Posts filed under ‘Myths and Realities’

More on Blind Freddy

| Steve Phelan |

Apologies to everyone for my lengthy absence. Since January 1, I have been working in a new administrative role in the College of Business at UNLV {shock, horror}. (Details can follow after a formal announcement is made).

Further to my argument several months ago that “blind freddy” could have seen the mortgage problems, here is a nice insider view from Calculated Risk:

But a whole lot of these loans that are failing right now were originated as 100% CLTV stated-income loans, because the guidelines agreed to by the issuer allowed that. I am scratching my head over the logic here: I spent most of the early years of this decade, just as a for instance, blowing my blood pressure to danger levels every time I looked at the underwriting guidelines published by ALS, the correspondent lending division of Lehman. ALS was a leader in the 100% stated income Alt-A junk. And I kept having to look at them because my own Account Executives keep shoving them under my nose and demanding to know how come we can’t do that if ALS does it. I’d try something like “because we’re not that stupid,” and what I’d get is this: “But if ALS can sell those loans, so can we. All we gotta do is rep and warrant that they meet guidelines that Wall Street is dumb enough to publish.” Every lender in the boom who sold to the street wrote loans it knew were absurd, but in fact they had been given absurd guidelines to write to. What on earth good did it do to have those originators represent and warrant that they followed underwriting guidelines to the letter, when those guidelines allowed stated income 100% financing on a toxic ARM with a prepayment penalty?

The argument is that mortgage originators were not so much committing massive fraud but rather that banks were following lax guidelines that those on ‘the Street’ did not view as problematic (or perhaps that the ultimate investor did not view as problematic).

Medieval Business Schools

| Peter Klein |

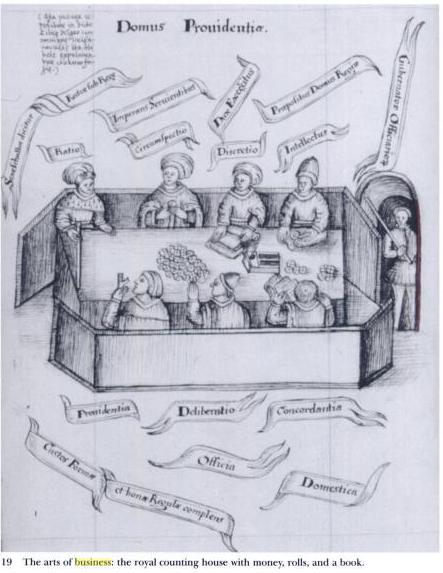

Contrary to popular belief, formal education in medieval times was not restricted to the clergy and the very wealthy. Nor was theology the most popular subject. Independent schools, unaffiliated with any particular religious body or royal institution and staffed by lay people, were common, and even taught business administration (writing letters, drafting contracts, keeping the books).

So says Nicholas Orme in Medieval Schools: From Roman Britain to Renaissance England (Yale, 2006). (Thanks to Tom Woods for the pointer.) In Britain, grammar schools were often supported by wealthy patrons and were open to students of modest means. Notes Orme:

Most [English] schoolmasters were probably broad rather than specialized teachers, catering for a wide range of needs, so it is not surprising that a brand of practical teacher emerged by the fourteenth century (at latest), offering more focused instruction for careers in trade and administration. Such instruction might include “dictamen” (the art of writing letters), the methods of drafting deeds and charters, the composition of court rolls and other legal record, and the keeping of financial accounts. Since documents of these kinds were often written in French between 1200 and 1400, the practical teachers came to teach French too.

This illustration, from p. 69 of the book, depicts such a class. How did they do it without PowerPoint?

Shane Interview in Business Week

| Peter Klein |

Scott Shane is interviewed in today’s Business Week on his new book, The Illusions of Entrepreneurship. The book is a treasure-trove of empirical data on startups, much of which is familiar to specialists but completely unknown in the business press and in popular culture (e.g., that industry explains most of the variation in failure rates). See also this guest post by Scott on Guy Kawasaki’s blog for more on the basic thesis.

Of course, when Scott writes here about the value of entrepreneurship to society defines entrepreneurship narrowly as busines startups, not some broader notion of creativity, innovation, alertness, or (to ride one of this blog’s favorite hobby-horses) judgment.

Brain Flows

| Steve Phelan |

Further to my comments on the best and brightest entering the finance industry, David Wessell at the WSJ reports that 15% of male Harvard graduates from 1990 work in the finance industry compared with only 5% of 1970 graduates. Furthermore, those Harvard grads in the finance industry were earning 195% of the salary of those in other industries. The article later goes on to state that “some of the brainpower drawn to Wall Street would have been more productively employed elsewhere in the economy.” The question is whether all this is a free market outcome or is some sort of distortion misallocating resources?

Prediction markets

| Steve Phelan |

One of the memes rattling round the blogosphere today is the failure of prediction markets to predict Hillary Clinton’s win in New Hampshire – in fact, to radically write off her prospects after the Iowa outcome. Paul Krugman goes so far as to entitle his blog on the subject “nobody knows anything” (as opposed to Surowiecki’s wisdom of crowds).

Surowiecki argues that wise crowds need: a) diversity of opinion, b) independence, c) decentralization (i.e. local knowledge), and d) a mechanism to aggregate private judgments. Which leads me to ask: What is the missing element in prediction markets? To the degree that investors in prediction markets are receiving their information from common national media sources then it would seem that diversity, independence, and decentralization are missing.

My Pet Peeve

| Steve Phelan |

One of my pet peeves is when academics assume that people in industry are a little “dim.” For instance,

It would be churlish to point out that the fact that one should be extremely leery of arguments that diversification radically improves the safety of bond investments was well known back by Edgar L. Smith and others back in 1923.

This quote from Brad De Long here.

I’m not picking on Brad because it happens quite a bit in my experience. The “oh my gosh, we academics have known since 1923 that diversification of bonds does not reduce systematic risk that much, you dumbasses.”

Contrast this view with the fact that the brightest minds in a generation have been taking jobs on Wall Street. So the smartest people are the biggest dumbasses???

In these matters, I prefer to assume plausible deniability. Reducing systematic risk by combining geographically diversified BBB bonds sounds just plausible enough to avoid litigation for fraud and/or negligence. Now that’s smart!

More Econ Bashing

| Nicolai Foss |

A topic that has frequently been discussed on O&M is the bashing of economics that appears to have become a favorite pastime of management writers such as Jeffrey Pfeffer, Henry Mintzberg, (the late) Sumantra Ghoshal, and others (e.g., here, here, and here). The most radical statement of that recent wave is the Ferraro, Pfeffer, and Sutton 2005 paper in the Academy of Management Review (here is a selection of O&M posts on this paper). Or, so we thought …

Max Bazerman and Deepak Malhotra, both of Harvard University, have contributed a chapter, tellingly titled “Economics Wins, Psychology Loses, and Society Pays,” to a recent edited volume, Social Psychology and Economics (check Herbert Gintis’ review of the book on Amazon) (here is the Google copy). What they say is so uncompromising (and cranky) that it has to be read to be believed. Here is a sample:

Recent history has witnessed the financial distress of companies such as Enron, Adelphia, Global Crossing, Halliburton, Xerox, Worldcom and Tyco. Millions of jobs and tens of millions of retirement plans have been lost. Shortcomings in U.S. security policies were at least partially responsible for the tragedies involved with 9/11. Eleven of the 17 major fisheries in the world are commercially extinct. The United States needlessly allows thousands of people to die each year because of an ill-conceived organ donation system. Behind each of these disasters is the hand of economic logic, the dominance of this logic to the exclusion of other useful social sciences (p.264).

The solution? A Council of Psychological Advisers to parallel (or trump?) the Council of Economic Advisers. Yes, that’s right.

Financial Innovation

| Steve Phelan |

In his recent NY Times op-ed, Paul Krugman railed against the evils of financial innovation:

How did things get so opaque? The answer is “financial innovation” — two words that should, from now on, strike fear into investors’ hearts.

O.K., to be fair, some kinds of financial innovation are good. . . . But the innovations of recent years — the alphabet soup of C.D.O.’s and S.I.V.’s, R.M.B.S. and A.B.C.P. — were sold on false pretenses. They were promoted as ways to spread risk. . . . What they did instead — aside from making their creators a lot of money, which they didn’t have to repay when it all went bust — was to spread confusion, luring investors into taking on more risk than they realized.

Folsom’s (1991) “Myth of the Robber Barons” contrasts “political entrepreneurs,” who basically engage in rent-seeking, from “market entrepreneurs,” who seek entrepreneurial rents and improve social welfare. (HT: Rafe Champion.) I’m wondering if we need a new category of entrepreneurs?

(more…)

Teaching Social Responsibility

| David Hoopes |

I am on the planning committee and the goals committee here at Cal State Dominguez Hills. At a recent meeting it came up that one of the schools goals was academic excellence and social responsibility. I suggested that they are two very different topics but was roundly rebuked. I have a few problems with considering social responsibility to be part of the same goal as academic excellence for college professors.

My first complaint is that “social responsibility” is not very easy to define or operationalize. Usually, it seems to imply donating money to some left wing cause. I might be able to find some left wing causes I like. However, I’m not sure how teaching students to tithe is similar to teaching students a course of study or an academic discipline.

My second complaint is that I don’t think academicians are qualified to teach social responsibility. I admit to being jaded and cynical. But I do not find academicians to be shining examples of virtue. Getting a Ph.D. in management, economics, or sociology hardly qualifies one to determine what students should consider to be socially virtuous.

I do think colleges (especially state funded) have some obligation to promote citizenship and promote and encourage ethical and moral behavior. Additionally, I am very happy to have those who specialize in ethics and related topics to teach them (the philosophy department?).

However, again, I don’t see this as our primary mandate. I might feel better about this if I felt that academics were paragons of ethical and moral behavior. On the contrary, I am continually disappointed in the standards to which academicians hold themselves. Having worked a variety of odd and not so odd jobs before heading to the academy I feel pretty comfortable saying that academicians certainly do not appear to have superior ethical and moral behavior.

What, you might ask, makes me think of academics as being ethically or morally lacking? Well that’s for another post.

Deconstructing Bob and Jeff

| David Hoopes |

For better or worse the hard-hearted authors at O&M have hurt the feelings of our colleagues in other fields. In the spirit of being more specific about why the bloggers here are so harsh I’d like to take a look at an award-winning paper from the Academy of Management Review (Ferraro, F., Pfeffer, J., and Sutton, R.I., “Economics Language and Assumptions: How Theory Can Become Self-Fulfilling”). In this paper we are told how the language of economics (the assumptions that people are selfish cheats) encourages people to be selfish cheats. Aside: in my opinion sociologists have a much darker image of humankind than economists (if we must make careless generalizations).

As I note in an earlier post, the idea of self-interest is often grossly misrepresented. Perhaps economists can thank themselves for this. I don’t know. However, it is important to examine this component of price theory by looking at its roots. In developing public policy toward government intervention in the allocation of goods (mercantilists vs. free traders in Smith’s day) allowing people to make their own decisions is more efficient than having a handful of people making the decisions for everyone. And even if individuals focus on their own needs the result for society is better than having a few people guessing at what everyone else wants and imposing their guesses.

The starting point of the AMR critique is the ever-present complaint about the economics world telling us all that we need to be selfish and greedy (make decisions based on our own self-interest). From here, our friends in the org. theory camp state, “If people are relentless in the pursuit of their own self-interest and equally relentless in the their lack of concern for others’ interests. . . .” What? Where did that second part come in? A very important bridge theory has been added. If people pursue their own self-interest then they also cannot care about anyone else. Management scholars wonder why their (our) work is not used in public policy debates. Small wonder. (more…)

Agency Theory and Intrinsic Motivation

| Nicolai Foss |

Agency theory represents one of the most influential and controversial bodies of microeconomics. To some, it is an extraordinarily powerful theory that can be applied in all sorts of ways and provides the theoretical foundation for the understanding of reward systems, many contractual provisions, the use of accounting methods, corporate governance, etc. To others (e.g., Bob, Jeff, and Alfie), it is the brainchild of overly cynical economists, responsible for most evil in the World, including bad managerial practices and Enron. (more…)

Why Are Markets So Scary? Some Things (Liberal) Academics Get Wrong

| David Hoopes |

Many people make incorrect assumptions about capitalism. Some would have us believe that capitalism is based on greed, selfishness, and promotes behavior that is completely self-centered. This is a common interpretation of Smith’s advice to allow people to make decisions based on self-interest. Examples are easy to find in the many organization theory-based papers complaining about economics and economists.

Two very good papers can aid in a deeper understanding of the invisible hand. First is James Q. Wilson’s “Adam Smith on Business Ethics.” A central point Wilson makes is that Adam Smith assumed people will behave with a moral sense. Wilson, “A moral man is one whose sense of duty is shaped by conscience; that is, by that impartial spectator within our breast who evaluates our own actions as others would evaluate it.” By suggesting people be allowed to make decisions based on their own self interest Smith was not advocating selfishness and greed. What then was he advocating?

This leads to the second paper, Harold Demstez’s “The Theory of the Firm Revisited.” In the third paragraph Demsetz notes that the debate between mercantilists and free traders was over the role of the government in the economic affairs of the state. “Is central economic planning necessary to avoid chaotic economic conditions?” The great achievement of the perfect competition model, what Demsetz argues should be called perfect decentralization, is its abstraction from centralized control of the economy.

Thus, the central element to capitalism is that decision making is pushed down as far as possible. (more…)

Innovation Without Patents

| Nicolai Foss |

While public policy-makers (and students) exalt patents, scholars in strategic management and innovation studies tend to take a much more balanced view. They know that the use of patents tend to concentrate in relatively few industries, and that in many cases alternative mechanisms are superior means of appropriating rent streams from innovations (e.g., this paper). Of course, libertarians, including libertarian economists, have long harbored skepticism towards the patent system, including skepticism based on efficiency arguments. Now economic historians seem to add to patenting skepticism. (more…)

Mental Illness in the Academy: Elyn Saks’ Brave New World

| David Hoopes |

Monday’s LA Times had an amazing story about a USC law professor who has managed to attend Oxford, Yale Law School, and become Dean of Research at the USC law school while battling schizophrenia. Many O&M readers have probably read the book or seen the movie, “A Beautiful Mind,” the incredible story of mathematician John Nash. Like Nash, Elyn Saks suffered hallucinations, delusions, and a litany of other terrible effects of her disease. I probably should not use the past tense because I don’t believe medicine can remove these things. However, they can be tempered. Saks recently published a memior, “The Center Cannot Hold: My Journey Through Madness.” Thus, in addition to the direct suffering of the disease, Saks is now willing to take on the problems of social stigma, no small thing.

I wish I could think of some profound comment or lesson. There are many among us who suffer from a variety of mental illnesses. For better or worse, more jokes about academics come to mind than profundities. Here’s to the day when the social stigma associated with mental illness is much smaller. I’ve always thought I’d wait until I got tenure to open up any of my (much more minor) nightmares.

The Best Business Book I’ve Read This Year

| Peter Klein |

It’s Phil Rosenzweig’s The Halo Effect (mentioned previously here). Rosenzweig systematically, but politely, demolishes the pretensions of best-selling management books and projects such as In Search of Excellence, Built to Last, Good to Great, and the Evergreen Project. These studies, Rosenzweig patiently explains, engage not in serious research — despite their pseudo-scientific pretensions (what Rosenzweig calls “The Delusion of Rigorous Research”) — but in storytelling.

The most common problems are sampling on the dependent variable (i.e., choosing a sample of high-performing companies and explaining what their managers did, ignoring selection bias) and using independent variables based purely on respondents’ ex post subjective assessments of strategy, corporate culture, leadership, and other “soft” characteristics. The latter is the “Halo Effect” of the book’s title. When a company’s financial or operating performance is strong, managers, consultants, journalists, and management professors tend to rate strategy, culture, and leadership highly, while rating the same strategies, cultures, and leadership poorly when a company’s performance is weak. It’s as if the authors of “guru” books have never taken a first-year graduate course on empirical research design. Or, as Rosenzweig puts it (p. 128): “None of these studies is likely to win a blue ribbon at your local high school science fair.” Ouch. (more…)

Who Are Those Young Libertarian Org Scholars?

| Nicolai Foss |

In his keynote address to the 2006 meeting in Bergen (Norway) of the European Group for Organizational Studies, Jim March notes that “European organization studies were influenced deeply by the fact that expansion occurred in the decades following the protest and counterculture movements of the 1960s and 1970s . . . [as seen] . . . in such things as qualitative research on culture, gender, sense-making, social construction and power” (p. 14). (more…)

Incoherence Is Bad For You but Good For Us

| Steven Postrel |

I just finished reading David Hull’s remarkable Science as a Process (1988), and was struck by one of his arguments. One of his claims (not his major thesis) is that while each scientist strives to make his own work coherent and internally consistent, overall progress only occurs because the views of every school of thought and every discipline are somewhat incoherent. (more…)

Tulip Mania: Not So Manic After All

| Peter Klein |

Popular and scholarly accounts of the Dutch tulip bubble of 1636-37 — including Robert Shiller’s — greatly exaggerate the magnitude of the crisis. It seems the tulipmania literature tends to rely not on primary sources or other authoritative documents but on popular pamphlets that appeared shortly after the crisis, designed to ridicule tulip-market participants.

So says Larry Neal, reviewing Anne Goldgar’s Tulipmania: Money, Honor, and Knowledge in the Dutch Golden Age for EH.Net. Goldgar’s careful archival research demonstrates, among other things, that tulip-market participants were not hapless dupes but experienced merchants who knew how to price risks and who were part of a small, close-knit community that relied on strong social ties to enforce good behavior. Indeed, tulip transactions were highly complicated ones governed by detailed contractual arrangements designed to protect both buyers and sellers. Goldgar “notes that the participants in the tulipmania largely worked out the terms of the broken contracts among themselves with little impact on the rest of the Dutch economy. . . . So the tulip trade in Holland revived and continued to prosper, as it does to this day.”

Are Economists Free-Market Apologists?

| Peter Klein |

This New York Times piece describes contemporary economics as a rigid free-market orthodoxy, challenged by a few courageous iconoclasts who question free trade, support minimum wages, favor tax and spending increases, and the like. To the author: What color is the sky on your planet?

I was to blog a more detailed reaction but Alex Tabarrok, Larry White, and Greg Mankiw, among others, have beaten me to it. Note that Alex and Larry both refer to Dan Klein’s work on the ideological views of economists, which we’ve discussed often here at O&M. The Times piece did not bother to include any data, of course.

Adam Smith and the Corporation

| Peter Klein |

Larry Elliott writes in the Guardian that Adam Smith would oppose the modern shareholder model of the corporation. Smith, he argues, “would have looked askance at an economy gripped by speculative fever, with the emphasis not on making things but on buying and selling, making a turn, churning, taking a punt, sweating an asset.” Leaving aside for the moment that the distinction between “making” and “buying and selling,” as used here, is entirely specious, is this a fair interpretation of Smith? Elliott continues:

Smith, indeed, predicted what might happen in the Wealth of Nations, when he supported the idea of private companies (or copartneries) against joint stock companies, the equivalent of today’s limited liability firm. In the former, Smith said, each partner was “bound for the debts contracted by the company to the whole extent of his fortune”, a potential liability that tended to concentrate the mind. In joint stock companies, Smith said, shareholders tended to know little about the running of the company, raked off a half-yearly dividend and, if things went wrong, stood only to lose the value of their shares.

“This total exemption from trouble and from risk, beyond a limited sum, encourages many people to become adventurers in joint stock companies who would, upon no account, hazard their own fortunes in any private copartnery. The directors of such companies, however, being the managers rather of other people’s money than their own, it cannot well be expected that they should watch over it with the same anxious vigilance with which the partners in a private copartnery frequently watch over their own.” (more…)

Recent Comments