Posts filed under ‘Institutions’

Private, For-Profit Legal Education

| Peter Klein |

The WSJ profiles InfiLaw, a network of private-equity backed, for-profit law schools that is challenging the established model of legal education. From what I understand, InfiLaw seems to be the University of Phoenix of law schools, providing vocationally oriented training for the lower-end of the market (but, unlike for-profit business schools, charging upmarket prices).

InfiLaw’s schools aren’t designed to compete with the Harvards and Stanfords. The approach, the company says, has mostly been to target students, including many minorities, whose grade-point averages or LSAT scores don’t qualify them for admission at the top schools. . . .

Some in the academy think InfiLaw is compounding the problems in legal education, which is graduating far more students than there are entry-level jobs for lawyers. Critics, including former students who have sued Florida Coastal, see the company as a predatory outfit that peddles false promises to students in exchange for high tuitions.

Others think criticisms of InfiLaw are based on elitism embedded within the legal academy,

As we’ve noted before, it is unlikely that newer, private, for-profit colleges, universities, and professional schools can compete head-to-head with the traditional schools, but why should they? Certainly there is room for more creativity, experimentation, and innovation, structurally and pedagogically, in legal education, as with other forms of higher learning. InfiLaw may be ineffective, or even a scam, but viva la diversité!

World Interdisciplinary Network for Institutional Research

| Dick Langlois |

I have recently become involved with a new organization that many readers may be interested in. It’s called the World Interdisciplinary Network for Institutional Research (WINIR). From the website:

I have recently become involved with a new organization that many readers may be interested in. It’s called the World Interdisciplinary Network for Institutional Research (WINIR). From the website:

WINIR is a specialist but global network. It is set up to complement rather than rival other organisations that have the study of institutions on their agenda. Unconfined to any single academic discipline, it accepts contributions from any approach that can help us understand the nature and role of institutions. While other organisations are intended to act as broad forums for all kinds of research in the social sciences, WINIR aims to build an adaptable and interdisciplinary theoretical consensus concerning core issues, which can be a basis for cumulative learning and scientific progress in the exciting and rapidly-expanding area of institutional research.

You can learn more and sign up here. If you join now, you will be considered a founding member. WINIR is tentatively planning a conference for next year near London and one the year after that in Rio.

From MOOC to MOOR

| Peter Klein |

Via John Hagel, a story on MOOR — Massively Open Online Research. A UC San Diego computer science and engineering professor is teaching a MOOC (massively open online course) that includes a research component. “All students who sign up for the course will be given an opportunity to work on specific research projects under the leadership of prominent bioinformatics scientists from different countries, who have agreed to interact and mentor their respective teams.” The idea of crowdsourcing research isn’t completely new, but this particular blend of MOO-ish teaching and research constitutes an interesting experiment (see also this). The MOO model is gaining some traction in the scientific publishing world as well.

New Member of the Academy of … Family

| Nicolai Foss |

So, we have the Academy of Management Review and the Academy of Management Journal, commonly acknowledged as the top theory and empirical management journal, respectively. We are also blessed with the Academy of Management Perspective (formerly, the Academy of Management Executive), which seeks (successfully) to style itself as the management research equivalent to the Journal of Economic Perspectives. Then there is also the Academy of Management Learning and Education and there is the rather recently established Academy of Management Annals.

The sixth member of the family is now being launched, and has assumed the name of the Academy of Management Discoveries. The founding editor is Andrew H. Van de Ven who is the Vernon H. Heath Professor of Organizational Innovation and Change in the Carlson School of Management of the University of Minnesota, a major figure in organization theory over the last 4 decades, and a former President of the Academy of Management. According to the journal’s website, AMD will”promote the creation and dissemination of new empirical evidence that strengthens our understanding of substantively important yet poorly understood phenomena concerning management and organizations.” The journal is “phenomenon-driven” rather than aimed at theory testing per se.

In the end, I am not entirely convinced that this is that different from the mission and practice of the Academy of Management Journal, and I can see a scenario where we get an AMJ #2. However, the journal is open to replication research and “evidence-based assessments”, and certainly the first characteristic would seem to set it apart from the AMJ (even if replication research and evidence-based assessments would seem to pull away from phenomenon-driven discovery and towards theory testing).

Here is a brief YouTube clip with Van de Ven talking about the kind of research that the AMD will publish.

Manuscripts can be submitted here.

Varia on Impact Factors, Journals, Publishing …

| Nicolai Foss |

- Here is an interesting popular piece from The Atlantic about, among other things, a Brazilian citation cartel.

- Yes, replication papers are publishable in social science journals; check out this post.

- We have Management Science, Marketing Science, Organization Science … Now we will also have Sociological Science.

- Very interesting piece on harmful, unintended consequences of journal rankings, such as more misconduct, more retractions, less reliable research, and so on.

Ronald Coase (1910-2013)

| Peter Klein |

Ronald Coase passed away today at the age of 102. One of the most influential economists of the 20th century, perhaps of all time. His “Problem of Social Cost” (1960) has 21,692 Google Scholar cites, and “The Nature of the Firm” has 24,501. Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nations, summed across editions, has about 30,000. Coase changed the way economists think about the business firm and the way they think about property rights and liability. He largely introduced the concepts of transaction costs, comparative institutional analysis, and government failure. Not all economist have agreed with his arguments and conceptual frameworks, but they radically changed the terms of debate in the economics of law, welfare, industry, and more. He is the key figure in the “new institutional economics” (and co-founder, and first president, of the International Society for New Institutional Economics).

Coase did all these things despite — or because of? — not holding a PhD in economics, not doing any math or statistics, and not, for much of his career, working in an economics department.

We’ve written so much on Coase already, on these pages and in our published work, that it’s hard to know what else to say in a blog post. Perhaps we should just invite you to browse old O&M posts mentioning Coase (including this one, posted last week).

The blogosphere will be filled in the coming days with analyses, reminiscences, and tributes. You can find your favorites easily enough (try searching Twitter, for example). I’ll just share two of my favorite memories. The first comes from the inaugural meeting of the International Society for New Institutional Economics in 1997. After a discussion about the best empirical strategy for that emerging discipline. Harold Demsetz stood up and said “Please, no more papers about Fisher Body and GM!” Coase, who was then at the podium, surprised the crowd by replying, “I’m sorry, Harold, that is exactly the subject of my next paper!” (That turned out to be his 2005 JEMS paper, described here.) A few years later, I helped entertain Coase during his visit to the University of Missouri for the CORI Distinguished Lecture. At lunch we talked about his disagreement with Ben Klein on asset specificity. After the lunch he got up, shook my hand, and announced, with evident satisfaction: “I see all Kleins are not alike.”

ContractsProf Blog Symposium on Stuart Macaulay

| Peter Klein |

Economists and management scholars know Stuart Macaulay’s landmark 1963 article, “Non-Contractual Relations in Business: A Preliminary Study,” as the foundation for modern work in relational contracting. As Williamson (1985, p. 10) put it, “Macaulay’s studies of contractual practices support the view that contractual disputes and ambiguities are more often settled by private ordering than by appeal to the courts — which is in sharp contrast with the neoclassical presumptions of both law and economics.” A new book on Macaulay has promoted a symposium over at the ContractsProf Blog. I’m particularly looking forward to this week’s contributions, especially the one from Gillian Hadfield.

Bowling for Fascism

| Dick Langlois |

Speaking of Robert Putnam: Although I think the idea of social capital has its uses, Putnam’s claim that civic engagement in the US has been declining was long ago demolished by my late UConn colleague Everett Ladd. But I have also thought that social capital – and the Romantic “communitarian” movement in general – has been blind to the authoritarian side of community. The always-interesting Hans-Joachim Voth and his co-authors have illustrated this in a dramatic way in a new working paper. Here is the abtract.

Social capital – a dense network of associations facilitating cooperation within a community – typically leads to positive political and economic outcomes, as demonstrated by a large literature following Putnam. A growing literature emphasizes the potentially “dark side” of social capital. This paper examines the role of social capital in the downfall of democracy in interwar Germany by analyzing Nazi party entry rates in a cross-section of towns and cities. Before the Nazi Party’s triumphs at the ballot box, it built an extensive organizational structure, becoming a mass movement with nearly a million members by early 1933. We show that dense networks of civic associations such as bowling clubs, animal breeder associations, or choirs facilitated the rise of the Nazi Party. The effects are large: Towns with one standard deviation higher association density saw at least one-third faster growth in the strength of the Nazi Party. IV results based on 19th century measures of social capital reinforce our conclusions. In addition, all types of associations – veteran associations and non-military clubs, “bridging” and “bonding” associations – positively predict NS party entry. These results suggest that social capital in Weimar Germany aided the rise of the Nazi movement that ultimately destroyed Germany’s first democracy.

Sampling on the Dependent Variable, Robert Putnam Edition

| Peter Klein |

Famed sociologist Robert Putnam makes his case for government funding of social science research:

One of the harshest critics of National Science Foundation funding of political science has even praised my study [on civil society and democracy] as “one of the most influential pieces of practical research in the last half-century.”

Ironically, however, if the recent amendment by Sen. Tom Coburn (R-Okla.) that restricts NSF funding for political science had been in effect when I began this research, it never would have gotten off the ground since the foundational grant that made this project possible came from the NSF Political Science Program.

Well, yes, if it hadn’t been for NASA, we wouldn’t have put a man on the moon. What this shows about the average or marginal productivity of government science funding is a little unclear to me.

Of course, Putnam’s piece is a short editorial making an emotional, rather than logical, appeal. But this kind of appeal seems to be all the political scientists have offered in response to the hated Coburn Amendment.

Culture, Entrepreneurship, and Innovation: French Edition

| Peter Klein |

Quote of the day, from Peter Gumbel’s France’s Got Talent: The Woeful Consequences of French Elitism, an interesting first-person account of the French educational system:

[T]he patterns of behavior established at [French] school appear to continue in later life, reproducing themselves most obviously in the workplace. If you learn from an early age that volunteering answers at school may prompt humiliating put-downs from your teachers, how active a participant will you be in office strategy discussions in the presence of an authoritarian boss? If working together in groups was discouraged as a child, how good a team player will you be as a grown-up? If you are made to believe as a 10-year-old that it’s worse to give a wrong answer than to give no answer at all, how will that influence your inclination to take risks?

I won’t repeat the apocryphal George W. Bush quote that “the problem with France’s economy is that the French have no word for entrepreneur,” but I will say that I have found French university students to be less aggressive than their US or Scandinavian equivalents. To be fair, when I’ve taught in France it has been in English, and I initially attributed the students’ reluctance to speak up, to answer questions, and to challenge the instructor to worries about English proficiency. But talking to French colleagues, and reading accounts like Gumbel’s (based on his experiences teaching at Sciences Po), I think the problem is largely cultural. The French system tends to favor conformity and memorization over creativity and spontaneity, which may or may not have a harmful effect on the performance of French organizations and French attitudes toward entrepreneurship and innovation.

I’m curious to know what our French readers think (but don’t hammer me with Bourdieu or Crozier references, please).

Mokyr on Cultural Entrepreneurship

| Peter Klein |

I am wary of adding yet another conceptual margin for entrepreneurial action but I highly recommend a new (and for the moment, ungated) paper in the Scandinavian Economic History Review by the distinguished economic historian Joel Mokyr on “cultural entrepreneurship.” Starting from a broadly Schumpeterian perspective, Mokyr focuses on individuals who introduce and disseminate novel ideas:

[E]ach individual makes cultural choices taking as given what others believe. It is not a priori obvious how that affects one’s choices. It may affect them positively because conformism implies that there is some social cost associated with deviancy, or because people may reason that if the majority believes a certain thing, there may be wisdom in it (thus saving on information costs). But there can be a reverse reaction as well, with non-conformists perversely rebelling against existing beliefs. What matters for my purposes is that for a small number of individuals, the beliefs of others are not given but can be changed. I shall refer to those people as cultural entrepreneurs. Their function is much like entrepreneurs in the realm of production: individuals who refuse to take the existing technology or market structure as given and try to change it and, of course, benefit personally in the process. Much like other entrepreneurs, the vast bulk of them make fairly marginal changes in our cultural menus, but a few stand out as having affected them in substantial and palpable ways.

Succinctly expressed: “cultural entrepreneurs are the creators of epistemic focal points that people can coordinate their beliefs on.”

Mokyr’s focus, like Schumpeter’s, is not entrepreneurship per se, but its effects, particularly on long-run economic growth, and his entrepreneurship construct is somewhat undertheorized. But he provides fascinating examples, ranging from Mohammed and Luther to Francis Bacon, Isaac Newton, and Adam Smith. He focuses in particular on Bacon and Newton, describing Bacon’s work as “the coordination device which served as the point of departure for thinkers and experimentalists for two centuries to come. The economic effects of these changes remained latent and subterranean for many decades, but eventually they erupted in the Industrial Revolution and the subsequent processes of technological change.” Newton and the Royal Society “raise[d] the social standing of scientists and researchers as people who should be respected and supported and [provided] them with a comfortable material existence.” (Mostly good.)

I’m not an expert on cultural theory or history and am not sure how much the “cultural entrepreneur” construct ads to our understanding of cultural change (other than relabeling, a frequent worry in entrepreneurship studies). But the paper is a great read, highly provocative and informative, and addresses big questions. Check it out.

Rise of the Three-Essays Dissertation

| Peter Klein |

Almost all dissertations in economics and business are of the “three-essays” variety, rather than conventional book-length treatises. The main reason is pragmatic: economics, management, finance, accounting, etc. are mainly discussed in journal articles, not books. Students writing treatises must spend the first year post PhD converting the dissertation into articles for publication; why not write them that way from the start? (An extreme example — perhaps apocryphal — concerns Larry Summers, who began teaching at MIT several years before receiving his PhD from Harvard. Rumor has it he forgot to submit the PhD thesis, and simply bundled three of his published articles and turned it in.)

Some counter that the traditional model, or some variant of it, has value — for instance, the treatise conventionally includes a lengthy literature review, more than would be acceptable for a published journal article, which demonstrates the student’s mastery of the relevant literature. My view is that the standalone literature review is redundant at best; the student’s mastery of the material should be manifest in the research findings, without extra recitation of who said what. I tell students: don’t waste time putting anything in the dissertation that is not intended for publication!

The May 2013 AER has a piece by Wendy Stock and John Siegfried, “One Essay on Dissertation Formats in Economics,” on the essays-versus-treatise question. The evidence seems to weigh pretty heavily against the treatise:

Dissertations in economics have changed dramatically over the past forty years, from primarily treatise-length books to sets of essays on related topics. We document trends in essay-style dissertations across several metrics, using data on dissertation format, PhD program characteristics, demographics, job market outcomes, and early career research productivity for two large samples of US PhDs graduating in 1996-1997 or 2001-2002. Students at higher ranked PhD programs, citizens outside the United States, and microeconomics students have been at the forefront of this trend. Economics PhD graduates who take jobs as academics are more likely to have written essay-style dissertations, while those who take government jobs are more likely to have written a treatise. Finally, most of the evidence suggests that essay-style dissertations enhance economists’ early career research productivity.

The paywalled article is here; a pre-publication version is here. (Thanks to Laura McCann for the pointer.)

More Bad News for Microfinance

| Peter Klein |

Microfinance and microenterprise have been touted as a new model for economic development, a way to encourage investment, innovation, and business creation and raise living standards without having to go through large-scale industrialization. We’ve tended to be skeptical, however, particularly about the most touted microfinance providers such as the Grameen Bank. Theoretically, the kinds of repayment plays that make microfinance feasible (high interest rates, strong peer monitoring) seem to limit its scope; besides, not everyone wants to be a business owner. The empirical evidence has not been encouraging — microfinance may achieve some social goals, like a sense of empowerment among microenterprise owners, but does not seem to have much impact on overall economic activity. It may not be possible to jump from a largely rural, agrarian society to an entrepreneurial capitalist one without going through a period of large-scale industrial development.

These musings are inspired by a new NBER working paper from the J-PAL group which uses a randomized controlled trial to study the effects of microfinance in an urban Indian setting. The results confirm the suspicions above: access to microfinance brings about some changes in behavior, but has no noticeable effect on standards of living or overall economic performance. Here’s the info:

The Miracle of Microfinance? Evidence from a Randomized Evaluation

Esther Duflo, Abhijit Banerjee, Rachel Glennerster, Cynthia G. Kinnan

NBER Working Paper No. 18950, May 2013This paper reports on the first randomized evaluation of the impact of introducing the standard microcredit group-based lending product in a new market. In 2005, half of 104 slums in Hyderabad, India were randomly selected for opening of a branch of a particular microfinance institution (Spandana) while the remainder were not, although other MFIs were free to enter those slums. Fifteen to 18 months after Spandana began lending in treated areas, households were 8.8 percentage points more likely to have a microcredit loan. They were no more likely to start any new business, although they were more likely to start several at once, and they invested more in their existing businesses. There was no effect on average monthly expenditure per capita. Expenditure on durable goods increased in treated areas, while expenditures on “temptation goods” declined. Three to four years after the initial expansion (after many of the control slums had started getting credit from Spandana and other MFIs ), the probability of borrowing from an MFI in treatment and comparison slums was the same, but on average households in treatment slums had been borrowing for longer and in larger amounts. Consumption was still no different in treatment areas, and the average business was still no more profitable, although we find an increase in profits at the top end. We found no changes in any of the development outcomes that are often believed to be affected by microfinance, including health, education, and women’s empowerment. The results of this study are largely consistent with those of four other evaluations of similar programs in different contexts.

Institutions and Economic Change

| Dick Langlois |

In September I will be part of a symposium on “Institutions and Economic Change,” organized by Geoff Hodgson’s Group for Research in Organisational Evolution. The workshop will be held on 20-21 September 2013 at Hitchin Priory, Hitchin, Hertfordshire, England. Here is the program and call for participation:

Speakers:

Masahiko Aoki (Stanford University, USA)

“Between the Economy and the Polity: Causation or Correlation. Theory and a Historical Case from China”Francesca Gagliardi (University of Hertfordshire, UK)

“A Bibliometric Analysis of the Literature on Institutional Complementarities”Geoffrey Hodgson (University of Hertfordshire, UK)

“A Manifesto for Legal Institutionalism”Jack Knight (Duke University, USA)

“Courts and Institutional Change”Suzanne Konzelmann (Birkbeck College, University of London, UK)

“‘Picking winners’ in a Liberal Market Economy: Modern Day Heresy – or Essential Strategy for Competitive Success?”Richard Langlois (University of Connecticut, USA)

“The Institutional Revolution: A Review Essay”Ugo Pagano (University of Siena, Italy)

“Synergy, Conflict and Institutional Complementarities”Abstracts are available on this GROE webpage: uhbs-groe.org/workshops.htm

This workshop is designed to provide in-depth discussion of cutting-edge issues, in a forum that permits the attention to detail and definition that is often lacking in larger, conference-style events. The expected maximum number of participants is 50. Our past Workshops have filled up rapidly, so please book early to avoid disappointment. The workshop will include a poster session where participants may present their research, as long as it is related to the workshop theme. To apply to be included in the poster session send an abstract of your paper to Francesca Gagliardi (f.gagliardi@herts.ac.uk). To reserve a place on the workshop please visit store.herts.ac.uk/groeworkshop

The Future of Publishing

| Peter Klein |

The current issue of Nature features a special section on “The Future of Publishing” (thanks to Jason for the tip). The lead editorial discusses the results of a survey of scientists which shows, perhaps surprisingly, that support for online, open-access publishing is lukewarm. It’s not just the commercial publishers who want to maintain the paywalls. The entire issue is filled with interesting stuff, so check it out.

The current issue of Nature features a special section on “The Future of Publishing” (thanks to Jason for the tip). The lead editorial discusses the results of a survey of scientists which shows, perhaps surprisingly, that support for online, open-access publishing is lukewarm. It’s not just the commercial publishers who want to maintain the paywalls. The entire issue is filled with interesting stuff, so check it out.

Blanchard on Fed Independence

| Peter Klein |

I’ve argued before (1, 2) that the usual arguments for central bank independence aren’t very strong, particularly in the current environment where Bernanke has interpreted the “unusual and exigent circumstances” provision to mean “I will do whatever I want.” (This was a major point in my Congressional testimony about the Fed.) So it was nice to see Olivier Blanchard express similar reservations in an interview published in today’s WSJ (I assume it’s not an April Fool’s Day prank):

One of the major achievements of the last 20 years is that most central banks have become independent of elected governments. Independence was given because the mandate and the tools were very clear. The mandate was primarily inflation, which can be observed over time. The tool was some short-term interest rate that could be used by the central bank to try to achieve the inflation target. In this case, you can give some independence to the institution in charge of this because the objective is perfectly well defined, and everybody can basically observe how well the central bank does..

If you think now of central banks as having a much larger set of responsibilities and a much larger set of tools, then the issue of central bank independence becomes much more difficult. Do you actually want to give the central bank the independence to choose loan-to-value ratios without any supervision from the political process. Isn’t this going to lead to a democratic deficit in a way in which the central bank becomes too powerful? I’m sure there are ways out. Perhaps there could be independence with respect to some dimensions of monetary policy - the traditional ones — and some supervision for the rest or some interaction with a political process.

Henderson on Business Ethics

| Dick Langlois |

Rebecca Henderson, one of my favorite management scholars, has a new paper (with Karthik Ramanna) on – Milton Friedman and business ethics. Here’s the abstract.

Managers and Market Capitalism

In a capitalist system based on free markets, do managers have responsibilities to the system itself, and, in particular, should these responsibilities shape their behavior when they are attempting to structure those institutions of capitalism that are determined through a political process? A prevailing view — perhaps most eloquently argued by Milton Friedman — is that managers should act to maximize shareholder value, and thus that they should take every opportunity (within the bounds of the law) to structure market institutions so as to increase profitability. We maintain here that if the political process is sufficiently ‘thick,’ in that diverse views are well-represented and if politicians and regulators cannot be easily captured, then this shareholder-return view of political engagement is unlikely to reduce social welfare in the aggregate and thus damage the legitimacy of market capitalism. However, we contend that sometimes the political process of determining institutions of capitalism is ‘thin,’ in that managers find themselves with specialized technical knowledge unavailable to outsiders and with little political opposition — such as in the case of determining certain corporate accounting standards that define corporate profitability. In these circumstances, we argue that managers have a responsibility to structure market institutions so as to preserve the legitimacy of market capitalism, even if doing so is at the expense of corporate profits. We make this argument on grounds that it is both in managers’ self-interest and, expanding on Friedman, managers’ ethical duty. We provide a framework for future research to explore and develop these arguments.

On the one hand, we might quibble about whether they get Friedman right. Friedman meant in the first instance that managers should pursue their self-interest within the framework of “good” institutions, not in the (Public Choice) context of changing the institutional framework itself. I haven’t actually gone back to see what Friedman says about this, but here is how Henderson and Ramanna interpret the Chicago tradition: “Friedman and his colleagues were keenly aware that capitalism can only fulfill its normative promise when markets are free and unconstrained, and that managers (and others) have strong incentives to violate the conditions that support such markets (e.g., Stigler, 1971). But they argued both that dynamic markets tend to be self-healing in that the dynamics of competition itself generates the institutions and actions that maintain competition and that government could be relied on to maintain those institutions—such as the legal system—that are more effectively provided by the state (on this latter point, see, in particular, Hayek, 1951).” There is a sense in which Chicago saw (and economic liberals in general see) the system as self-healing in the longest of runs: every inefficiency is ultimately a profit opportunity for someone who can transmute deadweight loss into producer’s surplus; and economic growth cures a lot of ills. But one can hardly accuse Chicago of being insensitive to those bad incentives for rent-seeking in the short and medium term.

On the other hand, Henderson and Ramanna make a valuable point when they draw our attention to the gray area in which market-supporting institutions (the same term I tend to use) are often forged through private action or through public action in which the private actors possess the necessary local knowledge. There is a scattered literature on this – the setting of technical standards, for example – but it is not a major focus of Public Choice or political economy. Perhaps it is naïve to say that managers in this gray area have an ethical duty to support institutions that make the pie bigger rather than institutions that transfer income to them. But what else can we say? It’s a lot better than blathering on about “public-private partnerships,” which are frequently cover for rent-seeking behavior. One (possibly embarrassing) implication of this stance is that it makes a hero of the much-reviled Charles Koch, who funds opposition to many of the rent-seeking institutions from which his own company benefits.

At one point Henderson and Ramanna mention the Great Depression as a “market failure” that incubated anti-capitalist sentiment. The second part of that assertion is certainly true, but the Depression was not a market failure but a spectacular failure of government. (Read Friedman (!), whose once-controversial view about this is now widely accepted by economic historians and monetary economists, including Ben Bernanke.) The Depression is actually an interesting case study in the gray area of institutions. Before the Fed, private financiers acted collectively to provide the public good of stopping bank panics. Now that role has fallen to the state, with private interests – and their asymmetrical local knowledge – influencing the bailout process. Which system was less corrupt? A more general question: are there any examples of fully private creation of institutions in which the self-interest of the participants led to inefficient rent-seeking?

Trento Summer School on Modularity

| Dick Langlois |

This summer I am directing a two-week summer school on “Modularity and Design for Innovation,” July 1-12. I am working closely with Carliss Baldwin, who will be the featured speaker. Other guest speakers will include Stefano Brusoni, Annabelle Gawer, Luigi Marengo, and Jason Woodard.

The school is intended for Ph.D. students, post-docs, and newly minted researchers in technology and operations management, strategy, finance, and the economics of organizations and institutions. The school provides meals and accommodations at the beautiful Hotel Villa Madruzzo outside Trento. Students have to provide their own travel. More information and application here.

This is the fourteenth in a series of summer schools organized at Trento by Enrico Zaninotto and Axel Leijonhufvud. In 2004, I directed one on institutional economics.

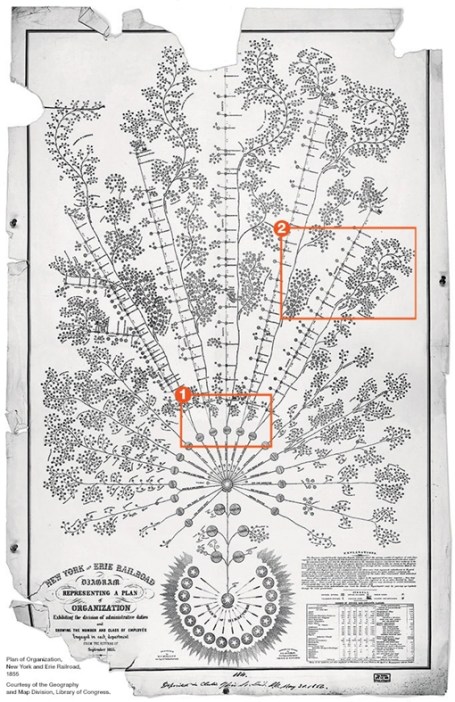

The First Modern Organizational Chart

| Peter Klein |

It was designed in 1854 for the New York and Erie Railroad and reflects a highly decentralized structure, with operational decisions concentrated at the local level. McKinsey’s Caitlin Rosenthal describes it as an early attempt to grapple with “big data,” one of today’s favored buzzwords. See her article, “Big Data in the Age of the Telegraph,” for a fascinating discussion. And remember, there’s little new under the sun (1, 2, 3).

Sequestration and the Death of Mainstream Journalism

| Peter Klein |

Much virtual ink has been spilled over the decline of the mainstream media, measured by circulation, advertising revenue, or a general sense of irrelevance. Usual explanations relate to the changing economics of news gathering and publication, the growth of social media, demographic and cultural shifts, and the like. These are all important but the main issue, I believe, is the characteristics of the product itself. Specifically, news consumers increasingly recognize that the mainstream media outlets are basically public relations services for government agencies, large companies, and other influential organizations. Journalists do very little actual journalism — independent investigation, analysis, reporting. They are told what stories are “important” and, for each story, there is an official Narrative, explaining the key issues and acceptable opinions on these issues. Journalists’ primary sources are off-the-record, anonymous briefings by government officials or other insiders, who provide the Narrative. A news outlet that deviates from the Narrative by doing its own investigation or offering its own interpretation risks being cut off from the flow of anonymous briefings (and, potentially, excluded from the White House Press Corps and similar groups), which means a loss of prestige and a lower status. Basically, the mainstream news outlets offer their readers a neatly packaged summary of the politically correct positions on various issues. In exchange for sticking to the Narrative, they get access to official sources. Give up one, you lose the other. Readers are beginning to recognize this, and they don’t want to pay.

Nowhere is this situation more apparent than the mainstream reporting on budget sequestration. The Narrative is that sequestration imposes large and dangerous cuts — $85 billion, a Really Big Number! — to essential government services, and that the public reaction should be outrage at the President and Congress (mostly Congressional Republicans) for failing to “cut a deal.” You can picture the reporters and editors grabbing their thesauruses to find the right words to describe the cuts — “sweeping,” “drastic,” “draconian,” “devastating.” In virtually none of these stories will you find any basic facts about the budget, which are easily found on the CBO’s website, e.g.:

- Sequestration reduces the rate of increase in federal spending. It does not cut a penny of actual (nominal) spending.

- The CBO’s estimate of the reduction in increased spending between 2012 and 2013 is $43 billion, not $85 billion.

- Total federal spending in 2012 was $3.53 trillion. The President’s budget request for 2013 was $3.59 trillion, an increase of $68 billion (about 2%). Under sequestration, total federal spending in 2013 will be $3.55 trillion, an increase of only $25 billion (a little less than 1%).

- Did you catch that? Under sequestration, total federal spending goes up, just by less than it would have gone up without sequestration. This is what the Narrative calls a “cut” in spending! It’s as if you asked your boss for a 10% raise, and got only a 5% raise, then told your friends you got a 5% pay cut.

- Of course, these are nominal figures. In real terms, expenditures could go down, depending on the rate of inflation. Even so, the cuts would be tiny — 1 or 2%.

- The news media also talk a lot about “debt reduction,” but what they mean is a reduction in the rate at which the debt increases. Even with sequestration, there is a projected budget deficit — the government will spend more than it takes in — during every year until 2023, the last year of the CBO estimates. The Narrative grudgingly admits that sequestration might be necessary to reduce the national debt, but sequestration doesn’t even do that. It’s as if you went on a “dramatic” weight-loss plan by gaining 5 pounds every year instead of 10.

This is all public information, easily accessible from the usual places. But mainstream news reporters can’t be bothered to look is up, and don’t feel any need to, because they have the Narrative, which tells them what to say. Seriously, have you read anything in the New York Times, Washington Post, or Wall Street Journal or heard anything on CNN or MSNBC clarifying that the “cuts” are reductions in the rate of increase? Even Wikipedia, much maligned by the establishment media, gets it right: ” sequestration refers to across the board reductions to the planned increases in federal spending that began on March 1, 2013.” If we have Wikipedia, why on earth would we pay for expensive government PR firms?

NB: See also earlier comments on the mainstream media here and here.

Recent Comments