Posts filed under ‘Management Theory’

New NBER Working Papers

| Peter Klein |

Three new NBER papers likely to interest the O&M crowd. (Aggressive Googlers can probably find ungated versions.)

Railroads and the Rise of the Factory: Evidence for the United States, 1850-70 by Jeremy Atack, Michael R. Haines, and Robert A. Margo

Over the course of the nineteenth century manufacturing in the United States shifted from artisan shop to factory production. At the same time United States experienced a transportation revolution, a key component of which was the building of extensive railroad network. Using a newly created data set of manufacturing establishments linked to county level data on rail access from 1850-70, we ask whether the coming of the railroad increased establishment size in manufacturing. Difference-in-difference and instrument variable estimates suggest that the railroad had a positive effect on factory status. In other words, Adam Smith was right – the division of labor in nineteenth century American manufacturing was limited by the extent of the market.

The Limited Partnership in New York, 1822-1853: Partnerships Without Kinship by Eric Hilt and Katharine O’Banion

In 1822, New York became the first common-law state to authorize the formation of limited partnerships, and over the ensuing decades, many other states followed. Most prior research has suggested that these statutes were utilized only rarely, but little is known about their effects. Using newly collected data, this paper analyzes the use of the limited partnership in nineteenth-century New York City. We find that the limited partnership form was adopted by a surprising number of firms, and that limited partnerships had more capital, failed at lower rates, and were less likely to be formed on the basis of kinship ties, compared to ordinary partnerships. The latter differences were not simply due to selection: even though the merchants who invested in limited partnerships were a wealthy and successful elite, their own ordinary partnerships were quite different from their limited partnerships. The results suggest that the limited partnership facilitated investments outside kinship networks, and into the hands of talented young merchants.

Inside the Black of Box of Ability Peer Effects: Evidence from Variation in Low Achievers in the Classroom by Victor Lavy, Daniele Paserman, and Analia Schlosser

In this paper, we estimate the extent of ability peer effects in the classroom and explore the underlying mechanisms through which these peer effects operate. We identify as low ability students those who are enrolled at least one year behind their birth cohort (repeaters). We show that there are marked differences between the academic performance and behavior of repeaters and regular students. The status of repeaters is mostly determined by first grade; therefore, it is unlikely to have been affected by their classroom peers, and our estimates will not suffer from the reflection problem. Using within school variation in the proportion of these low ability students across cohorts of middle and high school students in Israel, we find that the proportion of low achieving peers has a negative effect on the performance of regular students, especially those located at the lower end of the ability distribution. An exploration of the underlying mechanisms of these peer effects shows that, relative to regular students, repeaters report that teachers are better in the individual treatment of students and in the instilment of capacity for individual study. However, a higher proportion of these low achieving students results in a deterioration of teachers’ pedagogical practices, has detrimental effects on the quality of inter-student relationships and the relationships between teachers and students, and increases the level of violence and classroom disruptions.

Dead Founders

| Lasse Lien |

Here is a link to a very nice paper in the somewhat morbid empirical tradition of using death as a natural experiment. Hans K. Hvide looks at the value of the founder to a newly established firm by examining the performance effects of founder death (or the death of a member of the founding team). Using several empirical tests and an impressive battery of robustness checks, he concludes that the negative impact of founder death is almost unnoticeable on all the classic performance variables. Apparently the importance of the founder is as a discoverer of opportunities and an initiator. As a manger the founder appears to be quite substitutable (on average).

Strong-Man Economics

| Lasse Lien |

Here is an interesting paper from the NBER working paper series. Bolton, Brunnermeier and Veldkamp show that it can be optimal for organizations to hire an irrational manager. Irrational in the sense that the manager is less likely to revise strategy as new information becomes available (i.e. is resolute).

The basic setup is that in the first stage the manager receives a signal about the state of the environment and formulates an initial strategy. In the second stage the organizational members act, deciding how closely the will align their actions to the proposed strategy. The actions of individual members are chosen given their knowledge about the manager’s type and a private signal about the environment. The latter may lead them to anticipate a revision of the strategy. In the third stage the manager receives a second signal about the state of the environment, and in the fourth and final stage the leader decides on the final strategy and payoffs are realized.

The essence of the argument is that the less likely the manager is to revise strategy, the better the coordination of the individual members actions. So there is a time-consistency problem that is reduced when a manager is resolute in the sense of not updating as much as optimal adaptation would suggest, and this is known by followers. The paper also supplies interesting discussions of what happens if the leader can commit to not revising strategy (instead of being a resolute “type”), and the cost of resoluteness if the manager can learn from followers.

One can always quibble about the assumptions made in game-theoretic models. An example here would be the assumption that there is no coordination problem after the manager announces his/her final strategy, only in the period between the initial strategy announcement, and the arrival of the second signal about the environment. But definitely a good read, which nicely captures the trade-off between coordination and adaptation. Hereby recommended (the paper, that is, not the hiring of irrational managers or politicians).

Online Managerial Economics Seminar with Luke Froeb

| Peter Klein |

Luke Froeb, co-author (with Brian McCann) of the excellent MBA text Managerial Economics: A Problem-Solving Approach and co-blogger at Management R&D is conducting an online seminar this Wednesday, “Teaching MBA Students How to Solve Problems Using Economics.” (I can’t bring myself to use the word “webinar.”) All you need to participate is an internet connection and a phone. It’s free but you have to register.

The Coleman Bathtub

| Nicolai Foss |

| Nicolai Foss |

The so-called “Coleman Bathtub” (or “boat”) is one of the most useful expository vehicles for thinking about multi-level issues in social science research. The diagram portrays macro-micro-macro relations as a sort of rhombic figure with causal relations going down from macro (e.g., institutions) to the conditions of individual actions which then give rise to individual actions that in turn aggregate up to macro outcomes. (Check the 1st chapter in James Coleman’s tome, Foundations of Social Theory).

Although the diagram is exceedingly simple, there are substantial potential issues with it, e.g., are the relations depicted in the diagram really causal relations (can macro-entities cause individual actions? Also, I am tempted to adopt the position that ontologically there really aren’t levels, just interacting social actors). Nevertheless, different levels of analysis abound in social science science research, and the Coleman bathtub is often a great eye opener, particularly for students. And I have frequently used it myself in recent research.

I just had my paper with Peter Abell (Professor of Mathematical Sociology, LSE) and Teppo Felin (you know, the orgtheory.net founder), “Building micro-foundations for the routines, capabilities, and performance links,” published in Managerial and Decision Economics. Another plug: with Dana Minbaeva, a HRM specialist in “my” research center, I have written “Governing Knowledge: The Strategic Human Resource Management Dimension.” You can find it here.

Should We Regulate Branding Gurus?

| Nicolai Foss |

Ronald Coase famously argued that if one buys into utilitarian arguments for regulating “the market for goods,” it is hard to present a strong case against regulating the “market for ideas” (here).

I was reminded of Coase’s paper when I received an invitation to an “executive event” from the executive education branch of my School. The event is a presentation by “one of the world’s leading authorities on brand strategy and marketing,” Dr. Erich Joachimsthaler (here he is on Google Scholar), who will present the main messages in a new book co-authored with famous branding guru, David Aaker, Brand Leadership (I cannot locate it on Amazon, so it must be very fresh from the press). Here are some of the things that you can apparently learn from this book:

- Find new growth opportunities in plain sight that are ripe for the picking

- Optimize your existing portfolio to generate sustainable growth without relying on new products

- Innovate beyond product by creating new business models or consumer experiences

- Increase marketing spend effectiveness by directing your dollars to the most relevant aspects of consumers’ daily lives.

The first bullet is particularly lovely. Do you have to be a Chicago finance scholar to deny that there are “new growth opportunities” that are “in plain sight” and “ripe for the picking”? I doubt it. The general question is, how much over the top can you go in terms of advertising your products on the markets for ideas — and should regulators care? While I don’t think there is a general case for regulating these markets, there may exist a Pigovian case for subsidizing books such as this one.

CBS Microfoundations Conference: Knowledge and HRM

| Nicolai Foss |

As O&M readers may know I am the Director of Copenhagen Business School’s Center for Strategic Management and Globalization. As the name indicates we do SIM (strategic and international management), but with a twist: We are specifically interested in the governance dimensions of knowledge processes (knowledge sharing, integration, creation, etc.), and we are specifically interested in micro-foundations for the firm-level concepts that we routinely apply in strategic management and IB (see here for a more detailed characterization). These two themes come together in a conference organized next week (18-19 September) by Dr. Dana Minbaeva, “HRM, Knowledge Processes, and Organizational Performance: In Search of Micro-Foundations.” The papers are online, and many of them should be of potential interest to readers of O&M. I particularly recommend the paper by Joshua Tomsik, Todd Zenger and Teppo Felin (of orgtheory.net fame), “The Knowledge Economy: Emerging Organizational Forms, Micro-Foundations, and Key Human Resource Heuristics.”

Reflections on Cyert and March

| Peter Klein |

The April 2008 issue of JEBO features a symposium on Cyert and March’s 1963 classic, A Behavioral Theory of the Firm (an O&M favorite). The book has been highly influential in organization theory, somewhat influential in behavioral economics, but mostly ignored in the contemporary economics literature on the firm (see here). As Mie Augier and March note in their introduction to the special issue:

As long as the primary focus of the theory of the firm was on the aggregate outcomes of interaction among rational actors, the book’s role in economics was limited. As Cyert and March noted, “Ultimately, a new theory of firm decision making behavior might be used as a basis for a theory of markets, but at least in the short run we should distinguish between a theory of microbehavior, on the one hand, and the micro-assumptions appropriate to a theory of aggregate economic behavior on the other. In the present volume we will argue that we have developed the rudiments of a reasonable theory of firm decision making” (1963, 16).

As interest in economics moved slowly toward greater concern with behavioral micro-assumptions, ideas consistent with Cyert and March (1963) became more prominent ([Kay, 1979], [Day and Sunder, 1996] and [Day, 2002]), although with hesitations and qualifications ([Baumol and Stewart, 1971] and [Williamson and Winter, 1991]). Elements of a behavioral view of the firm can now be found in many modern developments in economics, but especially in transaction cost economics ([Williamson, 1996] and [Williamson, 2002]), evolutionary theory ([Nelson and Winter, 1982], [Nelson and Winter, 2002], [Winter, 1986] and [Dosi, 2004]), and organizational economics (Gibbons, 2003). Behavioral ideas have been elaborated not only in theories of the firm but also in collateral areas of economics, such as strategic management (Rumelt et al., 1991), organization theory (Argote and Greve, 2007), and the psychological foundations of economic choice ([Tversky and Kahneman, 1974], [Kahneman and Tversky, 1979] and [Camerer et al., 2004]). Ideas of bounded rationality, conflict, learning, and routines are now commonplace, as is the general idea that economic behavior is guided by principles of human behavior. Although those ideas have many ancestors, A Behavioral Theory of the Firm probably contributed some modest amount of DNA.

Of particular interest to the O&M crowd are “Outlines of a Behavioral Theory of the Entrepreneurial Firm” by Dew, Read, Sarasvathy, and Wiltbank; “Realism and Comprehension in Economics: A Footnote to an Exchange Between Oliver E. Williamson and Herbert A. Simon” by Augier and March; and “Unpacking Strategic Alliances: The Structure and Purpose of Alliance versus Supplier Relationships” by Mayer and Teece.

McNamara on Management

| Peter Klein |

From Abraham Zaleznik in HBS Working Knowledge (via Marshall Jevons):

[Robert S. McNamara] was a brilliant student at the University of California and at Harvard Business School, where he became a member of the HBS faculty. McNamara was a devotee of managerial control, an expertise he applied in his work at the Ford Motor Company and later at the Department of Defense as secretary in President John F. Kennedy’s cabinet.

His mantra was measurement. As secretary of defense, McNamara developed, along with key subordinates, including Robert Anthony of the HBS control faculty, long-range procurement cycles. He even tried to get the U.S. Navy to subscribe to a common aircraft for the three branches of the military. The Navy refused to go along, since this branch was concerned about aircraft operating from carriers.

McNamara urged field commanders in Vietnam to apply measurement to enemy losses, but did not realize until it was too late that the measurements were unreliable to assess enemy losses. The most reliable assessments came from correspondents like Neil Sheehan and David Halberstam. McNamara published a book years after he retired to reassess the Vietnam War and his role in it as secretary of defense. His main theme was the failure to examine critically the assumptions leading to U.S. involvement in this disaster. Editorial writers took no pains to spare McNamara’s feelings.

The moral I took away from his story is to avoid the perils of the fox and its reliance on a single belief, in this case measurement, and the technology of control.

For more on McNamara’s management philosophy and experiences, Deborah Shapley’s 1992 biography Promise and Power is pretty good. I also recommend The Whiz Kids: Ten Founding Fathers of American Business — and the Legacy They Left Us by John Byrne. As these books point out, McNamara was not a pioneer in this area but a follower of Tex Thornton, head of the US Army’s Statistical Control Group in WWII and later CEO of Litton Industries. It was Thornton who brought McNamara and the rest of his “Whiz Kids,” as a group, to Ford in 1945. Harold Geneen, the most famous “management-by-the-numbers” guy, was not part of this group but shared much of Thornton’s philosophy. (See Robert Sobel’s Rise and Fall of the Conglomerate Kings.)

Random Thoughts from the AoM

| Peter Klein |

Back now from the AoM conference in Anaheim. Random thoughts:

1. The Critical Management Studies Division (yes, it really exists) featured, as a keynote speaker, none other than Ward Churchill, former professor of ethnic studies at the University of Colorado (fired in 2007 for professional misconduct). His talk: “On the Banality of Managerial Efficiency: The ‘Eichman Question’ Revisited.” Apparently the Late Unpleasantness (1, 2) did not disqualify him from this eminent academic honor. I did not attend the talk but was told he was “impressive.”

BTW, if you’re wondering about this division of the Academy, look no farther than the CMS website:

The Critical Management Studies Division is a forum within the Academy for the expression of views critical of unethical management practices and exploitative social order. Our premise is that structural features of contemporary society, such as the profit imperative, patriarchy, racial inequality, and ecological irresponsibility often turn organizations into instruments of domination and exploitation. Driven by a shared desire to change this situation, we aim in our research, teaching, and practice to develop critical interpretations of management and society and to generate radical alternatives. Our critique seeks to connect the practical shortcomings in management and individual managers to the demands of a socially divisive and ecologically destructive system within which managers work.

2. You know how all stereotypes are based on elements of truth? I noticed that the receptions hosted by groups and organizations dominated by economists (such as the BPS Division) tended to have cash bars, while those dominated by psychologists and sociologists (e.g., anything to do with organizational behavior) tended to have open bars. (more…)

A Note to My Undergraduate Students

| Peter Klein |

From a former student:

I was in your Managerial Economics back in Spring 2005. I guess I actually learned something and remembered it. I am going back to school for my MBA and I was able to test out of my basic economics class using the knowledge I gained in your class. Since I actually paid attention to you talking about game theory, I was able to save myself from taking an extra graduate class.

Pay attention now, save $$$ later!

O&M at the AoM

Ah, Los Angeles . . . land of “tattoos, breast implants, bleached hair, and vacuous egos,” as Nicolai recently wrote on Facebook. And then there are the people not in town for the Academy of Managment meeting!

As readers may know, the AoM is meeting this week in Anaheim. The O&M crowd is well represented, as usual. You can search the online program for your favorite person, subject, or interest area. Below are some of the sessions involving O&Mers, past and present: (more…)

Top Management Scholars, Journals, and Universities

| Peter Klein |

Rankings, rankings, more rankings. . . . If you like to bibliometric analysis of individual researchers, journals, and universities you’ll find more than you can handle in “Scholarly Influence in the Field of Management: A Bibliometric Analysis of the Determinants of University and Author Impact in the Management Literature in the Past Quarter Century” by Philip Podsakoff, Scott MacKenzie, Nathan Podsakoff, and Daniel Bachrach (Journal of Management 34, no. 4 (2008): 641-720). Over 25,000 individual scholars are reviewed, their institutions evaluated, journal impact factors computed, and numbers crunched hither and yon. Some qualitative conclusions:

The findings showed that (a) a relatively small proportion of universities and scholars accounted for the majority of the citations in the field; (b) total publications accounted for the majority of the variance in university citations; (c) university size, the number of PhDs awarded, research expenditures, and endowment assets had the biggest impact on university publications; and (d) total publications, years in the field, graduate school reputation, and editorial board memberships had the biggest effect on a scholar’s citations.

Neuroeconomics and the Firm

| Peter Klein |

I’m not a big fan of neuroeconomics — Gul and Pesendorfer’s critique seems about right to me — but if you like that field you may be interested in this call for book chapters:

Neuroeconomics and the Firm

Editors:

Mellani Day

Angela Stanton

Isabell WelpeHow can we take advantage of neuroeconomics to inform organizations? Neuroscience can provide us with ways to understand causal relationships; it enables us to identify the biological drivers of beliefs, opportunity perception, opportunity analysis, risk-aversion or risk-seeking, motivation, incentives and reward mechanisms; in other words, we can map the pre-decisional dynamics of the human brain. Neuroeconomics has yielded important new insights and may provide powerful new ways of looking at the firm. (more…)

Technology and Firm Size and Organization

| Peter Klein |

As a New Economy skeptic (1, 2, 3, 4) I worry about sweeping claims that information technology has rendered obsolete the large, vertically integrated, publicly held corporation and its managerial hierarchy. Such claims suffer from two problems: First, they tend to be thinly documented — evidence on the economy-wide distribution of organizational forms is largely fragmentary and anecdotal. Second, they usually exaggerate what’s new about those changes that we can document. As I wrote in my review of Yochai Benkler’s The Wealth of Networks:

Benkler proposes social production as an alternative to the traditional organizational modes of “market” and “hierarchy,” to use Oliver Williamson’s terminology. Indeed, open-source production differs in important ways from spot-market interaction and production within the private firm. But here, as elsewhere, Benkler tends to overstate the novelty of social production. Firms, for example, have long employed internal markets, delegated decision rights throughout the organization, formed themselves into networks, clusters, and alliances, and otherwise taken advantage of openness and collaboration. There exists a variety of organizational forms that proliferate within the matrix of private property rights. Peer production is not new; the relevant question concerns the magnitude of the changes.

Here, the book suffers from a problem common to others in this genre. Benkler provides a wealth of anecdotes to illustrate the revolutionary nature of the new economy but little information on magnitudes. How new? How large? How much? Cooperative, social production itself is hardly novel, as any reader of “I, Pencil,” can attest. Before the web page, there was the pamphlet; before the Internet, the telegraph; before the Yahoo directory, the phone book; before the personal computer, electric service, the refrigerator, the washing machine, the telephone, and the VCR. In short, such breathlessly touted phenomena as network effects, the rapid diffusion of technological innovation, and highly valued intangible assets are not really really new. (Tom Standage’s history of the telegraph and its own revolutionary impact, The Victorian Internet [New York: Walker & Company, 1998], is well worth reading in this regard.)

A new paper by Giovanni Dosi, Alfonso Gambardella, Marco Grazzi, and Luigi Orsenigo, “Technological Revolutions and the Evolution of Industrial Structures: Assessing the Impact of New Technologies upon the Size and Boundaries of Firms,” looks at the empirical evidence more systematically and concludes that the effect of information technology on firm size and organization is real, but modest: (more…)

The Ecconomics of Organizing Economists

| Peter Klein |

Most regulatory agencies are staffed by a mix of attorneys and economists. Members of these groups do not always play well together. How, then, should such an agency be organized — functionally, putting the economists in a single unit, reporting to a chief economist, or divisionally, spreading the economists throughout divisions organized by legal issue, industry sector, geographic region, etc. and having them report to an attorney in charge of each division? An interesting application of the U-form versus M-form problem posed by Chandler (1962).

An analysis of organizational structure at US and European competition agencies by Luke Froeb, Paul Pautler, and Lars-Hendrik Roller (via Dan Sokol) finds that

the main advantage of a functional organization is higher quality economic analysis while the disadvantage is that the analysis may not be focused on legal questions of concern, and is less easily communicated to the ultimate decision makers. Likewise, the advantages of a divisional organization are decentralized, and faster, decision making; however, the quality of the economic analysis is likely to be lower and can result in less information reaching the ultimate decision makers.

Froeb, Pautler, and Roller suggest that hybrid forms, such as (a) functional organizations with strong horizontal links between economists and attorneys or (b) divisional organizations with strong vertical links between economists and attorneys, and managers trained in both law and economics, are best.

My own experience at the CEA confirms the importance of both the vertical and horizontal links. We economists were organized into a focused unit for major projects like the Economic Report of the President but were also assigned to ad hoc, inter-Agency teams working on specific policy issues (I dealt with spectrum auctions, the pricing of air traffic control, and foreign ownership of domestic telecom assets, among other things). I was typically the lone economist (though hardly the nerdiest member) on each team.

Russ Coff Guest Blogging at orgtheory.net

| Peter Klein |

Russ Coff, whose work is popular in these parts, is guest blogging over at orgtheory.net. Look for some good stuff in the coming weeks.

Update: Here’s his first post.

Stop Using Management Buzzwords

| Peter Klein |

That’s the command to town and village officials from Britain’s Local Government Association, which urges its members to dump trite words and phrases like core values, evidence base, facilitate, fast-track, holistic, level playing field, process driven, quick hit, and my personal favorite, predictors of beaconicity (no idea what it means). Here’s the list, and here’s the CNN story (via Josh). From CNN:

The list includes the popular but vague term “empowerment;” “coterminosity,” a situation in which two organizations oversee the same geographical area; and “synergies,” combinations in which the whole is greater than the sum of its parts.

Officials were told to ditch the term “revenue stream” for income, as well as the imprecise “sustainable communities.” The association also said councils should stop referring to local residents as “customers” or “stakeholders.”

The association’s chairman, Simon Milton, said officials should not “hide behind impenetrable jargon and phrases.”

Business-school educators, please take note!

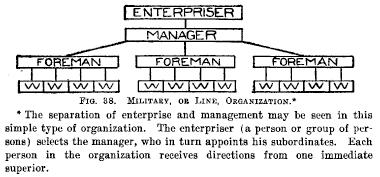

Organizational Charts from 1915

| Peter Klein |

These images come from Frank Fetter’s second principles treatise, his Economic Principles (1915), which included chapters on “Enterprise” and “Management.” Note that at the top of the hierarchy sits the “enterpriser,” a term Fetter borrowed from Frederick Hawley), instead of “entrepreneur” or “adventurer,” both of which were then in common use to describe the business person. (Adventurer meant simply “one who undertakes a venture.”) Hawley preferred enterpriser because it suggested not simply management, but “responsibility,” or “the subjection [of one’s actions] to the results of production” (Hawley, 1908, p. 470). This is essentially the concept of entrepreneurship proposed in recent Foss-Klein papers (some of which you can find here), namely judgmental decision-making about the deployment of resources in the face of Knightian uncertainty.

Reliving the 1980s

Peter Klein |

I recently watched the new Rambo film, an entertaining spectacle of blood and gore (for those who enjoy that sort of thing). The last few years have brought back several 1980s-era action heroes after long absences, not only Rambo but also Rocky Balboa, John McClane, the Terminator, and of course Indiana Jones.

We posted a while back on the golden decade of the 1970s, a fantastically productive period for research in organizational economics. How about bringing back the 1980s? Not the mullet, but the great works in organizational economics, strategy, entrepreneurship, and related subjects that appeared in that decade. Here are some of my favorites, listed chronologically. What are yours? (more…)

Recent Comments