Posts filed under ‘Myths and Realities’

Fast Food and Obesity

| Peter Klein |

A new Australian public-service ad compares fast food to heroin: “You wouldn’t inject your children with junk. So why are you feeding it to them?” (See the ad, along with Katherine Mangu-Ward’s funny meditations on the theme.) But does fast food really contribute to health problems, particularly obesity?

A new Australian public-service ad compares fast food to heroin: “You wouldn’t inject your children with junk. So why are you feeding it to them?” (See the ad, along with Katherine Mangu-Ward’s funny meditations on the theme.) But does fast food really contribute to health problems, particularly obesity?

Not much, according to Richard Dunn’s study, “The Effect of Fast-Food Availability on Obesity: An Analysis by Gender, Race, and Residential Location,” in the July 2010 issue of the American Journal of Agricultural Economics (it’s peer reviewed, and not funded by corporations!). Previous research finds links between the number and density of fast-food restaurants and health problems, but has difficulty identifying cause and effect (fast food could make people overweight, but fast food restaurants could be put in areas where people are overweight anyway). Dunn uses the number of interstate exits as an instrument for restaurant location to tease out the causal relations, and finds little overall effect of fast food on obesity — none at all in rural areas, a bit in medium-density areas, and only among women and minorities.

The Peer-Review Fetish

| Peter Klein |

I respect peer review as much as the next person and have done my share of publishing in peer-reviewed outlets. But I question the belief, expressed often in academic, media, and policy circles, that “not peer reviewed” means “worthless” and “peer reviewed” means “should be accepted without question.” (A corollary belief is that “funded by a private foundation or company” means “biased” while “funded by a government grant” means “neutral.”) In practice, the distinctions are not nearly so clean.

My thoughts on this were triggered by a revealing statement from Ronald Coase, quoted by Josh Gans and George Shepherd in their study of famous economics papers that were initially rejected, about his limited experience with peer review: “I have never found any difficulty in getting my articles published. I have either published in house journals (e.g. Economica) or the article was written as a result of a request (e.g. for a conference) and publication was assured.” Certainly no one would discount the importance Coase’s 1937 and 1960 papers because they weren’t rigorously peer reviewed. (Can you imagine the inane referee remarks that “The Problem of Social Cost” would have generated?) More generally, consider the Journal of Law and Economics during Coase’s editorship in the 1960s and 1970s — the high-water mark of the JLE‘s influence. Or, for that matter, Public Choice under Gordon Tullock, the JPE under George Stigler, or the Journal of Libertarian Studies under Murray Rothbard. These were edited somewhat unevenly, led by charismatic and strong-willed editors with idiosyncratic tastes, yet have been vastly influential in their respective fields.

Peer review serves a useful function and probably improves the quality of published output, on average. But let’s not make a fetish of it.

The Myth of the Razors-and-Blades Strategy

| Peter Klein |

| Peter Klein |

Not quite as exciting as the GM-Fisher contretemps, but in the same revisionist vein: Randy Picker’s new paper, “The Razors-and-Blades Myth(s).”

From 1904-1921, Gillette could have played razors-and-blades — low-price or free handles and expensive blades — but it did not do so. Gillette set a high price for its handle — high as measured by the price of competing razors and the prices of other contemporaneous goods — and fought to maintain those high prices during the life of the patents. For whatever it is worth, the firm understood to have invented razors-and-blades as a business strategy did not play that strategy at the point that it was best situated to do so.

Here’s a PPT version.

Well, as Bogey might have said to Bergman: “We’ll always have printer ink.”

Department of “Duh”

| Peter Klein |

It must be acknowledged, however, that a researcher’s political ideology or vested interest in a particular theory can still enter even ostensibly descriptive analysis by the data set chosen for the research; the mathematical transformations of raw data and the exclusion of so-called outlier data; the specific form of the mathematical equations posited for estimation; the estimation method used; the number of retrials in estimation to get what strikes the researcher as “plausible” results, and the manner in which final research findings are presented.

That’s Uwe Reinhardt, writing a NY Times op-ed that could have been titled “A Mainstream Economist Tries to Come to Grips with Kaldor-Hicks Efficiency.” It’s actually a pretty thoughtful and informative discussion that exposes some of the fatal — to my mind, anyway — flaws of the Kaldor-Hicks concept. But Reinhardt implies, unfortunately, that virtually every economist accepts the Kaldor-Hicks principle as a normative standard. There is actually a fair amount of dissent, not only from Austrians but also from people like Jon Elster and John Roemer. As Gary Lawson notes in an excellent survey of welfare economics concepts, the Kaldor-Hicks criterion, in practice, is

as useless as Pareto superiority. Kaldor-Hicks efficiency purchases its coherence by requiring that compensation be hypothetically possible in such a way as to guarantee that each person, by her own standards, does not come away a loser, just as strict Paretianism requires that each person judge herself to be as well off or better off than before. All it takes to make the universe of Kaldor-Hicks-efficient transactions an empty set is one person who sincerely cannot be bought-that is, a person who values autonomy, either his own or that of others, so highly that no amount of after-the-fact compensation could possibly leave him as well off as he would have been had the loss never been inflicted. (without consent) in the first place. In a large population, no legal rule [or other reallocation of resources] will ever satisfy the Kaldor-Hicks efficiency criterion.

The Corporate Hierarchy Dies, Again

| Peter Klein |

Ronald Coase described his 1937 paper on the firm as “much cited, but little used.” He was referring to the academic literature, but these days it seems to apply to the popular press as well. Almost every week brings a new article on the death of the corporate hierarchy: you know, firms only exist to deal with transaction costs, and the Internet has reduced them to almost zero, so who needs firms? This argument shows up again and again. But it’s wrong. Of course there are transaction costs between firms (search, bargaining, enforcement). But there are also transaction costs inside firms (agency and information costs, the Misesian calculation problem). The firm straddles these margins. Both sets of transaction costs matter, and both can be reduced through technological change. Coase was not as clear on this point as he could have been, but Williamson has been explaining it for decades, in terms of “comparative contracting costs.” You have to compare both sets of costs, not just look at one. Why is it so hard to see?

Saturday’s WSJ gives us the latest version of the bogus argument, this time from Alan Murray. Same old story: Internet, transaction costs, Tapscott and Williams, wikipedia, yada yada yada. “Mr. Coase received his Nobel Prize in 1991 — the very dawn of the Internet age. Since then, the ability of human beings on different continents and with vastly different skills and interests to work together and coordinate complex tasks has taken quantum leaps. Complicated enterprises, like maintaining Wikipedia or building a Linux operating system, now can be accomplished with little or no corporate management structure at all.” Yawn. “[T]he trends here are big and undeniable. Change is rapidly accelerating. Transaction costs are rapidly diminishing. And as a result, everything we learned in the last century about managing large corporations is in need of a serious rethink.” Zzzzzzzzzzzzzzz. Mr. Murray, please read The Victorian Internet three times fast and have a report on my desk first thing in the morning. “The new model will have to be more like the marketplace, and less like corporations of the past. It will need to be flexible, agile, able to quickly adjust to market developments, and ruthless in reallocating resources to new opportunities.” Right, no corporations of the past ever tried to do this.

Add to: Facebook | Digg | Del.icio.us | Stumbleupon | Reddit | Blinklist | Twitter | Technorati

The Organizational Economics of the BP Oil Spill

Now that passions are cooling regarding the BP disaster, it’s time to bring organizational issues into the discussion.

1. Everyone knows about the liability caps and the role they may have played in encouraging moral hazard. Just as bank deposits are guaranteed by government deposit insurance, and large banks themselves are probably Too Big to Fail, liability for property damage from oil spills off US waters is limited to $75 million (plus cleanup costs), based on a 1990 law passed after the Exxon Valdiz spill. This presumably mitigates drillers’ incentives to manage environmental risk. Indeed, oil companies enjoy a very cozy relationship with their ostensible guardians; as the NY Times noted, “[d]ecades of law and custom have joined government and the oil industry in the pursuit of petroleum and profit.” The federal agency that oversees drilling, the Minerals Management Service, rakes $13 billion a year in fees in what amounts to a public-private partnership. And does anyone really think the British government would “stand idly by” if BP’s status as an ongoing concern were threatened by criminal or civil penalties?

2. As Bill Shughart points out, BP did not own the Deepwater Horizon platform, but leased it from a company called Transocean. To Bill this suggests “a classic principal-agent problem in which the duties and responsibilities of lessor and lessee undoubtedly were not spelled out fully, especially with respect to maintenance and testing of the rig’s blowout preventer as well as to the advisability of installing a second ‘blind sheer ram,’ which may have been able to plug the well after the first (and only one then in service) failed to do so.” Would BP have paid more attention to safety if it owned, rather than leased, the platform? (more…)

Political and Methodological Individualism

| Peter Klein |

Further to Nicolai’s post, it is also widely believed that methodological individualism — the chief explanatory principle of economics and rational-choice sociology and political science — implies or justifies political individualism or, even worse, some kind of metaphysical or ontological individualism. “But people are social beings!” cry the critics. Well, sure. Methodological individualism is simply the view that social phenomena should be explained, or understood, in terms of the values, beliefs, plans, and actions of the individual that make up the social whole. It makes no claims about the ultimate source of these values and beliefs, the degree to which people are influenced by society, etc. It is a principle of explanation, nothing more.

Further to Nicolai’s post, it is also widely believed that methodological individualism — the chief explanatory principle of economics and rational-choice sociology and political science — implies or justifies political individualism or, even worse, some kind of metaphysical or ontological individualism. “But people are social beings!” cry the critics. Well, sure. Methodological individualism is simply the view that social phenomena should be explained, or understood, in terms of the values, beliefs, plans, and actions of the individual that make up the social whole. It makes no claims about the ultimate source of these values and beliefs, the degree to which people are influenced by society, etc. It is a principle of explanation, nothing more.

Here’s a plain statement from Schumpeter, the guy who coined the term “methodological individualism” (okay, he used methodische Individualismus, and borrowed the concept from Weber), writing in 1908:

[W]e must strictly differentiate between political and methodological individualism, as the two have virtually nothing in common. the former starts form the general assumption that freedom, more than anything, contributes to the development of the individual and the well-being of society as a whole and puts forward a number of practical propositions in support of this. The latter is quite different. It has no specific propositions and no prerequisites, it just means that it bases certain economic processes on the actions of individuals. Therefore the question really is: is it practical to use the individual as a basis and would there be enough scope in doing so, or would it be better, in view of specific problems and the national economy as a whole, to use society as a basis. This question is purely methodological and involves no important principle. The socialists can answer it in terms of methodological individualism and the political individualists in terms of their social concept of things, without getting into conflict with their convictions.

See also the Mises quotes discussed here.

Add to: Facebook | Digg | Del.icio.us | Stumbleupon | Reddit | Blinklist | Twitter | Technorati

The History of Nikola Tesla

| Peter Klein |

Saturday was Nikola Tesla’s birthday. Here’s Jeremiah Warren’s video in Tesla’s honor:

Tesla was, of course, the great inventor whose technical achievements outshone those of his great rival, Thomas Edison, but who was unable to commercialize any of his discoveries. Tesla, unfortunately, put his faith in intellectual property-rights protection, while Edison emphasized management and marketing. As Danny Quah puts it, “Public relations and entrepreneurial savvy trump the raw intellectual idea.”

Add to: Facebook | Digg | Del.icio.us | Stumbleupon | Reddit | Blinklist | Twitter | Technorati

Pomo Periscope XX: Thomas Basbøll vs. Karl Weick

| Nicolai Foss |

Karl Weick may not really qualify as a bona fide pomo. He writes well and clearly and much of his work is quite in the mainstream of management research. Still, he has written about the favorite pomo notion of reflexivity (e.g., here), his authority is often invoked in prominent pomo tracts in management (e.g., here), and his notion of sensemaking has a distinct pomo connotation.

Weick’s work has recently been subject to close examination by my CBS colleague, Thomas Basbøll. In a recently published paper, “Softly Constrained Imagination: Plagiarism and Misprision in the Theory of Organizational Sensemaking,” Basbøll argues that Weick’s work suffers from “significant instances of plagiarism and misreading” (p. 164). Wow! Here is the abstract:

While Karl Weick’s writings have been very influential in contemporary work on organizations, his scholarship is rarely subjected to critical scrutiny. Indeed, despite its open ‘breaching’ of the conventions of much academic writing, Weick’s work has been widely celebrated as ‘first-rate scholarship.’ As it turns out, however, his ‘softly constrained’ textual practices are rendered doubtful by both misreading and plagiarism, which makes his work resemble ‘poetry’ in a much stronger sense than perhaps originally intended. This paper draws inspiration from literary theory to analyze three cases of questionable scholarship in Weick’s 1995 book Sensemaking in organizations, framing them in the context of standard formulations of the methodology of sensemaking drawn from the literature. It concludes that we need to rethink our tolerance of the sensemaking style and re-affirm a commitment to more traditional academic constraints.

Here is Weick’s reply. And here is Thomas’s reply to the reply.

Add to: Facebook | Digg | Del.icio.us | Stumbleupon | Reddit | Blinklist | Twitter | Technorati

Does Behavioral Economics Offer Anything New and True?

| Peter Klein |

One of my frustrations with behavioral economics is that it often seems to restate common, obvious, well-known ideas as if they are really novel insights (e.g., that preferences aren’t stable and predictable over time). More novel propositions are questionable at best (e.g, the paradox of choice).

Dan Ariely’s column in this month’s HBR is particularly frustrating. He claims as a unique insight of behavioral economics that when people are evaluated according to quantitative measures of performance, they tend to focus on the measures, not the underlying behavior being measured. Well, duh. This is pretty much a staple of introductory lectures on agency theory (and features prominently in Steve Kerr’s classic 1975 article). Ariely goes on to suggest that CEOs should be rewarded not on the basis of a single measure of performance, but multiple measures. Double-duh. Holmström (1979) called this the “informativeness principle” and it’s in all the standard textbooks on contract design and compensation structure (e.g., Milgrom and Roberts, Brickley et al., etc.) (Of course, agency theory also recognizes that gathering information is costly, and that additional metrics are valuable, on the margin, only if the benefits exceed the costs, a point unmentioned by Ariely.)

Ariely says firms should not evaluate CEO’s on stock price, but on a variety of measures. What, for example? Here the story gets a bit murky:

Ideally, they’d vary by industry, situation, and mission, but here are a few obvious choices: How many new jobs have been created at your firm? How strong is your pipeline of new patents? How satisfied are your customers? Your employees? What’s the level of trust in your company and brand? How much carbon dioxide do you emit?

Ariely seems unaware that stock price is the most frequently used measure of firm performance precisely because it is a composite measure that captures all of those things. Stock price reflects the best available information about current and expected future performance — products, jobs, customer satisfaction, etc. Is it a perfect measure? Hardly. But it isn’t obvious how owners or Boards can create their own quantitative, composite measure by by picking their favorite elements, proxies, weighting schemes, and so on, in a way that provides better overall assessments of performance than market valuations. Boards, after all, may be predictably irrational too.

Add to: Facebook | Digg | Del.icio.us | Stumbleupon | Reddit | Blinklist | Twitter | Technorati

Manne on Fama and French

| Peter Klein |

An open letter to Gene Fama and Ken French from Henry Manne (also running today at Truth on the Market):

Dear Gene and Ken:

I must say that I was totally flabbergasted when I read your recent blog posting on insider trading. I know that your usual posts on investments, which I often cite to friends, are well-informed and empirically supported; your work over the years on these topics is important and influential — and rightly so. Unfortunately, in this post, you have deviated from your usual high quality. Anyone current on the topic of insider trading will recognize that you have been careless in your selection of anti-insider-trading arguments and that you omitted from your brief note the major part of the argument about insider trading: whether and how much it contributes to market efficiency. To say this is a strange omission coming from Fama and French would be an understatement.

Your first error is to assume that the insider trading debate is about informed trading only by “top management.” I suspect that this error may flow from my original argument for using insider trading to compensate for entrepreneurial services in a publicly held company, a matter you do not mention and which I will not pursue here except to note that “entrepreneurial services” does not equate to top management. Strangely no one seems to notice that most of the celebrated cases on the subject have not involved corporate personnel at all (a printer, a financial analyst, a lawyer, and Martha Stewart). (more…)

Raising Rivals’ Costs, Goldman Edition

| Peter Klein |

One could also call this “From the Department of ‘Duh'”:

A powerful alumni network plus bundles of campaign cash mean Goldman will get what it wants — and contrary to the media narrative, what Goldman wants is not laissez-faire.

Politico quoted a Goldman lobbyist Monday saying, “We’re not against regulation. We’re for regulation. We partner with regulators.” At least three times in Goldman’s conference call Tuesday, spokesmen trumpeted the firm’s support for more federal control. . . .

Goldman reported on the conference call that it holds 15 percent “Tier 1 capital,” meaning it is very liquid and not very risky. Goldman can play it safe, you see, without needing a regulation. But regulations prevent smaller competitors from taking the risks needed to compete with Goldman (and every competitor is smaller).

The article is also very good on Obama’s Goldman problem. (Link from Steve Horwitz via Per Bylund.)

Add to: Facebook | Digg | Del.icio.us | Stumbleupon | Reddit | Blinklist | Twitter | Technorati

IRB Flames

| Peter Klein |

Zachary Schrag’s excellent Institutional Review Blog highlights the discussion on a recent Chronicle post about IRBs. As you can imagine, most of the comments are from frustrated researchers who see the campus IRB as their enemy, not their ally. Sample: “At my current institution, humanities scholars are subject to an IRB that only makes sense for scientists collecting blood and doing life-threatening experiments on small children.” Zach points out that a few comments defend the local IRB, but these comments “are vaguer and less eloquent,” and “none tells a story of an IRB review that proved necessary.”

I suspect that some of this researcher frustration can be alleviated by recognizing that IRBs exist not to protect research subjects, but to protect the university. The IRB’s goal is to prevent the university from being sued or otherwise losing Federal funding. Protecting research subjects, improving research methods, and contributing to the growth of knowledge are incidental.

Add to: Facebook | Digg | Del.icio.us | Stumbleupon | Reddit | Blinklist | Twitter | Technorati

Why Are the Dutch So Clean?

| Nicolai Foss |

Folk wisdom holds that people stopped bathing after the fall of the Roman Empire. Thus, it is commonly held that all of Europe was, until recently, quite smelly indeed. Some hold the view that this is still the case.

There were serious exceptions, of course. I cannot resist mentioning a particularly well taken example, reported by the prior of St. Fridswides, John of Wallingford, “who complained bitterly that the Danes bathed once a week, combed their hair regularly, and changed their clothes regularly. The result was that English women were easily seduced by the nice-smelling Danes” (here).

A perhaps better-known example of European cleanliness is that of the Dutch. It is also the most seriously researched example. In the 17th and 18th century, visitors to Holland wondered about Dutch cleanliness, indeed, obsession with hygiene. Some have argued that this, somehow, reflected Dutch Calvinism. No, argue Bas van Bavel and Oscar Gelderblom in “The Economic Origins of Cleanliness in the Dutch Golden Age,” the reason is . . . butter! And here is the explanation (Abstract):

This paper explores why early modern Holland, and particularly its women, had an international reputation for cleanliness. We argue that economic factors were crucially important in shaping this habit. Between 1500 and 1800 numerous travellers reported on the habit housewives and maids had of meticulously cleaning the interior and exterior of their houses. We argue that it was the commercialization of dairy farming that led to improvements in household hygiene. In the fourteenth century peasants as well as urban dwellers began to produce large quantities of butter and cheese for the market. In their small production units women, and their daughters, worked to secure a clean environment for proper curdling and churning. We estimate that, at the turn of the sixteenth century, half of all rural households and up to one third of urban households in Holland produced butter and cheese. These numbers declined in the sixteenth century as peasants sold their land and larger farms were set up. Initially the migration of entire peasant families to towns, the hiring of farmers’ daughters as housemaids, and the exceptionally high consumption of dairy products continued to encourage the habit of regular cleaning in urban households. However, by the mid-seventeenth century the direct link between dairy farming and cleanliness was, for the most part, lost.

Quote of the Day: Bartley on the Marketplace of Ideas

| Peter Klein |

I happened to be looking today through Unfathomed Knowledge, Unmeasured Wealth by W. W. Bartley, III, who passed away shortly after this book was published. Bartley, a student and colleague of Karl Popper and the Founding Editor of The Collected Works of F. A. Hayek, was a brilliant and penetrating thinker whose work is not very well known outside of a few professional circles. Unfathomed Knowledge, a book about higher education (with the subtitle “On Universities and the Wealth of Nations”), was written for a general audience and is full of insights about the crazy business of academia. Here’s one passage:

Analogies have often been drawn between a free market in ideas and free markets in goods and services. Yet intellectuals tend to dislike such comparisons. They see the free market in ideas as something on a higher plane, qualitatively different from free markets in commodities and the like. Many of them indeed even hate the marketplace as traditionally conceived, and would want nothing to do, even analogically, with a free market in coal, housing, fish, or petroleum.

Take a few examples. Several scholars, including Edward Shils, of the University of Chicago, strongly protested the analogy when it was drawn by Michael Polanyi at the Congress for Cultural Freedom. One called Polanyi’s comparison between free markets in goods and in ideas “clever but questionable” in that a man who offers commodities in the free market “is not bound by anything” whereas in science one is bound to an objective method. Shils added that members of the scientific community, by contrast to businessmen and traders, act in accordance with overriding standards, a “common law” above and beyond individuals.

Such a position does not withstand examination. Someone offering commodities in a market — far from being “not bound by anything” — is governed by enforceable law relating to fraud, credit, contract and such like. The analogy does have limits, but of a different sort: in the marketplace of ideas, fraud, plagiarism, theft, false advertising (including false claims to expertise and the whole mystique of expertise), “conspiracies of silence,” casual slander and libel, breach of contract, deceit of all sorts are more common than in business — simply because there are few readily enforceable penalties against offenders, whereas “whistle-blowers” are severely punished. This is so especially in those areas (the humanities, social sciences, the arts — as opposed to the profitable fields) where the transaction costs of enforcing such things as property rights, priority claims, or even accurate report5ing usually outweigh the advantage in doing so, and where the transaction costs of trying to defend oneself against such things as slander are prohibitive.

Industry-Level Effects of Government Spending

| Peter Klein |

A consistent theme of this blog’s postings on the financial crisis and recession is that the Keynesians focus on too high a level of aggregation. As economists and management scholars we care primarily about industries, firms, and individuals, not abstract macroeconomic aggregates like GDP, the “price level,” etc. Heterogeneity matters, and the way stimulus programs affect the allocation of resources across firms and industries is as important, or more important, than their economy-wide effects.

A new NBER paper by Christopher Nekarda and Valerie Ramey uses disaggregated industry-level data to examine the effect of the current US stimulus program on output, employment, real wages, and productivity. They find, not surprisingly, that increases in government spending directed toward a specific industry raise that industry’s short-term output and employment but — contrary to New Keynesian predictions — reduce that industry’s real wages and productivity.

Nekarda and Ramey note that stimulus spending has been directed disproportionately to durable-goods manufacturing and that these industries have higher returns to scale than other industries, possibly explaining how reductions in industry-level productivity could look like productivity gains in the aggregate. In other words, stimulus spending reduces efficiency in all industries, but directs resources toward industries that were more efficient to begin with, giving the appearance of a positive aggregate effect. Thoughtful and provocative.

The Capitalist Kibbutz

| Peter Klein|

That’s how the Financial Times headlines this fascinating story about the transformation of many Israeli kibbutzim into partially privatized, profit-seeking, professionally managed entities that act in capital, product, and factor markets just like private firms. There are some similarities with the end of the socialist experiment in Russia: “‘The kibbutz was never isolated from society,’ says Shlomo Getz, the director of the Institute for Research of the Kibbutz at Haifa University. ‘There was a change in values in Israel, and a change in the standard of living. Many kibbutzniks now wanted to have the same things as their friends outside the kibbutz.”

The bottom line, from economist and former kibbutznik Omer Moav: “People respond to incentives. We are happy to work hard for our own quality of life, we like our independence. It is all about human nature — and a socialist system like the kibbutz does not fit human nature.” (Via BK Marcus.)

Brad’s Bloviations, Part #2,235

| Peter Klein |

Brad DeLong accuses non-Keynesians (Austrians, Chicagoites, and other sensible people) of “los[ing] themselves amidst their early-nineteenth century books, one hundred and seventy years behind the state of the art in economics,” just because they think public spending and deficits might be crowding out private-market activity, making it difficult — impossible, actually — to come up with meaningful estimates of “jobs saved” by stimulus spending. If you can get past Brad’s adolescent writing style (anyone citing Bastiat, for example, is “a truly clueless idiot”), you find that he is indeed very “progressive” in his thinking — he’s made it all the way to 1950. Brad, like most Keynesians, is stuck in the C + I + G world of undergraduate macro. His argument is that the stimulus can’t be crowding out private-sector jobs because (a) wages aren’t rising (implying that stimulus-funded workers aren’t being bid away from other potential opportunities) and (b) T-bill prices aren’t falling (suggesting that private employers aren’t competing with the Feds for credit).

Leave aside for the moment that Brad has no idea what wages and bond prices would be in the absence of stimulus. The key problem with Brad’s argument, noted by Russ Roberts, is its reliance on crude macroeconomic aggregates. As pointed out here many times, heterogeneity matters. Sensible economists care not about the aggregate unemployment rate, but the effect of stimulus activity on individual labor markets. Stimulus affects the composition of employment, not just its level. (more…)

Apocalypse Averted

| Dick Langlois |

In a recent post, I lamented the willingness of pundits (and dissenting Justices) to see rights as a consequential exercise: we should restrict the speech of group X, in this case private corporations, because allowing such speech would lead to a bad outcome, in this case the corruption of democracy by corporate interests. (Feel free to substitute here your own favorite candidate for silencing and your own associated bad outcome.) But, of course, those who argue in this manner must also demonstrate that the asserted bad outcome would actually happen. A recent article in the Times — bless some reporter’s or editor’s contrarian heart — asks the question: so, what effect does corporate money actually have on democracy?” The answer seems to be: none at all. One of the economists cited is Peter’s Missouri colleague, and my former student, Jeff Milyo: “There is just no good evidence that campaign finance laws have any effect on actual corruption.”

And while we are at it, a study by the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety finds no effect of cell phone laws on traffic accidents. This hasn’t stopped Connecticut’s Governor from calling for even stricter cell phone laws.

The Era of Laissez-Faire?

| Peter Klein |

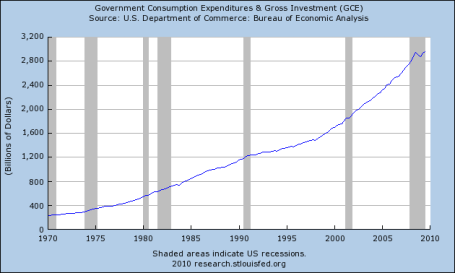

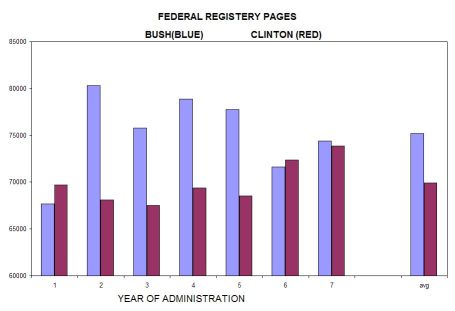

One of the established memes about the financial crisis is that it demonstrates the failure of unfettered capitalism, the dog-eat-dog, laissez-faire environment that prevailed in the West over the last few decades, all driven by the ideology of “free-market fundamentalism.” This seems to be a truism among most of the Commentariat. Of course, as pointed out repeatedly on this blog, the truth is virtually the opposite: there was never any “deregulation,” the Bush Administration spent public money like a drunken sailor, and government continued to expand as it always does. But a picture is worth a thousand words, so try these on for size. (US data; click charts for sources.)

One response I sometimes hear is “Sure, there are more regulations and more government spending, but the set of things that should be regulated and the amount of government spending the economy needs are growing even faster!” This is essentially the Krugman-DeLong view about the stimulus: it just wasn’t big enough. Or they say that financial markets were “deregulated,” de facto, because the number of regulations and regulators increased more slowly than the number of new financial instruments and new markets. I wonder, though: are these falsifiable propositions? No matter how big the government is, if there are any problems, it’s always because the government isn’t big enough!

Recent Comments