| Peter Klein |

On Monday the US Supreme Court turned refused to hear the class-action discrimination suit against Walmart (technically, the Court denied to certify the plaintiffs as a single class for purposes of a class-action suit). I haven’t followed the case closely enough to have an opinion on the merits (or the role of sociologists). But a main legal issue in the case — whether Walmart’s policy of delegating hiring and promotion decisions to local managers makes the firm itself liable for illegal personnel behavior — raises important questions for organization theory.

According to the decision (no, I didn’t try to read all 42 pages):

Pay and promotion decisions at Wal-Mart are generally committed to local managers’ broad discretion, which is exercised “in a largely subjective manner.” . . . Local store managers may increase the wages of hourly employees (within limits) with only limited corporate oversight. As for salaried employees, such as store managers and their deputies, higher corporate authorities have discretion to set their pay within preestablished ranges.

Promotions work in a similar fashion. Wal-Mart permits store managers to apply their own subjective criteria when selecting candidates as “support managers,” which is the first step on the path to management. Admission to Wal-Mart’s management training program, however, does require that a candidate meet certain objective criteria,including an above-average performance rating, at least one year’s tenure in the applicant’s current position, and a willingness to relocate. But except for those requirements, regional and district managers have discretion to use their own judgment when selecting candidates for management training. Promotion to higher office — e.g., assistant manager, co-manager, or store manager — is similarly at the discretion of the employee’s superiors after prescribed objective factors are satisfied. (more…)

Do Senior Managers Make Better Decisions Than Students?

| Nicolai Foss |

Even management students may occasionally suffer from confidence and self-esteem problems. I have had many students confide that they were more than a little scared at the prospect of landing a real job where their decision-making skills would be compared to older, wiser, smarter, etc. colleagues. Rather than directing them to this site, in the future I am going to give such students a copy of Gary E. Bolton, Axel Ockenfels and Ulrich Thonemann’s “Who Is the Best at Making Decisions? Managers or Students?” They set up a simple experiment based on a simple profit maximizing problem, and find that practitioner performance isn’t as good as graduate business students’. Moreover, the learning curve of the latter is steeper than that of practicioners. (more…)

HRM in Film

| Peter Klein |

It isn’t every day you can blog about a film called The Human Resources Manager so, well, here it is:

A touching black comedy with a heart of gold, The Human Resources Manager is the story of a jaded and grumpy HR Manager stuck with the duty of delivering the corpse of a former employee to her estranged Eastern European family for burial. . . .

The film is part road trip journey, but it’s mostly a character study of the unnamed worker bee who works as the HR Manager at a large bakery in Israel. When an employee turns up dead in a car bomb explosion, the media links the worker to the bakery. After a defamatory article against the treatment of the deceased employee breaks, the company assigns our reluctant hero, the HR Manager, to band-aid the situation. This means setting the record straight with the press, a particularly suspect tabloid reporter, and making his company look thoughtful and decent. Soon the man finds himself lugging the corpse and coffin around town looking for a next of kin to relieve him of his duty.

I’m putting it on my Netflix list, and considering it for classroom use!

Miscellaneous Links

| Peter Klein |

- A public service from our good-twin site: What makes a good review?

- History matters? “[T]he descendants of societies that traditionally practiced plough agriculture, today have lower rates of female participation in the workplace, in politics, and in entrepreneurial activities, as well as a greater prevalence of attitudes favoring gender inequality.”

- Another review of The Invention of Enterprise, by frequent O&M commenter Michael Marotta.

- Regression to the mean? A McKinsey report (via Russ) illustrates the difficulty of long-run supra-normal growth: “a startling 44 percent of all companies that grew at rates faster than 15 percent from 1994 to 1997 were growing at rates lower than 5 percent ten years later.”

- Another attempt to model the evolution of cooperation — this time by Acemoglu and Jackson.

Henry Manne on Entrepreneurship

| Peter Klein |

Important new paper by Henry Manne on entrepreneurship (Quarterly Journal of Austrian Economics, Spring 2011). It won’t surprise you to know that Henry has a solution to the problem of encouraging entrepreneurial behavior among corporate managers: allow them to trade on inside information.

Entrepreneurship, Compensation, and the Corporation

Henry G. ManneThis paper revisits the concept of entrepreneurship, which is frequently neglected in mainstream economics, and discusses the importance of defining and isolating this concept in the context of large, publicly held companies. Compensating for entrepreneurial services in such companies, ex ante or ex post, is problematic — almost by definition — despite the availability of devices such as stock and stock options. It is argued that insider trading can serve as a unique compensation device and encourage a culture of innovation.

Competitive Advantage, Network Advantage, and Vienna

| Peter Klein |

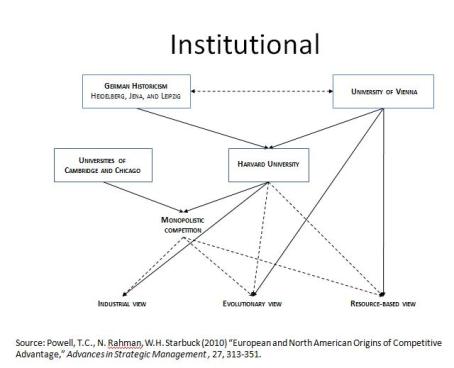

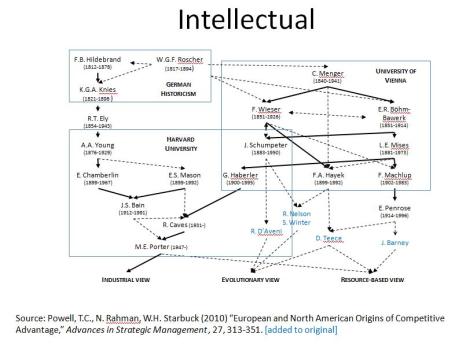

At last week’s ACAC Joel Baum gave a very interesting presentation (ppt) on the institutional and intellectual histories of two important strands in management thought, the literature on competitive advantage and the literature on network advantage. These two strands developed largely in isolation but, as it turns out, can both trace important parts of their development to the University of Vienna and the Austrian school of economics. Check out the genealogies below, captured from Joel’s slides. First, two diagrams on the origins of the competitive advantage approach (click to enlarge):

Now, two on the origins of network advantage theory: (more…)

ACAC 2011

| Peter Klein |

The Atlanta Competitive Advantage Conference, otherwise known as ACAC, starts tomorrow. I’m there, along with former O&M guest bloggers Joe Mahoney, Steve Postrel, and Russ Coff, and a whole bunch of interesting and important people in strategy, organization theory, entrepreneurship, innovation, HRM, and more. Check out the program, as well as the main site with information about past and future events. Besides the workshops and paper sessions there are special events like a symposium with Jay Barney on the RBV after 20 years and keynotes from Rebecca Henderson and Joel Baum. The only thing ACAC needs is a spokesperson — I think Gilbert Gottfried might be available.

The Organizational Structure of Al Qaeda

| Peter Klein |

Speaking of organizational structure, here’s former O&M guest blogger Craig Pirrong on Al Qaeda:

There is a concerted effort underway to portray Bin Laden as exerting operational control over Al Qaeda, based on material collected during the raid on his compound. Color me skeptical.

First, it’s hard to imagine how he could exercise any control at anything but the broadest strategic and conceptual level while he was relying on couriers to communicate with subordinates. Second, this hierarchical model is contrary to virtually all that has been written about Al Qaeda going back to its early days: the organization has been consistently portrayed as networked and distributed rather than hierarchical. Indeed, the conventional characterization of Al Qaeda represents it as more of a franchise operation in which the franchisees have considerable autonomy.

But let’s assume for a moment that the organization was hierarchical, and that operational elements required direction and approval from Bin Laden to implement any attack. If that’s true, we may have actually done ourselves a disservice by killing Osama. For it would be almost trivially simple to get inside AQ’s OODA (“observe, orient, decide, and act”) loop and disrupt and destroy its operations. Even if we didn’t know what AQ was up to, we could disrupt their plans just by mixing (randomizing) our strategies, by unexpectedly changing up the way we do things. If response to such changes required the locals carrying out missions to report back to OBL via a painfully slow communications system, await a decision, and wait for the decision to be couriered back, they would be unable to do anything serious. In this case, killing OBL would free the locals to be more flexible and responsive — and hence more dangerous. It would permit AQ to become more of a network, less predictable, and more able to adapt to our moves.

I too doubt this emerging meme on OBL as operational figure, perhaps for somewhat different reasons: I assume that any official information about the operation and its significance is primarily propaganda, not transparent disclosure. Naturally the Administration would want to exaggerate the significance of Bin Laden’s, um, “retirement.”

Knightian Uncertainty

| Peter Klein |

| Peter Klein |

A nice post from good-twin Brayden. He quotes Chuck Perrow:

In what should be considered a classic case of the failure to take a possibilistic approach, consider this statement by Tsuneo Futami, a nuclear engineer who was the director of Fukushima Daiichi in the late 1990s: “We can only work on precedent, and there was no precedent. When I headed the plant, the thought of a tsunami never crossed my mind.”

Futami was not alone in his thinking. Experts throughout the nuclear industry and government regulatory agencies not only failed to predict the likelihood of a giant earthquake and tsunami, but also failed to examine the vulnerabilities of Fukushima Daiichi’s design to a natural disaster of this scale. Instead, they relied on a history of successful operation as an assurance of future safety. As a result, they ignored or underestimated a number of major risks that have since doomed the plant.

In other words, decision makers do not enumerate possible outcomes, assign probabilities to each, compute expected values, and act accordingly, a la Luce and Raiffa (1957). Instead, they use heuristics, follow precedent, update priors, and so on. In Knightian terms, they use judgment.

My forthcoming book with Nicolai explores these aspects of Knightian judgment in much greater detail. Look for some excerpts to follow.

Humanoid Resource Management

| Peter Klein |

I can’t quite tell if this “Schumpeter” column, urging management scholars to think more carefully about “homo-robo relations,” is meant to be taken seriously. It gave me a few chuckles, anyway.

Until now executives have largely ignored robots, regarding them as an engineering rather than a management problem. This cannot go on: robots are becoming too powerful and ubiquitous. Companies may need to rethink their strategies as they gain access to these new sorts of workers. Do they really need to outsource production to China, for example, when they have clever machines that work ceaselessly without pay? They certainly need to rethink their human-resources policies — starting by questioning whether they should have departments devoted to purely human resources.

And what about robo-agency theory? Can robots be programmed to be intrinsically motivated — finally rendering certain management theories intelligible — or do they respond to incentives in a predictable way? Are they risk averse? Will they behave opportunistically? Can they be “nudged” by clever behavioral economists?

Actually the article does make some serious points, e.g., economists and management scholars should prepare for an onslaught of neo-Luddite, anti-automation, protectionist gibberish about robots “taking away our jobs.” (Maybe if they’re domestically made robots it will be OK?)

Why Do Firms Hire Management Consultants?

| Peter Klein |

Academic economists and management scholars are often skeptical of management consulting firms. Their advice seems fluffy, ad hoc, unscientific. But consulting firms continue to prosper. Are their clients irrational?

Academic economists and management scholars are often skeptical of management consulting firms. Their advice seems fluffy, ad hoc, unscientific. But consulting firms continue to prosper. Are their clients irrational?

I always assumed signaling plays a role. One can imagine a Spence-style separating equilibrium in which high-quality firms signal their unobservable characteristics to customers, suppliers, rivals, etc. by hiring an expensive consulting firm, while low-quality firms find this prohibitively costly. Of course, all consulting firms are not alike, and there are many different types of consulting services (e.g., strategy — more fluffy; IT implementation — less fluffy).

An article in the new JMS by Donald Bergh and Patrick Gibbons looks at the signaling value of consulting, measuring the stock-market reactions to firms’ announcements of hiring a consulting firm. Excess returns are positive and significant, and increasing in the client’s prior performance — the market likes it when “good” firms hire consultants. (The effects don’t seem to depend on the reputation of the consulting firm, though.) This is consistent with my story above, though we’d need to know something about firms that could have hired a consultant but didn’t to say more.

Information versus Knowledge

| Peter Klein |

[T]here’s enough information coming at us from all sides to leave us feeling overwhelmed, just as people in earlier ages felt smothered by what Leibniz called “that horrible mass of books that keeps on growing.” In response, 17th-century writers compiled indexes, bibliographies, compendiums and encyclopedias to winnow out the chaff. Contemplating the problem of turning information into useful knowledge, Gleick sees a similar role for blogs and aggregators, syntheses like Wikipedia, and the “vast, collaborative filter” of our connectivity. Now, as at any moment of technological disruption, he writes, “the old ways of organizing knowledge no longer work.”

But knowledge isn’t simply information that has been vetted and made comprehensible. “Medical information,” for example, evokes the flood of hits that appear when you do a Google search for “back pain” or “vitamin D.” “Medical knowledge,” on the other hand, evokes the fabric of institutions and communities that are responsible for creating, curating and diffusing what is known. In fact, you could argue that the most important role of search engines is to locate the online outcroppings of “the old ways of organizing knowledge” that we still depend on, like the N.I.H., the S.E.C., the O.E.D., the BBC, the N.Y.P.L. and ESPN.

That’s Geoffrey Nunberg reviewing James Gleick’s new book, The Information (Random House, 2011). Gleick burst onto the scene with 1987’s Chaos: The Making of New Science, which introduced the butterfly effect, Mandelbrot sets, fractal geometry, and the like into popular culture. (Don’t blame Gleick for the silly Ian Malcolm character in Jurassic Park, or the even sillier Ashton Kutcher movie.) I haven’t gotten my hands on a copy of The Information (gotta love the definite article, as in “the calculus”) but, as best as I can tell from the Google books version, Gleick doesn’t get into the Hayekian-Polanyian distinctions between parameterizable “information” and tacit knowledge that particularly interest O&M readers. (Another good quote from the review: “[T]here’s no road back from bits to meaning. For one thing, the units don’t correspond: the text of ‘War and Peace’ takes up less disk space than a Madonna music video.”) Still, the book should be worth a read.

Management Textbooks Bungle Weber

| Peter Klein |

Most management scholars, like most economists, have little interest in doctrinal history, so it’s not surprising they don’t pay much attention to the history of management thought. But Stephen Cummings and Todd Bridgman’s “The Relevant Past: Why the History of Management Should Be Critical for Our Future” (Academy of Management Learning and Education, March 2011) is an eye-opener. Focusing on Max Weber, Cummings and Bridgman document a series of whoppers that appear consistently in leading management texts, such as the belief that “ideal type” means best or optimal; that Weber did his major work in the 1940s (Parsons’s translation of Wirtschaft and Gesellschaft appeared in 1947, 27 years after Weber’s death); that Weber personally admired bureaucracy (In Search of Excellence avers that Weber “pooh-poohed charismatic leadership and doted on bureaucracy”); and other gross misunderstandings. FAIL.

Oxford Handbook of Human Capital

| Peter Klein |

I just received a copy of the Oxford Handbook of Human Capital, edited by Alan Burton-Jones and J.-C. Spender, and it looks terrific. The concept of “human capital” came from developments in macroeconomics and labor economics (and, it is often forgotten, entrepreneurship) but is increasingly influential in organization and strategy research. (Witness, for example, the new SMS Strategic Human Capital Interest Group.) These Handbook chapters “reveal the importance of human capital for contemporary organizations, exploring its conceptual underpinnings, relevance to theories of the firm, implications for organizational effectiveness, interdependencies with other resources, and role in the future economy,” says the cover blurb. O&M readers may especially like the section on “Human Capital and the Firm,” with chapters on TCE (by Foss), agency theory (Spender), the RBV (Jeroen Kraaijenbrink), entrepreneurship and the theory of the firm (Brian Loasby), and the knowledge-based theory of the firm (Georg von Krogh and Martin Wallin). Check it out!

Mario Rizzo’s Graduate Course in Behavioral Economics

| Peter Klein |

Check out the syllabus and join the discussion at ThinkMarkets. I appreciate boat-rocking as much as anyone but am personally in what Mario terms (in his syllabus) the “classical” camp. Still, this is a course I would definitely take. If he’s an easy grader.

Counterintuitive Research Result of the Day

| Peter Klein |

According to the current issue of Managerial and Decision Economics, women free ride more than men:

An Experimental Test of Behavior under Team Production

Donald Vandegrift and Abdullah YavasThis study reports experiments that examine behavior under team production and a piece rate. In the experiments, participants complete a forecasting task and are rewarded based on the accuracy of their forecasts. In the piece-rate condition, participants are paid based on their own performance, whereas the team-production condition rewards participants based on the average performance of the team. Overall, there is no statistically significant difference in performance between the conditions. However, this result masks important differences in the behavior of men and women across the conditions. Men in the team-production condition increase their performance relative to men in the piece-rate condition. However, this gap in male performances across conditions diminishes over the course of the experiment. In contrast, women in the team-production condition show significantly lower performance than the women in the piece rate. As a consequence of these differences, men in the team-production condition show significantly better performance than women in the team-production condition. We also find evidence that men show stronger performance when they are in teams with a larger variation in skill level.

I’m trying to derive implications for firm performance in light of Alchian and Demsetz (1972). But come on, give me the Go-Gos or Bangles over Backstreet Boys or Jonas Brothers any day.

Recent Comments