Posts filed under ‘Public Policy / Political Economy’

“Robert S. McNamara and the Evolution of Modern Management”

| Peter Klein |

That’s the title of a new HBR article by Phil Rosenzweig (author of the excellent Halo Effect). I’ve been interested in McNamara and his role in business history since grad school, when I was researching “management by the numbers” and similar techniques that flourished during the conglomerate boom in the 1960s. (See previous O&M posts on McNamara here and here.) Rosenzweig provides a nice summary of some of strengths and weaknesses of McNamara’s dispassionate, “rational,” quantitative approach (see especially the sidebar, “What the Whiz Kids Missed”). Lots of information and ideas related to decision theory, organizational design, multitasking, performance evaluation, innovation, etc. Excerpt:

Whether at Ford or in the military, in business or pursuing humanitarian objectives, McNamara’s guiding logic remained the same: What are the goals? What constraints do we face, whether in manpower or material resources? What’s the most efficient way to allocate resources to achieve our objectives? In filmmaker Errol Morris’s Academy Award–winning documentary The Fog of War, McNamara summarized his approach with two principles: “Maximize efficiency” and “Get the data.”

Yet McNamara’s great strength had a dark side, which was exposed when the American involvement in Vietnam escalated. The single-minded emphasis on rational analysis based on quantifiable data led to grave errors. The problem was, data that were hard to quantify tended to be overlooked, and there was no way to measure intangibles like motivation, hope, resentment, or courage. . . .

Equally serious was a failure to insist that data be impartial. Much of the data about Vietnam were flawed from the start. This was no factory floor of an automobile plant, where inventory was housed under a single roof and could be counted with precision. The Pentagon depended on sources whose information could not be verified and was in fact biased. Many officers in the South Vietnamese army reported what they thought the Americans wanted to hear, and the Americans in turn engaged in wishful thinking, providing analyses that were overly optimistic.

Ronald Coase’s New Book

| Peter Klein |

Yes, you read that correctly. Ronald Coase, who turns 100 later this month, has a new book coming out from Palgrave Macmillan and the Institute of Economic Affairs, How China Became Capitalist. It’s coauthored with Ning Wang, Coase’s former research assistant at Chicago and now an assistant professor at Arizona State, and scheduled for publication in June 2011.

Yes, you read that correctly. Ronald Coase, who turns 100 later this month, has a new book coming out from Palgrave Macmillan and the Institute of Economic Affairs, How China Became Capitalist. It’s coauthored with Ning Wang, Coase’s former research assistant at Chicago and now an assistant professor at Arizona State, and scheduled for publication in June 2011.

Examining the astonishing events that led to China’s transformation from a close socialist economy to an invincible manufacturing powerhouse of the global economy, How China Became Capitalist argues that the impact of events that led China to become capitalist could not have been predicted. From the death of Mao to China’s market reform and move to capitalism under the auspices of the Chinese Communist Party, How China Became Capitalist controversially argues that China’s growth potential will be inhibited in future without a vibrant market in ideas.

My Brush with Obamacare

| Scott Masten |

I had my first personal encounter with America’s new health care legislation last week. The University of Michigan’s current (i.e, pre-Obamacare) faculty-and-staff health care benefits provide health care coverage for faculty children up to age 25. As a result, my daughter, who turns 24 this next month, was eligible for an additional year of coverage under my benefits. Last week, the UM Benefits Office sent employees an email announcing the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act’s much-touted requirement that health care policies hereafter provide coverage of dependents up to age 26. The announcement added, “The health care reform law removes all previous and current eligibility requirements for coverage.” But then a little further down was the following: “In order to be eligible for coverage under your benefits, a dependent child must … not [be] eligible for health benefits through his or her own employer.” So my daughter, who was eligible to remain on my UM plan for another year before Obamacare, becomes ineligible January 1 because she works for a small company that offers a health plan. It’s not the end of the world, of course. My daughter (who lives at home) will be a bit poorer because she will have to pay for her own health care a year sooner than expected, and the coverage probably won’t be as comprehensive as the UM plan is. If that were the only issue, I wouldn’t have bothered with this post. (more…)

Report on the North Conference

| Peter Klein |

Responsibilities abroad kept me from attending the recent Douglass North celebration, but the University of Missouri was well represented by a group of energetic and enthusiastic PhD students, who sent me the following report:

Responsibilities abroad kept me from attending the recent Douglass North celebration, but the University of Missouri was well represented by a group of energetic and enthusiastic PhD students, who sent me the following report:

The conference on Legacy and Work of Douglass North was an outstanding meeting with discussions on the past, present, and future of the New Institutional Economics. Top scholars discussed the contribution and influence of North (and the New Institutional Economics) in a diverse range of fields, covering everything from the impact of the initial contributions to the outlook for continued research.

It’s hard to summarize the insights and contributions from six paper sessions, Elinor Ostrom’s keynote, and the roundtable on North and the Rise of the New Institutional Economics. One takeaway was the depth and breadth of North’s contributions – many speakers were North coauthors working on a wide variety of topics, from many different perspectives (economics, political science, history, cognition, etc.). North’s influence is huge across the social sciences.

One burning issue: what’s the next step for New Institutional Economics? Besides bridging or integrating Northean institutional analysis with Williamsonian organizational economics, many speakers emphasized the need to be more rigorous, to examine more details, to go farther than the “big picture” studies that are so prominent in the field. There are too many grand, sweeping claims, and not enough mundane, middle-of-the-road analysis. (John Nye, for example, expressed concern that some Northean ideas are very difficult to operationalize, a particular problem since younger scholars are confronted with very high standards for formalization, empirical technique, etc.) (more…)

Blinder: Keynesianism is Right, Because Keynesians Are Really Smart

| Peter Klein |

Alan Blinder’s defense of QE2 is as feeble as Mankiw’s defense of “emergency measures” more generally. Blinder’s argument is simply that QE2 isn’t all that different from standard Keynesian fine-tuning (true) and that Ben Bernanke is smarter than critics like Sarah Palin (duh).”To create the fearsome inflation rates envisioned by the more extreme critics, the Fed would have to be incredibly incompetent, which it is not.” This reminds me of Janet Yellen’s unfortunate 2009 statement that “the Fed’s analytical prowess is top-notch and our forecasting record is second to none. . . . With respect to our tool kit, we certainly have the means to unwind the stimulus when the time is right.”

Blinder apparently thinks that the anti-Keynesian backlash is just some quibbles about this little jot or tittle. He cannot grasp that the growing sentiment against monetary central planning, against fine-tuning, against the whole statist monetary establishment, is a rejection of Keynesianism at the most fundamental level. People are tired of the philosopher kings and their pretense of knowledge.

But this is folly to kings. Consider Blinder’s criticism of Bernanke:

What the Fed proposes to do is neither foolproof nor perfect. Frankly, it’s not the policy I would choose. As I’ve written on this page, I’d like the Fed to purchase private securities and to reduce the interest rate it pays on reserves, even turning it negative. The latter would blast reserves out of banks into some productive uses.

Ah, to think like a king! But the days of the monetary monarchy may be numbered.

The Thin Mint Effect

| Peter Klein |

A new study finds that as nonprofit organizations increase their for-profit activities, the share of resources going to the core mission decreases. (Thanks to Fast Company for the link and the Thin Mint reference.)

A new study finds that as nonprofit organizations increase their for-profit activities, the share of resources going to the core mission decreases. (Thanks to Fast Company for the link and the Thin Mint reference.)

This strikes me as a good illustration of multitask principal-agent problems. The output of for-profit activities is more easily measured than the output of nonprofit activities, giving agents (under performance-based pay) the incentive to increase effort toward those for-profit activities. Mises’s discussion of performance measurement and delegation in Bureaucracy comes to mind as well.

Man Bites Dog …

| Scott Masten |

. . . and government swears it acts politically and is incompetent.

This might just be worth the cost to the U.S. taxpayer of bailing out GM. From GM’s prospectus for its upcoming IPO (via NPR):

…to the extent the UST [United States Treasury] elects to exert such control in the future, its interests (as a government entity) may differ from those of our other stockholders. In particular, the UST may have a greater interest in promoting U.S. economic growth and jobs than our other stockholders. For example, while we have repaid in full our indebtedness under our credit agreement with the UST that we entered into on the closing of the 363 Sale, a continuing covenant requires that we use our commercially reasonable best efforts to ensure, subject to exceptions, that our manufacturing volume in the United States is consistent with specified benchmarks. (p. 6)

We have determined that our disclosure controls and procedures and our internal control over financial reporting are currently not effective. The lack of effective internal controls could materially adversely affect our financial condition and ability to carry out our business plan. (p.29)

Now, the next time anyone says otherwise, you have can point to this.

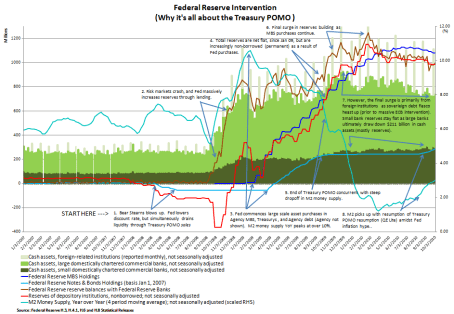

A POMO Picture is Worth a Thousand Words

| Peter Klein |

Not “pomo” as in Pomo Periscope, but “POMO” as in Permanent Open Market Operations. A fascinating graphic from Bob English (via EB) showing how the Fed is using its new tool (click to enlarge). In case you were worrying about the Fed “standing idly by” . . . .

The Legacy and Work of Douglass North

| Peter Klein |

Washington University, St. Louis is hosting a major international conference, 4-6 November, on the Legacy and Work of Douglass North. The all-star panel includes Lee Alston, Robert Bates, Joel Mokyr, Elinor Ostrom, Ken Shepsle, Barry Weingast, and many others. The conference is organized by Wash U’s Center for New Institutional Social Science.

In other conference news, the CFP for next year’s Atlanta Competitive Advantage Conference, 17-19 May 2011, has been posted. Featured presenters include Jay Barney, Joel Baum, and Rebecca Henderson.

Assorted Links

| Peter Klein |

- A new paper by Randall Morck and Bernard Yeung, “Agency Problems and the Fate of Capitalism.” A very good comparative-institutional analysis of shareholder democracy and its benefits and costs relative to “stakeholder” models.

- A Washington Post story on “moral licensing” (via Sheen Levine) — suggesting that some people view ethical behavior, like goods and services, in terms of trade-offs at the margin!

- A call for contributions to The Ethics and Economics of Agrifood Competition, a Springer volume in preparation by my colleague Harvey James.

- Videos and papers from the Coase centenary conference held last year at the University of Chicago Law School.

Cui Bono Blues

| Scott Masten |

No, not some long lost Robert Johnson classic. I’m referring to the Justice Department’s suit filed earlier this week against Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan, with “hints” from the Justice Department that more health industry suits are in the pipeline. The allegation is that BCBCM used most-favored nation agreements with hospitals to reduce “competition in the sale of health insurance in markets throughout Michigan by inhibiting hospitals from negotiating competitive contracts with Blue Cross’ competitors.”

I don’t know enough about the case to say anything about its merits at this point. But I do find curious the DOJ’s choice of a nonprofit for its demonstration project on controlling healthcare costs through the antitrust laws. It reminds me of [uh-oh, here it comes — Ed.] (more…)

American Exceptionalism

| Dick Langlois |

From a review by Andrei S. Markovits of Peter Baldwin, The Narcissism of Minor Differences: How America and Europe Are Alike — An Essay in Numbers:

Baldwin commences his data-rich book with the economy, where he demonstrates convincingly that the stereotype of America’s being ruled by an unfettered free market with minimal state intervention and low taxes, while Europe is controlled by the dirigiste étatism of faceless bureaucrats who stifle all market initiatives with high taxes and cumbersome regulations, is totally erroneous. Indeed, Baldwin musters impressive data that a) taxes on income and profits are lower in ten European countries than they are in the United States, b) America’s income tax progressivity hovers in the middle among European states, c) its taxation of the wealthy far exceeds those in any European country, and d) its property taxes are only surpassed by those of Luxembourg, France, and the United Kingdom.

The U.S. is in the middle of the pack in almost all other statistical categories as well. The book is a tour de force, says the reviewer, but it will have no impact, since the idea — or, rather, multiple formulations of the idea — that the U.S. and Europe are fundamentally different is so strongly entrenched on both sides of the political spectrum on both sides of the Atlantic.

The (Very) Early Adoption of Modern HRM Practices

| Peter Klein |

Bruce Kaufman’s book Hired Hands or Human Resources? Case Studies of HRM Programs and Practices in Early American Industry (Cornell U. P., 2010) shows that US firms started adopting “modern” HRM practices around World War I, not during the New Deal, and they did so primarily to increase productivity, not in response to union or government pressure. Writes reviewer Chad Pearson:

Kaufman illustrates the ways in which several companies created professional human resource management (HRM) models after World War I. This is the most valuable part of the book principally because he used the records of the Industrial Relations Councilors (IRC), a consulting firm that began assisting employers in the 1910s. The IRC offered consulting services, provided research, and ran courses on industrial relations topics throughout the nation. Kaufman, the first scholar to examine these records, believes that “no other [industrial relations consulting firm] before World War II had IRC’s reach and influence” (p. 108). . . .

In most cases, these firms, in consultation with the IRC, began to, in Kaufman’s words, treat labor not as “a short-term commodity,” as was common in previous decades, but rather as “a longer-term human capital asset (the ‘human resource’ approach)” (p. 219). Why? Pressure from unions and the law were factors, but “they were less than half the story in the time period we are examining” (p. 228). In his view, employers’ desires to improve “management and productivity” better explain why companies improved workplace conditions (p. 227).

Labor historians and specialists in business regulation used to focus on the Progressive Era as a watershed period — e.g., Wiebe (1962), Weinstein (1981), and of course Kolko (1977) — but interest seems to have waned.

Burning Down the House

| Scott Masten |

Peter posted a Facebook link to a Jeff Tucker post on the Mises Economics Blog commenting on the news report about the Tennessee man who didn’t pay his annual $75 fire protection services fee, and the fire department from the neighboring town let his house burn down. Peter, Jeff, and Clifford Grammich (who commented on Peter’s post) cover the issues pretty well. My guess is that the reason governments rather than private companies generally provide fire services has a lot to do with the difficulty of pricing fire services. (The Tennessee case involved a quasi-market transaction in that residents outside of South Fulton paid the city of South Fulton for fire protection.) It is certainly conceivable that private fire companies could offer homeowners and businesses a choice between (i) prepaid fire service for an annual fee and (ii) on-demand fire service. But how would you determine the price of the latter? I’m pretty sure you wouldn’t want to negotiate the price while your house is burning down. (Talk about temporal specificity!) And you wouldn’t want to negotiate the price after the fact either: Gee, guys, thanks for saving my house; can I buy you all a beer? (more…)

Cities and the Fetters of Nations

| Dick Langlois |

In Cities and the Wealth of Nations, Jane Jacobs argued that currencies should be promulgated by cities not nation states. If, for example, the currency of Detroit (the cadillac, let us say) could have floated against the currency of San Francisco (the silicon) during the late 20th century, there would have been another margin (other than the movement of capital and people) on which adjustments to technological change and shifting relative prices could have taken place, perhaps making Detroit less of a disaster area. I always found this idea appealing; but, not being a monetary economist and not having heard the idea discussed within professional economics, I wondered whether I might be missing some obvious counter-argument. Recently, however, I saw an NBER Working paper by Barry Eichengreen and Peter Temin that seems to make a similar point. Called “Fetters of Gold and Paper,” it argues that the euro and the dollar-renminbi peg are fixed-exchange-rate regimes like the gold standard. Such fixed-rate regimes may lower transaction costs in good times, but they prevent necessary adjustments in bad times, potentially leading to crises. Adjustment takes place via deflation that would otherwise have taken place through exchange-rate movement.

This is essentially the Eichengreen-Temin story about the Great Depression, which (to oversimplify) isn’t really very different from the Monetarist version. The Monetarists essentially say that gold wasn’t a fetter because there was never a real gold standard; it was a badly manipulated facsimile, which the Fed mismanaged. Eichengreen and Temin acknowledge this, but apply spin so that it was the mentalité of the gold standard that caused monetary authorities to behave as they did. In any case, as Eichengreen and Temin point out, the euro is actually a much stronger version of the fetters problem, since there is no adjustment mechanism akin to gold flows, however imperfect that mechanism might have been. Moreover, countries could (and eventually did) go off the gold standard; but there is no mechanism for countries to pull out of the euro without causing a major crisis. Interestingly, they see Bretton Woods as less of a problem, since there were international adjustment mechanisms in place. Also interestingly (for two economists of a Keynesian bent), they worry at length about the federal budget deficit and the level of government spending in the face of the renminbi peg and the current-account deficit. Usually, free-market economists worry about the budget deficit but not the current-account deficit, whereas left-of-center economists worry about the current account but not the budget. The renminbi peg makes them linked problems.

Which brings us back to Jacobs. The American dollar — one currency for all 50 states — was a prime model for the euro. And a Google search brings up dozens of comparisons between California and Greece. Why should the nation-state — whether the US or Europe — be the appropriate geographical domain of a currency?

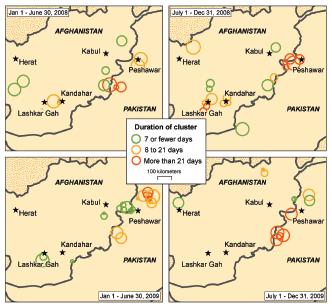

Analyzing the WikiLeaks Data

| Peter Klein |

Once more on WikiLeaks: A team of University of Colorado researchers has already produced a geospatial analysis of the incident reports contained in the dataset. “By mapping the violence and examining its temporal dimensions, the authors explain its diffusion from traditional foci along the border between the two countries. While violence is still overwhelmingly concentrated in the Pashtun regions in both countries, recent policy shifts by the American and Pakistani governments in the conduct of the war are reflected in a sizeable increase in overall violence and its geographic spread to key cities. . . .” This is exactly the kind of analysis the military intelligence agencies are not doing, or at least not sharing.

Economists, geographers, entrepreneurship and innovation researchers, and other social scientists have a lot of expertise in network and cluster analysis. Why not turn them loose on these kinds of raw data? It’s also cheap: as Karen Kwiatkowski notes, “[t]he study was honestly, scientifically, and nimbly completed and published at no direct cost to the intelligence community. It was made possible by the decentralization, fluidity, and constant sharing and shifting of roles and responsibilities that comprise the Internet.”

Bruce Caldwell on The Road from Mont Pèlerin

| Peter Klein |

Don’t miss Bruce Caldwell’s review of Philip Mirowski and Dieter Plehwe, eds., The Road from Mont Pèlerin: The Making of the Neoliberal Thought Collective (Harvard, 2009). “Mont Pèlerin” refers, of course, to the Mont Pèlerin Society, the association of classical liberal academics and journalists founded by Hayek in 1947. Bruce finds the volume informative, despite its frequently disdainful tone toward its subjects. He also raises an important general point, one that I’ve wrestled with a lot since the financial crisis: does anybody listen to us?

Don’t miss Bruce Caldwell’s review of Philip Mirowski and Dieter Plehwe, eds., The Road from Mont Pèlerin: The Making of the Neoliberal Thought Collective (Harvard, 2009). “Mont Pèlerin” refers, of course, to the Mont Pèlerin Society, the association of classical liberal academics and journalists founded by Hayek in 1947. Bruce finds the volume informative, despite its frequently disdainful tone toward its subjects. He also raises an important general point, one that I’ve wrestled with a lot since the financial crisis: does anybody listen to us?

The second question [raised by the book] has to do with the potency of intellectuals to shape world events or, more narrowly, even economic and social policy. It is evident that members of the Mont Pèlerin Society, for all of their diversity, still preferred some form of liberalism . . . to other ways of organizing economic and political affairs. But how important were they in the emerging global consensus that began in the 1980s in favor of trade liberalization and privatization? Were not, for example, the dismal performance of Keynesian demand management policies in the United States, Britain, and elsewhere in the 1970s; the heavy-handed actions of the trade unions in Britain during the “Winter of Discontent”; the sclerotic performance of countries like India who had embraced a modified version of the planning model for their own; and, of course, the patent economic and political failures of the East Bloc, far more important in turning the tide, however briefly, towards globalization? Was not George Stigler (himself a founding member of the Society) right in his comment about economists that “our influence appears to be powerful only when we support policies ripe for adoption” (Stigler 1987, p. 11)?

Department of “Duh”

| Peter Klein |

It must be acknowledged, however, that a researcher’s political ideology or vested interest in a particular theory can still enter even ostensibly descriptive analysis by the data set chosen for the research; the mathematical transformations of raw data and the exclusion of so-called outlier data; the specific form of the mathematical equations posited for estimation; the estimation method used; the number of retrials in estimation to get what strikes the researcher as “plausible” results, and the manner in which final research findings are presented.

That’s Uwe Reinhardt, writing a NY Times op-ed that could have been titled “A Mainstream Economist Tries to Come to Grips with Kaldor-Hicks Efficiency.” It’s actually a pretty thoughtful and informative discussion that exposes some of the fatal — to my mind, anyway — flaws of the Kaldor-Hicks concept. But Reinhardt implies, unfortunately, that virtually every economist accepts the Kaldor-Hicks principle as a normative standard. There is actually a fair amount of dissent, not only from Austrians but also from people like Jon Elster and John Roemer. As Gary Lawson notes in an excellent survey of welfare economics concepts, the Kaldor-Hicks criterion, in practice, is

as useless as Pareto superiority. Kaldor-Hicks efficiency purchases its coherence by requiring that compensation be hypothetically possible in such a way as to guarantee that each person, by her own standards, does not come away a loser, just as strict Paretianism requires that each person judge herself to be as well off or better off than before. All it takes to make the universe of Kaldor-Hicks-efficient transactions an empty set is one person who sincerely cannot be bought-that is, a person who values autonomy, either his own or that of others, so highly that no amount of after-the-fact compensation could possibly leave him as well off as he would have been had the loss never been inflicted. (without consent) in the first place. In a large population, no legal rule [or other reallocation of resources] will ever satisfy the Kaldor-Hicks efficiency criterion.

WikiLeaks and Napster

| Peter Klein |

Apropos my WikiLeaks post, comparing the recent data dump to the data-sharing and data-mining practices increasingly common in academia, a Thursday New Yorker post by Raffi Khatchadourian takes the New Economy framing even further, comparing Wikileaks to Napster. “Shutting WikiLeaks down — assuming that this is even possible — would only lead to copycat sites devised by innovators who would make their services even more difficult to curtail.” The recording industry shut down Napster, spawning Bittorrent — a far more dangerous competitor. Khatchadourian says the Defense Department should “consider WikiLeaks a competitor rather than a threat, and to recognize that the spirit of transparency that motivates [Wikileaks founder Julian] Assange and his volunteers is shared by a far wider community of people who use the Internet.” Had the DoD had released the footage of the 2007 Apache helicopter attack itself, rather than waiting for WikiLeaks to publish it on YouTube, it could probably have contained the damage much more effectively. Naturally, I wouldn’t expect the DoD — or the RIAA — to be that smart. (HT to TechDirt via David Veksler.)

Apropos my WikiLeaks post, comparing the recent data dump to the data-sharing and data-mining practices increasingly common in academia, a Thursday New Yorker post by Raffi Khatchadourian takes the New Economy framing even further, comparing Wikileaks to Napster. “Shutting WikiLeaks down — assuming that this is even possible — would only lead to copycat sites devised by innovators who would make their services even more difficult to curtail.” The recording industry shut down Napster, spawning Bittorrent — a far more dangerous competitor. Khatchadourian says the Defense Department should “consider WikiLeaks a competitor rather than a threat, and to recognize that the spirit of transparency that motivates [Wikileaks founder Julian] Assange and his volunteers is shared by a far wider community of people who use the Internet.” Had the DoD had released the footage of the 2007 Apache helicopter attack itself, rather than waiting for WikiLeaks to publish it on YouTube, it could probably have contained the damage much more effectively. Naturally, I wouldn’t expect the DoD — or the RIAA — to be that smart. (HT to TechDirt via David Veksler.)

Add to: Facebook | Digg | Del.icio.us | Stumbleupon | Reddit | Blinklist | Twitter | Technorati

Regulatory Capture

| Dick Langlois |

I seem to be on the “communitarianism” mailing list of Amitai Etzioni, missives from which are usually good for a cold frisson of annoyance. The most recent one seemed promising, however, as it touted a paper revisiting the capture theory of regulation. Many people have rightly criticized the Dodd-Frank Act for piling on unnecessary administrative regulation despite the fact that (A) regulation was already extensive and provided all the powers that would have been needed to avert the crisis and (B) much of the new regulation is aimed at activities that have nothing to do with the financial crisis. Etzioni points out that the potential for regulatory capture is an additional reason for concern. Quite so. Dependably, however, Etzioni comes to the wrong conclusion about the nature of the problem and how to fix it. To Etzioni, the problem is not the inherent liabilities of administrative regulation but the specter of private money corrupting the system. (Notably, his examples do not include the money of labor unions, which have captured, at the very least, vast swaths of the Labor and Education Departments.) As political speech is a topic on which I have already fulminated at some length, I will just add that, even in a world in which regulators were somehow insulated from financial temptation, there would still be capture: the operation of regulatory agencies depends on the possession of large amounts of specialized knowledge in whose generation the subjects of regulation have considerable, and oftentimes overwhelming, advantage.

Add to: Facebook | Digg | Del.icio.us | Stumbleupon | Reddit | Blinklist | Twitter | Technorati

Recent Comments