Posts filed under ‘Myths and Realities’

Heterogeneity and Health Care

| Peter Klein |

Further to Russ’s post: One of the most frustrating aspects of the discussion surrounding health-care reform is the tendency of politicians, activists, and even a few economists to talk about “health care” as if it’s a homogeneous blob, or an intangible thing like “love” or “happiness.” Of course, what we produce and consume, what we exchange on markets, is not “health care” but specific, discrete health-care goods and services (procedures, medications, insurance policies, etc.). If you never go to the doctor and consume only one aspirin per year, do you have “health care”? If not, what specific bundle of goods and services constitutes a unit of “health care”?

Once we realize we are really talking about discrete, marginal units of particular goods and services the very notion of “universal access to health care” becomes problematic. What exactly is it that people have a universal right to? It’s analogous to debates about the environment. One can have a sort of philosophical or meta-economic commitment to “the environment,” and its protection (hoo-boy), but this means very little in terms of specific trade-offs at the margin. Is it better to have one more house or airport runway or corn field, or one more patch of meadow or forest? Being an “environmentalist” doesn’t answer that question. You know the old story: everybody values “safety,” but that doesn’t mean you never leave your house or, when you do, drive to work in a Sherman tank. You willingly sacrifice some amount of safety in exchange for units of other scarce and valuable goods (like access to the world outside your house, time spent traveling, money). Each of us evaluates this trade-off differently. Likewise, the marginal valuations of specific health-care goods and services, relative to other consumption and investment goods, cash balances, etc. varies from individual to individual. There’s no such thing as “health care.” As always, heterogeneity matters.

Federal Reserve “Independence”

| Peter Klein |

I was invited to sign the Open Letter in support of Fed independence but, like Jerry O’Driscoll, Bob Higgs, and Larry White, I don’t support the cause. Follow the links above for detailed arguments. For my part:

1. The Open Letter focuses exclusively on monetary policy, as if the Fed’s Congressional critics like Ron Paul just want to know how the Federal Funds Rate is set. But the Fed conducts not only monetary policy, but fiscal policy as well, especially during the last 18 months. If the Fed can buy and hold any assets it likes, if it works hand-in-hand with the White House and the Treasury to coordinate trillion-dollar bailouts, isn’t it reasonable to have some oversight? (And don’t forget bank supervision. Even the Fed’s defenders recognize a need to separate its monetary-policy and bank-supervision roles. But as long as the Fed continues as a bank regulator, shouldn’t someone should be watching the watchmen?)

2. The Open Letter itself is poorly crafted, full of unsubstantiated assertions and misleading statements. There’s no argument there, as Higgs emphasizes. Actually, neither the time-series or cross-sectional evidence suggests any correlation between central-bank independence (whatever that means) and economic performance.

3. More generally, the Fed is a central planning agency, and it performs about as well as every central planning agency in history. Have we learned nothing from the huge literature on comparative economic systems? “Independence,” in this context, simply means the absence of external constraint. There are no performance incentives and no monitoring or governance. There is no feedback or selection mechanism. There is no outside evaluation (outside the blogosphere). Why on earth would we expect an organization operating in that environment to improve social welfare? Is this institution run by men, or gods?

Department of They Just Don’t Get It

| Peter Klein |

Paul Ehrlich, author (with Anne Ehrlich) of The Population Bomb (1968), one of the biggest, um, bombs of the last several decades, is unrepentant. Ehrlich’s main thesis was that the world was running out of natural resources, and population growth was expanding exponentially, leading to an inevitable decline in living standards. Needless to say, none of the three predictions came true, and Bomb became one of those books that cultural anthropologists study for its train-wreck value. Now, apparently for laughs, the Electronic Journal of Sustainable Development has invited the Ehrlichs to write “The Population Bomb Revisited” for a forthcoming symposium. After all these years, the Ehrlichs are no closer to grasping the Econ 101 concept of “resources,” namely means used by human actors to achieve desired ends — not physical stocks of raw materials, but raw materials interacted with human knowledge and purpose. (more…)

Does Macroeconomic Theory Influence Macroeconomic Policy?

| Peter Klein |

Not really, according to John Wood’s History of Macroeconomic Policy in the United States (Routledge, 2008). As David Wheelock notes in his EH.Net review:

Wood argues that U.S. fiscal and monetary policy have been remarkably consistent over the decades and largely uninfluenced by macroeconomic theory. Economists have rationalized more than influenced policy, Wood contends, and the direction of influence between economic theory and practice is primarily from the latter to the former.

This is of course the classic explanation for the spread of Keynesianism after 1936: rather than proposing a new approach to macroeconomic policy, the General Theory simply rationalized the massive deficit-spending and easy-money policies already in place (and long desired by disreputable economists such as Foster and Catchings).

Does Capitalism Suffer Cycles of Statism?

| Benito Arruñada |

Does the current expansion of the State reverse a previous reduction, to be reduced once again in the future? Or, alternatively, is there a sort of ratchet effect, with a trend towards greater statism disguised by cycles along such increasing trend?

I am inclined to think that cycling has not taken place around a stationary average but around an increasing tendency (see the figures). But perhaps a better way of facing these questions would be to disaggregate in different dimensions. For instance, in several papers with Veneta Andonova we argue that freedom

I am inclined to think that cycling has not taken place around a stationary average but around an increasing tendency (see the figures). But perhaps a better way of facing these questions would be to disaggregate in different dimensions. For instance, in several papers with Veneta Andonova we argue that freedom  of contract has been in decline for more than a century in Western Law, both in civil- and common-law countries. Something similar could probably be said about trade, but in the opposite direction. However, in both freedom of contract and trade, it might be the case that exchange opportunities have expanded mainly as a result of technological change (e.g., cheaper transportation and communications), whatever the legal constraints. In terms of research, how could these trends be measured?

of contract has been in decline for more than a century in Western Law, both in civil- and common-law countries. Something similar could probably be said about trade, but in the opposite direction. However, in both freedom of contract and trade, it might be the case that exchange opportunities have expanded mainly as a result of technological change (e.g., cheaper transportation and communications), whatever the legal constraints. In terms of research, how could these trends be measured?

These thoughts were triggered by a timely and extremely suggestive paper by Witold J. Henisz presented at the Workshop on “Manufacturing Markets” organized last week in Villa Finaly, Florence, by Eric Brousseau and Jean-Michel Glachant. My next few blogs will address other aspects of Henisz’s views on the broader challenges facing capitalism.

The Hawthorne Effect Revisited

| Peter Klein |

The ever-resourceful Steve Levitt, working with John List, uncovers the original data from the Hawthorne experiments — data long thought to have been lost or destroyed — and finds there actually wasn’t much of a Hawthorne effect:

Our analysis of the newly found data reveals little evidence to support the existence of a Hawthorne effect as commonly described; i.e., there is no systematic evidence that productivity jumped whenever changes in lighting occurred. On the other hand, we do uncover some weak evidence consistent with more subtle manifestations of Hawthorne effects in the data. In particular, output tends to be higher when experimental manipulations are ongoing relative to when there is no experimentation. Also consistent with a Hawthorne effect is that productivity is more responsive to experimenter manipulations of light than naturally-occurring fluctuations. . . . We conclude that the evidence for a Hawthorne effect in the studies that gave the phenomenon its name is far more subtle than has been previously acknowledged.

The short paper, “Was there Really a Hawthorne Effect at the Hawthorne Plant? An Analysis of the Original Illumination Experiments,” is available from NBER. I couldn’t find an ungated copy but the search led me to a large secondary literature, much of it by organizational and industrial psychologists, also questioning the original findings, though apparently without use of the primary data.

Sociology that We Like

| Nicolai Foss |

Contrary to the conviction perhaps held by the boys over at orgtheory.net, O&M bloggers are not at all hostile to sociology. In fact, we are highly sympathetic to what is sometimes called “analytical sociological theory,” that is, James Coleman, Raymond Boudon, Jon Elster, Peter Abell, Diego Gambetta, Siegwart Lindenberg, Karl-Dieter Opp, and so on. Here is a nice summary of AST, which — we are told — embraces realism and objectivity, is anti-relativist, appreciates formalization and the use of models, is reductionist, eschews bullshit, etc. (Also check out the nice and entirely well taken acerbic treatment of Foucault on p. 7). Now we only need to know: How exactly does AST differ from microeconomics?

PAL Team on Microfinance

| Peter Klein |

As a microfinance skeptic I was particularly interested in the new paper from the J-PAL team of Banerjee, Duflo, Glennerster, and Kinnan, “The Miracle of Microfinance? Evidence from a Randomized Evaluation.” Despite the pedestrian abstract, the findings are pretty significant:

To date there have been no randomized trials examining the impact of microcredit. Using such a design, 52 of 104 slums in Hyderabad, India were randomly selected for opening of an MFI branch while the remainder were not. We show that the intervention increased total MFI borrowing, and study the effects on new business starts, investment, and consumption. Households with an existing business at the time of the program invest in durable goods, and their profi ts increase. Households with high propensity to become business owners see a decrease in nondurable consumption, consistent with the need to pay a fixed cost to enter entrepreneurship. Households with low propensity to become business owners see nondurable spending increase. We find no impact on measures of health, education, or women’s decision-making.

Ryan Hahn puts it this way: The verdict is in on microfinance. . . . And it’s not pretty.” He means that microfinance does appear to have a positive marginal effect on business formation and expansion, but the effect is modest and does not (at least within a 15-18-month timeframe) have any discernible effect on well-being.

More “New Economy” Hyperbole

| Peter Klein |

Wired’s Chris Anderson drinks the New Economy Kool-Aid. It’s the same old argument — information technology reduces transaction costs, leading to a radical disaggregation of industry and society — still supported by little more than a few colorful anecdotes, not any kind of systematic analysis. The new twist is the financial crisis, described by Anderson as “not just the trough of a cycle but the end of an era.”

What we have discovered over the past nine months are growing diseconomies of scale. Bigger firms are harder to run on cash flow alone, so they need more debt (oops!). Bigger companies have to place bigger bets but have less and less control over distribution and competition in an increasingly diverse marketplace. . . . The result is that the next new economy, the one rising from the ashes of this latest meltdown, will favor the small.

Nonsense. The major banks, the Chrysler corporation, and whoever is next to fail have not become nimbler and smaller, but larger; they have become part of the Federal government. Fannie and Freddie have swollen and taken on additional responsibilities. The financial crisis, as argued repeatedly on these pages, was spawned by a credit bubble brought about by loose monetary policy and massive government subsidization of the home mortgage market. It has nothing to do with firms being too large or somehow failing to take advantage of the Next Big Thing in social networking or cloud computing. I mean, seriously, is there anything here that couldn’t have been written ten years ago?

To all the usual reasons why small companies have an advantage, from nimbleness to risk-taking, add these new ones: The rise of cloud computing means that young firms no longer have to buy their own IT equipment, which helps them avoid having to raise money or take on debt. Likewise, the webification of the supply chain in many industries, from electronics to apparel, means that even the tiniest companies can now order globally, just like the giants. In the same way a musician with just a laptop and some gumption can accomplish most of what a record label does, an ambitious engineer can invent and produce a gadget with little more than that same laptop.

Bah. Humbug.

Deregulation and the Financial Crisis

| Peter Klein |

Niall Ferguson joins Charles Calomiris, Jerry O’Driscoll, Arnold Kling, and many others in questioning the supposed link between “deregulation” and the financial crisis. As Ferguson emphasizes, the timing is all wrong; there is no time-series correlation between specific patterns of regulation and deregulation and particular financial or economic outcomes. The relaxation of Glass-Steagall restrictions on universal banking is an oft-cited example, but, as these writers point out, no one has offered any specific mechanism by which universal banking contributed to the problem (indeed, the opposite is likely to be true). The “laissez-faire caused the crisis” meme may be pithy, but is there any systematic theoretical or empirical evidence for it?

Ferguson has the best line (suggested by Luke): “It is indeed impressive how rapidly the economists who failed to predict this crisis . . . have been able to produce such a satisfying story about its origins.”

Elfenbein and Zenger on Social Capital

| Peter Klein |

Congratulations to Dan Elfenbein and Todd Zenger for winning the ACAC Best Paper Award for “The Economics of Social Capital in De-Socialized Exchange.” Their paper addresses one of my pet peeves, the expansive use of “capital” to describe any ill-defined substance that accumulates and has value. Hence knowledge, experience, and skills become “human capital” or “knowledge capital”; relationships become “social capital”; brand names become “reputation capital”; and so on. I fear this terminology obfuscates more than it clarifies.

I don’t mind using these terms in a loose, colloquial sense: By going to school I’m investing in human capital or diversifying my stock of human capital; if this gets me a high-paying job I’m earning a good return on my human capital; as I get old I forget new things, so my human capital is depreciating rapidly; and so on.

But we shouldn’t take these metaphors too literally. In economic theory capital refers either to financial capital or to a stock of heterogeneous alienable assets, goods that can be exchanged in markets and analyzed using price theory. Their rental prices are determined by marginal revenue products and their purchase prices are given by the present discounted value of these future rents. Knowledge is not, strictly speaking, capital, because it is not traded in markets does not have a rental or purchase price. What markets trade and price is labor services, and it is impossible to decompose the payments to labor (wages) into separate “effort” and “rental return on human capital” components. Some labor services command a higher market price than others because they have a higher marginal revenue product. Some of this wage premium may be due to intelligence or experience, some due to complementarities with other human or nonhuman assets, some due to hard work, and so on. But these are all determinants of the MRP, and hence the wage, not different kinds of factor returns. (more…)

Bad to Awful?

| Peter Klein |

Via John Hagel, here’s a Business Week preview of Jim Collins’s new book, How the Mighty Fall, and How Some Companies Never Give In, a profile of once-successful firms that go under. Will the new book avoid the core methodological fallacy that doomed Collins’s earlier work? Unfortunately, it doesn’t appear so:

At our research lab [sic], we’d already been discussing the possibility of a project on corporate decline, in part because some of the great companies we’d profiled in the books Good to Great and Built to Last had subsequently lost their positions of prominence. On one level this fact didn’t cause much angst; just because a company falls doesn’t invalidate what we can learn by studying that company when it was at its historical best.

True, but without some mechanism for distinguishing treatment and control, such an investigation can never be anything more than a collection of interesting vignettes. Collins and his team seem unable to grasp the fundamental scientific principle of cause and effect. Just because a particular behavior corresponds to a particular outcome (be it success or failure), there is no way to know if that behavior contributed to the outcome, without studying individuals or organizations that exhibited the same behavior but experienced a different outcome.

I eagerly await Phil Rosenzweig’s next book: The Horns-and-Pitchfork Effect.

Confidence

| Peter Klein |

Craig Pirrong is concerned about the stress tests:

Craig Pirrong is concerned about the stress tests:

[Bernanke] emphasized that they were a “confidence-building exercise.” That seems like assuming the conclusion. I would like a fact-finding exercise, with a clear statement of the findings, good or bad. Stating that the objective is to build confidence suggests a pre-ordained result — Kabuki Theater. It’s like saying that something is needed to build “self-esteem.” Success builds self-esteem, not the other way around. Similarly, success builds confidence; confidence-building does not ensure success.

This reminds me of something I read the other day from Isabel Paterson, quoted by Stephen Cox:

[I am] tired of being told that “credit depends on confidence.” Fudge. Credit depends on real assets, sound money and a clean record. . . . When any one asks us to have confidence we are glad to inform him that the request of itself would shatter any remaining confidence in our mind.

Skepticism and Greed

| Dick Langlois |

One of my University colleagues, who works in instructional technology, sent a few of us a post from a mailing list-blog at Stanford called Tomorrow’s Professor. The site has a lot of interesting stuff on teaching and the academy, which O&M readers may find interesting. But this particular post, reprinted from a blog at the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching, prompted me to send in a response. Here is what I said. (Take a look at the original post, but I think you can get the idea from my comment.)

I certainly endorse what I take to be the central idea of post 944 — that students of business and economics would benefit from a liberal education.

Having said that, however, let me also note that I think the post gets things exactly — and perhaps dangerously — backwards in many ways. It is a constant trope in the popular press that the idea of “free markets” is some kind of dogma among economists (and perhaps society more broadly). In fact, economists believe that markets exist only within institutional structures, and economics — even so-called free-market economics — is actually about getting the institutions right, not about letting people do whatever they want.

In my view, moreover, economists are the real skeptics in the academy. Despite his (marketing) claim to being a “rogue” economist, Steve Levitt of Freakonomics fame is actually a better model of what most economists do than is Ben Bernanke or Alan Greenspan. Unlike most other academics, economists are rewarded for taking skeptical and iconoclastic positions, at least when they can back those positions up with hard data and clear analysis.

By contrast, few people outside of economics departments or business schools have any understanding whatever about how and when — or even whether — individual action can lead to beneficial unintended consequences. Economics is actually counter-intuitive in many ways. Humans evolved in small bands of hunter-gatherers, and as a result our intuitions about how a large open society operates are often wrong or backwards.

For all these reasons, it seems to me odd to suggest that economists (and students of economics) are dogmatic and would be made more skeptical and thoughtful about the economy by studying other liberal fields. In my experience, it’s rather the opposite. (Which is not to say, of course, that students won’t benefit in many ways from studying other fields.)

The post itself is a case in point. It starts out in the right direction with a marvelous story from Keynes about the nature of the money supply. But then it goes on to talk about “greed” as the central issue, ending with a quote from Roosevelt that “heedless self-interest” is bad economics. In fact, however, it is pointing to “greed” that is unexamined dogma. Why exactly has the level of greed changed over time? Is that really an explanation of anything? In stark contrast, many professional economists (including such serious scholars of the crisis as John Taylor and Karl Case) would point out that the most fundamental cause of the crisis was the expansive monetary policy of the Fed, which pumped money into the system and caused an asset bubble. Our hunter-gatherer ancestors endowed us with intuitions about greedy individuals; but they didn’t leave us intuitions about how a fiat money system works in a huge economy of non-face-to-face exchange. That we have to learn in an economics course.

My “No New Economy” Slides

| Peter Klein |

Here, for the curious, are my slides from this morning’s talk at the Law and Economics of Innovation conference, titled “Does the New Economy Need a New Economics?” (Short answer: no.) This will eventually morph into a paper so comments are most welcome (and thanks to those who have already helped). I’m looking forward to Susan Athey’s keynote later today.

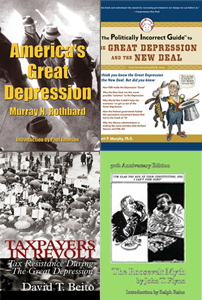

Cheer Up With the Depression Bundle

| Peter Klein |

Sorry, couldn’t resist the headline. But check it out: Murray Rothbard’s America’s Great Depression, Bob Murphy’s Politically Incorrect Guide to the Great Depression and the New Deal, Dave Beito’s Taxpayers in Revolt, and John T. Flynn’s Roosevelt Myth, all for $49! That’s quite an uplifting deal.

Sorry, couldn’t resist the headline. But check it out: Murray Rothbard’s America’s Great Depression, Bob Murphy’s Politically Incorrect Guide to the Great Depression and the New Deal, Dave Beito’s Taxpayers in Revolt, and John T. Flynn’s Roosevelt Myth, all for $49! That’s quite an uplifting deal.

More great news: Contra Keynes and Cambridge, vol. 9 of Hayek’s Collected Works, is now out in paperback from Liberty Fund, and just $14.50.

“New Economy” Bleg

| Peter Klein |

The heady dot-com days of the late 1990s brought breathy pronouncements from journalists and some academics that the “new economy” had changed all the old rules. Intellectual capital, not physical capital, is the source of value, so plant and equipment is irrelevant. Information goods are produced at zero marginal cost so firms should give away, rather than sell, their products. Profits don’t matter, only installed base counts. Managerial hierarchy is obsolete; cost curves are flat; supply-and-demand analysis is passé; even opportunity costs don’t matter anymore. The dot-com crash and subsequent shakeout brought many people back to their senses, but even today we continue to hear hyperbolic claims about the newness of the new economy.

I’d like to include some of these wildly exaggerated claims in my talk next week at the GMU/Microsoft forum. Can readers supply some quotes I can use (the more outrageous the better)? Like this:

[W]hen it comes to technology, even the most bearish analysts agree the microchip and Internet are changing almost everything in the economy.

— Greg Ip, WSJ, 18 January 2000

One curious aspect of the Network Economy would astound a citizen living in 1897: The very best gets cheaper each year. This rule of thumb is so ingrained in our contemporary lifestyle that we bank on it without marveling at it. But marvel we should, because this paradox is a major engine of the new economy. . . . Through most of the industrial age, consumers experienced slight improvements in quality for slight increases in price. But the arrival of the microprocessor flipped the price equation. In the information age, consumers quickly came to count on drastically superior quality for less price over time. The price and quality curves diverge so dramatically that it sometimes seems as if the better something is, the cheaper it will cost.

— Kevin Kelly, New Rules for the New Economy, 1998

Once a marketing gimmick, free has emerged as a full-fledged economy. . . . The rise of “freeconomics” is being driven by the underlying technologies that power the Web. Just as Moore’s law dictates that a unit of processing power halves in price every 18 months, the price of bandwidth and storage is dropping even faster. Which is to say, the trend lines that determine the cost of doing business online all point the same way: to zero.

— Chris Anderson, Wired, February 2008

Why have [stock] exchanges at all? Certainly not to help investors. Exchanges are at last being exposed as anachronisms, sustained by inertia and by the desire of incumbents, with help from regulators, to keep raking in monopoly rents. But the curtain is coming down.

— James Glassman, WSJ, 8 May 2000

I’m sure there are much more colorful statements (i.e., straw men for me to knock down) out there. Any suggestions?

Economists More Ethical; US Researchers Not

| Mike Sykuta |

Thanks to Josh Wright over at TOTM, I found Ben Edelman and Ian Larkin’s recent HBS Working Paper on “Demographics, Career Concerns or Social Comparison: Who Games SSRN Download Counts?” Their abstract reads:

We use a unique database of every SSRN paper download over the course of seven years, along with detailed resume data on a random sample of SSRN authors, to examine the role of demographic factors, career concerns, and social comparisons on the commission of a particular type of gaming: the selfdownloading of an author’s own SSRN working paper solely to inflate the paper’s reported download count. We find significant evidence that authors are more likely to inflate their papers’ download counts when a higher count greatly improves the visibility of a paper on the SSRN network. We also find limited evidence of gaming due to demographic factors and career concerns, and strong evidence of gaming driven by social comparisons with various peer groups. These results indicate the importance of including psychological factors in the study of deceptive behavior.

Their results suggest that papers published in the Economics Research Network of SSRN are significantly less likely to have “fraudulent” downloads (as measured in their paper) while papers in the Finance, Legal, and Accounting Networks are significantly more likely to have fraudulent downloads. Aren’t these the places in which ethics are being more broadly taught? Business and Law?

Among their other interesting results, papers by non-US authors are less likely to have fraudulent downloads. Perhaps surprisingly, one’s status on the tenure track seems not to be important, but one’s peer comparisons do. Sadly, there is no attempt to directly measure the O&M effect.

Down with Strunk and White

| Peter Klein |

Geoffrey Pullum does’t think much of the ubiquitous grammar guide, celebrating its 50th anniversary this week. The Elements of Style “does not deserve the enormous esteem in which it is held by American college graduates. Its advice ranges from limp platitudes to inconsistent nonsense. Its enormous influence has not improved American students’ grasp of English grammar; it has significantly degraded it.” (Thanks to Gary Peters for this link to a free version, available for just a few days.)

Keynesian Economics in a Nutshell

| Peter Klein |

An earlier post on Keynesian economics in four paragraphs has proven extremely popular. Here’s Keynesian economics in just one-and-a-half paragraphs, courtesy of Mario Rizzo:

Clearly, DeLong is a rigid aggregate demand theorist. He talks about output and employment as if it were some homogeneous thing. In his mind, macroeconomics is just about spending to increase the production of stuff. Yes, there is lip service to the idea that the stuff should have economic value. But that is easy when you assume that the only alternative is value-less idleness. . . .

The sectoral problems generated, not only by exogenous shocks but by the low interest rate policy of the Fed, are of critical importance. The aggregate demanders are blind to this.

Here at O&M we take the opposite perspective, namely that heterogeneity matters. Actually, as Mario has pointed out in a series of posts (1, 2, 3), Keynes himself was much better than his latter-day followers. Keynes may have been wrong — deeply, deeply wrong, in my view — but he was no fool. As for today’s Keynesians. . . .

Update (14 April): See also Mario’s fine essay in the April Freeman, “A Microeconomist’s Protest.”

Recent Comments