Posts filed under ‘Myths and Realities’

Recession and Recovery: Six Fundamental Errors of the Current Orthodoxy

| Peter Klein |

A very good summary by Bob Higgs of “vulgar Keynesianism,” defined by Bob as the “pseudointellectual mishmash . . . that has passed for economic wisdom in this country for more than fifty years.” The key feature of VK is an emphasis on crude aggregates (“national income,” “the employment rate,” “the interest rate,” etc.) at the expense of relative prices, firm and industry effects, and cause and effect. Echoing one of this blog’s favorite themes, Bob highlights the VK economist’s inability to grasp the concept of capital structure, “the fine-grained patterns of specialization and interrelation among the countless specific forms of capital goods in which past saving and investment have become embodied. In [the VK] framework of analysis, it matters not whether firms invest in new telephones or new hydroelectric dams: capital is capital is capital.”

Update: See also David Henderson on aggregation.

Words of Wisdom from Williamson’s Banquet Speech

| Peter Klein |

The transcript is here. My favorite bit, which can be read as a response to the econ-bashers:

Being hard-headed means that we aspire to tell it like it is — be it good news or bad. Although we take no joy in the downside, it is our duty candidly to confront all circumstances whatsoever. Our abiding concern is with improving the condition of mankind. Myopia, denial, and obfuscation are the enemy.

Only as we admit to and, of even greater importance, come to understand the problems that confront us — be they current or impending, obvious or obscure, real or imagined — by identifying and explicating the mechanisms that are responsible for these problems, can we expect to make informed decisions. Since, moreover, things that we do not understand at the outset sometimes have redeeming purposes, such efforts to get at the essence will often uncover real or latent benefits. Altogether, our capacity to work in the service of mankind increases as complex contract and economic and political organization become more susceptible to analysis.

Tuesday’s Prize lecture, in case you missed my earlier link, is here. I don’t see a video of the banquet speech on the Nobel site, but maybe that’s coming later. (Thank goodness they found time to post the seating chart!)

One tiny nit-pick: Williamson quotes Carlyle’s famous “dismal science” line, implicitly equating “dismal” with “mean-spirited,” but of course Carlyle’s barb had nothing to do with Malthus or scarcity or trade-offs, but with the classical economists’ opposition to slavery, which Carlyle, Dickens, Ruskin, and other literary critics of capitalism strongly supported (1, 2).

Boeing and the Higgs Effect

| Peter Klein |

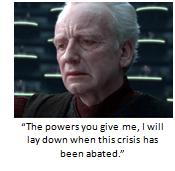

In their calls for greatly expanding the Federal Reserve System’s and Treasury Department’s roles in the economy, Chairman Bernanke, Secretaries Paulson and Geithner, and their academic enablers have repeatedly emphasized the temporary nature of these “emergency” measures. “History is full of examples in which the policy responses to financial crises have been slow and inadequate, often resulting ultimately in greater economic damage and increased fiscal costs. In this episode, by contrast, policymakers in the United States and around the globe responded with speed and force to arrest a rapidly deteriorating and dangerous situation,” said Bernanke in September. Yeah, no kidding. But, we are assured, the basic structure of our “free-enterprise” system remains soundly in place.

However, as Bob Higgs has taught us, “temporary,” “emergency” government measures are never that. Indeed, virtually all the major, permanent expansions of US government in the twentieth-century resulted from supposedly temporary measures adapted during war, recession, or some other “crisis,” real or imaginary. Cousin Naomi’s “disaster capitalism” thesis is exactly backward: it is socialism, or interventionism, that thrives during the crisis, and Washington, DC never looks back. I mean, does anyone seriously believe that the Fed will deny, or give back, the authority to purchase whatever financial assets it wishes at some future date when it deems the crisis officially “over”? Will the Treasury credibly commit never again to purchase equity or guarantee debt or otherwise protect some major industrial or financial firm after the economy returns to “normal”? Not a chance. Everything the authorities have done in the last two years to deal with this “emergency” will become part of the federal government’s permanent tool kit.

However, as Bob Higgs has taught us, “temporary,” “emergency” government measures are never that. Indeed, virtually all the major, permanent expansions of US government in the twentieth-century resulted from supposedly temporary measures adapted during war, recession, or some other “crisis,” real or imaginary. Cousin Naomi’s “disaster capitalism” thesis is exactly backward: it is socialism, or interventionism, that thrives during the crisis, and Washington, DC never looks back. I mean, does anyone seriously believe that the Fed will deny, or give back, the authority to purchase whatever financial assets it wishes at some future date when it deems the crisis officially “over”? Will the Treasury credibly commit never again to purchase equity or guarantee debt or otherwise protect some major industrial or financial firm after the economy returns to “normal”? Not a chance. Everything the authorities have done in the last two years to deal with this “emergency” will become part of the federal government’s permanent tool kit.

Today’s WSJ has a good example of Higgs’s ratchet effect, a front-pager on Boeing’s dependence on export loan guarantees from the Export-Import Bank, a federal government agency created in — you guessed it — 1934, as a temporary agency to deal with the Great Depression. “No company has deeper relations with Ex-Im Bank than Chicago-based Boeing. Without Ex-Im, aviation officials say, Boeing this year could have been forced to slash production, endangering hundreds of U.S. suppliers, thousands of skilled American jobs and billions of dollars in export contracts.” Bank official Bob Morin is described as “Ex-Im Bank’s rainmaker. His Boeing deals accounted for almost 40% of the bank’s $21 billion in business last year. To help Boeing through the credit crunch, his team has spent the past year developing government-backed bonds that promise to raise billions.” So, a massive industrial-planning apparatus, supposedly born during a temporary crisis, lives on as the lifeblood of a huge, politically connected US company.

Thank goodness all that money flowing to Goldman Sachs is only temporary!

Update: Here’s a short Higgs piece from 2000 on the Ex-Im Bank, appropriately titled “Unmitigated Mercantilism.”

The WSJ on Vertical Integration

| Peter Klein |

It’s not as bad as this 2006 piece from Slate, but Monday’s WSJ front-pager, “Companies More Prone to Go ‘Vertical,'” is underwhelming at best. It shares a few interesting anecdotes about recent vertical mergers, but falls flat on two major grounds. First, like the Slate piece, it assumes that the advances in IT over the last few decades led to some sort of tectonic shift away from vertical integration, against which firms are now reacting by “rediscovering” the benefits of vertical coordination. Actually there’s little evidence for such a shift. Second, and more important, the article doesn’t bother to mention any theories about what vertical integration is and does. There are vague references to commodity-price volatility and the need to “control” the supply chain, but no recognition that risk-management and control over inputs can be achieved through contract as well as integration. Given that one of this year’s Nobel Laureates won the prize for his work on precisely this problem, you’d think some reference to transaction costs might be appropriate. Old Media, R.I.P.

important, the article doesn’t bother to mention any theories about what vertical integration is and does. There are vague references to commodity-price volatility and the need to “control” the supply chain, but no recognition that risk-management and control over inputs can be achieved through contract as well as integration. Given that one of this year’s Nobel Laureates won the prize for his work on precisely this problem, you’d think some reference to transaction costs might be appropriate. Old Media, R.I.P.

Nirvana Fallacy Alert, #2,535 in a Series

| Peter Klein |

Another mistake in John Cassidy’s ditty on externalities is the claim that Pigou “was reacting against laissez faire — the hands-off approach to policy that free market economists, from Adam Smith onwards, had recommended. Such thinkers had tended to view the market economy as a perfectly balanced, self-regulating machine.” Forget that the British Classicals, Adam Smith in particular, were far from “hands-off” types. Note instead that Cassidy provides no textual evidence of unnamed “free-market economists” viewing the market system as a “perfectly balanced, self-regulating machine.” How could he, when no sensible economist ever wrote or thought such a thing? The free-market economists — actually, virtually all sound economists — have maintained that the market economy works remarkably well, given the limits of human knowledge, our devious character, the brutality of nature, and so on. Paris gets fed, as Bastiat noted, and that is a miracle. Government intervention into markets inevitably makes things worse, the economists argued, not because the market system is “perfect,” whatever that means, but because men are fallible, and giving coercive power to fallible men is — to borrow P. J. O’Rourke’s metaphor — like giving whiskey and car keys to teenage boys. Cassidy’s caricature shows how little he understands what free-market economics is actually all about.

Modest, Slow, Molecular, Definitive

| Peter Klein |

In an oft-cited passage from The Mechanisms of Governance (1996), Williamson describes the research program of transaction cost economics this way:

Transaction cost economics (1) eschews intuitive notions of complexity and asks what the dimensions are on which transactions differ that present differential hazards. It further (2) asks what the attributes are on which governance structures differ that have hazard mitigation consequences. And it (3) asks what main purposes are served by economic organization. Because, moreover, contracting takes place over time, transaction cost economics (4) inquires into the intertemporal transformations that contracts and organization undergo. Also, in order to establish better why governance structures differ in discrete structural ways, it (5) asks why one form of organization (e.g., hierarchy) is unable to replicate the mechanisms found to be efficacious in another (e.g., the market). The object is to implement this microanalytic program, this interdisciplinary joinder of law, economics, and organization, in a “modest, slow, molecular, definitive” way.

A footnote explains the origins of the phrase “modest, slow, molecular, definitive,” tracing them to a (secondhand) quotation from Charles Péguy. Here’s the footnote:

The full quotation (source unknown) reads:

“The longer I live, citizen. . .” — this is the way the great passage in Peguy begins, words I once loved to say (I had them almost memorized) — “The longer I live, citizen, the less I believe in the efficiency of sudden illuminations that are not accompanied or supported by serious work, the less I believe in the efficiency of conversion, extraordinary, sudden and serious, in the efficiency of sudden passions, and the more I believe in the efficiency of modest, slow, molecular, definitive work. The longer I ive the less I believe in the efficiency of an extraordinary sudden social revolution, improvised, marvelous, with or without guns and impersonal dictatorship — and the more I believe in the efficiency of modest, slow, molecular, definitive work.”

Well, we are nothing if not pedantic here at O&M, and in that spirit, I share (with permission) a note from my colleague and former guest blogger Randy Westgren, written to Williamson in January 2007, explaining that the anonymous source has botched the Péguy quotation. Here’s Randy:

After a long search, I found the quote from Péguy that you cite in footnote nine of the Prologue of The Mechanisms of Governance and noted again in footnote eleven of the first chapter. I was not able to find the secondary quote that is printed in the footnote, but I did find the original passage from Péguy. I have been searching for this since The Mechanisms was published, because I could not fathom how Charles Péguy could have denounced sudden, wondrous conversion and sudden, extraordinary social revolution when he was (1) a famously devout Catholic; a mystic whose poetry includes an exceptional hommage to Joan of Arc, and (2) a famously ardent socialist who believed strongly in the overthrow of the bourgeoisie. In fact, after giving up on the Catholicism of his youth while at the École Normale Supérieure, he returned to his faith in the middle of the first decade of the century, when he was in his early 30s. He was slain in the first battle of the Marne in 1914 at the age of 41. (more…)

The Igon Value of Cognitive Dissonance

| Dick Langlois |

Some of you may have seen Steven Pinker’s review of Malcolm Gladwell’s latest book in the New York Times this weekend. Pinker praises Gladwell’s writing and his instinct for interesting topics, but skewers him for his bad grasp of the underlying science of what he writes about, especially statistics. In Pinker’s view, Gladwell is in the end a character from one of his own essays, “a minor genius who unwittingly demonstrates the hazards of statistical reasoning and who occasionally blunders into spectacular failures.” One blunder seems to epitomize Pinker’s assessment: Gladwell’s report on an expert who talks of “igon values” instead of eigenvalues. Pinker call this the igon value effect.

As I read this, I thought back to a department seminar I had attended a couple of days earlier. Keith Chen from Yale gave one of the most dazzling presentations I’ve heard in a long time. He basically demolished 45 years of experimental results in social psychology that claim to have discovered cognitive dissonance in choices. According to this literature, it is among the best-documented results in psychology that people change their preferences after making a choice so as to rationalize the choice and make themselves feel better about their decision. Chen argues — persuasively — that essentially all these results are statistical artifacts. At a much more sophisticated level, social psychologists have fallen victim to the igon value effect. Here is the abstract of a working paper, though it gives only a hint of how clever this research is.

Cognitive dissonance is one of the most influential theories in social psychology, and its oldest experiential realization is choice-induced dissonance. Since 1956, dissonance theorists have claimed that people rationalize past choices by devaluing rejected alternatives and upgrading chosen ones, an effect known as the spreading of preferences. Here, I show that every study which has tested this suffers from a fundamental methodological flaw. Specifically, these studies (and the free-choice methodology they employ) implicitly assume that before choices are made, a subject’s preferences can be measured perfectly, i.e. with infinite precision, and under-appreciate that a subject’s choices reflect their preferences. Because of this, existing methods will mistakenly identify cognitive dissonance when there is none. This problem survives all controls present in the literature, including control groups, high and low dissonance conditions, and comparisons of dissonance across cultures or affirmation levels. The bias this problem produces can be fixed, and correctly interpreted several prominent studies actually reject the presence of choice-induced dissonance in their subjects. This suggests that mere choice may not be enough to induce rationalization, a reversal that may significantly change the way we think about cognitive dissonance as a whole.

Chen was also written up in the New York Times last year.

Oh, and by the way, that was our second seminar of the day. Earlier we listened to Bob Lucas, whom the grad students brought in to give a major lecture. (First time I had met him.) He talked about his paper in the inaugural issue of the new AEA macro journal: “Trade and the Diffusion of the Industrial Revolution.” (There wasn’t actually much trade in it.) Lucas and I had a nice conversation at lunch about Jane Jacobs, who we agreed was fantastic. “She was a theorist!” was Lucas’s assessment. High praise.

Keynesian Anti-Economics

A reader objected to my recent portrayal of Keynes as a crank, as a man who never really studied economics or took it very seriously. Note that I never denied Keynes’s intellect, his great skill as a rhetorician, or his personal charm. But Keynesian economics is, in a sense, non-economics or even anti-economics, in that it ignores or contradicts many basic lessons about the allocation of scarce resources among competing ends. Mario Rizzo feels the same way:

Keynesianism is not concerned with the allocation of resources and related niceties. One can see this is the policy prescriptions of the stimulators. Just get people back to work. If a market is depressed: Prop it up. Labor, other resource-owners and entrepreneurs need to stop worrying about searching for the appropriate use of resources. Bankers have to stop fretting about to whom they should lend. They should abandon their ultra-restraint. Those who are holding money should invest; they should buy bonds. No need to worry about inflation because the potential output of “stuff” (however it is allocated across industries) is above the actual less-than-full-employment output.

Where did my microeconomics go?

Keynes and his followers proudly trumpeted his framework as a re-do of standard economics (what he called “classical,” though Keynes was not well versed in the history of economic thought). Standard economics is OK during periods of “full employment” (another aggregate concept, of course), but not in the “general” case, in which case the Keynesian magic comes into play. Credit expansion, according to Keynes, performs the “miracle . . . of turning a stone into bread.” As Mises noted, “Great Britain has indeed traveled a long way to this statement from Hume’s and Mill’s views on miracles.”

The Amazing Krugman

| Peter Klein |

The man indeed has a unique talent, as described here by the witty and clever Steve Landsburg:

It’s always impressive to see one person excel in two widely disparate activities: a first-rate mathematician who’s also a world class mountaineer, or a titan of industry who conducts symphony orchestras on the side. But sometimes I think Paul Krugman is out to top them all, by excelling in two activities that are not just disparate but diametrically opposed: economics (for which he was awarded a well-deserved Nobel Prize) and obliviousness to the lessons of economics (for which he’s been awarded a column at the New York Times).

It’s a dazzling performance. Time after time, Krugman leaves me wide-eyed with wonder at how much economics he has to forget to write those columns.

The subject is Krugman’s latest proposal to combat unemployment, namely laws making it harder to fire workers, which of course increases the cost of labor, leading firms to hire less of it, increasing unemployment.

Fed Independence and Comparative Institutional Analysis

| Peter Klein |

I’ve written before on Fed “independence” and why I don’t support it. The vast majority of economists, especially the more prominent ones, are strongly in favor of independence and against Congressional attempts to limit the Fed’s discretion in monetary and regulatory policy. The standard argument is that a “politicized” — i.e., accountable — central bank will be more expansionary than an unaccountable central bank, assuming that credit expansion affects output first and prices (inflation) second. Last week’s piece by Kashyap and Mishkin follows this script. On the face of it, this seems absurd, as — to take only the most obvious example — the Greenspan-Bernanke “independent” Fed has been the most expansionist in modern history, with a ballooning money supply throughout the 2000s and near-zero interest rates and injections of giggledysquillions of dollars into the banking sector in the last 18 months. The independence crowd cites cross-country studies finding a negative correlation between central-bank independence and inflation, but these studies are controversial (many problems with reverse causation, omitted variables, sample size, etc.).

My question today is different: Where, in those arguments, is the comparative institutional analysis? After all, in policy analysis, we are always comparing imperfect alternatives. We try to avoid the Nirvana fallacy. Craig does this in his post below, asking if a centralized financial regulator would be less bad than the competing regulatory bodies we have today.

But the macroeconomists entirely ignore this problem. Consider Mark Thoma’s defense of independence:

The hope is that an independent Fed can overcome the temptation to use monetary policy to influence elections, and also overcome the temptation to monetize the debt, and that it will do what’s best for the economy in the long-run rather than adopting the policy that maximizes the chances of politicians being reelected.

This naive wish is simply that, a hope. Where is the argument or evidence that a wholly unaccountable Fed would, in fact, “do what’s best for the economy in the long-run”? What are the Fed officials’ incentives to do that? What monitoring and governance mechanisms assure that Fed officials will pursue the public interest? What if they have private interests? Maybe they’re motivated by ideology. Suppose they make systematic errors. Maybe they’ve been captured by special-interest groups like, oh, I don’t know, the banking industry (duh). To make a case for independence, it is not enough to demonstrate the potential hazards of political oversight. You have to show that these hazards exceed the hazards of an unaccountable, unrestricted, ungoverned central bank. The mainstream economists totally ignore this question, choosing to put a naive faith in the wisdom of central bankers to do what’s right. Guys, have you never heard of public-choice theory?

No Required Ethics Course at Chicago-Booth

| Peter Klein |

Bucking the trend, the Chicago-Booth MBA program will not offer required courses in business ethics (via Cliff). The school “has no set standard for ethical case studies used in the classroom,” according to Executive Director of Faculty Services Lisa Messaglia,”but leaves it up to faculty, instead.”

[T]he business school is disciplined-based, meaning that classes are divided by disciplines such as sociology or psychology, rather than by industries. As a result, she said, professors may use different examples in their lectures, but Chicago Booth “[doesn’t] change required classes based on trends in the economy.”

I’m not keen on the way ethics is taught in most business schools so I’m sympathetic to the Chicago position. Some previous O&M posts on teaching ethics are here, here, here, here, here, and here.

The Hodgson Petition

| Peter Klein |

Several friends and colleagues urged me to sign Geoff Hodgson’s petition on the financial crisis, but I declined. I agree with Krugman that economists have tended to mistake mathematical beauty for truth, but think this has little to do with the financial crisis. As discussed in previous posts, I view the financial crisis and recession as the (predicable!) result of government failure — massive credit expansion by the central bank, mortgage-lending rules and policies designed to inflate the housing market, a state-sponsored cartel of securities-rating agencies — not market failure resulting from unrealistic behavioral assumptions.

I respect many of the signatories to the petition, but statements like this (from Krugman), at the heart of the petition, are preposterous:

[Economists] turned a blind eye to the limitations of human rationality that often lead to bubbles and busts; to the problems of institutions that run amok; to the imperfections of markets — especially financial markets — that can cause the economy’s operating system to undergo sudden, unpredictable crashes; and to the dangers created when regulators don’t believe in regulation. . . . When it comes to the all-too-human problem of recessions and depressions, economists need to abandon the neat but wrong solution of assuming that everyone is rational and markets work perfectly.

“Regulators who don’t believe in regulation?” Paul, what color is the sky on your planet (1, 2, 3)? Notably absent from the petition’s list of villains is the Fed, Fannie and Freddie, the Treasury, or indeed anyone remotely connected with a government body.

Keep in mind it was Krugman himself who wrote in 2002: “To fight this recession the Fed needs more than a snapback; it needs soaring household spending to offset moribund business investment. And to do that . . . Greenspan needs to create a housing bubble to replace the Nasdaq bubble.” St. Alan followed Krugman’s advice to the letter, and here we are today.

QWERTY in the Long Run

| Dick Langlois |

The new issue of Industrial and Corporate Change has an article by Andreas Reinstaller and Werner Hölzl called “Big Causes and Small Events: QWERTY and the Mechanization of Office Work.” Although it’s an interesting paper in many respects, I think it fails in its avowed aim to defend Paul David against the attack of Liebowitz and Margolis. Mostly, they don’t get L&M right (and explicitly get them wrong in footnote 1). The issue is whether the QWERTY keyboard is an example of what L&M call “third-degree” path dependency, that, is path dependency leading to an outcome that is both regrettable ex post and would somehow have been remediable ex ante. The criterion of “remediable” to R&H seems to be whether contemporaries “knew about” superior alternatives. That’s not quite right, of course: the real issue is whether any alternative institutional structure could have done a better job of choosing a standard under the conditions of knowledge at the time. Their only example is the existence of a French “Ideal” keyboard layout (which some people “knew about”) that was swept aside by the tidal wave of the American QWERTY standard (and became AZERTY in France). But they have no evidence about how much better this keyboard was — or if it was better at all. In footnote 1 they cite Donald Norman’s interesting book on design to the effect that the Dvorak keyboard is 10 per cent faster than QWERTY. But (A) Norman’s point in the book is how insignificant this difference is and (B) that doesn’t demonstrate third-degree path dependency, since no one “knew about” the Dvorak keyboard until Dvorak invented it (an extremely laborious process, according to Norman).

Again, I don’t want to be too hard on R&H: I think there’s a lot that’s interesting in the paper, especially the discussion of the mechanization of office work. What really struck me in this context, however, is how irrelevant, or at least dated, the QWERTY saga is. And I say this not for the usual reason: that computers now allow us to have any keyboard layout we like. Rather, what struck me is that the production of documents has long since become demechanized, making even more-than-nominal differences in typing speed irrelevant. Since we now all (or almost all) compose right on the computer, and never send our documents out to the typing pool, manuscript production has become a craft again. What is slowing us down is how quickly we think of something to say, not how fast we can type. And I doubt that, fifties nostalgia notwithstanding, we are unlikely to see the return of the typing pool anytime soon. So, from a historical perspective, QWERTY will have been technically inefficient (though not therefore economically inefficient) only for that brief historical period between the invention of Dvorak and the coming of the personal computer.

The same issue of ICC also has a paper by Ashish Arora and coauthors that’s worth a look.

Famous Misquotes

| Peter Klein |

What are your favorite famous misquotes in social science? E.g., everybody knows Lord Acton’s dictum: “Power corrupts, and absolute power corrupts absolutely.” Except he actually wrote “power tends to corrupt, and absolute power corrupts absolutely.” Likewise, Adam Smith didn’t say that the merchant is led “as if by an invisible hand” to promote an end not his intention; he said the merchant “is in this, as in many other cases, led by an invisible hand. . . .” And, to get to the really deep thinkers, Gordon Gekko didn’t say “greed is good,” but “greed, for lack of a better word, is good. Greed is right. Greed works. Greed clarifies, cuts through and captures the essence of the evolutionary spirit. . . .” I love you, man!

On a related note, David Levy and Sandra Peart explain that Thomas Carlyle’s description of economics as the “dismal science” had nothing to do with Malthusian overpopulation. Carlyle actually despised the economists because they supported the emancipation of slaves and believed, in Levy and Peart’s words, “it was institutions, not race, that explained why some nations were rich and others poor.”

Climate Change Economics

| Glenn MacDonald |

Some thoughts about how carbon emissions will evolve. Assume carbon emissions cause climate change. (Obviously this is controversial. But I have nothing new to add to this and so am willing to grant this assumption.) There are two fundamental economic forces at work. One is that emissions are a classical prisoners’ dilemma. That is, reducing emissions is costly, and the benefits to any one country are mainly enjoyed by others. Thus, in equilibrium, there will not be a lot of effort devoted to reducing emissions. Getting around this would require either some sort of external enforcement, e.g., the United Nations (pause for laughter!), or some approach based on repeated interaction; unfortunately the latter requires more patience and information than is realistic in this situation. Thus, consistent with the data, emissions will grow, and, per my assumption, climate change will ensue. Second, tastes for amenities such as clean air appear to be normal goods, maybe even luxuries. Individuals in China, eastern Europe, . . . appear to have little interest in these amenities, given what they might have to forego to have them, whereas many in the US, Canada, western Europe, . . . seem more inclined to pay a little more for green goods and services. Thus, efforts to reduce emissions will grow as more and more countries prosper sufficiently that their inhabitants are willing to forgo consumption for cleaner air, etc. So, from an economic perspective, the most realistic way to fewer carbon emissions and (per my assumption) less climate effects is through the aggressive promotion of activities that promote growth: free trade, democracy, economic freedom, reduced taxes, regulations and tariffs, protection of property rights. . . . Interestingly, freeing individuals to pursue their interests is likely the best practical/realitic approach to what, at first blush, seems like a classical case for collective action.

Two Quotations on Profits

| Peter Klein |

Henry Hazlitt, from Economics in One Lesson:

In a free economy, in which wages, costs and prices are left to the free play of the competitive market, the prospect of profits decides what articles will be made, and in what quantities — and what articles will not be made at all. If there is no profit in making an article, it is a sign that the labor and capital devoted to its production are misdirected: the value of the resources that must be used up in making the article is greater than the value of the article itself.

One function of profits, in brief, is to guide and channel the factors of production so as to apportion the relative output of thousands of different commodities in accordance with demand. No bureaucrat, no matter how brilliant, can solve this problem arbitrarily. Free prices and free profits will maximize production and relieve shortages quicker than any other system. Arbitrarily fixed prices and arbitrarily limited profits can only prolong shortages and reduce production and employment.

The function of profits, finally, is to put constant and unremitting pressure on the head of every competitive business to introduce further economies and efficiencies, no matter to what stage these may already have been brought.

Barack Obama, from last week’s address on healthcare:

I’ve insisted that like any private insurance company, the public insurance option would have to be self-sufficient and rely on the premiums it collects. But by avoiding some of the overhead that gets eaten up at private companies by profits and excessive administrative costs and executive salaries, it could provide a good deal for consumers, and would also keep pressure on private insurers to keep their policies affordable and treat their customers better. . . .

So, (a) profits and executive salaries are part of (avoidable) overhead, and (b) government agencies have lower administrative costs than private firms. Who knew? (Thanks to Gary for the quote.)

Not Even the Slightest Soupçon of Correlation

| Dick Langlois |

Another interesting article from the Journal of Wine Economics:

The lead article is again by Robert T. Hodgson, who analyzes the reliability of Gold medals awarded at 13 California Wine Fairs. “An analysis of over 4000 wines entered in 13 U.S. wine competitions shows little concordance among the venues in awarding Gold medals. Of the 2,440 wines entered in more than three competitions, 47 percent received Gold medals, but 84 percent of these same wines also received no award in another competition. Thus, many wines that are viewed as extraordinarily good at some competitions are viewed as below average at others. An analysis of the number of Gold medals received in multiple competitions indicates that the probability of winning a Gold medal at one competition is stochastically independent of the probability of receiving a Gold at another competition, indicating that winning a Gold medal is greatly influenced by chance alone.” The full article can be accessed free of charge at Abstract Full Text (PDF).

The Pretense of Bernanke’s Knowledge

| Peter Klein |

Chairman Bernanke, in his own words:

July 2005: “[U]nquestionably, housing prices are up quite a bit; I think it’s important to note that fundamentals are also very strong. We’ve got a growing economy, jobs, incomes. We’ve got very low mortgage rates. We’ve got demographics supporting housing growth. We’ve got restricted supply in some places. So it’s certainly understandable that prices would go up some. I don’t know whether prices are exactly where they should be, but I think it’s fair to say that much of what’s happened is supported by the strength of the economy.”

July 2005: “[Recession is] a pretty unlikely possibility. We’ve never had a decline in house prices on a nationwide basis. So what I think is more likely is that house prices will slow, maybe stabilize: might slow consumption spending a bit. I don’t think it’s going to drive the economy too far from its full employment path, though.”

February 2007: “Our assessment is that there’s not much indication at this point that subprime mortgage issues have spread into the broader mortgage market, which still seems to be healthy. And the lending side of that still seems to be healthy.”

July 2007: “The pace of home sales seems likely to remain sluggish for a time, partly as a result of some tightening in lending standards, and the recent increase in mortgage interest rates. Sales should ultimately be supported by growth in income and employment, as well as by mortgage rates that, despite the recent increase, remain fairly low relative to historical norms. . . . Overall, the U.S. economy seems likely to expand at a moderate pace over the second half of 2007, with growth then strengthening a bit in 2008 to a rate close to the economy’s underlying trend.”

July 2009: “Overall, the Federal Reserve has many effective tools to tighten monetary policy when the economic outlook requires us to do so. As my colleagues and I have stated, however, economic conditions are not likely to warrant tighter monetary policy for an extended period. We will calibrate the timing and pace of any future tightening, together with the mix of tools to best foster our dual objectives of maximum employment and price stability.”

What Does the Rule of Law Variable Measure?

| Peter Klein |

Bill Easterly poses this question, referring to his NYU colleague Kevin Davis’s work on law and development. Davis has several papers criticizing economists’ use of rule-of-law variables in development research (1, 2, 3). As summarized by Easterly:

Kevin points out that two current measures of “rule of law” used by economists in “institutions cause development” econometric research are by their own description a mixture of some characteristics of the legal system with a long list of non-legalistic factors such as “popular observance of the law,” “a very high crime rate or if the law is routinely ignored without effective sanction (for example, widespread illegal strikes),” “losses and costs of crime,” “corruption in banking,” “crime,” “theft and crime,” “crime and theft as obstacles to business,” “extent of tax evasion,” “costs of organized crime for business” and “kidnapping of foreigners.” Showing that this mishmash is correlated with achieving development tells you what exactly? Hire bodyguards for foreigners?

What if “institutions” are yet another item in the long list of panaceas offered by development economists that don’t actually help anyone develop?

Easterly opens with a clever example of a legal rule that doesn’t make sense outside an informal, non-rule context. But overall I think he’s a little unfair to the development and financial economists working in this area, many of whom are sensitive to these problems but are doing the best they can with the data available. It’s true, however, that much of the early work, particularly in the LLSV tradition, conflated de jure and de facto rules (particularly in over-emphasizing differences between common-law and civil-law countries). Benito Arruñada’s critique of the Doing Business Project is also informative in this regard.

Greif’s Response to Rowley

| Peter Klein |

Avner Greif has written a response to Charles Rowley’s odd claim that Greif “denied Janet Landa her full intellectual property rights with respect to her contributions to the economic analysis of trust and identity.” Public Choice, which published Rowley’s critique, will run the reply. Avner kindly sent me an advance copy and gave me permission to post it here. Full text below the jump.

My $0.02: This is a very effective reply, pointing out that Landa’s and Greif’s explanations for trust are quite different (one based on preferences, the other on beliefs). Avner, perhaps wisely, steers clear of the general epistemological problem: How do you know if scholar A has cited predecessor B “enough”? Expecting A to show he hasn’t unfairly neglected B is asking A to prove a negative. Ultimately, the whole exercise seems petty to me. B’s defenders should focus on elevating B’s reputation, not complaining about A, C, and D’s failure to show the love.

The Curious Commentary on the Citation Practices of Avner Greif

By Avner Greif

August 2009

Forthcoming at Public Choice

Abstract: Rowley (2009) failed, among other faults, to recognize the substantive distinction between the lines of research pursued by Professor Landa and myself. Its claim that I have “expropriated” (p. 276) intellectual property rights from Professor Landa by insufficiently citing her works is vacuous. (more…)

Recent Comments