Author Archive

Kealey and Ricketts on Science as a Contribution Good

| Peter Klein |

Two of my favorite writers on the economic organization of science, Terence Kealey and Martin Ricketts, have produced a recent paper on science as a “contribution good.” A contribution good is like a club good in that it is non-rivalrous but at least partly excludable. Here, the excludability is soft and tacit, resulting not from fixed barriers like membership fees, but from the inherent cognitive difficulty in processing the information. To join the club, one must be able to understand the science. And, as with Mancur Olson’s famous model, consumption is tied to contribution — to make full use of the science, the user must first master the underlying material, which typically involves becoming a scientist, and hence contributing to the science itself.

Kealey and Ricketts provide a formal model of contribution goods and describe some conditions favoring their production. In their approach, the key issue isn’t free-riding, but critical mass (what they call the “visible college,” as distinguished from additional contributions from the “invisible college”).

The paper is in the July 2014 issue of Research Policy and appears to be open-access, at least for the moment.

Modelling science as a contribution good

Terence Kealey, Martin RickettsThe non-rivalness of scientific knowledge has traditionally underpinned its status as a public good. In contrast we model science as a contribution game in which spillovers differentially benefit contributors over non-contributors. This turns the game of science from a prisoner’s dilemma into a game of ‘pure coordination’, and from a ‘public good’ into a ‘contribution good’. It redirects attention from the ‘free riding’ problem to the ‘critical mass’ problem. The ‘contribution good’ specification suggests several areas for further research in the new economics of science and provides a modified analytical framework for approaching public policy.

Video from Coase Conference

| Peter Klein |

Last weekend the Ronald Coase Institute held a conference, “The Next Generation of Discovery: Research and Policy Change Inspired by Ronald Coase.” The impressive lineup featured Kenneth Arrow, Oliver Williamson, Gary Libecap, Sam Peltzman, John Nye, Claude Menard, Ning Wang, Lee and Alexandra Benham, Mary Shirley, and many others. The Institute has now made both days of the program available on video. Great stuff.

O&M in South America

| Peter Klein |

I hope to see O&M readers and friends at next week’s SMS Special Conference in Santiago, “From Local Voids to Local Goods: Can Institutions Promote Competitive Advantage?” The conference focuses on the relationships among institutions, firm strategy, entrepreneurship, and economic growth. Besides the usual paper and paper-development sessions, Tarun Khanna’s keynote and several plenary sessions should be of special interest to O&Mers.

Before heading to Santiago I will be giving talks in Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo sponsored by Mises Brasil, to celebrate a new Portuguese translation of my 2010 book The Capitalist and the Entrepreneur, as well as visiting my friends and colleagues at Insper, which among other activities is starting a doctoral program in business administration.

O&M is popular in Latin America. Nicolai and I are both on the advisory board of CORS and have given the CORS lecture; Nicolai was at USP last month to give a PhD course in strategy and organization.

A Good Reason to Study Corporate Culture

| Peter Klein |

Corporate culture is hard to define and measure (Kreps’s game-theoretic version is probably the one most familiar to economists), but may play a role in explaining variation in firm performance. Of course, one should not invoke “culture” as an explanation for outcomes without specifying some microfoundations. And culture may be as much the result of firm performance as the cause.

But organizations can also serve as a sort of laboratory for understanding the links between informal institutions like culture and more formal institutions such as written rules, policies, and procedures in society at large, a very important issue for economic history, growth, public policy, etc. So say Luigi Guiso, Paola Sapienza, and Luigi Zingales in this short note:

Unlike large societies, however, corporations give hopes to identify the link between culture and formal institutions. . . . First, the creation of a firm is a moment where the founder has the power to set values on a blank slate. Identification of this moment is easier (it is recorded, it is recent) than identifying when and who sets the values of a large community (e.g. a country). Second, culture is easier to change in a corporation. Through hiring and firing corporations can select values by selecting people, avoiding the more difficult strategy of changing their minds. And can punish them if they do not adapt (e.g. by deferring promotion). In large societies only the difficult strategy is available, and slow adaptation is hard to punish, unless slow-adapters are outlawed, which makes culture and law undistinguishable. Third, it is easier to establish the link with performance. Performance is continuously recorded, for the corporation as a whole and often for its segments and divisions in order to implement compensation schemes. Hence, one can study the role of shared norms and beliefs while controlling for the power of economic incentives. Finally, because firms break up and merge much more often than countries, an observer can collect exposure of a firm to a new culture much more often than one can for larger societies.

Here is the link (NBER gated, CEPR, may be ungated for some users).

Review of Organizing Entrepreneurial Judgment

| Peter Klein |

David Howden’s generous review of Organizing Entrepreneurial Judgment appears in the March 2015 issue of the International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal. Excerpt:

David Howden’s generous review of Organizing Entrepreneurial Judgment appears in the March 2015 issue of the International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal. Excerpt:

This ambitious book has a three-fold purpose. First, it seeks to clarify “entrepreneurship” in a manner amenable to both modern management and economics literature. Second, it redefines the theory of the firm in order to integrate the role of the entrepreneur more fully and give a comprehensive view on why firms exist. Finally, and most successfully, it sheds light on the internal organization of the firm, and how entrepreneurship theory can augment our understanding of why firms adopt the hierarchies they do. . . .

Organizing Entrepreneurial Judgment is a massive undertaking, and one that ambitiously spans the unnecessary divide between management studies and economics literature. For the scholar seriously contemplating exploiting this gap further, the book is highly recommended. Having thoroughly enjoyed reading this rendition of their entrepreneurial theory of the firm, it is this reviewer’s hope that Foss and Klein continue to carve out this growing niche straddling the two disciplines. Following up with a more direct and focused primer on their firm would be a welcome contribution to further the growing field.

Also, at last November’s SDAE conference, the book received the 2014 FEE Prize for best book in Austrian economics.

We have several new papers coming out that develop, extend, and defend the judgment-based perspective. Details to follow.

Microeconomics of War

| Peter Klein |

The old Keynesian idea that war is good for the economy is not taken seriously by anyone outside the New York Times op-ed page. But much of the discussion still focuses on macroeconomic effects (on aggregate demand, labor-force mobilization, etc.). The more important effects, as we’ve often discussed on these pages, are microeconomic — namely, resources are reallocated from higher-valued, civilian and commercial uses, to lower-valued, military and governmental uses. There are huge distortions to capital, labor, and product markets, and even technological innovation — often seen as a benefit of wars, hot and cold — is hampered.

A new NBER paper by Zorina Khan looks carefully at the microeconomic effects of the US Civil War and finds substantial resource misallocation. Perhaps the most significant finding relates to entrepreneurial opportunity — individuals who would otherwise create significant economic value through establishing and running firms, developing new products and services, and otherwise improving the quality of life are instead motivated to pursue government military contracts (a point emphasized in the materials linked above). Here is the abstract (I don’t see an ungated version, but please share in the comments if you find one):

The Impact of War on Resource Allocation: ‘Creative Destruction’ and the American Civil War

B. Zorina Khan

NBER Working Paper No. 20944, February 2015What is the effect of wars on industrialization, technology and commercial activity? In economic terms, such events as wars comprise a large exogenous shock to labor and capital markets, aggregate demand, the distribution of expenditures, and the rate and direction of technological innovation. In addition, if private individuals are extremely responsive to changes in incentives, wars can effect substantial changes in the allocation of resources, even within a decentralized structure with little federal control and a low rate of labor participation in the military. This paper examines war-time resource reallocation in terms of occupation, geographical mobility, and the commercialization of inventions during the American Civil War. The empirical evidence shows the war resulted in a significant temporary misallocation of resources, by reducing geographical mobility, and by creating incentives for individuals with high opportunity cost to switch into the market for military technologies, while decreasing financial returns to inventors. However, the end of armed conflict led to a rapid period of catching up, suggesting that the war did not lead to a permanent misallocation of inputs, and did not long inhibit the capacity for future technological progress.

“Robert Bork’s Forgotten Role in the Transaction Cost Revolution”

| Peter Klein |

Thanks to Danny Sokol for passing on this paper by Alan Meese.

Thanks to Danny Sokol for passing on this paper by Alan Meese.

Robert Bork’s Forgotten Role in the Transaction Cost Revolution

Alan J. Meese

Antitrust Law Journal 79, no. 3 (2014)This essay, prepared for a conference examining Robert Bork’s antitrust contributions, examines Bork’s hitherto unknown role in the transaction cost economics (“TCE”) revolution. The essay recounts how, in 1966, Bork helped rediscover Coase’s 1937 article, The Nature of the Firm and employed Coase’s reasoning to explain how various forms of partial integration could reduce transaction costs. As the essay shows, Bork described how exclusive territories, customer restrictions and horizontal minimum price fixing that accompanied otherwise valid integration were voluntary efforts to overcome the costs of relying upon unfettered markets to conduct economic activity. To be sure, Bork did not develop a complete account of TCE capable of informing a full-fledged research program. Nonetheless, Bork did articulate and apply various tools of TCE, tools that reflected departures from the applied price theory tradition of industrial organization.

The essay also offers some brief speculation regarding why scholars have not recognized Bork’s early contributions to TCE. For one thing, Bork did not purport to offer a new economic paradigm. Instead, Bork repeatedly characterized his work as an application of basic price theory, the very economic paradigm that TCE overthrew with respect to the interpretation of non-standard contracts. Moreover, Bork did not persist in his critique of price theory’s once-dominant account of non-standard contracts. After reiterating his views in 1968, for instance, he did not revisit the economics of non-standard agreements for nearly a decade. Finally, when Bork did return to the topic, he deemphasized TCE-based arguments and focused more on the claim that such agreements could not add to the market power already possessed by manufacturers and thus could not produce economic harm. In short, Bork’s failure to reiterate his TCE-based interpretation of non-standard agreements seems partly responsible for the lack of recognition his early contributions have received.

On Bork see also Jack High’s useful 1984 paper, “Bork’s Paradox: Static vs. Dynamic Efficiency in Antitrust Analysis.”

Upcoming Workshops, Seminars, and Events

| Peter Klein |

Some upcoming events of interest to O&M readers:

- “Research and Policy Change Inspired by Ronald Coase,” 27-28 March 2015, Washington DC

- Berkeley-Paris Organizational Economics Workshop, 10-11 April 2015, Paris

- BHC/EBHA Workshop Historical Approaches to Entrepreneurship Theory & Research, 24 June 2015, Miami FL

- TILEC Economic Governance Workshop, “Economic Governance and Social Preferences,” 3-4 September 2015, Tilburg

Benefits of Academic Blogging

| Peter Klein |

I sometimes worry that the blog format is being displaced by Facebook, Twitter, and similar platforms, but Patrick Dunleavy from the LSE Impact of Social Science Blog remains a fan of academic blogs, particularly focused group blogs like, ahem, O&M. Patrick argues that blogging (supported by academic tweeting) is “quick to do in real time”; “communicates bottom-line results and ‘take aways’ in clear language, yet with due regard to methods issues and quality of evidence”; helps “create multi-disciplinary understanding and the joining-up of previously siloed knowledge”; “creates a vastly enlarged foundation for the development of ‘bridging’ academics, with real inter-disciplinary competences”; and “can also support in a novel and stimulating way the traditional role of a university as an agent of ‘local integration’ across multiple disciplines.”

Patrick also usefully distinguishes between solo blogs, collaborative or group blogs (like O&M), and multi-author blogs (professionally edited and produced, purely academic). O&M is partly academic, partly personal, but we have largely the same objectives as those outlined in Patrick’s post.

See also our recent discussion of academics and social media.

(HT: REW)

Two Large-Sample Empirical Papers on Strategy and Organization

| Peter Klein |

Bryan Hong, Lorenz Kueng, and Mu-Jeung Yang have two new NBER papers on strategy and organization using a seven-year panel of about 5,500 Canadian firms. The papers exploit the Workplace and Employee Survey administered annually by Statistics Canada. The data, the authors’ approach, and the results should be very interesting to O&M readers. Here are the links to the NBER versions; there may be ungated versions as well.

Business Strategy and the Management of Firms

NBER Working Paper No. 20846, January 2015Business strategy can be defined as a firm’s plan to generate economic profits based on lower cost, better quality, or new products. The analysis of business strategy is thus at the intersection of market competition and a firm’s efforts to secure persistently superior performance via investments in better management and organization. We empirically analyze the interaction of firms’ business strategies and their managerial practices using a unique, detailed dataset on business strategy, internal firm organization, performance and innovation, which is representative of the entire Canadian economy. Our empirical results show that measures of business strategy are strongly correlated with firm performance, both in the cross-section and over time, and even after controlling for unobserved profit shocks exploiting intermediates utilization. Results are particularly striking for innovation, as firms with some priority in business strategies are significantly more likely to innovate than firms without any strategic priority. Furthermore, our analysis highlights that the relationship between strategy and management is driven by two key organizational trade-offs: employee initiative vs. coordination as well as exploration of novel business opportunities vs. exploitation of existing profit sources.

Estimating Management Practice Complementarity between Decentralization and Performance Pay

NBER Working Paper No. 20845, January 2015The existence of complementarity across management practices has been proposed as one potential explanation for the persistence of firm-level productivity differences. However, thus far no conclusive population-level tests of the complementary joint adoption of management practices have been conducted. Using unique detailed data on internal organization, occupational composition, and firm performance for a nationally representative sample of firms in the Canadian economy, we exploit regional variation in income tax progression as an instrument for the adoption of performance pay. We find systematic evidence for the complementarity of performance pay and decentralization of decision-making from principals to employees. Furthermore, in response to the adoption of performance pay, we find a concentration of decision-making at the level of managerial employees, as opposed to a general movement towards more decentralization throughout the organization. Finally, we find that adoption of performance pay is related to other types of organizational restructuring, such as greater use of outsourcing, Total Quality Management, re-engineering, and a reduction in the number of layers in the hierarchy.

Henry G. Manne (1928-2015)

| Peter Klein |

Very sorry to report the passing of Henry Manne yesterday at the age of 86. Manne made seminal contributions to the literatures in corporate governance, securities regulation, higher education, and many other subjects. Here are past O&M posts on Manne and his contributions. I tried several times to get him to guest blog on O&M but couldn’t pull it off.

Very sorry to report the passing of Henry Manne yesterday at the age of 86. Manne made seminal contributions to the literatures in corporate governance, securities regulation, higher education, and many other subjects. Here are past O&M posts on Manne and his contributions. I tried several times to get him to guest blog on O&M but couldn’t pull it off.

I got to know him fairly well in the last few years and he was a charming companion and correspondent — clever, witty, erudite, and a great social and cultural critic, especially of the strange world of academia, where he plied his trade for five decades but always as a slight outsider.

Here are tributes and commentaries from David Henderson, Jane Shaw, Don Boudreaux, and me. We’ll share more in the coming days.

Team Science and the Creative Genius

| Peter Klein |

We’ve addressed the widely held, but largely mistaken, view of creative artists and entrepreneurs as auteurs, isolated and misunderstood, fighting the establishment and bucking the conventional wisdom. In the more typical case, the creative genius is part of a collaborative team and takes full advantage of the division of labor. After all, is our ability to cooperate through voluntary exchange, in line with comparative advantage, that distinguishes us from the animals.

We’ve addressed the widely held, but largely mistaken, view of creative artists and entrepreneurs as auteurs, isolated and misunderstood, fighting the establishment and bucking the conventional wisdom. In the more typical case, the creative genius is part of a collaborative team and takes full advantage of the division of labor. After all, is our ability to cooperate through voluntary exchange, in line with comparative advantage, that distinguishes us from the animals.

Christian Caryl’s New Yorker review of The Imitation Game makes a similar point about Alan Turing. The film’s portrayal of Turing (played by Benedict Cumberbatch) “conforms to the familiar stereotype of the otherworldly nerd: he’s the kind of guy who doesn’t even understand an invitation to lunch. This places him at odds not only with the other codebreakers in his unit, but also, equally predictably, positions him as a natural rebel.” In fact, Turing was funny and could be quite charming, and got along well with his colleagues and supervisors.

As Caryl points out, these distortions

point to a much broader and deeply regrettable pattern. [Director] Tyldum and [writer] Moore are determined to suggest maximum dramatic tension between their tragic outsider and a blinkered society. (“You will never understand the importance of what I am creating here,” [Turing] wails when Denniston’s minions try to destroy his machine.) But this not only fatally miscasts Turing as a character—it also completely destroys any coherent telling of what he and his colleagues were trying to do.

In reality, Turing was an entirely willing participant in a collective enterprise that featured a host of other outstanding intellects who happily coexisted to extraordinary effect. The actual Denniston, for example, was an experienced cryptanalyst and was among those who, in 1939, debriefed the three Polish experts who had already spent years figuring out how to attack the Enigma, the state-of-the-art cipher machine the German military used for virtually all of their communications. It was their work that provided the template for the machines Turing would later create to revolutionize the British signals intelligence effort. So Turing and his colleagues were encouraged in their work by a military leadership that actually had a pretty sound understanding of cryptological principles and operational security. . . .

The movie version, in short, represents a bizarre departure from the historical record. In fact, Bletchley Park—and not only Turing’s legendary Hut 8—was doing productive work from the very beginning of the war. Within a few years its motley assortment of codebreakers, linguists, stenographers, and communications experts were operating on a near-industrial scale. By the end of the war there were some 9,000 people working on the project, processing thousands of intercepts per day.

The rebel outsider makes for good storytelling, but in most human endeavors, including science, art, and entrepreneurship, it is well-organized groups, not auteurs, who make the biggest breakthroughs.

Top Posts of 2014

| Peter Klein |

It’s been another fine year for O&M, with over 100,000 unique visitors from Albania to Zimbabwe and about every country in-between. Our pageviews are down from 2006, the year we started this blog, but nowadays many people read our posts through Facebook or other syndication and sharing sites, so our actual reach is much larger.

Here are the most viewed posts written in the last year:

- Tirole

- What are “Transaction Costs” Anyway?

- Notes on Inequality

- Gary Becker: A Personal Appreciation

- It’s the Economics that Got Small

- Rich Makadok on Formal Modeling and Firm Strategy

- The Piketty Code

- Gary S. Becker, 1930-2014

- Is Human Capital Theory Compatible with the Strategy Literature?

- Cheating and Public Service

- The Soft Underbelly of Business Model Innovation

- More Skepticism of Behavioral Social Science

- Theories of the Firm

- The Theory of Mind in Agency Theory

- Academics and Social Media

- The New Empirical Economics of Management

Thanks to our readers and commentators for a great 2014. We are looking forward to 2015!

More on Strategy and Game Theory

| Peter Klein |

Recent posts on strategy and game theory (here and here) generated quite a lot of discussion here and on social media. Avinash Dixit offers more grist for the mill in his December 2014 Journal of Economic Literature essay on Lawrence Freedman’s Strategy: A History (Oxford, 2013). (An ungated version is here.) Dixit’s essay contrasts the economist’s and the historian’s view of strategy — “strategy” being game theory for the former, a broader, interpretive, interdisciplinary exercise for the latter — but the discussion is highly relevant for strategic management. The management literature has traditionally taken a wide, flexible view of “strategy,” closer to the historian’s sense than the economist’s, though that is rapidly changing as game theory becomes more widespread in strategic management research and teaching.

Recent posts on strategy and game theory (here and here) generated quite a lot of discussion here and on social media. Avinash Dixit offers more grist for the mill in his December 2014 Journal of Economic Literature essay on Lawrence Freedman’s Strategy: A History (Oxford, 2013). (An ungated version is here.) Dixit’s essay contrasts the economist’s and the historian’s view of strategy — “strategy” being game theory for the former, a broader, interpretive, interdisciplinary exercise for the latter — but the discussion is highly relevant for strategic management. The management literature has traditionally taken a wide, flexible view of “strategy,” closer to the historian’s sense than the economist’s, though that is rapidly changing as game theory becomes more widespread in strategic management research and teaching.

Here’s an excerpt from Dixit’s opening, which gives you the flavor:

[Freedman] heads the preface with a memorable quote from Mike Tyson: “Everyone has a plan till they get punched in the mouth.” Later he quotes another fighter, the legendary German Field Marshal Helmuth Karl Bernhard Graf von Moltke: “no plan survived contact with the enemy” (p. 104). The game theorist will respond: “Those plans are not strategies. They are incomplete. They fail to specify any action at the node of the game tree where you get punched in the mouth or meet the enemy army, or in the ensuing subgame.” It would be extreme stupidity, or arrogance tantamount to stupidity, for a boxer not to recognize the possibility of getting punched in the mouth. And although avoiding battle may be an important aspect of military strategy in many situations (see pp. 47–9), every plan should include a provision for action if or when battle commences. Tyson, or Freedman, will probably counter that even if the boxer starts with a complete plan that specifies the action for this contingency, the punch will make him forget the plan and react hot-headedly. Modern game theorists exposed to behavioral ideas will admit some truth in this, and agree that the boxer’s System 2 calculations are likely to fly out of the ring when the punch lands and System 1 instincts will take over. But they will add that that makes it all the more important for the boxer to strategize better in advance—to take actions before getting punched, either to reduce the risk, or to arrange matters in such a way that the anger and instinct (or the prospects of such reactions) are put to more effective use, as with the strategy of brinkmanship. More generally, “the art of creating power” often entails strategic moves like commitments, threats and promises that game theorists have analyzed following Thomas Schelling (1960). And Freedman’s picture of “strategy as a System 2 process engaged in a tussle with System 1 thinking” (p. 605) looks remarkably like Schelling’s (1984, ch. 3) “intimate contest for self-command.”

I have a twofold purpose in constructing the above exchange. One is to highlight the difference between the perspectives of economists and historians in thinking about the same situation. The second is to argue that each has something to learn from the other, and a fuller understanding can result from their dialog. The two perspectives share a lot of middle ground, and have useful complementarities.

The thoughtful essay is well worth reading in its entirety.

Behavioral Contract Theory

| Peter Klein |

The December 2014 issue of the Journal of Economic Literature contains a nice review article on “Behavioral Contract Theory” by Botond Köszegi. Abstract below, ungated version here.

This review provides a critical survey of psychology-and-economics (“behavioral-economics”) research in contract theory. First, I introduce the theories of individual decision making most frequently used in behavioral contract theory, and formally illustrate some of their implications in contracting settings. Second, I provide a more comprehensive (but informal) survey of the psychology-and-economics work on classical contract-theoretic topics: moral hazard, screening, mechanism design, and incomplete contracts. I also summarize research on a new topic spawned by psychology and economics, exploitative contracting, that studies contracts designed primarily to take advantage of agent mistakes.

On Classifying Academic Research

| Peter Klein |

Should academic work be classified primarily by discipline, or by problem? Within disciplines, do we start with theory versus application, micro versus macro, historical versus contemporary, or something else? Of course, there may be no single “optimal” classification scheme, but how we think about organizing research in our field says something about how we view the nature, contributions, and problems in the field.

There’s a very interesting discussion of this subject in the History of Economics Playground blog, focusing on the evolution of the Journal of Economic Literature codes used by economists (parts 1, 2, and 3). I particularly liked Beatrice Cherrier’s analysis of the AEA’s decision to drop “theory” as a separate category. The Machlup–Hutchison–Rothbard exchange helps establish the context.

[T]he seemingly administrative task of devising new categories threw AEA officials, in particular AER editor Bernard Haley and former AER interim editor Fritz Machlup, into heated debates over the nature and relationships of theoretical and empirical work.

Machlup campaigned for a separate “Abstract Economic Theory” top category. At the time of the revision, he was engaged in methodological work, striving to find a third way between Terence Hutchison’s “ultraempiricism,” and the “extreme a priorism” of his former mentor, Ludwig Von Mises (see Blaug, ch.4). He believed it was possible to differentiate between “fundamental (heuristic) hypotheses, which are not independently testable,” and “specific (factual) assumptions, which are supposed to correspond to observed facts or conditions.” The former was found in Keynes’s General Theory, and the latter in his Treatise on Money, Machlup explained. He thus proposed that empirical analysis be classified independently, under two categories: “Quantitative Research Techniques” and “Social Accounting, Measurements, and Numerical Hypotheses” (e.g., census data, expenditure surveys, input-output matrices, etc.). On the contrary, Haley wanted every category to cover the theoretical and empirical work related to a given subject matter. In his view, separating them was impossible, even meaningless: “Is there any theory that is not abstract? And, for that matter, is there any economic theory worth its salt that is not applied,” he teased Machlup. Also, he wanted to avoid the idea that “class 1 is theory, the rest are applied … How about monetary theory, international trade theory, business cycle theory?” He accordingly designed the top category to encompass price theory, but also statistical demand analysis, as well as “both theoretical and empirical studies of, e.g., the consumption function [and] economic growth models of the Harrod-Domar variety,” among other subjects. He eschewed any “theory” heading, which he replaced with titles such as “Price system; National Income Analysis.” His scheme eventually prevailed, but “theory” was reinstated in the title of the contentious category.

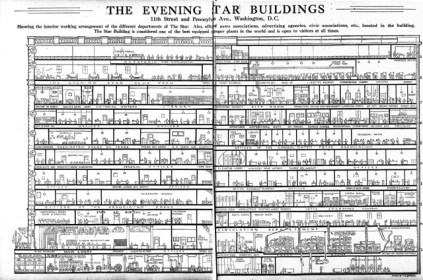

An Information Flow Diagram from 1922

| Peter Klein |

We’ve featured some cool vintage diagrams before, such as the New York and Erie Railroad organizational chart and the diagrams of the Mundaneum. Here’s an information flow diagram from 1922, represented as a cutaway view of the Washington Star newspaper offices. As Jason Kottke notes, it provides “a fascinating view of how information flowed through a newspaper company in the 1920s. Raw materials in the form of electricity, water, telegraph messages, paper, and employees enter the building and finished newspapers leave out the back.”

PhD Strategy Syllabi

| Peter Klein |

Russ Coff has assembled an impressive list of syllabi and reading lists for PhD courses in strategy, innovation, research methods, and related subjects. Feel free to send him additional suggestions. Many useful references here for faculty and students teaching or taking these courses, and for anybody wishing to learn more about classic and contemporary literature in strategic management research.

It’s the Economics that Got Small

| Peter Klein |

Joe Gillis: You’re Norma Desmond. You used to be in silent pictures. You used to be big.

Norma Desmond: I *am* big. It’s the *pictures* that got small.

— Sunset Boulevard (1950)

John List gave the keynote address at this weekend’s Southern Economic Association annual meeting. List is a pioneer in the use by economists of field experiments or randomized controlled trials, and his talk summarized some of his recent work and offered some general reflections on the field. It was a good talk, lively and engaging, and the crowd gave him a very enthusiastic response.

List opened and closed his talk with a well-known quote from Paul Samuelson’s textbook (e.g., this version from the 1985 edition, coauthored with William Nordhaus): “Economists . . . cannot perform the controlled experiments of chemists and biologists because they cannot easily control other important factors.” While professing appropriate respect for the achievements of Samuelson and Nordhaus, List shared the quote mainly to ridicule it. The rise of behavioral and experimental economics over the last few decades — in particular, the recent literature on field experiments or RCTs — shows that economists can and do perform experiments. Moreover, List argues, field experiments are even better than using laboratories, or conventional econometric methods with instrumental variables, propensity score matching, differences-in-differences, etc., because random assignment can do the identification. With a large enough sample, and careful experimental design, the researcher can identify causal relationships by comparing the effects of various interventions on treatment and control groups in the field, in a natural setting, not an artificial or simulated one.

While I enjoyed List’s talk, I became increasingly frustrated as it progressed, and found myself — I can’t believe I’m writing these words — defending Samuelson and Nordhaus. Of course, not only neoclassical economists, but nearly all economists, especially the Austrians, have denied explicitly that economics is an experimental science. “History can neither prove nor disprove any general statement in the manner in which the natural sciences accept or reject a hypothesis on the ground of laboratory experiments,” writes Mises (Human Action, p. 31). “Neither experimental verification nor experimental falsification of a general proposition are possible in this field.” The reason, Mises argues, is that history consists of non-repeatable events. “There are in [the social sciences] no such things as experimentally established facts. All experience in this field is, as must be repeated again and again, historical experience, that is, experience of complex phenomena” (Epistemological Problems of Economics, p. 69). To trace out relationships among such complex phenomena requires deductive theory.

Does experimental economics disprove this contention? Not really. List summarized two strands of his own work. The first deals with school achievement. List and his colleagues have partnered with a suburban Chicago school district to perform a series of randomized controlled trials on teacher and student performance. In one set of experiments, teachers were given various monetary incentives if their students improved their scores on standardized tests. The experiments revealed strong evidence for loss aversion: offering teachers year-end cash bonuses if their students improved had little effect on test scores, but giving teachers cash up front, and making them return it at the end of the year if their students did not improve, had a huge effect. Likewise, giving students $20 before a test, with the understanding that they have to give the money back if they don’t do well, leads to large improvements in test scores. Another set of randomized trials showed that responses to charitable fundraising letters are strongly impacted by the structure of the “ask.”

To be sure, this is interesting stuff, and school achievement and fundraising effectiveness are important social problems. But I found myself asking, again and again, where’s the economics? The proposed mechanisms involve a little psychology, and some basic economic intuition along the lines of “people respond to incentives.” But that’s about it. I couldn’t see anything in these design and execution of these experiments that would require a PhD in economics, or sociology, or psychology, or even a basic college economics course. From the perspective of economic theory, the problems seem pretty trivial. I suspect that Samuelson and Nordhaus had in mind the “big questions” of economics and social science: Is capitalism better than socialism? What causes business cycles? Is there a tradeoff between inflation and unemployment? What is the case for free trade? Should we go back to the gold standard? Why do nations to go war? It’s not clear to me how field experiments can shed light on these kinds of problems. Sure, we can use randomized controlled trials to find out why some people prefer red to blue, or what affects their self-reported happiness, or why we eat junk food instead of vegetables. But do you really need to invest 5-7 years getting a PhD in economics to do this sort of work? Is this the most valuable use of the best and brightest in the field?

My guess is that Samuelson and Nordhaus would reply to List: “We are big. It’s the economics that got small.”

See also: Identification versus Importance

Bottom-up Approaches to Economic Development

| Peter Klein |

Via Michael Strong, a thoughtful review and critique of Western-style economic development programs and their focus on one-size-fits-all, “big idea” approaches. Writing in the New Republic, Michael Hobbs takes on not only Bono and Jeff Sachs and USAID and the usual suspects, but even the randomized-controlled-trials crowd, or “randomistas,” like Duflo and Banerjee. Instead of searching for the big idea, thinking that “once we identify the correct one, we can simply unfurl it on the entire developing world like a picnic blanket,” we should support local, incremental, experimental, attempts to improve social and economic well being — a Hayekian bottom-up approach.

We all understand that every ecosystem, each forest floor or coral reef, is the result of millions of interactions between its constituent parts, a balance of all the aggregated adaptations of plants and animals to their climate and each other. Adding a non-native species, or removing one that has always been there, changes these relationships in ways that are too intertwined and complicated to predict. . . .

[I]nternational development is just such an invasive species. Why Dertu doesn’t have a vaccination clinic, why Kenyan schoolkids can’t read, it’s a combination of culture, politics, history, laws, infrastructure, individuals—all of a society’s component parts, their harmony and their discord, working as one organism. Introducing something foreign into that system—millions in donor cash, dozens of trained personnel and equipment, U.N. Land Rovers—causes it to adapt in ways you can’t predict.

Recent Comments