And If You Can’t Teach, Teach Gym

| Peter Klein |

Kate Maxwell, writing at Growthology, is concerned about the distance between those who do entrepreneurship and those who teach or research entrepreneurship:

In my reading of the entrepreneurship literature I have been struck by the large gap between entrepreneurs and people who study entrepreneurship. The group of people who self select into entrepreneurship is almost entirely disjoint from the group of people who self select to study it. Such a gap exists in other fields to greater and lesser degrees. Sociologists, for instance, study phenomenon in which they are clearly participants whereas political scientists are rarely career politicians but are often actors in political systems.

But in the case of entrepreneurship the gap is cause for concern. My sense is that all too often those studying entrepreneurship don’t understand, even through exposure, the messy process of creating a business, nor, due to selection effects, are they naturally inclined to think like an entrepreneur might.

I agree entirely with this description, but am not sure I understand the concern. Kate seems to assume a particular concept of entrepreneurship — the day-to-day mechanics of starting and growing a business — that applies only to a fraction of the entrepreneurship literature. Surely one can study the effects of entrepreneurship on economic outcomes like growth and industry structure without “thinking like an entrepreneur.” Same for antecedents to entrepreneurship such as the legal and political environment, social and cultural norms, the behavior of universities, etc. Even more so, if we treat entrepreneurship as an economic function (alertness, innovation, adaptation, or judgment) rather than an employment category or a firm type, then solid training in economics and related disciplines seems the main prerequisite for doing good research.

Of course, this doesn’t mean that entrepreneurship scholars shouldn’t talk to entrepreneurs or study their lives and work. Want to know how if feels to throw the winning Superbowl pass? Ask Tom Brady or Eli Manning. The stat sheet won’t tell you that. But this doesn’t mean that only ex-NFL players can be competent announcers, analysts, sportswriters, etc. Similarly, I like to read about food, and have enjoyed the recent memoirs of great chefs like Jacques Pépin and Julia Child. These first-hand accounts are full of unique insights and colorful observations. But there are plenty of great books on the restaurant industry, on the relationship between food and culture, on culinary innovation, etc. by authors who couldn’t cook their way out of a paper bag.

What do you think?

Why I Avoid Bourdieu: #2,538 in a Series

| Peter Klein |

I have little to add to this press release, summarizing a call by sociologists to treat the individual and social disease of failing to take climate change seriously:

LONDON — (March 26, 2012) — Resistance at individual and societal levels must be recognized and treated before real action can be taken to effectively address threats facing the planet from human-caused contributions to climate change.

That’s the message to this week’s Planet Under Pressure Conference by a group of speakers led by Kari Marie Norgaard, professor of sociology and environmental studies at the University of Oregon. . . .

“We find a profound misfit between dire scientific predictions of ongoing and future climate changes and scientific assessments of needed emissions reductions on the one hand, and weak political, social or policy response on the other,” Norgaard said. Serious discussions about solutions, she added, are mired in cultural inertia “that exists across spheres of the individual, social interaction, culture and institutions.”

“Climate change poses a massive threat to our present social, economic and political order. From a sociological perspective, resistance to change is to be expected,” she said. “People are individually and collectively habituated to the ways we act and think. This habituation must be recognized and simultaneously addressed at the individual, cultural and societal level — how we think the world works and how we think it should work.”

In their paper, Norgaard and co-authors Robert Brulle of Drexel University in Philadelphia and Randolph Haluza-DeLay of The King’s University College in Canada draw from the work of French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu (1930-2002) to describe social mechanisms that maintain social stability or cultural inertia in the face of climate change at the three levels. . . .

I note that the lead author recently published Living in Denial: Climate Change, Emotions, and Everyday Life (MIT Press, 2011), which sounds like a reasonable, balanced, and objective look at the climate-change debate.

CFP: Bricolage in Art and Entrepreneurship

| Peter Klein |

| Peter Klein |

Bricolage — doing the best you can with the materials on hand, rather than choosing and end and getting the resources you need — is an important concept in the contemporary entrepreneurship literature. Garud and Karnøe’s influential 2003 paper on the Danish wind power industry helped bring bricolage into the mainstream, and it has important parallels with effectuation and other approaches to entrepreneurship that emphasize experimentation and incremental learning.

The University of Missouri’s Department of Romance Languages and Literatures is hosting an interdisciplinary conference, 12-13 November 2012, on bricolage in art and entrepreneurship, focusing on the work of Ediciones Vigía, a unique artists’ collective that produces limited edition handmade books by Cuban and international authors and musicians. Participants will come not only from the humanities, education, and journalism, but also economics, management, and entrepreneurship. Among the featured speakers are Ivo Zander, who recently co-edited a book on Art Entrepeneurship, and Sharon Alvarez.

O&M readers interested in the relationship between business and the arts, the parallels between artistic creativity and entrepreneurial creativity, the economic organization of artist networks, and related issues should check it out. The full call for papers, along with related information, is below the fold.

The Socialist Car

| Peter Klein |

| Peter Klein |

I blogged previously about Lewis Siegelbaum’s 2008 book Cars for Comrades: The Life of the Soviet Automobile (or, more precisely, Perry Patterson’s EH.Net review). So I need to say something about the follow up, The Socialist Car: Automobility in the Eastern Bloc (Cornell University Press, 2011), an essay collection edited by Siegelbaum. Once again, here’s Patterson:

As was true for Cars for Comrades, this book takes the modern upper-middle-class Western reader far from the contemporary world where drivers need not know what’s “under the hood,” where synthetic oil might not need attention for 15,000 miles or more, and where long-standing institutions for finance, distribution and service of vehicles are seemingly ubiquitous. Rather, this is a world where two-stroke engines are designed for easy (and frequent) self-service, new car owners are required to install windshield wipers, and new automobiles are provided with extensive repair kits and instructions for disassembly. This world is also one where private automobiles – and even socially-owned trucks – represent potential threats to the Soviet-style socialist undertaking by providing opportunities for generating illegal incomes and diverting resources toward consumption. At the core of the rich set of stories contained here are the compromises that everyday citizens, urban planners, and Party officials routinely made as the powerful forces associated with the automobile became more and more apparent throughout the socialist bloc. In addition, the examples presented in this eleven-chapter volume say much about the increasingly complex information flows required and implied by automobiles that became more and more technically complex over time.

Speaking of EH.net, the performativity crowd may get a kick out of another recent review, Bruce Carruthers’s discussion of Carl Wennerlind, Casualties of Credit: The English Financial Revolution, 1620-1720 (Harvard University Press, 2011). Notes Carruthers: “It was not simply that early modern capital markets evolved, that financial systems developed, or that English economic institutions changed. These critical transformations were accompanied and even shaped by the analyses offered by people who witnessed the events of the time.”

Capabilities and Organizational Economics Once More

| Nicolai Foss |

As readers of this blog will know, the dialogue between the firm capabilities literature and organizational economics has a long history in management research and economics. Co-blogger Dick Langlois has been an important contributor in this space. The forty years long discussion (dating it from George B. Richardson’s 1972 hint that his newly coined notion of capability is complementary to Coasian transaction cost analysis) has proceeded through several stages. Thus, the initial wave of capabilities theory (i.e., beginning to mid-1990s) was strongly critical of organizational economic. This gave way to a recognition that perhaps the two perspectives were complementary in a more additive manner. Thus, whereas capabilities theory provided insight in which assets firms need to access to compete successfully, organizational economics provide insight into how such access is contractually organized. However, increasingly work has stressed deeper relations of complementarity: Capabilities mechanisms are intertwined with the explanatory mechanisms identified by organizational economists.

In a paper, “The Organizational Economics of Organizational Capability and Heterogeneity: A Research Agenda,” that is forthcoming as the Introduction to a special issue of Organization Science on the the relation between capabilities and organizational economics ideas, Nick Argyres, Teppo Felin, Todd Zenger and I argue, however, that the discussion has been lopsided—hardly qualifying as a real debate—and that a reorientation is necessary.Specifically, the terms of the discussion have largely been defined by capabilities theorists. Part of the explanation for this dominance is that capability theorists have had a rhetorical advantage, because everyone seems to have accepted that organizational economics has very little to say about organizational heterogeneity. We argue that this rests on a misreading of organizational economics: while it is true that organizational economics was not (directly) designed to address and explain organizational heterogeneity, this does not imply that the theory is and must remain silent about such heterogeneity. In fact, we discuss a number of ways in which organizational economics is quite centrally focused on explaining organizational heterogeneity. Specifically, we argue that organizational economics provides guidance around how organizational design and boundaries facilitate the formation of knowledge, insight, and learning that are central to the heterogeneity of firms. We also demonstrate how efficient governance can itself be a source of competitive heterogeneity. We thus call on organizational economists to actively and vigorously enter the discussion, turning something closer to a monologue into real dialogue. (more…)

Economists, (Hard) Data, and (Soft) Data

| Nicolai Foss |

Economists have typically been suspicious of data generated by (mail, telephone) surveys and interviews, and have idolized register data. The former are soft and mushy data, the latter are hard and serious ones. I have always been a bit sceptical regarding whether the traditional economist’s suspicion of soft data is really that well-founded; after all, the statistical agencies of the world and other government institutions that are in the business of data collection are populated by fallible individuals and respondents are the same ones that respond to, say, a mail survey conducted by Prof. N. J. Foss, PhD. (Having recently conducted a major data collection effort with a public statistical agency, my skepticism has dramatically increased!)

The argument is sometimes made that there may be a legal duty to respond to the queries of a government agency and this means a high response rate and accurate reporting. However, it appears that we know rather little about the accuracy of data generated in this way, and it is quite conceivable that measurement error is high, exactly because the provision of data is “forced” (those anarcho-capitalist types out there may delight in providing errorneous data!). The serious content of the traditional economist’s prejudice is rather, I think, that surveys often have respondents reacting to subjective scales rather than providing absolute numbers. This is a warranted concern, but not a critique of surveys and interviews per se, because these methods do not imply commitment to subjective scales per se.

As a rule register data are not available that can be used to address numerous interesting issues in organizational economics, labor economics, productivity research and so on. Scholars working on these issues have to resort to those softy surveys and interviews that have been the workhorses of business school faculty for decades. This is a new recognition in economics. Case in point: A recent paper by Nicholas Bloom and John Van Reenen, “New approaches to surveying organizations.” There is absolutely nothing, I submit, in this short, well-written paper that would surprise virtually any empirically oriented business school professor (i.e., virtually all bschool professors) to whom this would not be anything “new” at all, but rather old hat.

This is not a critique of Profs. Bloom and Van Reenen at all (on the contrary, it is excellent that they educate their economist colleagues in this way). It is just striking and a little bit amusing, however, that we have had to wait until 2010 until empirical approaches that have been mainstream in management research for decades reach the pages of the American Economic Review.

Lazear and Spletzer on Creative Destruction

| Peter Klein |

What labor economists call “churn” is an important part of creative destruction, the combining and recombining of productive resources as business entities appear and disappear. New paper:

Hiring, Churn and the Business Cycle

Edward P. Lazear, James R. Spletzer

NBER Working Paper No. 17910

Issued in March 2012Churn, defined as replacing departing workers with new ones as workers move to more productive uses, is an important feature of labor dynamics. The majority of hiring and separation reflects churn rather than hiring for expansion or separation for contraction. Using the JOLTS data, we show that churn decreased significantly during the most recent recession with almost four-fifths of the decline in hiring reflecting decreases in churn. Reductions in churn have costs because they reflect a reduction in labor movement to higher valued uses. We estimate the cost of reduced churn to be $208 billion. On an annual basis, this amounts to about .4% of GDP for a period of 3 1/2 years.

First Copies of the New Book

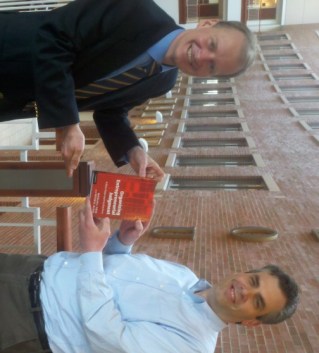

Nicolai was in town yesterday to deliver the 2012 Sherlock Hibbs Distinguished Lecture in Economics and Business, and he gave a terrific talk about “open entrepreneurship,” the application of concepts and principles from the open innovation literature to the discovery, evaluation, and exploitation of entrepreneurial opportunities. Upon returning to my office after the lecture, I found a surprise waiting for me: the first hardcopies of our new book, Organizing Entrepreneurial Judgment: A New Approach to the Firm (Cambridge University Press, 2012). As both authors happened to be together, we preserved the moment for posterity.

You can order today on Amazon’s UK site (or pre-order on the US site, which shows a publication date of 30 April). You can order directly from Cambridge (UK or US).

A brief description and some endorsements are below the fold.

NB: Tomorrow Nicolai is giving the Hayek Lecture at the Austrian Scholars Conference, which you can watch live online.

Update: O&M readers can order directly from Cambridge and receive a 20% discount! Use this link.

Hayek on Schumpeter on Methodological Individualism

| Peter Klein |

Our QOTD comes from the 2002 version of Hayek’s “Competition as a Discovery Procedure.” (Thanks to REW for the inspiration.) Hayek delivered two versions of the lecture, both in 1968, one in English and one in German. The former appeared in Hayek’s 1978 collection New Studies in Philosophy, Politics, Economics, and the History of Ideas, and is the version most familiar to English-speaking scholars. In 2002 the QJAE published a new English translation of the German version which includes two sections (II and VII) omitted from the earlier English version. In this passage from section II Hayek distinguishes macroeconomics (“macrotheory”) from microeconomics (“microtheory”):

About many important conditions we have only statistical information rather than data regarding changes in the fine structure. Macrotheory then often affords approximate values or, probably, predictions that we are unable to obtain in any other way. It might often be worthwhile, for example, to base our reasoning on the assumption that an increase of aggregate demand will in general lead to a greater increase in investment, although we know that under certain circumstances the opposite will be the case. These theorems of macrotheory are certainly valuable as rules of thumb for generating predictions in the presence of insufficient information. But they are not only not more scientific than is microtheory; in a strict sense they do not have the character of scientific theories at all.

In this regard I must confess that I still sympathize more with the views of the young Schumpeter than with those of the elder, the latter being responsible to so great an extent for the rise of macrotheory. Exactly 60 years ago, in his brilliant first publication, a few pages after having introduced the concept of “methodological individualism” to designate the method of economic theory, he wrote:

If one erects the edifice of our theory uninfluenced by prejudices and outside demands, one does not encounter these concepts [namely “national income,” “national wealth,” “social capital”] at all. Thus we will not be further concerned with them. If we wanted to do so, however, we would see how greatly they are afflicted with obscurities and difficulties, and how closely they are associated with numerous false notions, without yielding a single truly valuable theorem.

The reference is to Schumpeter’s 1908 book, Das Wesen und der Hauptinhalt der theoretischen Nationalökonomie which, to my knowledge, has never been translated (though an excerpt, and some commentary, are here). For more on the different versions of Hayek’s essay see here and here.

NB: Krugman blogged over the weekend about microfoundations, offering a remarkably (sic) shallow and misguided critique based on what Hayek would call the scientistic fallacy. E.g.: “meteorologists were using concepts like cold and warm fronts long before they had computational weather models, because those concepts seemed to make sense and to work. Why, then, do some economists think that concepts like the IS curve or the multiplier are illegitimate because they aren’t necessarily grounded in optimization from the ground up?” Ugh.

Murray Rothbard Day

| Peter Klein |

Today would have been Murray Rothbard’s 86th birthday. Rothbard is widely (and rightly) regarded as the father of the modern libertarian movement, and a driving force behind the “Austrian” revival in the US, beginning in the late 1950s. For this occasion I hope I can be forgiven a bit of personal reminiscence, courtesy of a brief excerpt from the introduction to my 2010 book, The Capitalist and the Entrepreneur:

Today would have been Murray Rothbard’s 86th birthday. Rothbard is widely (and rightly) regarded as the father of the modern libertarian movement, and a driving force behind the “Austrian” revival in the US, beginning in the late 1950s. For this occasion I hope I can be forgiven a bit of personal reminiscence, courtesy of a brief excerpt from the introduction to my 2010 book, The Capitalist and the Entrepreneur:

As a college senior, I was thinking about graduate school—possibly in economics. By pure chance, my father saw a poster on a bulletin board advertising graduate-school fellowships from the Ludwig von Mises Institute. (Younger readers: this was an actual, physical bulletin board, with a piece of paper attached; this was in the dark days before the Internet.) I was flabbergasted; someone had named an institute after Mises? I applied for a fellowship, received a nice letter from the president, Lew Rockwell, and eventually had a telephone interview with the fellowship committee, which consisted of Murray Rothbard. You can imagine how nervous I was the day of that phone call! But Rothbard was friendly and engaging, his legendary charisma coming across even over the phone, and he quickly put me at ease. (I also applied for admission to New York University’s graduate program in economics, which got me a phone call from Israel Kirzner. Talk about the proverbial kid in the candy store!) I won the Mises fellowship, and eventually enrolled in the economics PhD program at the University of California, Berkeley, which I started in 1988.

Before my first summer of graduate school, I was privileged to attend the “Mises University,” then called the “Advanced Instructional Program in Austrian Economics,” a week-long program of lectures and discussions held that year at Stanford University and led by Rothbard, Hans-Hermann Hoppe, Roger Garrison, and David Gordon. Meeting Rothbard and his colleagues was a transformational experience. They were brilliant, energetic, enthusiastic, and optimistic. Graduate school was no cake walk—the required core courses in (mathematical) economic theory and statistics drove many students to the brink of despair, and some of them doubtless have nervous twitches to this day—but the knowledge that I was part of a larger movement, a scholarly community devoted to the Austrian approach, kept me going through the darker hours.

I go on to discuss Oliver Williamson’s influence on my research program. Later I include Rothbard among my dedicatees:

Murray Rothbard, the great libertarian polymath whose life and work played such a critical role in the modern Austrian revival, dazzled me with his scholarship, his energy, and his sense of life. Rothbard is widely recognized as a great libertarian theorist, but his technical contributions to Austrian economics are not always appreciated, even in Austrian circles. In my view he is one of the most important contributors to the “mundane” Austrian analysis described above.

New Article from Langlois

| Peter Lewin |

Since it hasn’t been mentioned here yet, I would like to take the liberty of recommending a great “how it all fits together” article by Dick Langlois forthcoming in the Review of Austrian Economics, entitled “The Austrian Theory of the Firm: Retrospect and Prospect.” I just reread it with great pleasure (I saw it a few years ago at a seminar). With characteristic Langlois ease (or so it seems) Dick weaves the connections between Coase, Hayek, Lachmann, Richardson, Pensrose, Chandler, Foss, Langlois, and others to provide a very clear picture.

Computers in Higher Education, 1960s Edition

| Peter Klein |

An illuminating passage from James Ridgeway’s 1968 book The Closed Corporation: American Universities in Crisis, a scathing critique of the university-military-industrial complex. Note the cameo by Jim March:

[University of California officials Ralph W.] Gerard and [R. Dan] Tschirgi are computer fetishists who insist information is knowledge, and that the function of a university is to provide information.

In 1963 and 1964 Chancellor David G. Aldrich, Jr., at Irvine, and Gerard got IBM interested in setting up programs there. The company agreed to install a 1400 system and to supply staff and engineers. An IBM employee, Dr. J. A. Kearns, came along to head the project and was given a part-time appointment at the Graduate School of Administration. The idea was to see whether the computer could be used as a library, for various administrative functions and for teaching.

Gerard paints a glowing picture. He says that one half of the students on the Irvine campus spend at least one hour a week on the computer, and that computers are used in teaching biology, mathematics, economics, sociology and psychology.

After speaking with Gerard, I went along to see the computer in action, and ran into a senior staff man who told me in a jaundiced manner that it wasn’t operating because they couldn’t make the new IBM 360 system work right. This gentleman was exceedingly glum about the possibilities of very many students learning much of anything on the Irvine computers. So was the dean of Social Sciences, James G. March. When I asked him about the use of the machine to teach sociology, he replied grimly that all the computer did was to print out some basic definitions in an introductory course, which, as he pointed out, one could get just as well from reading a book. He went on to say that a minute portion of any introductory course was on a computer, that students spent little time on them, and that most of the time was taken up programming them. March said the difficulty was to devise a system which could answer questions rather than ask them. The most one could really expect was to have a machine pose a problem to the student, who could then go ahead an answer it on his own.

The tech described here is dated but the book itself still packs a punch. In the late 1906s concerns about the close relationships between the federal government (particularly the Pentagon), public research universities, and industry (particularly defense contractors) were new. Now we take for granted that a primary task of the research university is to produce “applied” research in close cooperation with government and industry sponsors, to commercialize its scientific discoveries, to train students for industry, and so on. But this is a fairly recent — mid-20th century — development, and not an obviously desirable one.

Evil Tw-Lin

| Peter Klein |

Jeremy Freese to his fellow sociologists:

Jeremy Freese to his fellow sociologists:

Jeremy Lin’s favorite course at Harvard was Sociology 128: Methods of Social Science Research. Nevertheless, he majored in economics, so your department cannot staple his face to its “What Can You Do With A Sociology Major?” poster.

(If you don’t get the headline, ask the kittehs.)

Zenger, Felin, and Bigelow on “Theories of the Firm-Market Boundary”

| Peter Klein |

Here’s a nice review and synthesis of “Theories of the Firm-Market Boundary” by Todd Zenger, Teppo Felin, and Lyda Bigelow, just out in the Academy of Management Annals.

A central role of the entrepreneur-manager is assembling a strategic bundle of complementary assets and activities, either existing or foreseen, which when combined create value for the firm. This process of creating value, however, requires managers to assess which activities should be handled by the market and which should be handled within hierarchy. Indeed, for more than 40 years, economists, sociologists and organizational scholars have extensively examined the theory of the firm’s central question: what determines the boundaries of the firm? Many alternative theories have emerged and are frequently positioned as competing explanations, often with no shortage of critique for one another. In this paper, we review these theories and suggest that the core theories that have emerged to explain the boundary of the firm commonly address distinctly different directional forces on the firm boundary — forces that are tightly interrelated. We specifically address these divergent, directional forces — as they relate to organizational boundaries — by focusing on four central questions. First, what are the virtues of markets in organizing assets and activities? Second, what factors drive markets to fail? Third, what are the virtues of integration in organizing assets and activities? Fourth, what factors drive organizations to fail? We argue that a complete theory of the firm must address these four questions and we review the relevant literature regarding each of these questions and discuss extant debates and the associated implications for future research.

Lots of good stuff here, especially in integrating economic and sociological perspectives on boundary (I guess all that time Teppo spends over there has influenced his thinking).

Hoisted from the Comments: Journal Impact Factors

| Peter Klein |

An old post of Nicolai’s on journal impact factors is still attracting attention. Two recent comments are reproduced here so they don’t get buried in the comments.

Bruce writes:

There is an interesting paper by Joel Baum on this, “Free Riding on Power Laws: Questioning the Validity of the Impact Factor as a Measure of Research Quality in Organization Studies,” Organization 18(4) (2011): 449-66. He does a nice analysis of citations, and shows (what many of us suspected) that citations are highly skewed to a small subset of articles, so the idea of an impact factor which is based on a mean citation rate is erroneous. He concludes that “Impact Factor has little credibility as a proxy for the quality of eitehr organization studies journals of the articles they publish, resulting in attributions of journal or article quality that are incorrect as much or more than half the time. The clear implication is that we need to cease our reliances on such non-scientific, quantitative characterisation to evaluate the quality of our work.”

To which Ram Mudambi responds:

This analysis was already done in a paper we wrote in 2005, finally now published in Scientometrics.

We have the further and stronger result that in many years, the top 10 percent of papers in A- journals like Research Policy outperform the top 10 percent of papers in A journals like AMJ.

So it is the paper that matters, NOT the journal in which it was published. Evaluating scholars on the basis of where they have published is pretty meaningless. Some years ago, we had a senior job candidate with EIGHTEEN real “A” publications — it turned out he had only 118 total citations on Google scholar. So his work was pretty trivial, even though it appeared in top journals.

See also the good twin blog for further discussion.

New ebooks — Knowledge on the Cheap

| Peter Klein |

| Peter Klein |

Google’s ebookstore now contains deeply discounted versions of several Edward Elgar books (which are usually priced for library use), including my Elgar Companion to Transaction Cost Economics ($48) and the Foss-Klein product Entrepreneurship and the Firm: Austrian Perspectives on Economic Organization ($31.20). Nicolai’s greatest hits collection Knowledge, Economic Organization, and Property Rights is also published by Elgar but not yet available in ebook form. However, Google has cheap ebooks of Nicolai’s Strategy, Economic Organization, and the Knowledge Economy ($40) and Dick’s Firms, Markets, and Economic Change ($60), among other items of interest. And my Capitalist and the Entrepreneur remains available at the best price of all!

Gentle Ben

| Peter Klein |

I don’t think of Ben Bernanke’s approach to monetary policy as soft, passive, or restrained, but of course my optimal monetary policy is no monetary policy. Laurence Ball thinks that Bernanke’s actions after 2008 were surprisingly cautious, compared to what Bernanke advocated as an academic and Fed Governor in the early 2000s.

From 2000 to 2003, when Bernanke was an economics professor and then a Fed Governor (but not yet Chair), he wrote and spoke extensively about monetary policy at the zero bound. He suggested policies for Japan, where interest rates were near zero at the time, and he discussed what the Fed should do if U.S. interest rates fell near zero and further stimulus were needed. In these early writings, Bernanke advocated a number of aggressive policies, including targets for long-term interest rates, depreciation of the currency, an inflation target of 3-4%, and a money-financed fiscal expansion. Yet, since the U.S. hit the zero bound in December 2008, the Bernanke Fed has eschewed the policies that Bernanke once supported and taken more cautious actions — primarily, announcements about future federal funds rates and purchases of long-term Treasury securities (without targets for long-term interest rates).

Ball describes a June 2003 meeting of the Fed’s Open Market Committee at which senior staffer Vincent Reinhart convinced Bernanke that when interest rates are near zero, the right policies are persuading market participants that federal funds rates will continue to fall, selling medium-term bonds and buying longer-term ones (“Operation Twist”), and quantitative easing. When the financial crisis hit, this is exactly what Bernanke did, although — according to Ball — Bernanke had long argued for much more aggressive moves.

Ball argues that Bernanke fell victim to groupthink:

We can interpret the June 2003 FOMC meeting as an example of groupthink. The recommendations in Reinhart’s briefing were presented as the views of a unified Fed staff. In the FOMC discussion, nobody, including Chairman Greenspan, seriously questioned Reinhart’s focus on his three preferred policy options. By the time Bernanke spoke, a consensus had emerged on a number of points, such as opposition to targets for long-term interest rates. Groupthink may have discouraged Bernanke from shaking up the discussion with his past ideas for zero-bound policy.

A reluctance to disagree with the consensus was common at the Greenspan Fed, according to some observers. Cassidy (1996) describes how Alan Blinder, Fed Vice Chair from 1994 to 1996, reacted to FOMC meetings: “The thing that surprised Blinder most was the way decisions were made at the Board. Most of the time, the governors were presented with only one option: the staff recommendation.”

He also suggests that Bernanke, unlike Greenspan, Paulson, Summers, and other key economic policy figures, is shy, withdrawn, and unassertive.

Without intending to, I think Ball makes powerful arguments against conventional monetary policy itself, which relies on a small, secretive, cabal of powerful technocrats, interest-group representatives, and fixers to design and implement rules and procedures that affect the lives of millions, that reward some (commercial and investment bankers, homeowners) and punish others (savers, renters), that shape the course of world events. Do we really want a system in which one person’s personality type has such a huge effect on the global economy?

Against Brainstorming

| Peter Klein |

Brainstorming appears in many strategy, entrepreneurship, and leadership texts, often mentioned in passing with the implication that it’s a great tool for group decision-making. But the research literature suggests a more circumspect attitude. Indeed, this week’s New Yorker features an interesting and informative essay on some of the latest results:

Brainstorming appears in many strategy, entrepreneurship, and leadership texts, often mentioned in passing with the implication that it’s a great tool for group decision-making. But the research literature suggests a more circumspect attitude. Indeed, this week’s New Yorker features an interesting and informative essay on some of the latest results:

The underlying assumption of brainstorming is that if people are scared of saying the wrong thing, they’ll end up saying nothing at all. The appeal of this idea is obvious: it’s always nice to be saturated in positive feedback. Typically, participants leave a brainstorming session proud of their contribution. The whiteboard has been filled with free associations. Brainstorming seems like an ideal technique, a feel-good way to boost productivity. But there is a problem with brainstorming. It doesn’t work.

Writer Jonah Lehrer goes on to quote Keith Sawyer: “Decades of research have consistently shown that brainstorming groups think of far fewer ideas than the same number of people who work alone and later pool their ideas.” Lots more at the source.

Foss at Missouri

| Peter Klein |

O&M co-founder Nicolai Foss will give the 2012 Sherlock Hibbs Distinguished Lecture in Business and Economics Tuesday, 6 March 2012, 10:00-11:30am, in 205 Cornell Hall on the University of Missouri campus. The title is “Open Entrepreneurship: The Role of External Knowledge Sources for the Entrepreneurial Value Chain.” The lecture is sponsored by the Hibbs Professors of the University of Missouri’s Trulaske College of Business and the University of Missouri’s McQuinn Center for Entrepreneurial Leadership (which I direct).

O&M co-founder Nicolai Foss will give the 2012 Sherlock Hibbs Distinguished Lecture in Business and Economics Tuesday, 6 March 2012, 10:00-11:30am, in 205 Cornell Hall on the University of Missouri campus. The title is “Open Entrepreneurship: The Role of External Knowledge Sources for the Entrepreneurial Value Chain.” The lecture is sponsored by the Hibbs Professors of the University of Missouri’s Trulaske College of Business and the University of Missouri’s McQuinn Center for Entrepreneurial Leadership (which I direct).

The full announcement (with Nicolai’s impressive bio) is below the fold. The lecture is free and open to the public, so all are welcome! (more…)

Review of Allen’s Institutional Revolution

| Peter Klein |

I wrote earlier about Doug Allen’s The Institutional Revolution (University of Chicago Press, 2011). Here’s a new EH.Net review by Mark Koyama.

Institutions in Allen’s view minimize transaction costs, where transaction costs include the costs associated with opportunistic behavior. Transaction costs precluded “first-best” institutions from developing in the pre-industrial world. Instead, apparently inefficient institutions such as tax farming, the sale of offices, and the aristocratic dominance of politics persisted for centuries. Allen argues that these apparently inefficient institutions were, in fact, efficient given the existing configuration of transaction costs. This insight, which builds on the ideas of Yoram Barzel, provides a powerful hypothesis for studying institutional change. Allen places particular emphasis on the importance of measurement. In the high variance pre-modern world, measurement was costly or impossible and consequently bureaucrats, soldiers, sailors, and policemen could not be paid on the basis of observable inputs. Alternative institutions had to emerge to deter opportunism and reward effort. These institutions were often elaborate, and sometimes strange; they involved making the bureaucrats, soldiers, or tax collectors residual claimants of some sort. The story of how these institutions disappeared and were replaced by modern institutions is The Institutional Revolution.

The institutional revolution Allen proposes is linked to the industrial revolution because technological change drove institutional change by reducing measurement costs. Standardization reduced variance. This reduction in variance lessened the possibilities for opportunistic behavior and enabled institutions based around the idea of rewarding individuals for their marginal contribution to emerge.

Recent Comments