Why Do Firms Hire Management Consultants?

| Peter Klein |

Academic economists and management scholars are often skeptical of management consulting firms. Their advice seems fluffy, ad hoc, unscientific. But consulting firms continue to prosper. Are their clients irrational?

Academic economists and management scholars are often skeptical of management consulting firms. Their advice seems fluffy, ad hoc, unscientific. But consulting firms continue to prosper. Are their clients irrational?

I always assumed signaling plays a role. One can imagine a Spence-style separating equilibrium in which high-quality firms signal their unobservable characteristics to customers, suppliers, rivals, etc. by hiring an expensive consulting firm, while low-quality firms find this prohibitively costly. Of course, all consulting firms are not alike, and there are many different types of consulting services (e.g., strategy — more fluffy; IT implementation — less fluffy).

An article in the new JMS by Donald Bergh and Patrick Gibbons looks at the signaling value of consulting, measuring the stock-market reactions to firms’ announcements of hiring a consulting firm. Excess returns are positive and significant, and increasing in the client’s prior performance — the market likes it when “good” firms hire consultants. (The effects don’t seem to depend on the reputation of the consulting firm, though.) This is consistent with my story above, though we’d need to know something about firms that could have hired a consultant but didn’t to say more.

CORS Lecture and Mises Brazil

| Peter Klein |

O&Mers in Brazil, come see me at two events this week. Thursday, 7 April, I will deliver the inaugural CORS Lecture at the University of São Paulo on “Entrepreneurship, Strategy, and Public Policy.” CORS, the Center for Organization Studies, is a new institute organized by O&M friends Sylvia Saes and Decio Zylbersztajn and involving many scholars familiar to O&M readers. The lecture is co-sponsored by the Mises Institute Brazil, my main host for the trip, and I will speak at the Institute’s Second Conference on Austrian Economics 9-10 April in Porto Alegre, along with Hans-Hermann Hoppe, Robert Murphy, Guido Hülsmann, Gabriel Zanotti, Ubiratan Iorio, Antony Mueller, Fabio Barbieri, and Dalton Gardimam. I’ll give one talk on entrepreneurship and another on networks. I would love to see you at one of these events!

Recycling an Old Post

| Peter Klein |

These important announcements appeared originally April 1, 2007.

Foss, Klein, Postrel Join Harvard Faculty

Nicolai, Steve, and I are pleased to announce that we have accepted chaired positions at Harvard University:

Cambridge, Mass., April 1, 2007 — World-renowned scholars Nicolai J. Foss, Peter G. Klein, and Steven R. Postrel will join the Harvard faculty as University Distinguished Professors and co-directors of the newly formed Long Tail Institute for the Global Economy. Says incoming President Drew Faust: “I am delighted that Professors Foss, Klein, and Postrel are joining our team. I have always admired Foss and Klein’s work on judgment-based entrepreneurship, and I enjoyed Postrel’s columns in the New York Times before he changed his name to ‘Steve.’ After reading their blog I knew they were the ones to lead Harvard into the global information age.”

Announcing Guest Bloggers Jeff Pfeffer and Bob Sutton

We’re delighted to welcome Stanford University professors Jeff Pfeffer and Bob Sutton as our newest guest bloggers. Sutton writes: “Jeff and I have recently come out of what we call our ‘Blue Period,’ characterized by moodiness and irritability toward toward economists. We now realize that economic analysis is vital to the proper understanding of organizations. What better way to flaunt our new perspective than by joining the outstanding bloggers at Organizations and Markets? We’ll also be working on our new book, Not Ready to Make Nice in the Workplace.” Welcome, Jeff and Bob!

Google Acquires O&M

This hit the news wires today:

Mountain View, April 1, 2007 — Google Corporation announced today it has acquired a majority stake in the weblog Organizations and Markets, a leading provider of news and information on organizations, strategy, entrepreneurship, and anti-postmodernism. Google CEO Larry Schmidt noted that Google is seeking to expand beyond the search-engine business. “Let’s face it, search is yesterday’s technology. There’s too much junk out there. Instead of using computers to sort our information with confusing page-ranking algorithms, the time has come to hire experts to tell us what the world is really like. The authors of Organizations and Markets are just the experts we’ve been looking for.” Google shares dropped 42% in heavy trading upon the announcement.

Here are some important April 1 stories from prior years.

Confusing Definitions of Entrepreneurship

| Peter Klein |

Some of you have heard me complain before about the confusing ways “entrepreneur” and its cognates are used in the literature. Sometimes entrepreneurship refers to an outcome or phenomenon (startups, self-employment, high-growth firms), other times to a behavior or attribute (creativity, alertness, innovation, judgment, adaptation). I find the occupational, structural, and functional taxonomy useful, but other organizing schemes may be useful too. In any case, reading the entrepreneurship literature can be a frustrating experience.

I’m glad I’m not the only one who thinks so:

[T]he book’s diversity of approaches and styles is both a strength and also an inherent weakness. Some chapters offer comprehensive descriptions over long periods of time (e.g., Hudson, Hau, Wengenroth, Chan), while others focus on narrow aspects of entrepreneurship (e.g., Yonekura and Shimizu, Mokyr, Wolcott). The first kind appears to be written for a broad audience of noneconomic historians, whereas the second type tends to be drier and more technical. Some authors follow Baumol and distinguish between productive and redistributive entrepreneurship (e.g., Hudson, Mokyr, Cain, Lamoreaux), while others use very broad definitions of entrepreneurship (e.g., Kuran, Casson and Godley, Gelderblom), and yet another group of authors associates entrepreneurship with innovation (e.g., Yonekura and Shimizu, Graham). This extreme diversity of definitions and approaches can overwhelm the reader. As a result, the volume’s ambition of tracing “the history of entrepreneurship throughout the world since antiquity” (p. vii) ends up being an interesting patchwork of insights drawn from different times and places rather than a unifying and synthetic history.

That’s from Michaël Bikard and Scott Stern’s Journal of Economic Literature review of The Invention of Enterprise: Entrepreneurship from Ancient Mesopotamia to Modern Times (ed. David S. Landes, Joel Mokyr, and William J. Baumol, Princeton, 2010), which we blogged about earlier. Obviously in a work of this scope, a common definition of entrepreneurship is likely to be elusive. But the wide variety of meanings in this lone volume give you a sense of the challenge in making sense of the wider literature.

FAIL

| Peter Klein |

Check out AdmittingFailure.com,

an open space for development professionals who recognize that the only “bad” failure is one that’s repeated. Those who are willing to share their missteps to ensure they don’t happen again. It is a community and a resource, all designed to establish new levels of transparency, collaboration, and innovation within the development sector.

Thanks to Josh Gans for the tip and some interesting discussion of failure in other contexts. (I’m not sure I’d use the term “missing market,” though; M&As, bankruptcy court, and indeed any asset markets could be described as markets for failure!)

Here’s an interesting paper by Rita McGrath on entrepreneurial failure. And of course there are huge academic literatures on divestitures, bankruptcies, and the like. At O&M we’ve often criticized bailouts and stimulus policy for retarding Schumpeterian competition by making it more difficult to identify, rectify, and learn from failures.

Information versus Knowledge

| Peter Klein |

[T]here’s enough information coming at us from all sides to leave us feeling overwhelmed, just as people in earlier ages felt smothered by what Leibniz called “that horrible mass of books that keeps on growing.” In response, 17th-century writers compiled indexes, bibliographies, compendiums and encyclopedias to winnow out the chaff. Contemplating the problem of turning information into useful knowledge, Gleick sees a similar role for blogs and aggregators, syntheses like Wikipedia, and the “vast, collaborative filter” of our connectivity. Now, as at any moment of technological disruption, he writes, “the old ways of organizing knowledge no longer work.”

But knowledge isn’t simply information that has been vetted and made comprehensible. “Medical information,” for example, evokes the flood of hits that appear when you do a Google search for “back pain” or “vitamin D.” “Medical knowledge,” on the other hand, evokes the fabric of institutions and communities that are responsible for creating, curating and diffusing what is known. In fact, you could argue that the most important role of search engines is to locate the online outcroppings of “the old ways of organizing knowledge” that we still depend on, like the N.I.H., the S.E.C., the O.E.D., the BBC, the N.Y.P.L. and ESPN.

That’s Geoffrey Nunberg reviewing James Gleick’s new book, The Information (Random House, 2011). Gleick burst onto the scene with 1987’s Chaos: The Making of New Science, which introduced the butterfly effect, Mandelbrot sets, fractal geometry, and the like into popular culture. (Don’t blame Gleick for the silly Ian Malcolm character in Jurassic Park, or the even sillier Ashton Kutcher movie.) I haven’t gotten my hands on a copy of The Information (gotta love the definite article, as in “the calculus”) but, as best as I can tell from the Google books version, Gleick doesn’t get into the Hayekian-Polanyian distinctions between parameterizable “information” and tacit knowledge that particularly interest O&M readers. (Another good quote from the review: “[T]here’s no road back from bits to meaning. For one thing, the units don’t correspond: the text of ‘War and Peace’ takes up less disk space than a Madonna music video.”) Still, the book should be worth a read.

An Early Example of a Hold-up. . .

| Scott Masten |

. . . in which two Irishman sweep fifteen or thirty Italians into an open ditch.

The context is a dispute over a contract for the supply of water to Bayonne, NJ., circa 1896, as reported in The First History of Bayonne, NJ (1904: 92):

At the mayoralty election in the spring of 1895, Egbert Seymour, on the Democratic ticket, was elected Mayor. Several of the Councilmen who were elected at this election, and two or three city officials, were opposed to the new water contract, and attempted a “hold-up.” The trouble reached its height one day during the first year of Seymour’s administration.

While employees of the water company were tapping the old mains to make the necessary water connection, some city officials arrived on the scene. Immediately there was trouble.

The New York Times article (Nov. 24, 1896) on the right (click to enlarge) elaborates, amusingly, on the manner in which the holdup was executed.

I have not yet been able to verify it but, according the previous source, “The matter was taken before the Supreme Court of the United States by the water company, and an injunction was obtained against the city. United States marshals were stationed at the scene until the work was completed, to arrest any city official who interfered.” The city eventually bought out the company in 1918.

(Wish that I had found that quotation before completing this.)

Women and Children First

| Peter Klein |

Everything you ever wanted to know about the Titanic disaster. Well, everything behavioral economists want to know, namely who survived — a case study in “Behavior under Extreme Conditions” (Journal of Economic Perspectives, Winter 2011). Bruno Frey, David Savage and Benno Torgler note that the “common assumption . . . that in such situations, self-interested reactions will predominate and social cohesion is expected to ate and social cohesion is expected to disappear. . . . However, empirical evidence on the extent to which people in the throes of a disaster react with self-regarding or with other-regarding behavior is scanty.” Fortunately (?), the sinking of the Titanic provides “a quasi-natural field experiment to explore behavior under extreme conditions of life and death.”

Everything you ever wanted to know about the Titanic disaster. Well, everything behavioral economists want to know, namely who survived — a case study in “Behavior under Extreme Conditions” (Journal of Economic Perspectives, Winter 2011). Bruno Frey, David Savage and Benno Torgler note that the “common assumption . . . that in such situations, self-interested reactions will predominate and social cohesion is expected to ate and social cohesion is expected to disappear. . . . However, empirical evidence on the extent to which people in the throes of a disaster react with self-regarding or with other-regarding behavior is scanty.” Fortunately (?), the sinking of the Titanic provides “a quasi-natural field experiment to explore behavior under extreme conditions of life and death.”

Examining data on the social and demographic characteristics of survivors and non-survivors they find that women and children were more likely to survive, other things equal, as well as the wealthy and those in a stronger social network (traveling with family members, or being part of the crew). A morbidly interesting paper, to be sure.

McQuinn Center for Entrepreneurial Leadership

| Peter Klein |

Earlier this academic year I assumed the Directorship of the McQuinn Center for Entrepreneurial Leadership here at the University of Missouri. My colleague (and former O&M guest blogger) Randy Westgren retains the position of McQuinn Chair. The McQuinn Chair was established in 2004 through a generous gift from Al and Mary Agnes McQuinn, and the Center was created soon afterwards by Bruce Bullock, the inaugural McQuinn Chair.

Look for a slate of exciting programs and activities about entrepreneurship, organization, innovation, strategy, and more in the coming months. To keep you up to date on the Center’s activities, as well as news and information from the wider world of entrepreneurship, we’re blogging as well at entrepreneurship@McQuinn.

Coasian or Coasean?

| Peter Klein |

For years I described things relating to Ronald Coase as “Coasian.” Walter Block continually needled me about this, insisting the proper spelling was “Coasean,” but I resisted. Now I see more people using the latter spelling, and I’ve started using it myself. But which is correct? I beats e, but not by much, in a Googlefight. But I think a more targeted crowdsourcing arrangement is warranted. So, dear O&M readers, which do you prefer? Vote below.

Addendum: Thanks to Scott for pointing out that this was debated before at Volokh, where many of the critical issues — and the most obvious snarks — were already presented. To me, the fact that Coase himself, and people at Chicago Law, use “Coasian” seems a pretty strong argument in favor of the non-standard spelling. But one can make a good case for either.

If You’re Not a Cynic Yet, this Might Help…

| Lasse Lien |

Revolving Door Lobbyists

Jordi Blanes i Vidal, Mirko Draca, Christian Fons-Rosen.Abstract: Washington’s “revolving door” — the movement from government service into the lobbying industry — is regarded as a major concern for policy-making. We study how ex-government staffers benefit from the personal connections acquired during their public service. Lobbyists with experience in the office of a US Senator suffer a 24% drop in generated revenue when that Senator leaves office. The effect is immediate, discontinuous around the exit period and long-lasting. Consistent with the notion that lobbyists sell access to powerful politicians, the drop in revenue is increasing in the seniority of and committee assignments power held by the exiting politician.

By See the full paper here.

Paper Titles I Wish I’d Written

| Peter Klein |

“Schumacher meets Schumpeter” by Raphael Kaplinsky (Research Policy, March 2011). Asks if tech innovation benefits mostly the wealthy or the poorest in society as well. Great alliteration. (Thanks to Christos Kolympiris for the tip.)

I could still write books on Herbert Simon’s contributions (Simon Says), new developments in the resource-based view (Barney and Friends), or Marxist eschatology (Serf’s Up).

Management Textbooks Bungle Weber

| Peter Klein |

Most management scholars, like most economists, have little interest in doctrinal history, so it’s not surprising they don’t pay much attention to the history of management thought. But Stephen Cummings and Todd Bridgman’s “The Relevant Past: Why the History of Management Should Be Critical for Our Future” (Academy of Management Learning and Education, March 2011) is an eye-opener. Focusing on Max Weber, Cummings and Bridgman document a series of whoppers that appear consistently in leading management texts, such as the belief that “ideal type” means best or optimal; that Weber did his major work in the 1940s (Parsons’s translation of Wirtschaft and Gesellschaft appeared in 1947, 27 years after Weber’s death); that Weber personally admired bureaucracy (In Search of Excellence avers that Weber “pooh-poohed charismatic leadership and doted on bureaucracy”); and other gross misunderstandings. FAIL.

Stockman on the Crisis that Wasn’t

| Peter Klein |

I’ve been complaining since 2008 that the justification for TARP and other forms of monetary and fiscal stimulus was never clearly stated. “The financial system would have collapsed” if Paulson and Bernanke had not made their unprecedented moves. But there was never any serious analysis or argument for this, just a series of bold (bald?) assertions.

I’ve been complaining since 2008 that the justification for TARP and other forms of monetary and fiscal stimulus was never clearly stated. “The financial system would have collapsed” if Paulson and Bernanke had not made their unprecedented moves. But there was never any serious analysis or argument for this, just a series of bold (bald?) assertions.

This weekend’s ASC speech by former Reagan OMB Director David Stockman took the same line:

Based on the panicked advice of Paulson and Bernanke, of course, the president had the misapprehension that without a bailout “this sucker is going down.” Yet 30 months after the fact, evidence that the American economy had been on the edge of a nuclear-style meltdown is nowhere to be found. . . .

Still, the urban legend persists that in September 2008 the payments system was on the cusp of crashing, and that absent the bailouts, companies would have missed payrolls, ATMs would have gone dark and general financial disintegration would have ensued.

But the only thing that even faintly hints of this fiction is the commercial-paper market dislocation. Upon examination, however, it is evident that what actually evaporated in this sector was not the cash needed for payrolls, but billions in phony book profits, which banks had previously obtained through yield-curve arbitrages that were now violently unwinding.

Stockman argues (persuasively, in my view) that the commercial-paper market was going through a much-needed correction, and that the best response would have been to let the loan market adjust, according to market forces. After all, “nowhere was it written that GE Capital or the Bank One credit-card conduit, to pick two heavy users of the space, had a Federal entitlement to cheap commercial paper — so that they could earn fat spreads on their loan books.”

Miscellaneous Links

| Peter Klein |

- Max Weber versus Rodney Stark. Read the very interesting comment thread at this ThinkMarkets post.

- US firms can expect lower worker productivity starting this week. Duh.

- The Austrian School of Economics: A History of Its Ideas, Ambassadors, and Institutions by Eugen Maria Schulak and Herbert Unterköfler. Newly translated from the 2009 German-language original. (Translator Arlene Oost-Zinner was a production editor on my 2010 book and did a wonderful job — no cracks, please, about the need to have my stilted prose translated into passable English.)

- Do you know what really important US patent was granted on March 14?

Interesting New NBER Papers

| Peter Klein |

Matching Firms, Managers, and Incentives

Oriana Bandiera, Andrea Prat, Luigi Guiso, Raffaella Sadun

January 2011

We exploit a unique combination of administrative sources and survey data to study the match between firms and managers. The data includes manager characteristics, such as risk aversion and talent; firm characteristics, such as ownership; detailed measures of managerial practices relative to incentives, dismissals and promotions; and measurable outcomes, for the firm and for the manager. A parsimonious model of matching and incentive provision generates an array of implications that can be tested with our data. Our contribution is twofold. We disentangle the role of risk-aversion and talent in determining how firms select and motivate managers. In particular, risk-averse managers are matched with firms that offer low-powered contracts. We also show that empirical findings linking governance, incentives, and performance that are typically observed in isolation, can instead be interpreted within a simple unified matching framework.

Business Failures by Industry in the United States, 1895 to 1939: A Statistical History

Gary Richardson, Michael Gou

March 2011

Dun’s Review began publishing monthly data on bankruptcies by branch of business during the 1890s. This essay reconstructs that series, links it to its successors, and discusses how it can be used for economic analysis.

The Consequences of Financial Innovation: A Counterfactual Research Agenda

Josh Lerner, Peter Tufano

February 2011

Financial innovation has been both praised as the engine of growth of society and castigated for being the source of the weakness of the economy. In this paper, we review the literature on financial innovation and highlight the similarities and differences between financial innovation and other forms of innovation. We also propose a research agenda to systematically address the social welfare implications of financial innovation. To complement existing empirical and theoretical methods, we propose that scholars examine case studies of systemic (widely adopted) innovations, explicitly considering counterfactual histories had the innovations never been invented or adopted.

Something to Ruin Your Weekend

| Lasse Lien |

On a Monday morning, a professor says to his class, “I will give you a surprise examination someday this week. It may be today, tomorrow, Wednesday, Thursday, or Friday at the latest. On the morning of the examination, when you come to class, you will not know that this is the day of the examination.”

Well, a logic student reasoned as follows: “Obviously I can’t get the exam on the last day, Friday, because if I haven’t gotten the exam by the end of Thursday’s class, then on Friday morning I’ll know that this is the day, and the exam won’t be a surprise. This rules out Friday, so I now know that Thursday is the last possible day. And, if I don’t get the exam by the end of Wednesday, then I’ll know on Thursday morning that this must be the day (because I have already ruled out Friday), hence it won’t be a surprise. So Thursday is also ruled out.”

The student then ruled out Wednesday by the same argument, then Tuesday, and finally Monday, the day on which the professor was speaking. He concluded: “Therefore I cannot get the exam at all; the professor cannot possibly fulfill his statement.” Just then, the professor said: “Now I will give you your exam.” The student was most surprised, but the professor seems to have kept his word.

Creative Destruction in Popular Culture

| Peter Klein |

Thanks to Thomas B. for forwarding links to US Sen. Rand Paul’s Monday-night appearance on the Daily Show (part 1, part 2, part 3). At the start of part 3, while discussing government bailouts, Paul uses the words “creative destruction,” and Jon Stewart bursts out laughing, apparently hearing the term for the first time. I guess Schumpeter is not as culturally relevant as I thought!

The show had some interesting moments, but I found the discussions (in the parts I watched) pretty shallow. Stewart was grilling Paul on his “free-market” views, focusing on health, safety, and environmental regulation. Both Paul and Stewart took the milquetoast position that sure, some of this type of regulation is needed, but it shouldn’t be “too much.” They didn’t get into a serious discussion of theory or evidence, however, or explore specific trade-offs. There are huge political economy and public-choice literatures on the FDA, EPA, OSHA, etc., showing that these organizations are easily captured, tend to retard innovation, fail to weigh marginal benefits and costs, and so on. The Journal of Law and Economics under Coase’s leadership made its bones on these kinds of studies in the 1970s. The FDA has been a particular target. The Stewart view also ignores comparative institutional analysis — e.g., the role of private ordering (third-party certification, reputation, etc. ) in the protection of health and safety.

At least Paul didn’t say he intended to become the best Senator, horseman, and lover in all Washington!

Kuhn’s Ashtray

| Peter Klein |

You know about Wittgenstein’s Poker. But have you heard of Kuhn’s ashtray?

We began arguing. Kuhn had attacked my Whiggish use of the term “displacement current.” I had failed, in his view, to put myself in the mindset of Maxwell’s first attempts at creating a theory of electricity and magnetism. I felt that Kuhn had misinterpreted my paper, and that he — not me — had provided a Whiggish interpretation of Maxwell. I said, “You refuse to look through my telescope.” And he said, “It’s not a telescope, Errol. It’s a kaleidoscope.” (In this respect, he was probably right.)

The conversation took a turn for the ugly. Were my problems with him, or were they with his philosophy?

I asked him, “If paradigms are really incommensurable, how is history of science possible? Wouldn’t we be merely interpreting the past in the light of the present? Wouldn’t the past be inaccessible to us? Wouldn’t it be ‘incommensurable?’ ”

He started moaning. He put his head in his hands and was muttering, “He’s trying to kill me. He’s trying to kill me.”

And then I added, “…except for someone who imagines himself to be God.”

It was at this point that Kuhn threw the ashtray at me.

The account comes from filmmaker Errol Morris, then Thomas Kuhn’s graduate student at Princeton, who adds that “I had imagined graduate school as a shining city on a hill, but it turned out to be more like an extended visit with a bear in a cave.” (HT: Pete Boettke). I have not used Kuhn’s particular technique with my own students, though I admit it has a certain visceral appeal. Nor have I been on the receiving end of such behavior, though a conference participant once opened his presentation by saying, “My paper is basically devoted to refuting everything in Klein’s paper.” (Fortunately, I was the moderator, and responded immediately, “Thank you, your time is up.”)

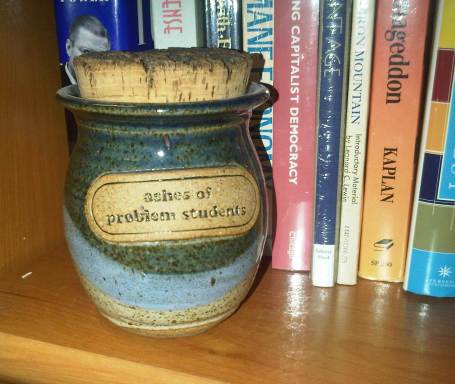

Back to students: I do keep this decorative item by the entrance to my office, placed for all to see:

Chairman Mao and Comparative Institutional Analysis

| Peter Klein |

Coase? Williamson? No, Mao Tse-Tung:

Concrete analysis of concrete conditions, Lenin said, is “the most essential thing in Marxism, the living soul of Marxism.” Lacking an analytical approach, many of our comrades do not want to go deeply into complex matters, to analyse and study them over and over again, but like to draw simple conclusions which are either absolutely affirmative or absolutely negative. The fact that our newspapers are lacking in analytical articles and that the habit of analysis is not yet fully cultivated in the Party shows that there are such shortcomings. From now on we should remedy this state of affairs.

(Thanks to Pablo for the tip.)

"I say to you, Comrades. . . . No more blackboard economics!"

Recent Comments