Posts filed under ‘Management Theory’

The Performative Effects of Social Constructionist Professors in Business Schools

| Nicolai Foss |

Many European business schools praise disciplinary diversity. Some style themselves as “business universities,” rather than “traditional” business schools. Such schools may have a substantial contingent of faculty from the humanities, including historians, literary theorists, and philosophers, as well as sociologists and political scientists. The probability of such faculty subscribing to social constructionism is high. Typically, this perspective is taught to the students in courses on communication, whether intercultural or not, the theory of science, cross-cultural management, and so on. It is pretty much everywhere.

Those in sociology who stress “reflexivity” and “performativity” tell us that our theorizing, as mediated through teaching, influences the objects of theorizing. What may be the performative effect of social constructionist professors? My hypothesis is that the students they teach will end up acting like Hayek’s “constructivist rationalists” on the level of society, that is, managers who believe everything in organizations is malleable, and may therefore do substantial damage to the organizations they manage. The Wiki on social constructionism provides a neat summary of Ian Hacking’s celebrated critique of social constructionism:

Ian Hacking, having examined a wide range of books and articles with titles of the form “The social construction of X” or “Constructing X”, argues that when something is said to be “socially constructed”, this is shorthand for at least the following two claims:

(0) In the present state of affairs, X is taken for granted; X appears to be inevitable.

(1) X need not have existed, or need not be at all as it is. X, or X as it is at present, is not determined by the nature of things; it is not inevitable.

Hacking adds that the following claims are also often, though not always, implied by the use of the phrase “social construction”:

(2) X is quite bad as it is.

(3) We would be much better off if X were done away with, or at least radically transformed.

If this is foundational for you as a manager, you will likely have little respect for what has evolved inside an organization, because “it is not inevitable.” You will be unimpressed by efficiency arguments from economics and functionalist arguments from sociology that explain the presence of a given feature of an organization. Your urge is to change the organization erratically according to your whims, and nourish ongoing turmoil. Psychological/implicit contracts suffer. Negative implications for productivity and firm-level performance follow.

The Confusing “Business Model” Construct

| Nicolai Foss |

The discourse of both practicing managers and management scholars abounds with concepts and jargon that sound fine, and surely refer to something real and important, but are used in a hopelessly imprecise manner and have all sorts of different, often conflicting, meaning attached to them. Examples of yesteryear include “value creation,” “competitive advantage,” and “value proposition” — “yesteryear”, because reasonable clarity has gradually been achieved with respect to their meaning.

Another example, where lack of clarity unfortunately persists, is that of “business models” — which refers to, for example, “bricks and clicks business models” (which is mainly about integrating online and offline presence), “collective business models” (which is mainly about pooling resources across firms), “cutting out the middleman” (which is, well, you guessed it), “franchising” (which is a particular contractual arrangement for handling distribution), “freemium” (offering free basic services and expensive premium services” etc., etc. (examples are from the wiki on the subject). So, business models are about internet distribution, the contractual form of distribution, resource sharing, cutting out middlemen, differentiation policies, etc. It is not clear what unites all this, except, perhaps, a basic concern with the consumer/customer side of value creation and appropriation (and even that doesn’t hold for all conceptions). Moreover, some argue that building a business model is subordinate to formulating a strategy, while others (e.g., Teece) argue that strategies are on a lower level than business models.

Obviously, attempts to reduce all this confusion are highly laudauble. Two recent such attempts deserve mention here. One is an excellent paper, “The Business Model: Theoretical Roots, Recent Developments, and Future Research,” by Christoph Zott, Raphael Amit, and Lorenzo Massa. Among other things they argue that the business model is a meaningful unit of analysis, and should be understood as a firm-centric, yet boundary-spanning activity system supported by a logic of value creation and appropriation. The second attempt is a special issue of Long Range Planning on the subject, with contributions from such luminaries as David Teece, Raphael Amit, Rita McGrath, Muhammad Yunus, Yves Doz, Michael Tushman and many others. I have only read the Teece paper, but look forward to reading the rest. Teece (in “Business Models, Business Strategy, and Innovation”) begins by arguing the “concept of a business model lacks theoretical grounding in economics or in business studies,” goes on to offer his own definition, supplies several examples, discusses the conceptual differences between business models and business strategies and ends by linking the business model constructs to his earlier work on how the organization of the innovation process influences the appropriation of value from innovation. Like so many articles in LRP, this paper will be excellent for the classroom.

Managing Innovation

| Peter Klein |

My old classmate Hank Chesbrough offers some thoughts on managing innovation in HBR’s Conversation Blog. Previous decades brought us systems analysis, PERT, TQM, supply chain management, and open innovation. What’s next? Hank’s predictions:

First, management innovation will become more collaborative. Opening up the innovation process will not stop with accessing external ideas and sharing internal ideas. Rather, it will evolve into a more iterative, interactive process across the boundaries of companies, as communities of interested participants work together to create new innovations. . . .

Second, business model innovation will become as important as technological innovation. . . . Third, we will need to master the art and science of innovating in services-led economies. Most of what we know about managing innovation comes from the study of products and technologies. Yet the world’s top advanced economies today derive most of their GDP from services rather than products or agriculture.

Finally — a Field Experiment!

| Lasse Lien |

Field experiments represent a killer combination of a causal design and external validity — the best of both the classical (laboratory) experiment and the natural experiment. Unfortunately, field experiments in strategy, management, organizational economics, etc. are often prohibitively costly, morally questionable, or both. But sometimes a field experiment is feasible, and when it is, it tends to stand out as particularly interesting.

This paper illustrates this point quite well, IMHO. The paper is a field experiment on the not entirely trivial question: Does Management Matter?

University Restructuring, Agricultural Economics Edition

| Peter Klein |

The current issue of AAEA Exchange, the newsletter of the Agricultural and Applied Economics Association (formerly American Agricultural Economics Association), features three perspectives on the long-term viability of maintaining separate departments of economics and agricultural economics. (Much of the discussion would apply to business economics departments too.) Ron Mittelhammer of Washington State argues for consolidation, Ken Foster of Purdue for keeping separate departments, and Rob King of Minnesota for the transformation of agricultural economics departments to applied economics departments.

The issues are organizational and strategic and familiar to O&M readers. Mittelhammer emphasizes tangible resources and a shared intellectual heritage and downplays accumulated routines and capabilities, organizational culture, etc.:

Arguably above all other rationale, mergers are also warranted because, fundamentally, economics is economics. Agricultural economics is a field of economics, not some other paradigm of economics, and is no more distinct from its parent discipline than other fields such as labor economics, international economics, health economics. . . .

Too often of late, it appears that the last ditch attempt at justifying the separation of economic units degenerates to the issue of faculty personalities, the correlated issue of seemingly unbridgeable differences in “professional cultures,” and the fear of open faculty warfare that might be ignited by a merger, rather than the existence of truly distinct and defensible differences in the methodologies used to do economic analysis in agricultural and applied, versus the “other” economics disciplines. (more…)

The Future of Managerial Economics

| Peter Klein |

The December 2010 issue of Managerial and Decision Economics features an editorial by Paul Rubin and Tony Dnes on the state of the field, “Managerial Economics: A Forward Looking Assessment.” As they note, the “traditional approach” — basically applied neoclassical microeconomics, production theory in particular — has been augmented by new developments,

particularly in areas such as globalization, the economics of organization, information economics, strategic behavior, the learning organization, risk management, business ethics, and behavioral economics. All of these topics are hot in modern managerial economics and are slowly feeding through into MBA and similar courses.

The modern trends are often referred to as “the new managerial economics.” Some modern texts even use the term explicitly (Boyes, 2008) and focus on questions of “organizational architecture” including areas such as incentive structures in personnel economics. There are increasing numbers of specialist works emerging in these areas, which are coming to feature in influential handbooks (Lazear, 2009). Personnel economics, for example, applies economics to human resources topics, including information interactions, problems of team coordination, morale, and seniority systems. . . . In managerial terms, this field is a natural development of the economics of organization and of labor economics, and we hope to see much future research coming through. (more…)

Google Tries Selective Intervention?

| Peter Klein |

Can a large firm do everything a collection of small firms can do, and more? If not, how do we understand the limits to organization? Arrow focused on the information structure inside firms. I favor Mises’s economic calculation argument. Williamson’s preferred explanation for the limits to the firm is the impossibility of selective intervention — the idea that higher-level managers cannot credibly commit to leave lower-level managers alone, except when such selective intervention would generate joint gains. Williamson’s argument is not, however, universally embraced (or even understood the same way — see the comments to Nicolai’s post).

Google apparently sees things Williamson’s way and has formulated an explicit policy on “autonomous units” designed to address the problem. Such units “have the freedom to run like independent startups with almost no approvals needed from HQ, ” reports TechCrunch. “For these divisions, Google is essentially a holding company that provides back end services like legal, providing office space and organizing travel, but everything else is up to the pseudo-startup.” Can it work? Insiders are doubtful. The TechCrunch reporter even frames Williamson’s thesis in this folksy way:

There’s a lie that companies and entrepreneurs tell themselves in order to commit to an acquisition.

Oh, we’re not going to change anything! We’re just going to give you more resources to do what you’ve been doing even better!

Yeah! They bought us for a reason, why would they ruin things?

It usually works for a little while, but big company bureaucracy– whether it’s HR, politics or just endless meetings– almost always creeps in. It’s a law of nature: Big companies just need certain processes to run and entrepreneurs hate those processes because they stifle nimble innovation.

Megachurches and Management Education

| Peter Klein |

This month’s Fast Company profiles Willow Creek, perhaps the world’s most famous megachurch. The article opens by describing a conversation between Willow Creek pastor Bill Hybels and management guru Peter Drucker:

Hybels decided that one of his unique contributions [to ministry] could be to create a resource for pastors who didn’t have firsthand access to thinkers like Drucker. The need was clear. A 1993 survey of evangelical pastors by seven seminaries found that while they said their education had prepped them well in church history and theology, they felt undertrained in administration, management, and strategic planning. “In the 1950s, a pastor preached on Sundays, did weddings and funerals, and visited the sick,” says Dennis Baril, senior pastor of the Community Covenant Church in Rehoboth, Massachusetts, which hosts a satellite summit site every year. “I have almost 50 ministries that need to be put together, scheduled, organized, and led. It’s a different skill set.”

Church conferences did little to address that need. “Most of them are pastors learning from pastors,” says Jim Mellado, who wrote a 1991 Harvard Business School case study on Willow Creek. “If you only hear preaching from the choir, you’re never stretched. You never see things from another perspective.”

Sounds a bit like university administrators, most of whom learn administration from, well, other university administrators. (Who may have been English professors in a previous life.)

Here’s the HBS case on Willow Creek, and here are Mike Porter’s PowerPoint slides from his 2007 presentation at Willow Creek’s leadership summit. Interesting factoid from the Economist via Wikipedia: in 2007, five of the world’s ten largest Protestant churches were in South Korea.

“Robert S. McNamara and the Evolution of Modern Management”

| Peter Klein |

That’s the title of a new HBR article by Phil Rosenzweig (author of the excellent Halo Effect). I’ve been interested in McNamara and his role in business history since grad school, when I was researching “management by the numbers” and similar techniques that flourished during the conglomerate boom in the 1960s. (See previous O&M posts on McNamara here and here.) Rosenzweig provides a nice summary of some of strengths and weaknesses of McNamara’s dispassionate, “rational,” quantitative approach (see especially the sidebar, “What the Whiz Kids Missed”). Lots of information and ideas related to decision theory, organizational design, multitasking, performance evaluation, innovation, etc. Excerpt:

Whether at Ford or in the military, in business or pursuing humanitarian objectives, McNamara’s guiding logic remained the same: What are the goals? What constraints do we face, whether in manpower or material resources? What’s the most efficient way to allocate resources to achieve our objectives? In filmmaker Errol Morris’s Academy Award–winning documentary The Fog of War, McNamara summarized his approach with two principles: “Maximize efficiency” and “Get the data.”

Yet McNamara’s great strength had a dark side, which was exposed when the American involvement in Vietnam escalated. The single-minded emphasis on rational analysis based on quantifiable data led to grave errors. The problem was, data that were hard to quantify tended to be overlooked, and there was no way to measure intangibles like motivation, hope, resentment, or courage. . . .

Equally serious was a failure to insist that data be impartial. Much of the data about Vietnam were flawed from the start. This was no factory floor of an automobile plant, where inventory was housed under a single roof and could be counted with precision. The Pentagon depended on sources whose information could not be verified and was in fact biased. Many officers in the South Vietnamese army reported what they thought the Americans wanted to hear, and the Americans in turn engaged in wishful thinking, providing analyses that were overly optimistic.

Kiffin Goods

| Peter Klein |

US college football fans may appreciate this paper, written by three University of Tennessee economists:

Kiffin Goods

by Omer Bayar, William Neilson, and Stephen Ogden

February 2, 2010Abstract: In this paper, we investigate the possibility of a managerial input that experiences increasing compensation along with decreasing intensity. We call this type of input a “Kiffin Good” after the head football coach Lane Kiffin. We propose a novel production process that might lead to Kiffin behavior.

The Kiffin Good is described as the supply-side equivalent of the so-called Giffen Good — for the latter, the quantity demanded increases with price, while for the former, price rises as quantity falls. (Note that some of us have politically incorrect views on Mr. Giffen’s famous paradox.)

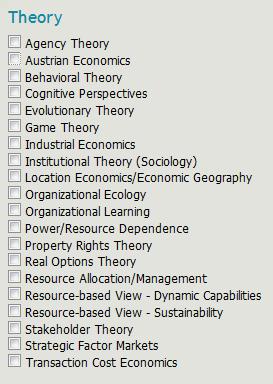

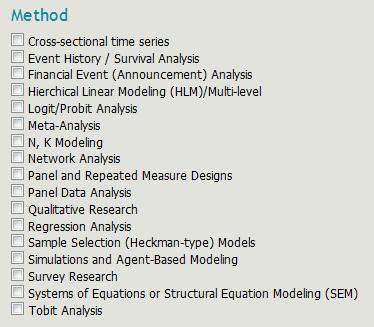

The Diversity of Strategic Management Research

| Peter Klein |

In my graduate class this morning we were discussing the diversity of theories and approaches in strategic management research when a useful illustration came to mind. I recently registered as a reviewer for the upcoming SMS conference and, as requested, indicated my areas of interest and expertise. The lists for “Theory” and “Method,” reproduced below, are instructive. I mean, can you imagine such lengthy lists for the AEA meeting or a conference in accounting or finance? (OK, perhaps still too short for some. . . .)

Entrepreneurial Ability as a Latent Variable

| Peter Klein |

It’s the weekend after Thanksgiving, so naturally I’m thinking about residuals — not leftover turkey and cranberry sauce, but entrepreneurial characteristics and behaviors as residuals, as latent variables that leave traces in outcomes that we can’t otherwise explain. I’ve argued before that common measures of entrepreneurship such as startups, self-employment, patents, venture funding, etc., while related to entrepreneurship, are epiphenomena, manifestations of an underlying, unobservable attribute or behavior such as judgment, alertness, innovation, or adaptation. (These are difficult, if not impossible, to measure directly; asking survey respondents, for instance, “How many opportunities did you identify this month?” is not quite the same thing as measuring Kirznerian alertness!) In a recent musing on strategic entrepreneurship I suggested that

many of the entrepreneurial capabilities we’re really interested in are latent, and best captured as residuals — e.g., something heritable and not explainable by other observables. . . . Mike Wright talked [at the CBS strategic entrepreneurship conference] about mobility, both across firms or projects (habitual entrepreneurs, spin-outs) and across countries (immigrant and returnee entrepreneurs, transnational entrepreneurs). From the perspective of research design, some of these movements may be useful for isolating the “entrepreneurial” essence, such as it is.

Seth Carnahan, Rajshree Agarwal, and Ben Campell have an interesting new paper, “The Effect of Firm Compensation Structures on the Mobility and Entrepreneurship of Extreme Performers,” that takes this kind of approach, measuring entrepreneurial ability as the residual in a wage regression. Most of the variation in wages can be explained by age, experience, race, gender, education, and other observables; what remains is partly measurement error, but can also include a latent ability parameter. Seth, Rajshree, and Ben use this parameter, along with the wage structure of an employee’s existing firm, to explain which employees tend to leave to join new firms, particularly startups. Check it out!

Prahalad Conference

| Peter Klein |

My colleague Karen Schnatterly, along with Bob Hoskisson and M. B. Sarkar, are organizing a special SMS conference to honor the late C. K. Prahalad. It’s 10-12 June 2011 in San Diego. The conference “will bring together scholars, executives, and consultants who have researched or applied CK Prahalad’s ideas. There will also be a number of panel sessions that include individuals such as Gary Hamel, Yves Doz, and Stuart Hart.” Proposals are due 21 January 2011.

My colleague Karen Schnatterly, along with Bob Hoskisson and M. B. Sarkar, are organizing a special SMS conference to honor the late C. K. Prahalad. It’s 10-12 June 2011 in San Diego. The conference “will bring together scholars, executives, and consultants who have researched or applied CK Prahalad’s ideas. There will also be a number of panel sessions that include individuals such as Gary Hamel, Yves Doz, and Stuart Hart.” Proposals are due 21 January 2011.

Interesting New Books

| Peter Klein |

In place of the “What I’ve Been Reading Lately” posts that show up regularly on certain blogs, I hereby offer something slightly less egocentric, the “What I’ve Been Receiving Lately” post. It contains a list of books I’ve recently received by mail, some by choice, others because publishers sent them (perhaps hoping I’d blog about them — Mission Accomplished!). Not the most scientific sample selection process, but there you go.

- Jesús Huerta de Soto, Socialism, Economic Calculation, and Entrepreneurship (Elgar, 2010). English translation of an important work first published in Spanish in 1992.

- Guinevere Liberty Nell, Rediscovering Fire: Basic Economic Lessons from the Soviet Experiment (Algora, 2010). What the failure of central planning teaches about markets and institutions.

- Koray Çaliskan, Market Threads: How Cotton Farmers and Traders Create a Global Commodity (Princeton, 2010). Economic sociology meets global commodity systems. Contains dust-jacket endorsements from Richard Swedberg and Donald MacKenzie, so expect a review from the orgtheory boys soon.

- Peter J. Boettke, ed., Handbook on Contemporary Austrian Economics (Elgar, 2010). Essays by young Austrian economists associated with George Mason University.

- Robert E. Wright, Fubarnomics: A Lighthearted, Serious Look at America’s Economic Ills (Prometheus, 2010). I think the title says it all.

- Ranjay Gulati, Reorganize for Resilience: Putting Customers at the Center of Your Business (Harvard Business School, 2010). Looks fluffy, but I have a teaching interest in change management so I’ll give it the benefit if the doubt.

- David Stark, The Sense of Dissonance: Accounts of Worth in Economic Life (Princeton, 2009). Also deals with organizational change, but in a more serious way. Ethnographic studies of three organizations dealing with large exogenous shocks. Looks interesting.

Random Thoughts on Strategic Entrepreneurship

| Peter Klein |

A few insights, interesting facts, provocative statements, and other things I managed to remember from the conference:

- As Nicolai mentioned in his post below, there is a lot of exciting work out there on the links between organizational design and characteristics (HRM practices, organizational culture, social learning processes, team characteristics, etc.) and entrepreneurial behavior. This is clearly a hot topic at the boundary of the strategic management, organizational behavior, entrepreneurship, and innovation literatures.

- This emerging literature is pretty eclectic, theoretically and empirically. The conference featured papers with formal models, conceptual theory papers, conventional econometric papers, simulation papers, and of course thought-provoking keynote addresses. The participants came from a variety of academic backgrounds and specialty areas.

- It’s a young field. The four keynote speakers (Mike Wright, Bill Schulze, Shaker Zahra, and Jeff Hornsby) are pioneers in the field, and not that old. (Shulze noted that he had been present “at the birth” of the modern entrepreneurship field, and he looks pretty spry and vigorous to me.)

- The empirical literature still struggles to operationalize entrepreneurship in a meaningful way. Despite various sermons about entrepreneurship being a generalized function, rather than a job description or firm type, most empirical papers use self-employment, management of particular kinds of firms, etc. as proxies. (I’m guilty of this myself, of course.) (more…)

The Thin Mint Effect

| Peter Klein |

A new study finds that as nonprofit organizations increase their for-profit activities, the share of resources going to the core mission decreases. (Thanks to Fast Company for the link and the Thin Mint reference.)

A new study finds that as nonprofit organizations increase their for-profit activities, the share of resources going to the core mission decreases. (Thanks to Fast Company for the link and the Thin Mint reference.)

This strikes me as a good illustration of multitask principal-agent problems. The output of for-profit activities is more easily measured than the output of nonprofit activities, giving agents (under performance-based pay) the incentive to increase effort toward those for-profit activities. Mises’s discussion of performance measurement and delegation in Bureaucracy comes to mind as well.

Entrepreneurial Paradoxes

| Peter Klein |

A new working paper from the always-interesting Peter Lewin: “Entrepreneurial Paradoxes: Implications of Radical Subjectivism.” Sample paradoxes:

- Entrepreneurial opportunities are complicated by uncertainty but would not exist without uncertainty.

- An entrepreneurial opportunity for everyone is an opportunity for no one in particular.

- Entrepreneurial opportunities are subjective and objective; discovered and created.

See the paper for the full set of paradoxes and some informative and challenging discussion.

The Legacy and Work of Douglass North

| Peter Klein |

Washington University, St. Louis is hosting a major international conference, 4-6 November, on the Legacy and Work of Douglass North. The all-star panel includes Lee Alston, Robert Bates, Joel Mokyr, Elinor Ostrom, Ken Shepsle, Barry Weingast, and many others. The conference is organized by Wash U’s Center for New Institutional Social Science.

In other conference news, the CFP for next year’s Atlanta Competitive Advantage Conference, 17-19 May 2011, has been posted. Featured presenters include Jay Barney, Joel Baum, and Rebecca Henderson.

The (Very) Early Adoption of Modern HRM Practices

| Peter Klein |

Bruce Kaufman’s book Hired Hands or Human Resources? Case Studies of HRM Programs and Practices in Early American Industry (Cornell U. P., 2010) shows that US firms started adopting “modern” HRM practices around World War I, not during the New Deal, and they did so primarily to increase productivity, not in response to union or government pressure. Writes reviewer Chad Pearson:

Kaufman illustrates the ways in which several companies created professional human resource management (HRM) models after World War I. This is the most valuable part of the book principally because he used the records of the Industrial Relations Councilors (IRC), a consulting firm that began assisting employers in the 1910s. The IRC offered consulting services, provided research, and ran courses on industrial relations topics throughout the nation. Kaufman, the first scholar to examine these records, believes that “no other [industrial relations consulting firm] before World War II had IRC’s reach and influence” (p. 108). . . .

In most cases, these firms, in consultation with the IRC, began to, in Kaufman’s words, treat labor not as “a short-term commodity,” as was common in previous decades, but rather as “a longer-term human capital asset (the ‘human resource’ approach)” (p. 219). Why? Pressure from unions and the law were factors, but “they were less than half the story in the time period we are examining” (p. 228). In his view, employers’ desires to improve “management and productivity” better explain why companies improved workplace conditions (p. 227).

Labor historians and specialists in business regulation used to focus on the Progressive Era as a watershed period — e.g., Wiebe (1962), Weinstein (1981), and of course Kolko (1977) — but interest seems to have waned.

Elgar Companion to TCE

The Elgar Companion to Transaction Cost Economics, edited by Mike Sykuta and me, has just been published. Twenty-nine chapters cover the basic structure of TCE, its precursors and influences, fundamental concepts, applications and evidence, along with alternatives and critiques. Oliver Williamson was kind enough to contribute an introduction and overview. Co-blogger Foss is in there as well.

O&M readers can get it here 10 percent off the list price! (Actually, anybody can get the deal.) Mike beat me to the punch with an announcement and description, so I’ll just add that we’re really pleased with the final product and grateful to all the distinguished contributors and the production staff.

Here are previous O&M posts on transaction cost economics.

Recent Comments