Posts filed under ‘Theory of the Firm’

Jackson Nickerson at SMG

| Nicolai Foss |

When I was a graduate student 20-25 years ago I remember transaction cost economics being routinely mocked by all and sundry for “being static,” “neglecting learning,” and “not saying anything about innovation and entrepreneurs,” in addition, of course, to the usual charges of working with an impoverished and overly cynical view of human nature.

While TCE still highlights opportunism as a key assumption, it is fair to say that over the last decade important work has brought dynamics, learning and innovation within the orbit of TCE. This has mainly been brought about by a coterie — some of which are former students of Oliver Williamson — such as Nicholas Argyres, Kyle Mayer, Todd Zenger, Steve Michael, O&M’s Peter Klein, and last, but certainly not least, Jackson Nickerson.

Jackson is the author of a large number of truly innovative papers in management research and economics, many of which have a TCE bent. Thus, with Todd Zenger he has done important work on envy (and other aspects of social comparison processes) as an antecedent of internal transaction costs, on why firms seem to switch between extremes in their organizational forms, and, again with Zenger, he has pioneered a “problem-solving approach” to economic organization.

My department will feature this extremely original thinker as a speaker in our seminar series on Friday (here). Jackson will present a novel take on the dominant design stream of thinking about industry evolution, building on the US auto industry data base that (his co-authors) Lyda Bigelow and Nick Argyres have successfully exploited in earlier publications. Will be exciting!!

Cognition and Capabilities

| Dick Langlois |

The title of this paper caught my attention.

“Cognition & Capabilities: A Multi-Level Perspective”

J. P. Eggers and Sarah Kaplan

Academy of Management Annals 7(1): 293-338Research on managerial cognition and on organizational capabilities has essentially developed in two parallel tracks. We know much from the resource-based view about the relationship between capabilities and organizational performance. Separately, managerial cognition scholars have shown how interpretations of the environment shape organizational responses. Only recently have scholars begun to link the two sets of insights. These new links suggest that routines and capabilities are based in particular understandings about how things should be done, that the value of these capabilities is subject to interpretation, and that even the presence of capabilities may be useless without managerial interpretations of their match to the environment. This review organizes these emerging insights in a multi-level cognitive model of capability development and deployment. The model focuses on the recursive processes of constructing routines (capability building blocks), assembling routines into capabilities, and matching capabilities to perceived opportunities. To date, scholars have focused most attention on the organizational-level process of matching. Emerging research on the microfoundations of routines contributes to the micro-level of analysis. The lack of research on capability assembly leaves the field without a bridge connecting the macro and micro levels. The model offers suggestions for research directions to address these challenges.

The reason it caught my eye is that some 16 years ago I published a paper with exactly the same title (albeit with a different subtitle). Of course, I didn’t approach the issue in exactly the way these authors do, which is obviously close to Nicolai’s work on microfoundations. But I did arguably try to “link the two sets of insights,” and I did not do so “only recently.”

Hart on Incomplete Contracts

| Peter Klein |

Transaction cost economics, the property-rights approach to the firm, and the judgment-based view all assume that contracting parties cannot sign complete, contingent contracts, in which case firm boundaries would be arbitrary and unimportant. TCE tends to attribute incompleteness to bounded rationality, while the judgment-based view appeals to Knightian uncertainty and subjectivism to describe markets for judgment are incomplete. The property-rights approach of Grossman, Hart, and Moore did not have an explicit theory of incompleteness, which critics such as Maskin and Tirole saw as a major weakness.

Oliver Hart has written a series of recent papers on “reference points” as a new explanation for incompleteness. The newest, released today as an NBER working paper (with Maija Halonen-Akatwijuka), is the most explicit. It argues that parties deliberately leave gaps in contracts because explicit clauses can make it more difficult for parties to parties to renegotiate after the fact. Check it out and see what you think.

More is Less: Why Parties May Deliberately Write Incomplete Contracts

Maija Halonen-Akatwijuka, Oliver D. Hart

NBER Working Paper No. 19001, April 2013Why are contracts incomplete? Transaction costs and bounded rationality cannot be a total explanation since states of the world are often describable, foreseeable, and yet are not mentioned in a contract. Asymmetric information theories also have limitations. We offer an explanation based on “contracts as reference points”. Including a contingency of the form, “The buyer will require a good in event E”, has a benefit and a cost. The benefit is that if E occurs there is less to argue about; the cost is that the additional reference point provided by the outcome in E can hinder (re)negotiation in states outside E. We show that if parties agree about a reasonable division of surplus, an incomplete contract can be strictly superior to a contingent contract.

Shelanski Tapped for Top Regulatory Post

| Peter Klein |

My old classmate, fellow Oliver Williamson student, and coauthor Howard Shelanski has been nominated to head the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs (the post typically described as Regulation Czar). Howard was in the joint PhD-JD program at Berkeley, went on to clerk for Antonin Scalia, joined the faculty at Berkeley’s School of Law, and served in a number of regulatory posts before moving to Georgetown. He currently heads the FTC’s Bureau of Economics.

My old classmate, fellow Oliver Williamson student, and coauthor Howard Shelanski has been nominated to head the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs (the post typically described as Regulation Czar). Howard was in the joint PhD-JD program at Berkeley, went on to clerk for Antonin Scalia, joined the faculty at Berkeley’s School of Law, and served in a number of regulatory posts before moving to Georgetown. He currently heads the FTC’s Bureau of Economics.

Howard’s a super-smart guy, whom I’d describe as an antitrust moderate (unlike me, an anti-antitrust extremist). He’s sympathetic to “post Chicago” antitrust theory and policy, but more of a nuts-and-bolts, case-by-case guy. I’m not a fan Cass Sunstein, current head of the OIRA, and I expect to like Howard’s performance much better. Howard doesn’t share Sunstein’s enthusiasm for behavioral analysis, for example, as seen in an interview last December, where he said this about the role of behavioral economics in antitrust:

I think there is a role, but one needs to be very modest and cautious. There has been a lot written and a lot said about how behavioral economics fundamentally undermines the models on which we do antitrust analysis. And I think most people involved with antitrust enforcement, most people who think about competition issues, would disagree that there is some fundamental new paradigm shift in the works. But behavioral economics does supply insights into how consumers might respond to certain kinds of information, contracting practices, or pricing schemes. This can be very useful to understanding certain kinds of market performance and has led to greater modesty about imputing perfect foresight or rationality to consumers.

But one needs to understand that that is not the sign of a broader behavioral economics revolution in antitrust.

My general feelings about regulatory czars are well summarized by this passage from Fiddler on the Roof, quoted today by Danny Sokol in the same context:

Young Jewish Man: Rabbi, may I ask you a question?

Rabbi: Certainly, my son.

Young Jewish Man: Is there a proper blessing for the Tsar?

Rabbi: A blessing for the Tsar? Of course! May God bless and keep the Tsar . . . far away from us!

AMP Symposium on Private Equity

| Peter Klein |

The new issue of the Academy of Management Perspectives features a symposium, edited by Mike Wright, on “Private Equity: Managerial and Policy Implications.” The symposium includes “Private Equity, HRM, and Employment” by Mike with Nick Bacon, Rod Ball, and Miguel Meuleman; “The Evolution and Strategic Positioning of Private Equity Firms” by Robert E. Hoskisson, Wei Shi, Xiwei Yi, and Jing Jin; and “Private Equity and Entrepreneurial Governance: Time for a Balanced View” by John L. Chapman, Mario P. Mondelli, and me. The symposium came out very nicely, if I may say so, covering a variety of strategic, entrepreneurial, and organizational issues related to private equity firms and companies receiving private equity finance.

In his introduction Mike highlights five main contributions:

First, the papers address the need to consider the systematic evidence on the managerial and strategic aspects of PE, in relation to both portfolio firms and PE firms, which has been largely fragmented if not nonexistent. Second, the papers analyze the impact of PE during economic downturns and demonstrate the underlying resilience of PE-backed portfolio firms. Third, the symposium provides an opportunity to develop insights that compare the managerial impact of PE with different forms of ownership and governance. Fourth, the articles in this symposium highlight the heterogeneity of the private equity phenomenon. Finally, in the context of continuing public attention to PE, which has been heightened by the U.S. presidential race and the global recession, the evidence presented in this symposium paints a rather more positive view than the hyperbole of some of the industry’s critics would suggest. Taken together, these contributions indicate a need for caution in attempts to tighten the regulation of PE lest the economic, financial, and social benefits be lost.

New Frontiers in Marketing

| Peter Klein |

“Not only do we manufacture here at home, we also economize on bounded rationality while simultaneously safeguarding transactions against the hazards of opportunism!”

Rational Inattention

| Dick Langlois |

The idea of attention as a scarce resource goes back at least to Herbert Simon and Nelson and Winter. I hadn’t seen much application of this idea in a while until I ran across this interesting paper called “Rational Inattention and Organizational Focus” by Wouter Dessein, Andrea Galeotti, and Tano Santos. Here’s the abstract:

We examine the allocation of scarce attention in team production. Each team member is in charge of a specialized task, which must be adapted to a privately observed shock and coordinated with other tasks. Coordination requires that agents pay attention to each other, but attention is in limited supply. We show how organizational focus and leadership naturally arise as the result of a fundamental complementarity between the attention devoted to an agent and the amount of initiative taken by that agent. At the optimum, all attention is evenly allocated to a select number of “leaders”. The organization then excels in a small number of focal tasks at the expense of all others. Our results shed light on the importance of leadership, strategy and “core competences” in team production, as well as new trends in organization design. We also derive implications for the optimal size or “scope” of organizations: a more variable environment results in smaller organizations with more leaders. Surprisingly, improvements in communication technology may also result in smaller but more balanced and adaptive organizations.

Apparently, Dessein has been working on attention models for some time, though I hadn’t noticed. (But, of course, Peter had.) I should also note that this model is similar in spirit to the work of Sharon Gifford, now 20 years old, which Dessein et al. do not cite.

Incomplete Contracts and the Internal Organization of Firms

| Peter Klein |

That’s the title of a new NBER paper by Philippe Aghion, Nicholas Bloom, and John Van Reenen, indicating that organization design, from the perspective of incomplete-contracting theory, continues to be a hot topic among the top economists. Like all NBER papers this one is gated, but intrepid readers may be able to locate a freebie.

Incomplete Contracts and the Internal Organization of Firms

Philippe Aghion, Nicholas Bloom, John Van ReenenNBER Working Paper No. 18842, February 2013

We survey the theoretical and empirical literature on decentralization within firms. We first discuss how the concept of incomplete contracts shapes our views about the organization of decision-making within firms. We then overview the empirical evidence on the determinants of decentralization and on the effects of decentralization on firm performance. A number of factors highlighted in the theory are shown to be important in accounting for delegation, such as heterogeneity and congruence of preferences as proxied by trust. Empirically, competition, human capital and IT also appear to foster decentralization. There are substantial gaps between theoretical and empirical work and we suggest avenues for future research in bridging this gap.

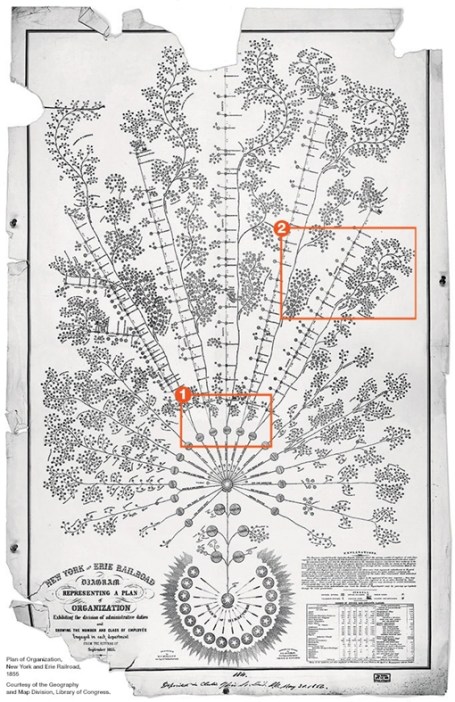

The First Modern Organizational Chart

| Peter Klein |

It was designed in 1854 for the New York and Erie Railroad and reflects a highly decentralized structure, with operational decisions concentrated at the local level. McKinsey’s Caitlin Rosenthal describes it as an early attempt to grapple with “big data,” one of today’s favored buzzwords. See her article, “Big Data in the Age of the Telegraph,” for a fascinating discussion. And remember, there’s little new under the sun (1, 2, 3).

Armen Alchian (1914-2013)

| Peter Klein |

Armen Alchian passed away this morning at 98. We’ll have more to write soon, but note for now that Alchian is one of the most-often discussed scholars here at O&M. A father of the “UCLA” property-rights tradition and a pioneer in the theory of the firm, Alchian wrote on a dizzying variety of topics and was consistently insightful and original.

Alchian was very intellectually curious, always pushing in new directions and looking for new understandings, without much concern for his reputation or legacy. One personal story: I once asked him, as a naive and somewhat cocky junior scholar, how he reconciled the team-production theory of the firm in Alchian and Demsetz (1972) with the holdup theory in Klein, Crawford, and Alchian (1978). Aren’t these inconsistent? He replied — politely masking the irritation he must have felt — “Well, Harold came to me with this interesting problem to solve, and we worked up an explanation, and then, a few years later, Ben was working on a different problem, and we started talking about it….” In other words, he wasn’t thinking of developing and branding an “Alchian Theory of the Firm.” He was just trying to do interesting work.

Updates: Comments, remembrances, resources, links, etc.:

- Robert Higgs

- David Henderson (1, 2)

- Jerry O’Driscoll

- Alex Tabarrok

- Doug Allen

- Dan Benjamin

- A 1996 Alchian symposium (gated)

- Alchian and Woodward’s review of Williamson (1985): “The Firm Is Dead, Long Live the Firm”

New Review Paper on Multinational Firms

| Peter Klein |

The econ and strategy literatures on multinational firms have grown dramatically since the pioneering works of Caves, Casson, Teece, and others. Besides established journals like the Journal of International Economics and Journal of International Business Studies, there is the new Global Strategy Journal and plenty of space in the general-interest journals for issues dealing with multinationals.

Pol Antràs and Stephen Yeaple have written a new survey paper for the Handbook of International Economics, 4th edition, and it’s available as a NBER working paper, “Multinational Firms and the Structure of International Trade.” The review focuses on the mainstream economics literature but should be useful for management and organization scholars as well — particularly section 7 on firm boundaries which includes both transaction cost and property rights theories. Here’s the abstract:

This article reviews the state of the international trade literature on multinational firms. This literature addresses three main questions. First, why do some firms operate in more than one country while others do not? Second, what determines in which countries production facilities are located? Finally, why do firms own foreign facilities rather than simply contract with local producers or distributors? We organize our exposition of the trade literature on multinational firms around the workhorse monopolistic competition model with constant-elasticity-of-substitution (CES) preferences. On the theoretical side, we review alternative ways to introduce multinational activity into this unifying framework, illustrating some key mechanisms emphasized in the literature. On the empirical side, we discuss the key studies and provide updated empirical results and further robustness tests using new sources of data.

The NBER version is gated but I’m sure our intrepid readers can dig up an open-access copy.

Arrunada Seminar: Benito Arruñada – Underprovision of Public Registries?

| Benito Arruñada |

Underprovision of Public Registries?

Organizing registries is harder than it seems. Governments struggled for almost ten centuries to organize reliable registries that could make enabling rules safely applicable to real property. Similarly, company registries were adopted by most governments only in the nineteenth century, after the Industrial Revolution. Moreover, though most countries have now been running property and company registries for more than a century, only a few have succeeded in making them fully functional: in most countries, adding a mortgage guarantee to a loan does not significantly reduce its interest rate.

US registries show that these difficulties do not only affect developing countries. Many US registries are stunted, shaky institutions whose functions are partly provided by private palliatives. In land, the public county record offices have been unable to keep up with market demands for speed and uniform legal assurance. Palliative solutions such as title insurance duplicate costs only to provide incomplete in personam guarantees or even multiply costs, as Mortgage Electronic Registry Systems (MERS) did by being unable to safely and comprehensively record mortgage loan assignments. In company registries, their lack of ownership information means that they are of little help in fighting fraud, and their sparse legal review implies that US transactions require more extensive legal opinions. In patents, a speed-oriented US Patent and Trademark Office combines with a strongly motivated patent bar to cause an upsurge of litigation of arguably dangerous consequences for innovation.

The introduction of registries has often been protracted because part of the benefits of registering accrue to others. They also have to compete with private producers of palliative services (i.e., documentary formalization by lawyers and notaries) who usually prefer weak or dysfunctional registries, as they increase the demand for their services. Moreover, most legal resources, including the human capital of judges, scholars, and practitioners is adapted to personal instead of impersonal and registry-mediated exchange.

Information and communication technologies have opened new possibilities for impersonal trade, thus increasing the demand for the institutions, such as registries, that support impersonal trade. Economic development therefore hinges, more than ever, on governments’ ability to overcome these difficulties, which are allegedly holding back the effective registries needed to enable impersonal exchange and exhaust trade opportunities.

Arrunada Seminar: Corrado Malberti – What could be the next steps in the elaboration of a general theory of public registers?

| Corrado Malberti |

What could be the next steps in the elaboration of a general theory of public registers?

From a lawyer’s perspective, one of the most important contributions of Arruñada’s Institutional Foundations of Impersonal Exchange is the creation of a general economic theory on public registers. Even if this work is principally focused on business registers and on registers concerning immovable property, many of the results professor Arruñada achieves could be easily extended to other registers already existing in many legal systems or at the transnational level.

For example, a first extension of the theories proposed by professor Arruñada could be made by examining the functioning of the registers that collect information on the status and capacity of persons. A second field that should probably benefit from professor Arruñada’s achievements is that of public registers that operate at a transnational level and established by international treaties. In particular, in this second case, the reference is obviously to the Cape Town convention on International Interests in Mobile Equipment which will, and — to some extent — already has, resulted in the creation of different registers for the registrations of security interests for Aircrafts, Railway Rolling Stock, and Space Assets. In my view it will be important to test in what measure the solutions adopted for these registers are consistent with the results of Arruñada’s analysis.

Corrado Malberti, Professor in Commercial Law. University of Luxembourg. Commissione Studi Consiglio Nazionale del Notariato.

Does Boeing Have an Outsourcing Problem?

| Peter Klein |

Jim Surowiecki is a good business writer (and my college classmate) and I always learn from his essays (and his 2004 book The Wisdom of Crowds). But I think he gets it wrong on the Boeing 787 case. Jim echoes what is becoming the conventional management wisdom on the Dreamliner, namely that it’s long list of woes (the current battery problem being only the most recent) results from the decision to outsource most of the plane’s production. “The Dreamliner was supposed to become famous for its revolutionary design. Instead, it’s become an object lesson in how not to build an airplane.” Specifically:

[T]he Dreamliner’s advocates came up with a development strategy that was supposed to be cheaper and quicker than the traditional approach: outsourcing. And Boeing didn’t outsource just the manufacturing of parts; it turned over the design, the engineering, and the manufacture of entire sections of the plane to some fifty “strategic partners.” Boeing itself ended up building less than forty per cent of the plane.

This strategy was trumpeted as a reinvention of manufacturing. But while the finance guys loved it — since it meant that Boeing had to put up less money — it was a huge headache for the engineers. . . . The more complex a supply chain, the more chances there are for something to go wrong, and Boeing had far less control than it would have if more of the operation had been in-house.

The assumption here is that vertical integration is better for quality control and for coordinating complex production systems. But that assumption is just plain wrong. As the property-rights approach to the firm has emphasized, control and coordination problems occur in internal as well as external contracting. As Thomas Hubbard points out,

The more modern thinking about procurement emphasizes that this problem appears — albeit in different forms — both when a company procures internally and when it subcontracts. The problem of getting procurement incentives right does not disappear when you produce internally rather than subcontract; it just changes. Companies struggle to get their subcontractors to produce what they want at low cost; they also struggle to get their own divisions to do so.

In other words, Boeing might have had the same problems with in-house production. “It is certainly possible that the Dreamliner’s current problems are derived from its design — it relies far more on electrical systems than Boeing’s previous planes — and that these problems would have been just as significant (and worse on the cost front) had Boeing sourced more sub-assemblies internally.” Hubbard’s essay includes a number of additional insights derived from modern theories of the firm, such as the Williamsonian idea that adaptation is the central issue distinguishing markets from hierarchies.

So, the next time you read that firms should vertically integrate to maintain quality, as yourself, are employees always easier to control than subcontractors?

The Myth of the Flattening Hierarchy

| Peter Klein |

We’ve written many posts on the popular belief that information technology, globalization, deregulation, and the like have rendered the corporate hierarchy obsolete, or at least led to a substantial “flattening” of the modern corporation (see the links here). The theory is all wrong — these environmental changes affect the costs of both internal and external governance, and the net effect on firm size and structure are ambiguous — and the data don’t support a general trend toward smaller and flatter firms.

Julie Wulf has a paper in the Fall 2012 California Management Review summarizing her careful and detailed empirical work on the shape of corporate hierarchies. (The published version is paywalled, but here is a free version.) Writes Julie:

I set out to investigate the flattening phenomenon using a variety of methods, including quantitative analysis of large datasets and more qualitative research in the field involving executive interviews and a survey on executive time use. . . .

We discovered that flattening has occurred, but it is not what it is widely assumed to be. In line with the conventional view of flattening, we find that CEOs eliminated layers in the management ranks, broadened their spans of control, and changed pay structures in ways suggesting some decisions were in fact delegated to lower levels. But, using multiple methods of analysis, we find other evidence sharply at odds with the prevailing view of flattening. In fact, flattened firms exhibited more control and decision-making at the top. Not only did CEOs centralize more functions, such that a greater number of functional managers (e.g., CFO, Chief Human Resource Officer, CIO) reported directly to them; firms also paid lower-level division managers less when functional managers joined the top team, suggesting more decisions at the top. Furthermore, CEOs report in interviews that they flattened to “get closer to the businesses” and become more involved, not less, in internal operations. Finally, our analysis of CEO time use indicates that CEOs of flattened firms allocate more time to internal interactions. Taken together, the evidence suggests that flattening transferred some decision rights from lower-level division managers to functional managers at the top. And flattening is associated with increased CEO involvement with direct reports —the second level of top management—suggesting a more hands-on CEO at the pinnacle of the hierarchy.

As they say, read the whole thing.

Arrunada Seminar: Matteo Rizzolli – Will ICT Make Registries Irrelevant?

| Matteo Rizzolli |

Will ICT Make Registries Irrelevant?

With this brief post, I would like to add some further discussion on the role of new technologies and ICTs for the evolution of registries. The book of Prof Arrunada touches upon the issue in chapter 7 where the role of technical chance is tackled. He discusses mainly the challenges in implementing different degrees of automation in pre-compiling and lodging information from interested parties and even in automating decision-making by the registry itself.

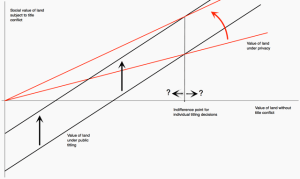

These challenges represent the costs of introducing ICTs in registries. In the book the benefits of ICTs for abating the costs of titling/recording are not discussed at length. Think of them in terms of the costs of gathering, entering, storing, organising and searching the data. I assume it is trivial to say that ICTs decrease the fixed and variable costs of registries even when some issues raised in the book are considered. In terms of the figure below (my elaboration of figure 5.1 on pg 133) this is equivalent to say that, thanks to ICTs, the black line representing the “Value of land under public titling” shifts upwards and therefore the “Indifference point for individual titling decisions” shifts leftward and makes registries more desirable.

However, i think that an important effect of ICTs is neglected in this analysis. In fact ICTs are now pervasive in most transactions. Land is observed with all sorts of satellite technology and the movement of objects and people is traced in many ways. Communications, both formal and informal are also traced and information on companies is just one click away for most individuals. I don’t want to discuss philosophical, sociological or legal aspects of this information bonanza. Neither neglect that more information doesn’t mean better or more trustworthy information. On the other I think we can agree that the quantity of information available to counterparts of a transaction is greatly increased and -more important- that verifiable evidence can be produced more easily should legal intervention in case of conflict arise.

All this information windfall may -this is my hypothesis- decrease the costs of keeping transactions out of registries and therefore improve the value of transactions under privacy. In terms of the figure below, this amounts to rotating the red line upwards and, as a result, shifting the “Indifference point for individual titling decisions” on the right.

In a sense, ICTs both i) decrease the costs of registries and ii) makes registries less relevant. On balance, it is hard for me to say which effect of ICTs may prevail. I think however this could be a very interesting empirical question to research.

Matteo Rizzolli. Assistant Professor of Law and Economics at the Free University of Bozen, Italy. Board member and secretary of the European Law & Economics Association

Click figure for higher resulution:

Arrunada Seminar: Rod Thomas – Developing a Credible Automated System for Agency Registration under a “Registration of Rights” Model

| Rod Thomas |

Developing a Credible Automated System for Agency Registration under a “Registration of Rights” Model

In his book, Arruñada rehearses the debate between mere recordation of deeds versus registration of rights. Under the “registration of rights” model, the registration event may be backed by a State guarantee of ownership, as is the case under a Torrens system. Under such a system, the need for a credible automated system is paramount. This is because the registration event is normally conclusive as to title rights, even in the face of third party ineptness or fraud in undertaking the registration. By way of example, in Torrens systems, the transaction, once completed, can conventionally only be overturned where the transferee is found to have been fraudulent in obtaining the registered title interest even if the dealing is void at law.

Under a registration of rights model there is a heightened sense of vulnerability where the registration even is undertaken by an agent. This is because the agent and not the transferee may have been either fraudulent or inept in undertaking the transaction. An example of such a system in operation is the Landonline System, as it presently exists in New Zealand, where only agency registration is possible.

Arruñada also argues that for a registration system to be successful, it needs to be both cost effective and accessible. Consequently a tension arises under a registration of rights model, operated by agency registration. On the one hand effective measures need to be put in place to protect consumers from inept or fraudulent transactions. On the other hand, a system which is overly complex, or expensive to operate, is unlikely to be successful.

Such concerns may be less pressing in countries where digitalised signatures already play a key role in authorising transactions. In those jurisdictions it appears to be a relatively straightforward procedure to incorporate the need for the existing interest holder’s digitalised signature before a transaction can occur. What however of jurisdictions such as the United Kingdom, Australia or New Zealand where digitalised signatures are not in ready use and agency registration is common?

Various possibilities come to mind for these other jurisdictions. One may be imposing a system where each dealing must first be authorised by a private PIN number known only to the existing land interest holder. This however may be cumbersome to operate and regulate. Also, PIN number may not be securely kept, so abuses could still occur. Another possibility may be to incorporate “flags” into the automated system, so the interest holder is notified of any proposed dealing with his or her interest, and can therefore block the proposed registration before it occurs.

The question therefore needs to be asked; “what possibilities exist under a registration of rights model (in the absence of electronic signatures) for setting up a safe and cost effective automated system, operated by agency registration?”

Rod Thomas. Senior Lecturer in Law, Auckland University of Technology, New Zealand

Handbook of Organizational Economics

| Peter Klein |

It’s edited by Bob Gibbons and John Roberts, just published by Princeton, and you can read about it here, including the table of contents and the introduction. As Gibbons and Roberts note:

Organizational economics involves the use of economic logic and methods to understand the existence, nature, design, and performance of organizations, especially managed ones. As this handbook documents, economists working on organizational issues have now generated a large volume of exciting research, both theoretical and empirical. However, organizational economics is not yet a fully recognized field in economics — for example, it has no Journal of Economic Literature classification number, and few doctoral programs offer courses in it. The intent of this handbook is to make the existing research in organizational economics more accessible to economists and thereby to promote further research and teaching in the field.

This is a fair assessment, though some O&M readers may find the editors’ definition of the field too narrow. The volume covers a wide variety of issues, topics, and applications but nearly all from the perspective of modern neoclassical economics (there’s a chapter on TCE by Williamson and Steve Tadelis, but nothing on “old” property rights theory, capabilities, the knowledge-based view, etc.). Still, it appears to be an excellent collection of state-of-the-art papers. Besides the usual topics like incentives, authority, complementarity, innovation, ownership, vertical integration, and the like, there’s also an interesting methodological section featuring “Clinical Papers in Organizational Economics” by George Baker and Ricard Gil, “Experimental Organizational Economics” by Colin Camerer and RobertoWeber, and “Insider Econometrics by Casey Ichniowski and Kathy Shaw. Check it out.

Arrunada Seminar: Stephen Hansen – Public Institutions and Endogenous Information in Contracting

| Stephen Hansen |

Public Institutions and Endogenous Information in Contracting

Benito Arruñada’s Institutional Foundations of Impersonal Exchange: Theory and Policy of Contractual Registries is an impressive and erudite study of the relationship between legal institutions and impersonal exchange. While clearly valuable for better understanding policies regarding formalization, in my mind it also introduces ideas that are relevant for contract theory more generally and yet hardly treated in the literature.

Since the 1970’s economic theorists have understood that information asymmetries between parties who write contracts are a key source of inefficiencies in exchange. Since then, a vast literature has developed exploring this idea from many different angles. Nevertheless, two key features usually appear. First, the set of parties who write contracts all observe each other, know they are contracting with each other, and (with some exceptions) observe the terms of the contracts agreed. Second, the information asymmetries are assumed to be a fixed, exogenous feature of relationships.

Benito’s book convincingly shows that both of these limit our understanding of trading frictions in the real world. A key insight is that, in addition to his “type” or “action” (to use the language of contract theory), the formal contracts that an economic agent has written with others may be unobservable. After reading the book, it became clear to me that this dimension of non-observability is just as important for generating market failure as others. The second, and intimately related, insight is that the degree of non-observability of contractual rights depends on public institutions, in particular registration systems. Whereas it is unclear how a public body would help contracting parties discover — to take a standard example — each other’s preferences over the good they are proposing to trade, Benito shows that they can affect the amount of information they have about each other’s formal legal rights. And, in line with what one would expect, when institutions can reduce this information asymmetry, the likelihood of efficient trades increases.

Putting these two ideas together provides an original and to me very exciting view on the value of legal systems. Economists often discuss “good” legal systems as those which enforce written agreements transparently at low cost. After reading Benito’s book, I recognized that legal systems also act to endogenously affect the amount of information that parties have available to reach those agreements in the first place. This deserves to be an influential idea in future discussions of law, economics, and contract theory.

Stephen Hansen. Assistant Professor. Economics Department. Universitat Pompeu Fabra. Barcelona, Spain

Arrunada Seminar: Corrado Malberti (2) – An Empirical Test on the Differences between Recordation and Registration

| Corrado Malberti |

An Empirical Test on the Differences between Recordation and Registration

One key point of professor Arruñada is that “[i]t is safe to assume that recordation is less effective than registration in avoiding title uncertainty”. However, the Author acknowledges that it would be essential to perform some empirical analysis to support his conclusions. Importantly he also acknowledges that comparing the performance of titling systems is a daunting task, and that it should be important to consider the specifics of each country.

To start the debate on this point, professor Arruñada compares simple averages for two samples of European Union countries with different titling systems. The Author discovers that, apparently (at least in Europe), registration systems are not only more effective, but also less costly than recordation systems. However, Arruñada also acknowledges that this data is more a starting point for a fruitful discussion than the end of the debate, since it would be ”premature . . . to interpret these empirical differences as causal effects, given the small samples involved”.

I completely agree with this perspective and, I also believe that, starting from this data, it will be important to further investigate the matter.

However, this also poses the question on which is the direction empirical research should take in future. In fact, it is conventional wisdom among legal scholars that registration is superior to recordation. For example, it was also for that reason that, after the end of WWI, Italy decided to preserve in the new provinces the registration system already in place in Austria-Hungary, and that France decided to maintain the livre foncier in Alsace-Moselle.

Since any generalization concerning the classifications of public registers may have little predictive value on how real legal problems are solved, probably, in future, it will be prudent to carry out empirical analyses that consider homogeneous legal frameworks. This would limit the risks of giving the same label to systems that practically adjudicate disputes in completely different ways. Thus, from this perspective, it would probably be more interesting and valuable to focus the attention on those legal systems, like the French and the Italian, where two different public registers coexist.

Corrado Malberti, Professor in Commercial Law. University of Luxembourg. Commissione Studi Consiglio Nazionale del Notariato.

Recent Comments