Rational Inattention

| Dick Langlois |

The idea of attention as a scarce resource goes back at least to Herbert Simon and Nelson and Winter. I hadn’t seen much application of this idea in a while until I ran across this interesting paper called “Rational Inattention and Organizational Focus” by Wouter Dessein, Andrea Galeotti, and Tano Santos. Here’s the abstract:

We examine the allocation of scarce attention in team production. Each team member is in charge of a specialized task, which must be adapted to a privately observed shock and coordinated with other tasks. Coordination requires that agents pay attention to each other, but attention is in limited supply. We show how organizational focus and leadership naturally arise as the result of a fundamental complementarity between the attention devoted to an agent and the amount of initiative taken by that agent. At the optimum, all attention is evenly allocated to a select number of “leaders”. The organization then excels in a small number of focal tasks at the expense of all others. Our results shed light on the importance of leadership, strategy and “core competences” in team production, as well as new trends in organization design. We also derive implications for the optimal size or “scope” of organizations: a more variable environment results in smaller organizations with more leaders. Surprisingly, improvements in communication technology may also result in smaller but more balanced and adaptive organizations.

Apparently, Dessein has been working on attention models for some time, though I hadn’t noticed. (But, of course, Peter had.) I should also note that this model is similar in spirit to the work of Sharon Gifford, now 20 years old, which Dessein et al. do not cite.

Coasean Bargaining Opportunity

| Peter Klein |

Forget Wrigley Field: here’s a colorful example for classroom discussions of property rights, external costs, bargaining, and the Coase Theorem. Literally colorful. (Via Bob Subrick.)

Incomplete Contracts and the Internal Organization of Firms

| Peter Klein |

That’s the title of a new NBER paper by Philippe Aghion, Nicholas Bloom, and John Van Reenen, indicating that organization design, from the perspective of incomplete-contracting theory, continues to be a hot topic among the top economists. Like all NBER papers this one is gated, but intrepid readers may be able to locate a freebie.

Incomplete Contracts and the Internal Organization of Firms

Philippe Aghion, Nicholas Bloom, John Van ReenenNBER Working Paper No. 18842, February 2013

We survey the theoretical and empirical literature on decentralization within firms. We first discuss how the concept of incomplete contracts shapes our views about the organization of decision-making within firms. We then overview the empirical evidence on the determinants of decentralization and on the effects of decentralization on firm performance. A number of factors highlighted in the theory are shown to be important in accounting for delegation, such as heterogeneity and congruence of preferences as proxied by trust. Empirically, competition, human capital and IT also appear to foster decentralization. There are substantial gaps between theoretical and empirical work and we suggest avenues for future research in bridging this gap.

Trento Summer School on Modularity

| Dick Langlois |

This summer I am directing a two-week summer school on “Modularity and Design for Innovation,” July 1-12. I am working closely with Carliss Baldwin, who will be the featured speaker. Other guest speakers will include Stefano Brusoni, Annabelle Gawer, Luigi Marengo, and Jason Woodard.

The school is intended for Ph.D. students, post-docs, and newly minted researchers in technology and operations management, strategy, finance, and the economics of organizations and institutions. The school provides meals and accommodations at the beautiful Hotel Villa Madruzzo outside Trento. Students have to provide their own travel. More information and application here.

This is the fourteenth in a series of summer schools organized at Trento by Enrico Zaninotto and Axel Leijonhufvud. In 2004, I directed one on institutional economics.

I, Coke Can

| Peter Klein |

| Peter Klein |

Via Craig Newmark, a modern riff on Leonard Read’s classic:

The number of individuals who know how to make a can of Coke is zero. The number of individual nations that could produce a can of Coke is zero. This famously American product is not American at all. Invention and creation is something we are all in together. Modern tool chains are so long and complex that they bind us into one people and one planet. They are not only chains of tools, they are also chains of minds: local and foreign, ancient and modern, living and dead — the result of disparate invention and intelligence distributed over time and space. Coca-Cola did not teach the world to sing, no matter what its commercials suggest, yet every can of Coke contains humanity’s choir.

No surprises here to students of open innovation, but a vivid illustration nonetheless.

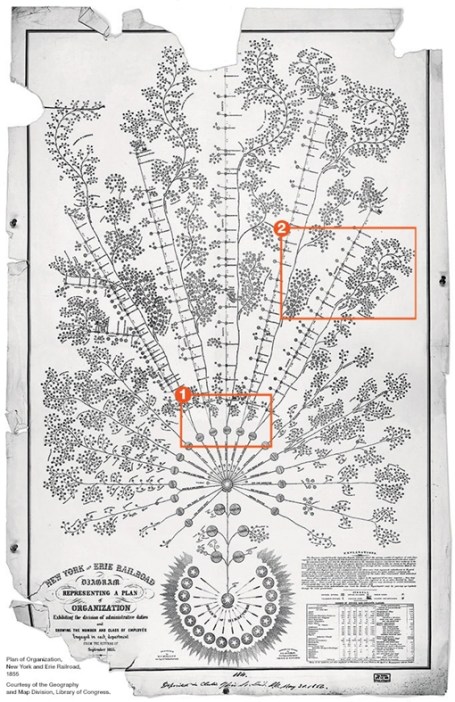

The First Modern Organizational Chart

| Peter Klein |

It was designed in 1854 for the New York and Erie Railroad and reflects a highly decentralized structure, with operational decisions concentrated at the local level. McKinsey’s Caitlin Rosenthal describes it as an early attempt to grapple with “big data,” one of today’s favored buzzwords. See her article, “Big Data in the Age of the Telegraph,” for a fascinating discussion. And remember, there’s little new under the sun (1, 2, 3).

Sequestration and the Death of Mainstream Journalism

| Peter Klein |

Much virtual ink has been spilled over the decline of the mainstream media, measured by circulation, advertising revenue, or a general sense of irrelevance. Usual explanations relate to the changing economics of news gathering and publication, the growth of social media, demographic and cultural shifts, and the like. These are all important but the main issue, I believe, is the characteristics of the product itself. Specifically, news consumers increasingly recognize that the mainstream media outlets are basically public relations services for government agencies, large companies, and other influential organizations. Journalists do very little actual journalism — independent investigation, analysis, reporting. They are told what stories are “important” and, for each story, there is an official Narrative, explaining the key issues and acceptable opinions on these issues. Journalists’ primary sources are off-the-record, anonymous briefings by government officials or other insiders, who provide the Narrative. A news outlet that deviates from the Narrative by doing its own investigation or offering its own interpretation risks being cut off from the flow of anonymous briefings (and, potentially, excluded from the White House Press Corps and similar groups), which means a loss of prestige and a lower status. Basically, the mainstream news outlets offer their readers a neatly packaged summary of the politically correct positions on various issues. In exchange for sticking to the Narrative, they get access to official sources. Give up one, you lose the other. Readers are beginning to recognize this, and they don’t want to pay.

Nowhere is this situation more apparent than the mainstream reporting on budget sequestration. The Narrative is that sequestration imposes large and dangerous cuts — $85 billion, a Really Big Number! — to essential government services, and that the public reaction should be outrage at the President and Congress (mostly Congressional Republicans) for failing to “cut a deal.” You can picture the reporters and editors grabbing their thesauruses to find the right words to describe the cuts — “sweeping,” “drastic,” “draconian,” “devastating.” In virtually none of these stories will you find any basic facts about the budget, which are easily found on the CBO’s website, e.g.:

- Sequestration reduces the rate of increase in federal spending. It does not cut a penny of actual (nominal) spending.

- The CBO’s estimate of the reduction in increased spending between 2012 and 2013 is $43 billion, not $85 billion.

- Total federal spending in 2012 was $3.53 trillion. The President’s budget request for 2013 was $3.59 trillion, an increase of $68 billion (about 2%). Under sequestration, total federal spending in 2013 will be $3.55 trillion, an increase of only $25 billion (a little less than 1%).

- Did you catch that? Under sequestration, total federal spending goes up, just by less than it would have gone up without sequestration. This is what the Narrative calls a “cut” in spending! It’s as if you asked your boss for a 10% raise, and got only a 5% raise, then told your friends you got a 5% pay cut.

- Of course, these are nominal figures. In real terms, expenditures could go down, depending on the rate of inflation. Even so, the cuts would be tiny — 1 or 2%.

- The news media also talk a lot about “debt reduction,” but what they mean is a reduction in the rate at which the debt increases. Even with sequestration, there is a projected budget deficit — the government will spend more than it takes in — during every year until 2023, the last year of the CBO estimates. The Narrative grudgingly admits that sequestration might be necessary to reduce the national debt, but sequestration doesn’t even do that. It’s as if you went on a “dramatic” weight-loss plan by gaining 5 pounds every year instead of 10.

This is all public information, easily accessible from the usual places. But mainstream news reporters can’t be bothered to look is up, and don’t feel any need to, because they have the Narrative, which tells them what to say. Seriously, have you read anything in the New York Times, Washington Post, or Wall Street Journal or heard anything on CNN or MSNBC clarifying that the “cuts” are reductions in the rate of increase? Even Wikipedia, much maligned by the establishment media, gets it right: ” sequestration refers to across the board reductions to the planned increases in federal spending that began on March 1, 2013.” If we have Wikipedia, why on earth would we pay for expensive government PR firms?

NB: See also earlier comments on the mainstream media here and here.

Russian Summer School on Institutional Analysis

| Peter Klein |

The Center for Institutional Studies at Russia’s Higher School of Economics sponsors an annual summer school “aimed at creating and supporting the academic network of young researchers from all regions of Russia as well as from CIS and other countries, who work in the field of New Institutional Economics.” This year’s conference is 29 June – 5 July in Moscow, and the faculty includes former O&M guest blogger Scott Masten along with John Nye, Russell Pittman, Garrett Jones, and many others. The full program, along with registration and other info, is available at the conference site.

My Response to Shane (2012)

| Peter Klein |

Peter Lewin blogged earlier on the ten-year retrospectives by Scott Shane and Venkataraman et al. on the influential 2000 Shane and Venkataraman paper, “The Promise of Entrepreneurship as a Field of Research.” As Peter mentioned, Shane acknowledges critics of the opportunity construct such as Sharon Alvarez, Jay Barney, Per Davidsson, and me, but dismisses our concerns as trivial or irrelevant.

The January 2013 issue of AMR includes a formal response by Alvarez and Barney, as well as rejoinders by Shane (with Jon Eckhardt) and Venkataraman (with Saras Sarasvathy, Nick Dew, and William Forster). The dialogue is well worth reading. I didn’t participate in the symposium but do have a brief response to Shane.

My critique of Shane’s work, and the opportunity-discovery perspective more generally, is that the scientific understanding of entrepreneurship has been held back by the focus on opportunities. The basic idea is simple: “opportunities” do not exist objectively, but are only only subjective images, or conjectures, about future possibilities. They exist in the mind of the entrepreneur, who takes actions to try to bring them about. The very concept of opportunity makes sense only ex post, after actions have been taken and future outcomes realized, leading to realized profits and losses. Under uncertainty, there are no opportunities, only entrepreneurial forecasts, which may turn out to be correct or incorrect. (My critique is slightly different from that of Alvarez and Barney, who argue that some opportunities are “discovered,” but others are “created.” My position is that the whole idea of opportunity is at best redundant, and at worst misleading and harmful.) I maintain that the unit of analysis in entrepreneurship research should be action (investment) under uncertainty, not the discovery (or creation) of profit opportunities.

These arguments are laid out in my 2008 SEJ article and in the Foss-Klein 2012 book. They also came to the fore in a recent exchange with Israel Kirzner, the intellectual father of the opportunity construct. (more…)

Doug Allen on Alchian

| Peter Klein |

A remembrance from our friend Doug Allen:

I only met Armen once, but his influence on me was profound. In the fall of 1980 I was taking intermediate micro economics to fulfill a Business Degree requirement. The course was taught by the great Art DeVany, who had been a student of Armen’s at UCLA. Naturally he used “Exchange and Production” as his text. I remember vividly the day — it was a Thursday, late on a cloudy afternoon — when I entered a corner of a large hallway on campus. I was thinking about the concept covered in class that week: “prices are not determined by costs.” I went into that corner thinking like an accountant, and when I came out the other side I was thinking like an economist. It was an epiphany. I came out thinking “of course prices are not determined by costs!”

I quickly changed majors, decided to postpone law school for a detour in graduate economics, and have never looked back. Fortunately for me my advanced undergraduate theory class was taught by Chris Hall, an intellectual grandson of Armen’s via Steve Cheung. His text for the course was “Economic Forces at Work.” I loved Armen’s writing, his style, and his ease in making life a big puzzle to solve.

I mentioned that I have only met the great man once. It was at a PERC conference in the early 1990s. The small group sat around tables in alphabetical order, and so Alchian was first and (Doug) Allen was second. I jokingly said “ah, Alchain and Allen, together again.” I thought it was quite witty, but Armen ignored the remark. I made some other comments that he was similarly impressed with. So, remembering that “even a fool is counted wise when he keeps his mouth shut,” I just sat back and listened. It was a great treat, and Armen didn’t seem to mind having me tag along for the weekend. My favorite recollection was a long discussion we had over how Rockefeller actually made money.

As I think about his passing, the one thought that strikes me is “where is the Armen Alchain for today?” Where is the economist’s economist? I suppose there just never will be another AAA.

Armen Alchian (1914-2013)

| Peter Klein |

Armen Alchian passed away this morning at 98. We’ll have more to write soon, but note for now that Alchian is one of the most-often discussed scholars here at O&M. A father of the “UCLA” property-rights tradition and a pioneer in the theory of the firm, Alchian wrote on a dizzying variety of topics and was consistently insightful and original.

Alchian was very intellectually curious, always pushing in new directions and looking for new understandings, without much concern for his reputation or legacy. One personal story: I once asked him, as a naive and somewhat cocky junior scholar, how he reconciled the team-production theory of the firm in Alchian and Demsetz (1972) with the holdup theory in Klein, Crawford, and Alchian (1978). Aren’t these inconsistent? He replied — politely masking the irritation he must have felt — “Well, Harold came to me with this interesting problem to solve, and we worked up an explanation, and then, a few years later, Ben was working on a different problem, and we started talking about it….” In other words, he wasn’t thinking of developing and branding an “Alchian Theory of the Firm.” He was just trying to do interesting work.

Updates: Comments, remembrances, resources, links, etc.:

- Robert Higgs

- David Henderson (1, 2)

- Jerry O’Driscoll

- Alex Tabarrok

- Doug Allen

- Dan Benjamin

- A 1996 Alchian symposium (gated)

- Alchian and Woodward’s review of Williamson (1985): “The Firm Is Dead, Long Live the Firm”

Entrepreneurship and Knowledge

| Peter Klein |

Hayek famously argued that prices embody information and that economic actors, responding to price changes, act as if they knew the underlying circumstances generating these changes. “[I]n a system in which the knowledge of the relevant facts is dispersed among many people, prices can act to coordinate the separate actions of different people in the same way as subjective values help the individual to coordinate the parts of his plan.” To economize, people don’t need “knowledge of the particular circumstances of time and place,” they only need access to prices. “The mere fact that there is one price for any commodity . . . brings about the solution which (it is just conceptually possible) might have been arrived at by one single mind possessing all the information which is in fact dispersed among all the people involved in the process.” Hayek illustrates with his famous example of the tin market: “All that the users of tin need to know is that some of the tin they used to consume is now more profitably employed elsewhere and that, in consequence, they must economize tin. There is no need for the great majority of them even to know where the more urgent need has arisen, or in favor of what other needs they ought to husband the supply.”

Hayek offers a powerful argument against interference with the price mechanism. But we should remember that prices embody information about the past, and the entrepreneur’s job is to anticipate, or “appraise,” the future. Entrepreneurs, far from discovering and exploiting “gaps” in the existing structure of prices, deploy resources in anticipation of expected — but uncertain — profits generated by future prices. For this, they rely on what Mises called a “specific anticipative understanding of the conditions of the uncertain future,” an understanding that requires a lot of knowledge of particular circumstances of time and place!

The knowledge requirements of the successful entrepreneur or arbitrageur are vividly illustrated in this passage from Carsten Jensen’s magnificent novel, We the Drowned, in a passage about 19th-century ship brokers, entrepreneurs who own, lease, and manage ships and shipping contracts:

A ship broker needs to know how the Russo-Japanese War will hit the freight market. He doesn’t need to be interested in politics, but he has to pay attention to his skippers’ finances, so a knowledge of international conflict is essential. Opening up a newspaper — he’ll see a photograph of a head of state and if he’s bright enough, he’ll read his own future profits in the man’s face. He might not he interested in socialism, in fact he’ll swear he isn’t: he’s never heard such a load of starry-eyed nonsense. Until one day his crew lines up and demands higher wages, and he has to immerse himself in union issues and other newfangled notions about the future organization of society. A broker must keep up to date with the names of foreign heads of state, the political currents of the time, the various enmities between nations, and earthquakes in distant parts of the world. He makes money out of wars and disasters, but first and foremost he makes it because the world has become one big building site. Technology rearranges everything, and he needs to know its secrets, its latest inventions and discoveries. Saltpeter, divi-divi, soy cakes, pit props, soda, dyer’s broom — these aren’t just names to him. He’s neither touched saltpeter nor seen a swatch of dyer’s broom. He’s never tasted soy cake (for which he can count himself lucky), but he knows what it’s used for and where there’s a demand for it. He doesn’t want the world to stop changing. If it did, his office would have to close. He knows what a sailor is: an indispensable helper in the great workshop that technology has made of the world.

There was a time when all we ever carried was grain. We bought it in one place and sold it in another. Now we were circumnavigating the globe with a hold full of commodities whose names we had to learn to pronounce and whose use had to be explained to us. Our ships had become our schools. They were still powered by the wind in their sails, as they had been for thousands of years. But stacked in their holds lay the future.

New Review Paper on Multinational Firms

| Peter Klein |

The econ and strategy literatures on multinational firms have grown dramatically since the pioneering works of Caves, Casson, Teece, and others. Besides established journals like the Journal of International Economics and Journal of International Business Studies, there is the new Global Strategy Journal and plenty of space in the general-interest journals for issues dealing with multinationals.

Pol Antràs and Stephen Yeaple have written a new survey paper for the Handbook of International Economics, 4th edition, and it’s available as a NBER working paper, “Multinational Firms and the Structure of International Trade.” The review focuses on the mainstream economics literature but should be useful for management and organization scholars as well — particularly section 7 on firm boundaries which includes both transaction cost and property rights theories. Here’s the abstract:

This article reviews the state of the international trade literature on multinational firms. This literature addresses three main questions. First, why do some firms operate in more than one country while others do not? Second, what determines in which countries production facilities are located? Finally, why do firms own foreign facilities rather than simply contract with local producers or distributors? We organize our exposition of the trade literature on multinational firms around the workhorse monopolistic competition model with constant-elasticity-of-substitution (CES) preferences. On the theoretical side, we review alternative ways to introduce multinational activity into this unifying framework, illustrating some key mechanisms emphasized in the literature. On the empirical side, we discuss the key studies and provide updated empirical results and further robustness tests using new sources of data.

The NBER version is gated but I’m sure our intrepid readers can dig up an open-access copy.

Hayek and Organizational Studies

| Peter Klein |

That’s the title of a new review paper by Nicolai and me for the forthcoming Oxford Handbook of Sociology, Social Theory, and Organizational Studies, edited by Paul Adler, Paul du Gay, Glenn Morgan, and Mike Reed (Oxford University Press, 2013). No, we haven’t gone over to the Dark Side (I mean, the good side), we just think Hayek’s work deserves to be better known among all scholars of organization, not only economists. Unlike many treatments of Hayek, we don’t focus exclusively, or even primarily, on tacit knowledge, but on capital theory, procedural rules, and other aspects of Hayek’s “Austrian” thinking.

You can download the paper at SSRN. Here’s the abstract:

We briefly survey Hayek’s work and argue for its increasing relevance for organizational scholars. Hayek’s work inspired aspects of the transaction cost approach to the firm as well as knowledge management and knowledge-based view of the firm. But Hayek is usually seen within organizational scholarship as a narrow, technical economist. We hope to change that perception here by pointing to his work on rules, evolution, entrepreneurship and other aspects of his wide-ranging oeuvre with substantive implications for organizational theory.

Arrunada Seminar: Benito Arruñada – Underprovision of Public Registries?

| Benito Arruñada |

Underprovision of Public Registries?

Organizing registries is harder than it seems. Governments struggled for almost ten centuries to organize reliable registries that could make enabling rules safely applicable to real property. Similarly, company registries were adopted by most governments only in the nineteenth century, after the Industrial Revolution. Moreover, though most countries have now been running property and company registries for more than a century, only a few have succeeded in making them fully functional: in most countries, adding a mortgage guarantee to a loan does not significantly reduce its interest rate.

US registries show that these difficulties do not only affect developing countries. Many US registries are stunted, shaky institutions whose functions are partly provided by private palliatives. In land, the public county record offices have been unable to keep up with market demands for speed and uniform legal assurance. Palliative solutions such as title insurance duplicate costs only to provide incomplete in personam guarantees or even multiply costs, as Mortgage Electronic Registry Systems (MERS) did by being unable to safely and comprehensively record mortgage loan assignments. In company registries, their lack of ownership information means that they are of little help in fighting fraud, and their sparse legal review implies that US transactions require more extensive legal opinions. In patents, a speed-oriented US Patent and Trademark Office combines with a strongly motivated patent bar to cause an upsurge of litigation of arguably dangerous consequences for innovation.

The introduction of registries has often been protracted because part of the benefits of registering accrue to others. They also have to compete with private producers of palliative services (i.e., documentary formalization by lawyers and notaries) who usually prefer weak or dysfunctional registries, as they increase the demand for their services. Moreover, most legal resources, including the human capital of judges, scholars, and practitioners is adapted to personal instead of impersonal and registry-mediated exchange.

Information and communication technologies have opened new possibilities for impersonal trade, thus increasing the demand for the institutions, such as registries, that support impersonal trade. Economic development therefore hinges, more than ever, on governments’ ability to overcome these difficulties, which are allegedly holding back the effective registries needed to enable impersonal exchange and exhaust trade opportunities.

Creativity and Property Rights

| Peter Klein |

I haven’t been following the Cato Unbound debate on US copyright law, but Adam Mossoff directs me to Mark Schultz’s post, “Where are the Creators? Consider Creators in Copyright Reform.” Mark thinks current debates over copyright law neglect the role of creativity: “Too often, the modern copyright debate overlooks the fact that copyright concerns creative works made by real people, and that the creation and commercialization of these works requires entrepreneurial risk taking. A debate that overlooks these facts is factually, morally, and economically deficient. Any reform that arises from such a context is likely to be both unjust and economically harmful.” Adam thinks Mark’s position “calls out the cramped, reductionist view of copyright policy that leads some libertarians and conservatives to castigate this property right as ‘regulation’ or as ‘monopoly.'”

As one of those libertarians critical of copyright law, but also an enthusiast for the fundamental creativity of the entrepreneurial act, let me respond briefly. Mark is certainly right that creative works are created by individuals (not, “discovered,” as some of the entrepreneurship literature might lead you to believe). But I don’t see the implications for copyright law. The legal issue is not the ontology of creative works, but the legal rights of others to use their own justly owned property in relation to these creative works. Copyright law is, after all, about delineating property rights, and whether legal protection should be extended to X does not follow directly from the fact that X was “created” instead of “discovered.”

Mark uses the language of entrepreneurship, and I think this argues against his conclusion. Property law protects the property of the entrepreneur, and the ventures he creates, not the stream of income accruing to those ventures. Suppose Mark has the brilliant insight to open a Brooklyn-style deli on a street corner here in Columbia, Missouri, makes lots of money, and then I open a similar shop across the street, cutting into his revenues. No one would argue that I’ve violated Mark’s property rights; the law rightly protects the physical integrity of Mark’s shop, such that I can’t break in and steal his equipment, but doesn’t protect him against pecuniary externalities. The fact that Mark’s restaurant wouldn’t have existed if he hadn’t created it — that “real people make this stuff,” as he puts it — has no bearing on the legality of my opening up a competing restaurant, even though this harms him economically.

Arrunada Seminar: Corrado Malberti – What could be the next steps in the elaboration of a general theory of public registers?

| Corrado Malberti |

What could be the next steps in the elaboration of a general theory of public registers?

From a lawyer’s perspective, one of the most important contributions of Arruñada’s Institutional Foundations of Impersonal Exchange is the creation of a general economic theory on public registers. Even if this work is principally focused on business registers and on registers concerning immovable property, many of the results professor Arruñada achieves could be easily extended to other registers already existing in many legal systems or at the transnational level.

For example, a first extension of the theories proposed by professor Arruñada could be made by examining the functioning of the registers that collect information on the status and capacity of persons. A second field that should probably benefit from professor Arruñada’s achievements is that of public registers that operate at a transnational level and established by international treaties. In particular, in this second case, the reference is obviously to the Cape Town convention on International Interests in Mobile Equipment which will, and — to some extent — already has, resulted in the creation of different registers for the registrations of security interests for Aircrafts, Railway Rolling Stock, and Space Assets. In my view it will be important to test in what measure the solutions adopted for these registers are consistent with the results of Arruñada’s analysis.

Corrado Malberti, Professor in Commercial Law. University of Luxembourg. Commissione Studi Consiglio Nazionale del Notariato.

Does Boeing Have an Outsourcing Problem?

| Peter Klein |

Jim Surowiecki is a good business writer (and my college classmate) and I always learn from his essays (and his 2004 book The Wisdom of Crowds). But I think he gets it wrong on the Boeing 787 case. Jim echoes what is becoming the conventional management wisdom on the Dreamliner, namely that it’s long list of woes (the current battery problem being only the most recent) results from the decision to outsource most of the plane’s production. “The Dreamliner was supposed to become famous for its revolutionary design. Instead, it’s become an object lesson in how not to build an airplane.” Specifically:

[T]he Dreamliner’s advocates came up with a development strategy that was supposed to be cheaper and quicker than the traditional approach: outsourcing. And Boeing didn’t outsource just the manufacturing of parts; it turned over the design, the engineering, and the manufacture of entire sections of the plane to some fifty “strategic partners.” Boeing itself ended up building less than forty per cent of the plane.

This strategy was trumpeted as a reinvention of manufacturing. But while the finance guys loved it — since it meant that Boeing had to put up less money — it was a huge headache for the engineers. . . . The more complex a supply chain, the more chances there are for something to go wrong, and Boeing had far less control than it would have if more of the operation had been in-house.

The assumption here is that vertical integration is better for quality control and for coordinating complex production systems. But that assumption is just plain wrong. As the property-rights approach to the firm has emphasized, control and coordination problems occur in internal as well as external contracting. As Thomas Hubbard points out,

The more modern thinking about procurement emphasizes that this problem appears — albeit in different forms — both when a company procures internally and when it subcontracts. The problem of getting procurement incentives right does not disappear when you produce internally rather than subcontract; it just changes. Companies struggle to get their subcontractors to produce what they want at low cost; they also struggle to get their own divisions to do so.

In other words, Boeing might have had the same problems with in-house production. “It is certainly possible that the Dreamliner’s current problems are derived from its design — it relies far more on electrical systems than Boeing’s previous planes — and that these problems would have been just as significant (and worse on the cost front) had Boeing sourced more sub-assemblies internally.” Hubbard’s essay includes a number of additional insights derived from modern theories of the firm, such as the Williamsonian idea that adaptation is the central issue distinguishing markets from hierarchies.

So, the next time you read that firms should vertically integrate to maintain quality, as yourself, are employees always easier to control than subcontractors?

The Myth of the Flattening Hierarchy

| Peter Klein |

We’ve written many posts on the popular belief that information technology, globalization, deregulation, and the like have rendered the corporate hierarchy obsolete, or at least led to a substantial “flattening” of the modern corporation (see the links here). The theory is all wrong — these environmental changes affect the costs of both internal and external governance, and the net effect on firm size and structure are ambiguous — and the data don’t support a general trend toward smaller and flatter firms.

Julie Wulf has a paper in the Fall 2012 California Management Review summarizing her careful and detailed empirical work on the shape of corporate hierarchies. (The published version is paywalled, but here is a free version.) Writes Julie:

I set out to investigate the flattening phenomenon using a variety of methods, including quantitative analysis of large datasets and more qualitative research in the field involving executive interviews and a survey on executive time use. . . .

We discovered that flattening has occurred, but it is not what it is widely assumed to be. In line with the conventional view of flattening, we find that CEOs eliminated layers in the management ranks, broadened their spans of control, and changed pay structures in ways suggesting some decisions were in fact delegated to lower levels. But, using multiple methods of analysis, we find other evidence sharply at odds with the prevailing view of flattening. In fact, flattened firms exhibited more control and decision-making at the top. Not only did CEOs centralize more functions, such that a greater number of functional managers (e.g., CFO, Chief Human Resource Officer, CIO) reported directly to them; firms also paid lower-level division managers less when functional managers joined the top team, suggesting more decisions at the top. Furthermore, CEOs report in interviews that they flattened to “get closer to the businesses” and become more involved, not less, in internal operations. Finally, our analysis of CEO time use indicates that CEOs of flattened firms allocate more time to internal interactions. Taken together, the evidence suggests that flattening transferred some decision rights from lower-level division managers to functional managers at the top. And flattening is associated with increased CEO involvement with direct reports —the second level of top management—suggesting a more hands-on CEO at the pinnacle of the hierarchy.

As they say, read the whole thing.

Arrunada Seminar: Matteo Rizzolli – Will ICT Make Registries Irrelevant?

| Matteo Rizzolli |

Will ICT Make Registries Irrelevant?

With this brief post, I would like to add some further discussion on the role of new technologies and ICTs for the evolution of registries. The book of Prof Arrunada touches upon the issue in chapter 7 where the role of technical chance is tackled. He discusses mainly the challenges in implementing different degrees of automation in pre-compiling and lodging information from interested parties and even in automating decision-making by the registry itself.

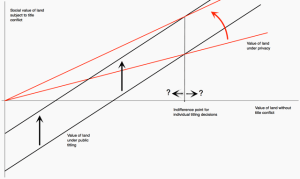

These challenges represent the costs of introducing ICTs in registries. In the book the benefits of ICTs for abating the costs of titling/recording are not discussed at length. Think of them in terms of the costs of gathering, entering, storing, organising and searching the data. I assume it is trivial to say that ICTs decrease the fixed and variable costs of registries even when some issues raised in the book are considered. In terms of the figure below (my elaboration of figure 5.1 on pg 133) this is equivalent to say that, thanks to ICTs, the black line representing the “Value of land under public titling” shifts upwards and therefore the “Indifference point for individual titling decisions” shifts leftward and makes registries more desirable.

However, i think that an important effect of ICTs is neglected in this analysis. In fact ICTs are now pervasive in most transactions. Land is observed with all sorts of satellite technology and the movement of objects and people is traced in many ways. Communications, both formal and informal are also traced and information on companies is just one click away for most individuals. I don’t want to discuss philosophical, sociological or legal aspects of this information bonanza. Neither neglect that more information doesn’t mean better or more trustworthy information. On the other I think we can agree that the quantity of information available to counterparts of a transaction is greatly increased and -more important- that verifiable evidence can be produced more easily should legal intervention in case of conflict arise.

All this information windfall may -this is my hypothesis- decrease the costs of keeping transactions out of registries and therefore improve the value of transactions under privacy. In terms of the figure below, this amounts to rotating the red line upwards and, as a result, shifting the “Indifference point for individual titling decisions” on the right.

In a sense, ICTs both i) decrease the costs of registries and ii) makes registries less relevant. On balance, it is hard for me to say which effect of ICTs may prevail. I think however this could be a very interesting empirical question to research.

Matteo Rizzolli. Assistant Professor of Law and Economics at the Free University of Bozen, Italy. Board member and secretary of the European Law & Economics Association

Click figure for higher resulution:

Recent Comments